Murder in Anatolia - Christian missionaries and Turkish ultranationalism

This research has been supported by Erste Stiftung as part of the ESI project on the future of European enlargement. The opinions expressed here are only those of ESI.

See also: ESI Briefing: Turkey's dark side. Party closures, conspiracies and the future of democracy (2 April 2008)

- Dit is de Dag (Radio 1), Matthea Vrij, "Complottheorie over moordzaak christenen" ("Conspiracy to murder Christians") (10 May 2011)

- Süddeutsche Zeitung, Kai Strittmatter, "Unter Mördern" ("Among murderers") (7 April 2011)

- Die Zeit, Michael Thumann, "Meinungsfreiheit nur auf dem Papier" ("Freedom of opinion only on paper") (31 March 2011)

- Der Standard, Manuela Honsig-Erlenburg, "Hinter dem Ganzen steht ein kriminelles Netzwerk" ("There's a criminal network behind it all") (17 March 2011)

- Der Standard, Hans Rauscher, "Türkei: zwei Wahrheiten" ("Turkey: two truths") (12 March 2011)

- Today's Zaman, Orhan Kemal Cengiz, "Ergenekon case through the eyes of Turkey's European friends" (11 March 2011)

- Die Presse, "Nationalismus ist größeres Problem als Islamismus" ("Nationalism is a problem bigger than Islamism") (11 March 2011)

- Zaman France, Pauline Hammé, "L'ombre d'Ergenekon plane sur l'assassinat des chrétiens de Malatya" ("The shadow of Ergenekon hovers over the killing of Christians in Malatya") (3 February 2011)

- Agos, Maral Dink, "Türkiye katilleri korumaya devam edecek mi?" ("Will Turkey continue to protect the murderers?") (21 January 2011)

- Die Tagespost, Regina Einig, "Marionetten in öffentlicher Hand?" ("Puppets in the public authorities' hands?") (19 January 2011)

- Der Tagesspiegel, Thomas Seibert, "Das lange Warten auf Gerechtigkeit" ("Waiting for justice for a long time") (19 January 2011)

- Bugün, "Kafes Eylem Planı'nda yeni gelişme" ("New development in Cage Plan") (18 January 2011)

- Zaman, Şahin Alpay, "Yarın saat 3'te, vurulduğu yerde" ("Tomorrow at 3, at the place where he was shot") (18 January 2011)

- Today's Zaman, "Murder in Anatolia - Christian missionaries and Turkish ultranationalism" (16 January 2011)

- Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, Michael Martens, "Operation Malatya" (16 January 2011)

- Today's Zaman, Orhan Kemal Cengiz, "Murder in Anatolia" (16 January 2011)

- Today's Zaman, "ESI report says Malatya murder telling of Turkish ultranationalism" (15 January 2011)

- Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Michael Martens, "Der Tod in Anatolien" ("Death in Anatolia") (13 January 2011)

- Eurasianet, Yigal Schleifer, "Untangling a Turkish Murder's Wicked Web" (13 January 2011)

The victims (killed 18 April 2007)

Aydin – Geske – Yuksel

Necati Aydin was a Christian convert from Izmir. He moved to Malatya with his wife and two children in November 2003 and became general director of the Christian publishing house Zirve. Since 2005 he had worked as priest of the small Protestant community in Malatya.

Tilmann Geske, a German missionary, worked as a pastor of a Protestant Free church in Germany. In 1997 he moved to Adana (southern Turkey) and in 2002 to Malatya (with his German wife and three children). He taught English, translated, and preached in the local community.

Ugur Yuksel was from an Alevi family in Elazig (a province east of Malatya). He studied in Western Turkey (Izmit), where he came in contact with the local Protestant community and converted. Since 2005 he had worked with Necati Aydin for Zirve Publishing in Malatya.

The main suspects (trial since November 2007)

Gunaydin – Aral

On 18 April 2007 five men raided the office of the Christian publishing house Zirve and killed Necati Aydin, Ugur Yuksel and Tilmann Geske. They were arrested on the spot.

Emre Gunaydin is the alleged leader of the group. He was born in 1988 in Malatya. According to the other suspects, Emre Gunaydin had close relations with the Malatya police and his family had links to well-known ultranationalist organised crime figures.

Salih Gurler, Hamit Ceker and Cuma Ozdemir prepared for the university entrance exam. They met Emre Gunaydin in early 2007 and claim that he intimidated and threatened them to take part in the crime. Abuzer Yildirim met Emre back in 2005. He had worked at the Malatya cotton mill prior to the killing.

Varol Bulent Aral, who described himself as a destitute day labourer, met Emre Gunaydin in fall 2006. Emre testified that Aral told him about the threat of missionary activities and that if Emre did something to stop them "we will guarantee you state support." Aral's personal notebook contained the phone numbers of ultra-nationalist lawyer Kemal Kerincsiz (see below). In October 2010 two witnesses (Orhan Kartal and Erhan Ozen, see below) claimed that Aral organised the crime on behalf of the secret Gendarmerie Intelligence and Counter-terrorism Department (JITEM) and was in contact with JITEM's alleged founder Veli Kucuk (see below).

Key witnesses

Ruhi Abat is an academic at the theology faculty at Malatya University. From 2005 on he undertook research on missionary activities as part of a large team of local academics. He was in close contact with the Malatya gendarmerie: police established that 1,415 phone calls had been made between Ruhi Abat and the gendarmerie in the months prior to the murder.

Metin Dogan is a prison inmate who told the court in 2008 that the head of the Malatya branch of the ultranationalist Ulku Ocaklari (Grey Wolves) organization had offered him money in 2005 to kill "whoever there is at Zirve", the Christian publishing house. A former MHP (Nationalist Action Party) Member of Parliament from Malatya and a member of the military were also allegedly present when the offer was made. Metin Dogan was later imprisoned for murdering his brother's murderer in an unrelated incident and claims that because of this the job of killing the missionaries was transferred to Emre Gunaydin. Dogan also told the court that he knows Emre well from Ulku Ocaklari.

Orhan Kartal joined the Kurdish terrorist organization PKK in 1990. Between October and December 2008 he shared a prison cell with Varol Bulent Aral (see above) in Adiyaman. Aral allegedly told Kartal that he was "a leading power behind the Zirve publishing house incident, that he was in contact with certain state circles, that one of them was JITEM leader Veli Kucuk (see below)."

Erhan Ozen, currently in prison, worked for JITEM between 1997 and 2005. Ozen claimed that the Malatya operation was undertaken by the Gendarmerie Intelligence and Counter-Terrorism Department (JITEM) "to create conditions for a coup". He also told the court that Varol Bulent Aral (see above) played a key role and that it was all coordinated by three retired military, Veli Kucuk, Levent Ersoz and Muzaffer Tekin (see below). Erhan Ozen also testified during the Hrant Dink murder trial in May 2010. There he said he had known about plans to assassinate Dink since 2004.

Veysel Sahin was arrested in Malatya in May 2008 when police found hand grenades and explosives at his house. He is a former informant for the military who later became head of the Malatya office of the Iraqi Turkmen Front (ITF), the main Turkmen political party in Iraq. He claimed that he met Mehmet Ulger (see below), the head of the gendarmerie in Malatya, in March 2006. Ulger wanted to monopolize the distribution of all bibles to have control over who received them and allegedly ordered members of the gendarmerie to threaten the Christian publishing houses. Ulger also allegedly put Sahin into contact with Dogu Perincek (see below), the leader of the ultranationalist Workers' Party who was later arrested as a member of an alleged terrorist network called Ergenekon planning to undermine the government.[1]

Mehmet Ulger was the Malatya Gendarmerie Commander between January 2006 and July 2008. He was incriminated in two anonymous letters. One in summer 2007 claimed that the crime was planned by the gendarmerie and university researcher Ruhi Abat (see above). Ulger confirmed that he had contacts with Abat in 2006. Another detailed letter in 2009 by an alleged (anonymous) Malatya Province Gendarmerie Intelligence officer claimed that Ulger knew about the attack, gave a briefing to the president of the Gendarmerie Headquarters Supervisory Board a few weeks before the murder, "giving detailed reports about the people who were later killed, as well as about their activities", and also removed personally one of the suspect's SIM cards. Ulger was arrested in Ankara on 12 March 2009, interrogated by an Ergenekon prosecutor and then released.

Huseyin Yelki is a Christian convert who was baptized in June 2002. In 2009 he was incriminated by Emre Gunaydin as an instigator of the attack together with Varol Bulent Aral. Emre told prosecutors that "Yelki would help us escape with some money." Then Emre withdrew his statements. The charges were dropped.

Ergenekon suspects with alleged links to Malatya

Levent Ersoz is a retired Brigadier General, and former gendarmerie commander, who was based in Sirnak and Diyarbakir as head of JITEM between 2002 and 2004. He is also a former head of gendarmerie intelligence. A key figure in the Ergenekon investigation, he was arrested in January 2009 and charged with plotting against the government and trying to provoke an armed revolt. Erhan Ozen (see above) refered to him as one of the people preparing an attack in Malatya together with Veli Kucuk and Muzaffer Tekin.

Sener Eruygur is a retired general and former head of the Turkish gendarmerie from August 2002 to August 2004 and as such also responsible for the operations of JITEM, which two witnesses have accused of standing behind the murders. After his retirement he became the president of the ultranationalist Ataturk Thought Association (Ataturkcu Dusunce Dernegi)from 2007 to 2010. He was arrested in 2008 and indicted for planning to stage a military coup in 2003/2004, coordinating efforts with ultranationalist civil society groups and university rectors.

Fatih Hilmioglu was rector of Inonu University in Malatya from 2000 to 2008. Hilmioglu was arrested on 13 April 2009 and charged in the third Ergenekon indictment with helping to prepare the ground for a military takeover under the leadership of the head of the gendarmerie, General Sener Eruygur (see above). Hilmioglu was also a leading member of the hardline Ataturk Thought Association, headed by Sener Eruygur (see above) after 2007. Witness Erhan Ozen (see above) claimed that Hilmioglu supported monitoring of the missionaries in Malatya by university staff and that he was in contact with Muzaffer Tekin (see below), the retired captain of the Turkish Armed Forces and Ergenekon suspect.

Muzaffer Tekin is a retired Captain of the Turkish Armed Forces and member of the ultranationalist Worker's Party of Dogu Perincek (see below). He was arrested in the first wave of Ergenekon arrests because of his close link to Oktay Yildirim, who had hidden grenades in a house in Umraniye (Istanbul). Both Yildirim and Tekin were indicted, among other things, for instigating the attack on the Ankara Council of State where one judge was killed in 2006. Witness Erhan Ozen (see above) claimed in October 2010 that Tekin also planned activities targeting minorities and that he often came to Malatya.

Veli Kucuk is a retired gendarmerie general and according to another indictment issued in 2008 one of the founders of JITEM. Kucuk participated in many anti-Christian demonstrations, including demonstrations against the Ecumenical Patriarchate and Hrant Dink, between 2005 and 2006. He was arrested on 22 January 2008 as part of the Ergenekon investigation and is currently standing trial in Istanbul. He has long been associated with ultranationalist circles in Turkey. Witness Ozen (see above) claimed that he had a leading role in planning the Malatya murders.

Turkey's anti-Christian campaign (2001-2009)

Sinan Aygun is the chairperson of the Ankara Chamber of Commerce. He is an outspoken opponent of the government, the EU and the work of Christian missionaries, about which the chamber issued a special report. Aygun was arrested in July 2008 and charged with being part of a conspiracy to overthrow the government. Police found 2.5 million Euro in his house. The money was allegedly planned to be used to finance activities by the Ergenekon network. Aygun was in contact with Veli Kucuk (see above), the retired gendarmerie general and allegedly one of the founders of JITEM. He regularly visited leading generals, including the head of the gendarmerie, Sener Eruygur (see above).

Sevgi Erenerol is the spokesperson of the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate, an institution with a long history of ultra-nationalist activism which is not recognised by any other church. The "church" run by her family and without congregation was always intensely hostile towards all other Christians, including the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate. In recent years the Turkish Orthodox church became a meeting place for many ultranationalists who were later charged with being part of the Ergenekon terrorist network. Together with Ergun Poyraz (see below) Sevgi Erenerol set up the ultra-nationalist Ayasofya Dernegi (Hagia Sophia Association) in October 2006. She spoke often at conferences warning that "missionary activities in Turkey are aiming at more than religious goals." Erenerol also briefed senior military about the "missionary threat" in 2006. She was arrested in January 2008 as a member of the alleged Ergenekon network.

Kemal Kerincsiz was Ergun Poyraz' lawyer and head of the ultranationalist Great Union of Jurists (Buyuk Hukukcular Birligi) since its foundation in April 2006. He instigated most Article 301 Penal Code trials for denigrating Turkishness, filing charges against Orhan Pamuk (Nobel Prize laureate 2006), writer Elif Safak, Hrant Dink and others. He also organized demonstrations against the Ecumenical Patriarchate and Turkish Armenians together with others accused of forming the Ergenekon network: Veli Kucuk, Muzaffer Tekin and Sevgi Erenerol (all: see above). He also led the legal campaign against two Turkish Protestant converts, who were arrested in October 2006, charged with slandering Turkishness and then stood trial for almost four years. Kerincsiz was arrested in January 2008 and charged with being part of the Ergenekon terror network.

Tuncer Kilinc is a retired general. He was the Secretary General of the National Security Council (NSC) from August 2001 until 2003. In 2001 a report prepared for the NSC warned that the real goal of missionary activities was the "division of Turkey". Kilinc made the same claim many times in public. In a speech in 2002 he accused the EU of being "a Christian Club, a neo-colonialist force, determined to divide Turkey." He also attended meetings in the Turkish Orthodox Church. Sevgi Erenerol (see above) also visited Kilinc in Ankara. In January 2009 he was charged in the third Ergenekon indictment with maintaining links to members of Ergenekon and providing confidential documents to Ergun Poyraz, the author (see below).

Ergun Poyraz is an ultranationalist writer who published "Six Months among the Missionaries" in 2001. An anti-Christian, anti-AKP and anti-EU bestselling author, he was arrested in 2007 for his links to the alleged Ergenekon network accused of plotting to undermine the government. Many confidential military documents were found in his house. During a search of the Workers' Party office in Izmir a document was found indicating that he was also paid by JITEM.

The lawyers of the victims' families

Cengiz – Dogan

A whole team of distinguished human rights lawyers has been following the Malatya court case on behalf of the victims' families. Two of the most visible and outspoken are Orhan Kemal Cengiz and Erdal Dogan. Cengiz, who is based in Ankara, is the legal advisor of the Protestant Association, a columnist and one of the founders of Amnesty International in Turkey. In 2003, he set up the Human Rights Agenda Association (HRAA). Erdal Dogan, an Istanbul-based lawyer, had defended Hrant Dink and his family over many years. Other laywers include Sezgin Tanrikulu who came from Diyarbakir, where he had defended Kurdish victims of human rights abuses, Hafize Cobanoglu from Izmir, Ergin Cinmen and Fethiye Cetin, who represented the Dink family in the Hrant Dink murder trial.

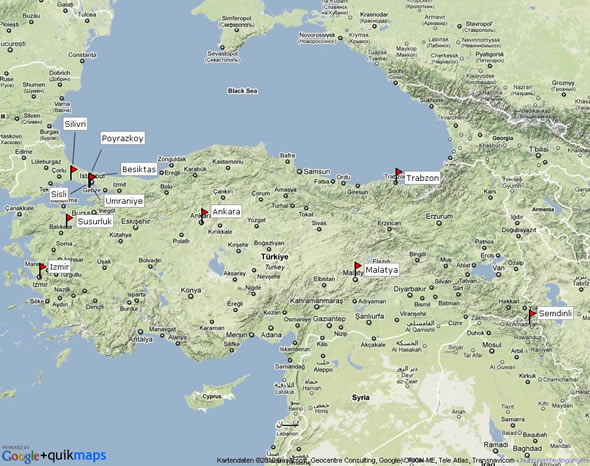

Ankara (murder of Council of State judge, May 2006)

Istanbul – Besiktas (trial of Hrant Dink murder case since 2 July 2007)

Istanbul – Poyrazkoy (weapons found in April 2009, linked to Cage Plan indictment)

Istanbul – Sisli (murder of Hrant Dink outside his office, 19 January 2007)

Istanbul – Umraniye (weapons found in June 2007, beginning of Ergenekon investigation)

Izmir (home of victim Necati Aydin)

Malatya (murder of missionaries, April 2007)

Semdinli (killing of civilians in operation by gendarmerie intelligence unit members, November 2005)

Silivri (different trials related to alleged Ergenekon network and coup allegations since October 2008)

Susurluk (car crash in November 1996, revealing close links between state security institutions and organised crime in Turkey)

Trabzon (murder of Catholic priest Andrea Santoro, February 2006; home of the murderer of Hrant Dink)

In April 2007 a gruesome triple murder took place in the Central Anatolian city of Malatya. The victims, tortured, stabbed and strangled, were two Turks and one German. All three were Protestant Christian missionaries who had recently moved to Malatya. Five young men, armed with knives and covered in blood, were found at the scene of the crime only moments after it happened.

What made the Malatya killings different from an ordinary murder case was the suspicion, present from the outset, that this was not an isolated attack by a group of nationalist youngsters. As the investigation unfolded, serious questions began to emerge, which have not yet been answered. Were anti-government elements of the Turkish state – or, more specifically, secret networks within the Turkish gendarmerie and ultranationalists linked to them – involved? Was the murder of missionaries in Malatya an operation by Turkey's so-called "deep state" to destabilise an elected government by targeting Christian "enemies" of the Turkish nation?[2]

This has certainly been the impression of the team of lawyers, a who-is-who of Turkey's most prominent human rights defenders, who have been representing the families of the victims in the Malatya trial that began in November 2007. From the very beginning these lawyers have drawn attention to the anti-Christian and anti-missionary campaigns in Turkey that were supported by a number of ultranationalist associations and writers and which had gained intensity in the period leading up to the Malatya murder. They also underlined that the murdered Christians had in fact been under permanent close observation by the gendarmerie and that the main murder suspect, Emre Gunaydin, had close contacts with the police. They pointed out that the gendarmerie was monitoring missionary activity in close cooperation with academics at Malatya University, whose rector was an outspoken ultranationalist, regularly meeting with leaders of the Turkish military.

As the Malatya trial unfolded, many more links have emerged between the Malatya murders and ultra-nationalists elsewhere in Turkey who have since been arrested for plotting to overthrow the government, for which, prosecutors have argued, they had formed a terrorist network called Ergenekon.[3] Witnesses in Malatya explicitly linked the murders of the missionaries to an infamous institution much discussed in Turkey in the 1990s as being responsible for a series of mysterious assassinations, the secret Gendarmerie Intelligence and Counter-terrorism Department (Jandarma Istihbarat ve Terorle Mucadele, or JITEM) together with one of its alleged founders, a Turkish ultranationalist and retired gendarmerie general, Veli Kucuk. Kucuk himself played a leading role in anti-Christian campaigns in Istanbul which preceded the assassination of Turkish Armenian journalist Hrant Dink.[4] Both in Malatya and in Istanbul the local branches of the ultranationalist Grey Wolf youth organisation (Ulku Ocaklari) had also organised demonstrations against Christians. In 2008 both Veli Kucuk and Levent Temiz, the head of the Istanbul branch of the Ulku Ocaklari, who had personally threatened journalist Hrant Dink, were arrested and put on trial, charged with being members of Ergenekon.

The lawyers representing the Malatya victims' families have also pointed to similarities between different attacks on Christians in 2006 and 2007. Hrant Dink was killed in Istanbul in early 2007, shortly before the Malatya murders, by another young ultranationalist, who had in fact been under permanent observation by the gendarmerie and police. The alleged instigator in the Hrant Dink murder case, Yasin Hayal, who is currently on trial, had numerous links to the gendarmerie. Yasin Hayal paid regular visits to the Trabzon branch of the gendarmerie intelligence department, whose branch director supposedly described Hayal as "a solid boy, a clean one, [who] will do good work in the future."[5] This notwithstanding the fact that in 2002 Yasin Hayal had beaten the Catholic priest in the Santa Maria Church in Trabzon so badly that the priest was in coma for days (in 2006 the successor priest in Santa Maria Church, Italian Andrea Santoro, was killed by another ultranationalist youth). In addition Hayal's brother-in-law had been a gendarmerie informant who warned his superiors in the gendarmerie in Trabzon in 2006 that Hrant Dink would be murdered.[6]

The lawyers representing the Malatya victims' families argued in a long letter to the court in April 2010 for the missionary murder case to be merged with one of the Ergenekon trials. They also pointed to the Cage Operation Action Plan ("Kafes Operasyonu Eylem Plani"), an alleged plot prepared by parts of the Turkish military to intimidate and assassinate non-Muslims in Turkey in order to create an atmosphere of chaos. The plan was made public in 2009. The first sentence of the plan refers to the killings of Priest Santoro (in Trabzon in 2006), the murder of Hrant Dink (in 2007) and the Malatya murders as "operations".[7] The judges in Malatya have not yet made a decision on this request by the lawyers.

So far 30 court hearings have taken place in the Malatya trial. At the most recent hearing in December 2010 a new defence lawyer representing the suspects once again accused the murdered Christians of "planning to eliminate our religion, dividing up our country, bribing our people and financially supporting terror organisations." He also tried to intimidate the judges, shouting that "this is a Protestant court."[8] The next hearing will take place on 20 January 2011. Considering the seriousness of the charges, it is striking how little attention has been paid to the Malatya trial in recent months in Turkish and international media. For anybody who is genuinely interested in understanding contemporary Turkish politics, and the spectacular court cases which currently look into the dark world of ultranationalist associations and their links to different parts of the state, the Malatya murder trial is a very good place to start.

The year 2006 witnessed a series of seemingly random attacks against Christians throughout Turkey. On 8 January Kamil Kiroglu, a Protestant church leader in Adana, was beaten by five young men.[9] On 5 February Andrea Santoro, an Italian Catholic priest, was shot dead in the Santa Maria church in the Black Sea city of Trabzon by a 16 year old boy shouting "God is Great" (Allah-u-akbar).[10] A few days later a Catholic friar was attacked in Izmir by a group of young men who had threatened to kill him.[11] On 12 March Henri Leylek, a Capuchin priest, was attacked in the Mediterranean city of Mersin.[12] On 2 July Pierre Bruinessen, a Catholic priest, was stabbed in Samsun.[13] In December the priest of the Tepebasi church in Eskisehir was attacked.[14]

It appeared that a sudden wave of extreme anti-Christian sentiment had appeared as if from nowhere to grip the country – all the more striking as it erupted just a few months after Turkey finally succeeded in opening accession talks with the European Union in October 2005. Turkey's small Christian community lived in growing fear. "We are no longer safe here," said the then Vicar Apostolic for Anatolia, Luigi Padovese.[15] In November 2006 the Minority Rights Group, an NGO, warned that "Christians have borne the brunt of rising religious intolerance."[16] Felix Korner, a German Jesuit whom the Vatican had sent to Ankara to encourage a Christian-Islamic dialogue, noted that the "basic level of anti-Christian sentiment has increased."[17]

For some observers, in Turkey as well as abroad, this wave of violence was a reflection of a rise in violent Islamism. This fear was reinforced by another shocking incident. On 17 May 2006, a lawyer, Alparslan Arslan[18], stormed into the Council of State (Danistay, Turkey's highest administrative court) in Ankara shouting "I am God's soldier, God is great!"[19] Arslan shot at judges sitting in their chamber, killing one of them.[20] Arslan later stated that he was motivated by a court ruling from February 2006 when the judges had decided not to promote a primary school teacher because she wore a headscarf outside class.[21] On the day of the judge's funeral in Ankara on 18 May 2006, tens of thousands of people demonstrated against the AKP government which they accused of abetting such attacks. The presiding judges of the most important courts (Constitutional, Council of State, Court of Appeals), joined by the president of Turkey's Bar Association and state prosecutors, demonstrated at Ataturk's mausoleum. Thousands joined the demonstrations, chanting "Turkey won't become Iran, the murderer is the government" and "Turkey is secular and will stay so."[22] "A bullet for secularism", ran the headline in Milliyet, a Turkish daily.[23] In September 2006, Der Spiegel asserted that "a deep chasm is opening up in Turkish society" between a secular and modern upper class on the one hand and "fanatical masses" on the other. Often, the author noted, "one spark is enough to set the fanatical fire alight."[24]

In 2007, things went from bad to worse. On 19 January Hrant Dink, founder and editor-in-chief of the weekly Agos and one of the advocates of Turkish-Armenian rapprochement, was assassinated in front of his office in Istanbul's Sisli district. His murderer, like that of Father Andrea Santoro, was a 16 year old young man from the Black Sea town of Trabzon.[25] Then another gruesome attack on Christians took place in April 2007 in the Central Anatolian city of Malatya.[26]

On 18 April at around 12.30 pm Gokhan Talas, a graphic designer, arrived with his wife at the office of Zirve, a Christian publishing house in Malatya, which he shared with Necati Aydin, a Turkish priest, and Ugur Yuksel, both Turkish converts to Christianity. Trying to enter the premises, Talas and his wife found the door locked from the inside. They became suspicious and called the police. Having arrived on the scene, police officers entered the office to find three men – Necati Aydin, Ugur Yuksel and Tilmann Ekkehart Geske, a German missionary – in a pool of blood, covered with stab wounds, their throats slit, their hands and feet bound with rope. Geske and Aydin were declared dead at the scene of the crime. Yuksel died shortly after reaching the hospital.

The police did not have to look far for suspects. Three young men, Hamit Ceker, Salih Gurler, and Cuma Ozdemir, were apprehended on the spot, covered with blood. Abuzer Yildirim was found on a balcony one floor below as he tried to escape. A fifth man, Emre Gunaydin, had fallen from the third floor and was lying, injured, on the pavement in front of the building.[27] Emre Gunaydin turned out to be the alleged leader of the group. All suspects were between 19 and 20 years old.

The Malatya murders shocked the entire nation. Was this another terrifying case of religious-inspired fanaticism? At first glance it seems so.[28] British expert on Turkey Gareth Jenkins, writing in 2009, described the Malatya case as the "brutal murder of three Christian missionaries by Islamist youths."[29] An American documentary about the murders reported that Emre Gunaydin told Necati Aydin during the fatal encounter to repeat that "there is no God but Allah." When Aydin defended his Christian belief, according to the film, "the violence exploded."[30] The five suspects had left identical notes, which they apparently wrote upon Emre Gunaydin's suggestion:[31]

"We are brothers. We go to death, we might not return. If we die, we will become martyrs, those that stay alive should help each other. Give us your blessings. We five are brothers, we are going to death, we might not return."[32]

Back in 1999 Turkey had obtained official candidate status from the European Union in return for a commitment to carry out human rights reforms, among other things. This also meant taking steps to improve the legal situation of many of Turkey's minorities, including its tiny Christian community (less than 150,000 in a population of 72 million people), as well as giving cultural rights to Kurds and reining in the power of Turkey's all-powerful armed forces.

Turkey's minorities have long been perceived by the state, including the military establishment, as a potential threat to national unity. The National Security Policy Document (NSPD or Milli Guvenlik Siyaseti Belgesi) is a secret document drafted by Turkey's National Security Council.[33] Throughout the years, every edition of the NSPD has featured a list of internal and external enemies of the Turkish state. These have included Armenians and Greeks, traditional sources of trouble and suspicion; Kurds, seen as a separatist threat since the beginning of the Republic; leftists and communists, particularly during the Cold War; and, after the fall of communism, Islamists and religious "reactionaries". All these internal enemies were said to be even more dangerous because of their external supporters: the Turkish Greek citizens found them allegedly in Greece; the Armenians in their diaspora; Kurds in neighbouring countries; communists in the Soviet Union; and Islamists in Iran. It was only in the National Security Policy Document's most recent revision, which was adopted in November 2010 and drawn up by the government itself, that most internal enemies were removed from the list.[34]

For decades, Turkey's Protestants were not seen as a serious threat by the National Security Council. Their number is tiny: some 3,000 out of a total population of 72 million people in Turkey. There are many more Buddhists in Austria (some 10,400 out of a total population of 8 million) than Protestant Christians in Turkey.[35] Nor has Turkey ever been easy terrain for missionaries. Statistics by Jehova's Witnesses give the following numbers of baptisms in 2008: 643 in Greece, more than 3,600 in Germany, more than 6,000 in Ukraine but only 91 in Turkey. A few dozen missionaries among some 3,000 Protestants did not appear to be a priority concern for Turkey's national security establishment – that is, until 2001.

In 2001, Turkish author Ergun Poyraz published Six Months among the Missionaries ("Misyonerler Arasinda 6 ay"), an exposé of a web of connections between Turkey's alleged enemies. According to Poyraz, missionaries were a genuine threat to his country, all the more so since they enjoyed the backing of a dangerous outside power: the European Union. For Poyraz, the reforms demanded by the EU were in themselves cause for alarm. The first sentence of Poyraz's book is clear: "In this book I take into account the desire of Christian and Jewish missionaries to get their hands on the lands of our country … in an unarmed crusade."[36] Theirs is a crusade using "books, schools, hospitals, movies, and all sorts of propaganda methods. A big missionary army has invaded our country."[37] It is important to note that in Turkey missionary activity is legal.

Since the 1990s, Poyraz has published books on subjects that reflect the concerns of Turkey's national security establishment.[38] In 1998 his book Refah's Real Face was used during a trial against the Refah (Welfare) Party, which ended in the party's closure.[39] In 2007, on the eve of another closure case – this time, against the governing AKP – he wrote Children of Moses: Tayyip and Emine ("Musa'nin Cocuklari: Tayyip ve Emine"), a bestseller about Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan and the supposed threat to Turkey posed by his party (and his wife, Emine, who is wearing a headscarf).[40] Poyraz accused Erdogan and his conservative allies of being crypto-Jews with secret ties to the conspiratorial forces of "global Zionism."[41]

In his 2001 book on missionaries, Poyraz spins a familiar nationalist tale: how Western missionaries instigated the Ottoman Armenians to rise up against the Turks during World War I; how later, in the 1980s, Christian missionaries again "reached out to the Kurds and instigated them to rebel."[42] As to what now made the missionaries so dangerous, Poyraz is explicit: "the most important reason why the missionaries have been given limitless freedom in their activities is the European Union."[43] He adds, "As you know, the West has not digested that the Turks conquered Istanbul and eliminated Byzantium, because Istanbul and Anatolia are holy lands for Christians."[44] In the 1920s, Poyraz notes, Turkey was led by Ataturk and was able to defend itself against the Western powers' plans to split up Turkey through the Treaty of Sevres.[45] Today, warns Poyraz, Turks must get ready for a new anti-colonial battle. He concludes his book with a threat,

"I think it is useful to remind the missionaries of the following: This land has been Turkish for thousands of years. Its price was paid with blood. Those dreaming of getting back these lands should foresee paying that price."[46]

Poyraz's analysis was picked up in 2001 by the National Security Council (NSC), at the time widely considered the most powerful institution in Turkey. The NSC's Secretary General was General Tuncer Kilinc, one of the most outspoken opponents of Turkey's EU aspirations, who repeatedly and publicly accused the EU of working on dividing Turkey and supporting Kurdish terrorists to this end. In December 2001 an article in the daily Sabah, under the title "Missionary Alarm", refered to a special report prepared for a meeting of the National Security Council:

"Missionary activities were put on the December meeting agenda of the National Security Council. A report prepared for the NSC warned that the real goal of missionary activities was not religious propaganda, but the ‘division of Turkey'. [The report] emphasised that legal measures were not adequate to prevent such activities."[47]

The report submitted to the National Security Council alleged that 8 million bibles had been distributed for free in Turkey during the previous three years. It highlighted in particular the dangerous role played by Christian publishing houses and their links to the terrorist PKK. "Although these publishing houses have published separatist maps of Turkey, nothing has been done against them," the report alleged. "During the last year alone, 19 churches have been opened in Istanbul."[48] Tuncer Kilinc, the NSC's Secretary General, warned in a public speech in 2002 that the EU was "a Christian Club, a neo-colonialist force, determined to divide Turkey."[49]

In December 2004 Turkey received a date for the launch of EU accession negotiations in one year's time. Strikingly, this coincided with an ever more aggressive campaign against Christian missionaries. In 2004 Poyraz's book was reprinted by a nationalist publishing house.[50] The same year, the Ankara Chamber of Commerce issued its own report on missionaries.[51] Sinan Aygun, who has led the Ankara Chamber since 1998, publicly warned that the reforms promoted by the EU were helping missionary activities. As Aygun explained on the Chamber's website:

"At this moment, Turkey is under attack by missionaries. In the capital, Ankara, they can be found in every corner. They are gaining sympathisers through social events such as picnics and house visits, as well as educational activities such as religious services, winter schools, seminars and conferences … They use religion as a weapon. What else do they need? There is a famous African saying: ‘When the Christians arrived in Africa, the Africans had their land and the Christians had their bible. The Christians told us to pray with our eyes closed. When we opened our eyes, they had our land and we had their bible.' Let us be careful about not experiencing a similar situation in Turkey."[52]

The Chamber's report is full of surprisingly specific details. It notes, for example, that 15 people joined the Ankara Kurtulus Church in 2003, bringing the overall size of the flock to 130.[53]

Then Ilker Cinar, a Turkish convert who had been working as a Protestant missionary in Turkey for over ten years, added his voice to this chorus. In 2005 Cinar turned his back on Christianity and, after stating publicly how wonderful it felt to return to the Muslim faith, he explained on television the true intentions of Turkey's Protestants: the Christians wanted "to re-conquer the holy land" and to work with the Kurdish PKK.[54] In 2005 he published a book with the title "I was a missionary, the code is decoded – former Bishop Ilker Cinar reports" (Ben bir misyonerdim, sifre cozuldu – Eski Baspapaz Ilker Cinar anlatiyor). There he describes how missionaries are trying to destroy Turkey.

In 2007, the author Ergun Poyraz was arrested due to alleged close links to a group of ultranationalists who had been hiding grenades in Istanbul and whom prosecutors charged with having murdered a judge in Ankara in 2006, a false flag operation that was supposed to look like an Islamist crime (see page 4). When Poyraz was captured, the police found many confidential military documents in his home containing information which he used for his books.[55] According to original documents included in the Ergenekon indictment, he had also been receiving money from JITEM, the secret Gendarmery Intelligence and Anti-Terror Organisation.[56] Sinan Aygun, the head of the Ankara Chamber of Commerce, was also arrested. He had been in close contact with key Ergenekon suspects[57], including general Sener Eruygur, the head of the gendarmerie who allegedly planned to carry out a military coup in 2003-2004.[58] Police found 2.5 million Euro in cash in Aygun's house, which prosecutors claim would have been used to finance activities by this ultranationalist network.[59]

Tuncer Kilinc, the anti-European former general secretary of the National Security Council, was also arrested in 2008 and indicted for being a member of the same conspiratorial network. Prosecutors found that he had also attended numerous meetings with other alleged anti-government and anti-Christian conspirators in the Istanbul Turkish Orthodox Church, where many of the crimes were allegedly discussed. Members of that very group had played a prominent role in the hate-campaign against Christians and in particular against Armenian journalist Hrant Dink.[60]

Finally, it emerged in 2008 that Ilker Cinar had not in fact ever been a genuine convert. He had been on the payroll of the Turkish military since 1992, even while posing as a Protestant pastor and infiltrating Turkey's small Protestant community.[61] In fact, as became clear during the Malatya trials, the intense interest of parts of the state, in particular the gendarmerie, in the activities of Christian missionaries had turned this small group into one of the most closely watched groups in the country.

Malatya is one of the oldest cities in Anatolia, dating back to Hittite days (1180 – 800 B.C). It lies on a fertile plain by a tributary of the Euphrates, at the foot of the Taurus mountain range.[62]The region is famous for apricots, producing 95 percent of Turkey's dried apricots (Turkey is the world's leading apricot producer). The town has a population of roughly 400,000 people.

Old Malatya has several historic landmarks. One of them is a Seljuk Mosque (Ulu Camii) built on an earlier Arab foundation. Another is a 13th century caravanserai. The town also has a long Christian heritage. "Until the 1900s there were 33 Armenian churches in the province of which 10 were in the city centre," one resident recently recalled.[63] There were also many Armenian schools.[64] After World War I and the deportations and killings of Armenians there were almost no Christians left in Malatya. The few who remained moved to Istanbul in the 1960s. One of them was Hrant Dink who was born in Malatya in 1954. In the period when Dink moved with his parents to Istanbul in 1961, Christian life in Malatya came to an end.

This changed in 2002 when a small group of foreign missionaries arrived in Malatya, setting up two Protestant publishing houses, Kayra and Zirve. Tilmann Geske, a German, moved to Malatya in 2002 with his wife and three children. Geske had studied theology in Germany. He came from Lindau, an idyllic city on Lake Constance, where he divided his time between a job at a warehouse and his duties as a pastor at "New Life", a Protestant Free church. It was at the church that Tilmann met his wife Susanne, who had studied for three years at a Bible school in Switzerland. She later recalled that she put up several conditions when Tilmann proposed to her:

"You want to marry me? Ok. A potential husband has to fulfil three criteria. First he has to be a Christian. Second he must have been a Christian for longer than I have. And third, I want to live in a Muslim country."[65]

Tilmann accepted. Before going abroad as missionaries, he and his wife took courses in the UK and Germany. Tilmann trained as a certified English teacher. In 1997 the young family moved to Adana, where Tilmann registered a translation office called "Silk Road". The Geskes learned Turkish. As Susanne Geske later explained, their ambition was to "reach the unreachable, to go further East, to the Turkish Islamic heartland."[66] When they moved with their children to Malatya in 2002 Susanne called it a "bigger challenge."[67] Even before the Geskes' arrival, the couple received front-page coverage in the local press. A South African missionary who had arrived in Malatya earlier in 2002 to run the Kayra Christian publishing house in Malatya told them:

"Congratulations! You made it onto the cover page of a local newspaper … In this way one learns that Christians are dangerous and are coming to Malatya."[68]

In Malatya Tilmann taught English, translated, and preached to a Protestant community of about 15-20 adults.[69]

Necati Aydin was a Christian convert from Izmir. He moved to Malatya with his wife and their two children in November 2003, becoming general director of the Zirve publishing house (which also has offices in Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir and Van). Necati converted after falling in love with Semse, an Orthodox Christian from Antakya (the ancient Antiochia) who herself had converted to Protestantism. German missionary Wolfgang Hade, who was married to Semse's sister, later recalled Semse's reaction when Necati initially expressed doubts about converting: "She said: ‘It is over! I talked to Necati on the phone and he told me that he wanted to remain a Muslim. If God does not bring him back, then the story is over.'"[70]

The couple married in 1997. A year later Necati began to lead a community of converts in Izmir. The group, whose meetings took place in the two lower floors of an apartment building, had problems with the authorities. On one Sunday morning in September 1999, most of the Christians were arrested by the police. They were released the same evening. On 1 March 2000 Necati and another colleague were arrested by the gendarmerie after distributing bibles and Christian literature in a small town near Izmir. When the case went to trial, the witnesses called by the prosecution all withdrew their previous testimonies, admitting that "people from the gendarmerie had urged them to make false statements" against Necati and his colleague. The pair was released after spending 30 days in prison.[71]

Things did not change after Necati arrived in Malatya. Here too, he was repeatedly stopped by the gendarmerie while distributing Christian literature in the countryside. The local media launched a hate campaign against Christians. In February 2005, the local newspaper Bakis alleged that there were 48 "home churches" in "every part of the city."[72] On 19 February 2005 the head of the Kayra publishing house issued a public statement: "There is open agitation against Christians and foreigners in Malatya. Despite the fact that there is no evidence that Christians living in Turkey are promoting [Kurdish] separatism, there is no end to these accusations."[73]

On 5 December 2005 a group of young ultra-nationalists demonstrated in front of the offices of a transport company that had delivered a shipment of bibles to Kayra. One daily reported that Burhan Coskun, the head of the Malatya chapter of Ulku Ocaklari – a nationalist youth organization commonly refered to as Grey Wolves – participated in the demonstration. "Do we live in England?" he was said to have yelled.[74] Local newspapers chimed in. "Now it is the turn of the Vatican representation" ran one of the headlines, alluding to the attempt by Mehmet Ali Agca, himself a native of Malatya province close to the Grey Wolves, to kill Pope John Paul II in 1981.[75] The Kayra office closed in 2005. [76]

The third victim, Ugur Yuksel, moved to Malatya in 2005. Ugur came from an Alevi family in Elazig province, which is close to Malatya. He studied engineering in Western Turkey where he converted to Christianity. After financial problems forced him to give up his studies, he moved back home, where he tried to earn money by running a phone shop. For almost a year he was "the only Christian in the region, with no Christian community, not even a group of Christians who prayed or read the bible together."[77] Ugur moved to Malatya, where he found a job at the Zirve publishing house. Wolfgang Hade described his sorrows:

"For a long time he has been planning to marry. But there are repeated obstacles: finances, religion, and parents' approval. Necati and Semse sometimes told him jestingly, ‘You will get married in heaven.'"[78]

Emre Gunaydin, the alleged leader of the group charged with the murders, was born in 1988 in Malatya. He lived with his father Mustafa, who worked as a technician at Malatya University. Mustafa Gunaydin also owned a martial arts centre. The father later told the court,

"I am known in Malatya for having ulkucu [ultra-nationalist] views. But this is based on my thinking during my youth. Now I am not linked with anyone."[79]

Emre finished school in 2006. He wanted to become a lawyer. Having twice failed the very competitive university entrance exam, Emre persuaded his father to find him a place at a private dormitory for students from outside Malatya. It would help him prepare for his third attempt, he explained.[80] According to Mustafa Gunaydin, his son said that

"There were students with good grades in the dormitory. If he studied with them that would be useful. That is why I registered him in January 2007 in the dormitory of the Ihlas Foundation. He chose that dormitory himself. After one and a half to two months the director of the dorm called me and said that Emre was not obeying the rules, that he was loud at night, switching on the lights, and that I should take him from the dorm, which I did."[81]

The three other suspects, Salih Gurler, Hamit Ceker and Cuma Ozdemir, lived in the same dormitory. Salih Gurler had moved into the dorm in December 2006, having arrived from a small town about 60 km from Malatya.[82] Hamit Ceker and Cuma Ozdemir had also come from neighbouring provinces.[83]

Emre later told prosecutors that he had heard about missionary activities for the first time in the fall of 2006, during an internship at a local newspaper.[84] It was there that he met a mysterious man, Bulent Varol Aral, who worked for only a few days at the paper. Emre told prosecutors:

"[H]e knew almost everything, there was no topic he didn't know about … He said that Christianity and missionary activities were bad, and that they had links to the PKK … He explained that Christianity and missionary work had the goal of destroying the country. Then I said, ‘Someone has to say stop to this,' and he answered ‘Then come on and say stop'. When I said, ‘How will this work out?', he said ‘Then we will guarantee you state support.'"[85]

Emre subsequently contacted a Christian internet site, he told prosecutors, to ask whether there were Christians in Malatya. Emre left his mobile number. A few days later he was contacted by Necati Aydin.[86] Emre began to visit Necati regularly, feigning interest in becoming a Christian. The two met at the Zirve office on six different occasions. Emre later told prosecutors about his plans at the time: "As a result of my investigations I thought to myself that there had to be a counterresponse to the things they were doing. So I had the idea that I should take them hostage and question them about their activities to get more information."[87]

Emre also started discussing his plans more intensively with Salih, Hamit and Cuma.[88] As Hamit told prosecutors,

"About four months [before the murder in April 2007] Emre Gunaydin called us, Salih, Cuma and me, to the smoking room of the dorm to tell us about the increase in missionary activities … Emre did all the planning and we implemented it."[89]

Abuzer Yildirim, the only suspect who did not live in the dorm, had already met Emre back in 2005. He had been working at the Malatya cotton mill. In his testimony he stated:

"Emre told us that missionary activities were many and dangerous, that only in Malatya there were 50 churches and that they already bought two mosques to turn them into churches. If we did not stop them we would lose our religion and they would kill our children. These words influenced me a lot and made me sad. Emre said that he planned to eliminate those doing missionary work in our country, but that he would do this more on his own."[90]

Abuzer Yildirim also told the prosecutors that Emre was clear about his intention to kill Wolfgang Hade, the German missionary who was Necati's brother-in-law and lived in Western Turkey.

"Emre told us that he would go to Konya and kill Wolfgang, whom he presented to us as the leader of missionary activities in Turkey. According to Emre's statements, the missionary churches were secretly involved in terrorist activities and supporting terrorism."[91]

The last time that Emre met members of the Malatya Christian community before the murder was at an Easter celebration in the Altin Kayisi (Golden Apricot) Hotel on 8 April 2007. He was welcomed at the door by Ugur Yuksel and Tilmann's wife Susanne. A few days later he purchased gloves, ropes and three guns, and rented a car. On 16 April Emre met Hamit, Salih and Abuzer at the Eftelya coffee house. Some of them also brought guns. Cuma Ozdemir told prosecutors later that he had wanted to drop out:

"Prior to the event I struggled hard to tell them that I would not participate and even tried to dissuade them. Emre strongly rejected my suggestions and threatened to shoot me if I dared to leave. He also threatened to kill members of my family, relatives and acquaintances. He threatened Hamit in the same way."[92]

On 18 April, a Wednesday, Emre got up early. He later told prosecutors:

"At seven in the morning on the day of the incident I met with Cuma, Hamit, Abuzer and Salih for breakfast at a cafe near Zirve. Abuzer and I went upstairs to Zirve, but it was closed. Then we went to my father's sports centre. Thinking that something could happen to us I said, ‘I will write a farewell message to my relatives.' The friends also wrote something; then we prayed and went to Zirve again. Abuzer and I went upstairs. Abuzer had a knife and a gun, I had a knife. We rang the door bell and someone opened the door; inside were Necati, Ugur and the German."[93]

The first hearing took place on 22 November 2007 in a crowded courtroom of the Malatya Third High Criminal Court. The presiding judge was seated on an elevated platform.[94] Next to him sat the two state prosecutors who had put together the 47-page indictment, submitted on 5 October 2007.

According to the indictment, the victims died as a result of severe wounds caused by a sharp object, which resulted in perforation of veins, arteries and internal organs, as well as internal and external bleeding. One of them, Necati Aydin, was also strangled with a rope.[95]

Seven people were indicted at first. The indictment considered the five main suspects as having formed an "armed terrorist organization."[96] All five – Emre, Salih, Hamit, Cuma and Abuzer – were charged with "killing more than one person in the framework of the terror organization's activities."[97] Emre was additionally charged with being the organization's leader and founder.[98] The prosecutors demanded a triple life sentence in solitary confinement with no possibility of parole for each of the five main suspects.[99]

Two other people were indicted but not arrested. One was Kursat Kocadag, who had kept a gun for Emre. Kocadag was supposed to take part in the raid but, as he claimed, had pulled out four months before the murders.[100] In his testimony Kocadag notes that Emre was telling people "that they [Christians] planned to kill three out of five children and that he [Emre] would kill them after getting to know them better. When he asked whether I would be part of that, I said no."[101] The seventh accused was Mehmet Gokce, who was allegedly meant to copy the hard drive of the computer from the Zirve office. Kursat Kocadag and Mehmet Gokce were both charged with abetting a terrorist organisation.[102]

At the opening hearing the seven defendants sat in front of the judges, accompanied by the gendarmerie. The defendants' lawyers were initially all from Malatya and assigned by the court. Behind the accused sat friends and relatives of the victims, journalists, national and international observers, and diplomatic representatives.

There were also 17 lawyers representing the victims' families.[103] The Association of Protestant Churches had approached a number of lawyers known for their commitment to minority rights. The legal team assembled in Malatya turned into a who's who of Turkish human rights defenders. There was Orhan Kemal Cengiz, the legal advisor of the Protestant Association and a columnist for Turkish daily Zaman and English-language Today's Zaman, who came from Ankara. Sezgin Tanrikulu came from Diyarbakir, where he had defended Kurdish victims of human rights abuses. Ergin Cinmen and Erdal Dogan, who represented the Dink family in the Hrant Dink murder trial, came from Istanbul. So did Fethiye Cetin, another human rights lawyer close to the Dink family and a leading voice in the debate on Turkey's reconciliation with its past.[104]

The lawyers representing the victims' families did not see this as an ordinary murder case; as far as they were concerned, much more was at stake.

Having worked for the Association of Protestant Churches as a lawyer, Orhan Kemal Cengiz wrote the first report commissioned by the association back in 2002.[105] In it, he examined the discrimination of Christians in Turkey.[106]He later wrote a handbook on proper documentation and litigation of torture cases, a manual on combating torture for judges and prosecutors, and a booklet on freedom of thought, conscience and religion.[107] In 2003, he set up the Human Rights Agenda Association (HRAA).[108] All throughout, he defended the rights of the Greek Orthodox community, of conscientious objectors, of Turkish Armenians, and of Kurds not only in court rooms but also in his newspaper columns.[109]

For Cengiz, the Malatya case was personal. As he wrote in his first op-ed following the murder, "Necati Aydin had been a client of mine for the last seven years and I know very well what a nice, lovely person he was." At the same time, Cengiz viewed the crime in Malatya as a turning point for Turkish society as a whole:

"Turkey, more than at any other time in its history, is under a dangerous threat … This threat is Turkey's rising intolerance and inability to accept others, more than at any time before … We know this won't be the last incident. But we hope with all our hearts that it ends here."[110]

In another column, published on 1 May 2007, he wrote:

"For a long time I had been expecting that something would happen … There had been signs. Christians were beaten, their churches were stoned and set on fire and they had received threats every day. Every single day there was news about the treacherous plans of missionaries in the local and national newspapers and on TV stations … For a long period of time the seeds of intolerance, racism and enmity against Christianity have been sown in Turkey. Now those seeds are being harvested one by one. The murder of Father Santoro, Hrant Dink, and the Malatya massacre are in a sense connected."

Cengiz pointed out that the security forces should have been able to prevent these crimes:

"In all the cases security forces had some intelligence and prior knowledge about the perpetrators and their plans, but somehow they did not follow up on the signals and warnings."[111]

On 22 November 2007, the day of the first court hearing, Cengiz repeated his accusation:

"If state officials keep saying every day that Turkey is in imminent danger, that there are internal enemies of this country, that missionaries are the agents of foreign states who try to break up Turkey and so on, such horrible crimes are inevitable."[112]

Some of the other lawyers suspected that state institutions had a more direct role in the killings. Erdal Dogan, an Istanbul-based lawyer who had also defended Hrant Dink, suspected a link to the "deep state" from the very outset. "I read the first documents about the trial, the indictment, the statements of the suspects," he said. "If you are of normal intelligence, you see that there is something bigger behind that."[113] In November 2009, after two years of court hearings, Cengiz was to come to a similar conclusion:

"It is crystal clear. There is a much bigger agenda and much more complex connections. Everything had been planned, but not by them, by other people. They are just puppets."[114]

The interrogation of the suspects in court started on 14 January 2008. The accused all denied that they had intended to kill anyone – despite having brought guns and knives – when they entered the Zirve office. On 9 June 2008 even Emre denied direct involvement in the killings. "I did not tie up anybody," he said. "The three persons who died were tied up by Cuma and Hamit. I did not stab anybody." Emre also claimed that he did not know why the others wanted information from the Zirve office.

"Abuzer and Salih said that they needed the information from the publishing house for themselves, Cuma and Hamit said that they would pass it on to the press. I didn't ask them why they needed it."[115]

The accused told the court that before the murder the victims had admitted to working with Kurdish terrorists and intending to "kill Muslims". Emre gave prosecutors an account of the discussion that took place in the Zirve office moments before the triple murder:

"We started talking. Necati said bad things about Islam. He said that Christianity was good and praised the PKK. I got mad at what he said … Ugur said America and Israel were behind them and that the goal was to get rid of the Koran. He said: ‘We took Iraq, we will take Syria. Kurdistan will be independent; and of every five born Turkish children three will be killed'."[116]

Abuzer also blamed Ugur Yuksel for provoking him and the others.

"Ugur said they will rape our sisters and mothers and then kill them. Emre said, ‘Let's see who will kill whom,' and walked towards him. Ugur was still cursing. I punched Ugur in the face. I got blood all over me. My stomach was upset. I went to the bathroom. A little later Emre came. His hand and knife were bloody. He washed his hand. They would have killed our children. He asked, ‘What kind of man are you?' I didn't understand. When I got back I saw Necati lying in his blood. When I told Emre, ‘What's that?', he said they should die instead of our children … Later I went to the room next door. I thought my life was over and I cried and put the CDs on the table. When I returned to the room where my friends were, Emre was pressing a towel to the face of the foreigner with one hand, and holding a knife with the other. The knife was bloody. I went to the room next door. There I put all the CDs in the PC bag. I told Emre ‘I found everything, let's go!'"[117]

Salih told the court a similar story:

"Emre went to the bathroom again. When he got back, he told Necati that he was doing the wrong thing by dividing the country. Necati told Emre, ‘Fuck you, faggot!' Then Emre took his knife out and told them to lie down and threatened to kill them if they didn't. He pressed the knife to the German's neck. At that moment we also took our knives out spontaneousely. Then everybody lay down. While Necati was lying on the floor he told Emre that he would fuck his mother and sister. In response to this, Cuma tied Necati's hands behind his back, and then the German's. Emre tied up Ugur."

"Emre gave me a rope and pointed to Necati and told me to kill him … Because I was afraid of Emre, I put the rope around Necati's neck. I strangled him a little. Then I said I couldn't do it and stopped doing it. Then Emre went towards Necati. I stood up and tried to hold Emre back. I told him to calm down. At that moment the knife in Emre's hand cut my hand. Then Emre stopped. A little later Necati cursed again. While Necati was cursing Emre started stabbing him in the neck. After a short while Emre jumped on the German's head. Later I saw that Emre was stabbing the German in the back and neck."[118]

During the court hearings, Emre's associates all claimed not to have been aware that Emre planned to kill the Christians. According to Salih, Emre "said that the ropes were necessary to tie people so that they would surrender information more easily and that we needed the knives to protect ourselves."[119] Cuma added his account of the day before the murders:

"I asked them the reason for buying the knives. They said they were going to use these knives to threaten. When I asked Emre what we would need the weapons for, he said he would explain this later. After we left the hardware store, Salih parked the car. I saw a gun, rope and gloves in the trunk. I asked what these were and what they were for. He said that he was going to use them to frighten them and that I didn't need to worry."[120]

Abuzer testified that "Emre said that on Monday we would go to Zirve Publishing, that we would get information from the missionaries there, and then go to Wolfgang [Hade] in Konya to resolve their links to the PKK."[121] The suspects' testimony in court, however, was at odds with their earlier statements. Shortly after their arrest in April 2007, Hamit had told prosecutors:

"I understood from what Emre told us that his fight against this group would be very decisive and if needed would continue until death or until they would be eliminated … He said that after killing the missionaries in Malatya, the actual goal was killing Wolfgang [Hade], and that he would do this on his own if necessary. He added that doing this would bring us great financial benefits … From time to time Emre told us about his plans how to kill and eliminate the missionaries. We wanted to eliminate this harmful group because of our love towards our country and nation."[122]

The other four suspects all described Emre as extremely aggressive. As Cuma put it, Emre intimidated everyone from the very outset:

"We told [Emre] that we would not accept his offer and that we had come to Malatya to study. He told us there was no turning back; otherwise he would put a bullet in our head and kill our families. He said we would die. He threatened us. I never saw him with a gun, but he carried a knife. It was a small knife with a wooden handle. Emre spoke harshly and yelled."[123]

They also described Emre as someone who enjoyed close connections to the local police. Hamit told the court:

"If I had not accepted his invitation, I thought he would have harmed me and my family … We thought about going to the police because of what Emre had told us. But Salih told me that Emre was closely acquainted with the police director. That's why we didn't do it."[124]

All suspects told the court about Emre's immunity from police scrutiny prior to the murder. Abuzer told prosecutors that he "did not dare to inform the police because Emre was close to the police director and got help with the knife stabbing incident."[125] He was referring to an event in February 2007, which Salih described during the fifth court hearing:

"Emre once came to us after having stabbed a man he saw together with his girlfriend. He told us about the stabbing. He quickly changed clothes, went to the barber to get a shave and took me and Cuma with him to the Sumer police station. There he talked at the door with a policeman. He went inside and came out soon. Then he came over to us. The policeman told Emre that they would not know that he did it and that the file would be closed as if the attacker had been unknown. They told him, ‘If they make a search and find out that you did it, we will let you know.' This is what Emre told us. That's why we stopped short of telling the police what Emre was planning."[126]

Cuma recalled the same incident:

"Salih, Emre and I went to the Sumer police station. We waited across the station and Emre went in. He [Emre] said there were police he knew and that he'd managed the situation and the case was closed."[127]

One month later, in March 2007, Emre stabbed a student inside the dormitory. Hamit, who was in the dorm at the time, later testified:

"I saw Emre and another student, Fatih, taking Onur down to the study room. I heard that Onur had borrowed money from other students and hadn't paid back his debt. Later I heard Onur crying and screaming. When I arrived I saw Emre hitting Onur in the face with a bread knife and Fatih hitting him with his fist. Emre stabbed his body several times and Onur fell to the floor. Emre and Fatih escaped … This event was not taken to trial. I understood from this behaviour that Emre would use violence if someone was not doing what he wanted. After this event Emre was kicked out of the dorm."[128]

Emre had spent a total of two months at the dorm.

After the second hearing on 14 January 2008, Orhan Kemal Cengiz pointed to links between Emre and the chief of police in Malatya.

"However prepared the defendants' statements were, it was still possible to find out details such as the close relationship between Emre Gunaydin and the chief of police. Of course, the question is whether, despite this information, we will be able to go beyond the current picture."[129]

But Emre's personal links to the police were not his associates' only source of concern. As Salih, who came from the same village (Dogansehir) as Emre's family, told the court,

"Emre also said that there were seven files about him at the police, that he had been in prison, and that his elder brother was with Sedat Peker. [Emre's] uncles were among the leading mafia groups in Turkey. I heard in Dogansehir that his uncles were in the mafia. After he came to the dorm, I started to go wherever Emre went. I didn't object because I was afraid. When we said no, he would yell at us."[130]

Sedat Peker, born in 1971, was a household name in Turkey, having become one of the most famous and flamboyant organized crime figures of his generation. Between 1988 and 2002 Peker had spent more than 2 years in prison on charges ranging from organised crime to armed assault. In 2004 he was arrested again and sentenced three years later to 14 years for involvement in organised crime.[131] Peker is claimed to have served with Veli Kucuk, a retired general and alleged founder of the secret Gendarmery Intelligence and Counter-Terrorism Department (JITEM), in the gendarmerie in Kocaeli in the 1990s. [132] Peker, known for his Pan-Turkic ideas, has many supporters among Turkey's Grey Wolves ultra-nationalists. He maintains a website, featuring hundreds of messages from his fans since 2008. More than 25,000 members are listed on his Facebook site. In 2008 both Veli Kucuk and Sedat Peker (already in prison for another crime) were charged with belonging to the alleged Ergenekon terror group.

Hamit Ceker also told prosecutors that

"Emre had no worries about us getting caught. He always said we would not be caught, but if we were caught, he would accept all the guilt and that especially his uncle, whose name I don't remember and who has mafia contacts, would be of great help for us, and we were convinced by these statements."[133]

Abuzer Yildirim also claimed that he was "not afraid of Emre, but of the powers behind him."

"The Saturday before the incident when I was sitting at the Rainbow Teahouse, Emre came. He said we would go to the Zirve publishing house on Monday and we would get information from the missionaries … When I said this would not happen, he said ‘I am not offering it to you. You have to. Your family is known by the state. If you don't come, things you can't even imagine will happen to your family'."[134]

On 5 February 2008 a 24 year old inmate named Metin Dogan sent a letter to the Malatya Public Prosecutor from a prison in Southern Anatolia.[135] Dogan was serving a 16-year sentence for murder. In the handwritten letter he introduced himself as somebody who knew Emre Gunaydin from the time they spent together in the Grey Wolves organisation (Ulku Ocaklari) , an ultranationalist youth organisation close to the nationalist National Movement Party (Milliyetci Hareket Partisi, MHP).[136]

"From my childhood I grew up in the Malatya Ulku Ocaklari. I did many activities for them. I took active jobs. So I was the most trusted, the number one man in the eyes of the organisation."[137]

Dogan wrote that in 2005 Burhan Coskun, the head of the Malatya chapter of the Ulku Ocaklari called him to the provincial office of the MHP.[138] There, Coskun and others present asked Dogan to kill the Christians at the Zirve office.

"Namik Hakan Durhan, the former MHP Member of Parliament from Malatya, told me that ‘You will call the Zirve Publishing house and threaten them.' I called them, Adnan from Zirve answered and I threatened him.[139] After threatening I hung up the phone."

"‘This job suits you my lion, you will do it. You will kill whoever there is at Zirve,' [they told me]. Then the man who had introduced himself as major general said we will save you, don't worry at all. Namik Hakan Durhan explained how to finish the job and that in the end they would give me 300,000 USD. He said that they would inform me about the place and the date of the murder."[140]

During a hearing in May 2008 Emre denied even having heard of Metin Dogan.[141] Still, the court called Dogan as a witness.[142] He testified on 4 July:

"I am quite close with Emre. We were together in the Ulku Ocaklari. I am also an athlete. I was involved in tae-kwon-do, Emre was involved in kickboxing. He is lying. He knows me. I have a lot of information about the event. I was involved in it when Emre was not yet in. I grew up in Ulku Ocaklari."[143]

In court Dogan described again the meeting where he was allegedly invited to kill the Christians:

"Burhan Coskun, the Ulku Ocaklari Malatya president, called me on my mobile in August 2005. He said that I should come to the MHP building [the office of the Nationalist Movement Partyi]. I went. The MHP provincial president Ekici, the ex-MP Namik Hakan Durhan (MHP) and a 50-55 year old man named Hikmet Celik who introduced himself as a major general and whom I had not seen before, and Burhan Coskun were there. I sat down. We had discussed the distribution of bibles and the deceit of the young before in Ulku Ocaklari … I should get two strong youngsters and raid the publishing house with them, but those youngsters shouldn't know them. They asked me not to take them from Ulku Ocaklari. They told me to find them in Tastepe [a quarter in the northeast of Malatya].

"They said we should raid with weapons. I asked what we should do if there were others present there … They told me that we should also kill them. They said I would not be caught if I listened to them, but if I didn't listen to them and we were caught, we would be released within two years. Later I should bring the two youngsters to Santral Hill and kill them too." [144]

Dogan explained that a second meeting followed with ex-MP Namik Hakan Durhan and Burhan Coskun, the local Ulku Ocaklari president. "They said they were going to have me carry out this activity: the world would think it was them but that no one would be able to prove it," he told the court.[145] One and a half months after these meetings, Metin Dogan went to Mersin, where his brother happened to be killed in an unrelated incident. Dogan killed his brother's murderer and went to jail. He told the court about a message he received from a prison guard in January 2007:

"This guard approached me in prison in Mersin. He said that Namik [Hakan Durhan, the former MHP Member of Parliament] had sent his greetings and asked whether I needed anything. He also told me that he and Namik had no secrets and that the job that I was supposed to do will be done by Emre Gunaydin and that I should be quiet."[146]

Metin Dogan claims that Emre's uncles "were known in Malatya province. They were like a criminal gang."[147] (When asked to do so, however, Dogan could not recall their names[148]) Dogan also claimed that Ulku Ocaklari and the police "are very close. Many policemen come and go. [Burhan] Coskun told me to commit the murders with a knife, because, he said, it would be too difficult to arrange things with the police if it was done with a gun."[149]

Ex-MP Namik Hakan Durhan was later questioned by the Malatya prosecutors. The content of his testimony is not part of the court files.[150] In May 2008 Durhan reacted to Metin Dogan's accusations in an open letter:

"I was not in Malatya when this conversation was supposed to have happened … This information is completely baseless and falsified. It is defamation against me and against the party of which I am a member."[151]

So far, nobody from Malatya Ulku Ocaklari has been called to testify in court.

Emre Gunaydin first told prosecutors about Varol Bulent Aral, a mysterious man about whom little is known, in 2007. Emre, who met Aral while both worked at the Malatya Birlik Newspaper in summer 2006, claimed that Aral had called on him to put a stop to the activities of Christian missionaries out to destroy the country. "Come on and say stop," Aral allegedly told Emre. "We will guarantee you state support.'[152] Subsequently asked about this in court, Emre retracted his earlier statements, but it was enough to invite Aral to court as a witness.[153]

At the time of the Malatya murders Varol Bulent Aral was in jail, having been arrested in February 2007 for illegal possession of a Kalashnikov. After his release he was again imprisoned in Adiyaman, a town located some 130 kilometers from Malatya, for insulting and threatening the Chief of Police in Adiyaman.

Aral testified as a witness in the Malatya trial on 16 October 2008:

"I know Emre Gunaydin from the Malatya Birlik newspaper where we worked for three days in the fall of 2006. … We talked for about half an hour about the PKK. There was no conversation about missionaries or the victims."[154]

Of his earlier arrest, Aral said that he found the Kalashnikov "in the bag of a 10 year old boy, which had looked suspicious, in a parking space in Adiyaman. I wanted to bring it to a nearby police station, but since I had a problem with one of the policemen [in Ayiyaman] I didn't want to bring it there. I wanted to bring it to a more distant police station."[155]

Even now little is known about Aral's life. Aral described himself as a person suffering from bad health and depressions and who, "not having a permanent address," was staying with "a lot of people" and living on only 10 TL (EUR 5) per day as a day labourer.[156] An indictment described Aral as an advertiser ("reklamci") who had worked briefly at the Malatya Birlik newspaper.[157]

In court Aral was also asked about his personal organizer, which was found at the Malatya Bus Terminal on 30 January 2008 and contained the names of various ultranationalists including Kemal Kerincsiz, one of the suspects in the Ergenekon case. Kerencsiz is an ultranationalist lawyer specialised in filing complaints against Christians and Turkish liberal intellectuals for denigrating Turkishness. "These notes concerned research for a book I am writing entitled ‘Teferruat' [Details]," Aral explained.[158] "I am not an informant"[159], he also claimed. "I still cannot understand how Emre could do this. Emre and the others are too inexperienced."[160] During the same hearing Emre was asked whether Aral persuaded him to commit the murders. He used his right to silence and did not respond.

On 2 February 2009, however, Emre changed his mind and gave a statement to prosecutors incriminating both Aral and a second person, the Christian convert Huseyin Yelki who had worked with the missionaries in their office, as having instigated the raid on the Zirve office. Emre claimed that Aral had introduced him to Huseyin Yelki and that he had met with Yelki on numerous occasions after Aral left Malatya province in October 2006.