Sex and Power in Turkey - Feminism, Islam and the Maturing of Turkish Democracy

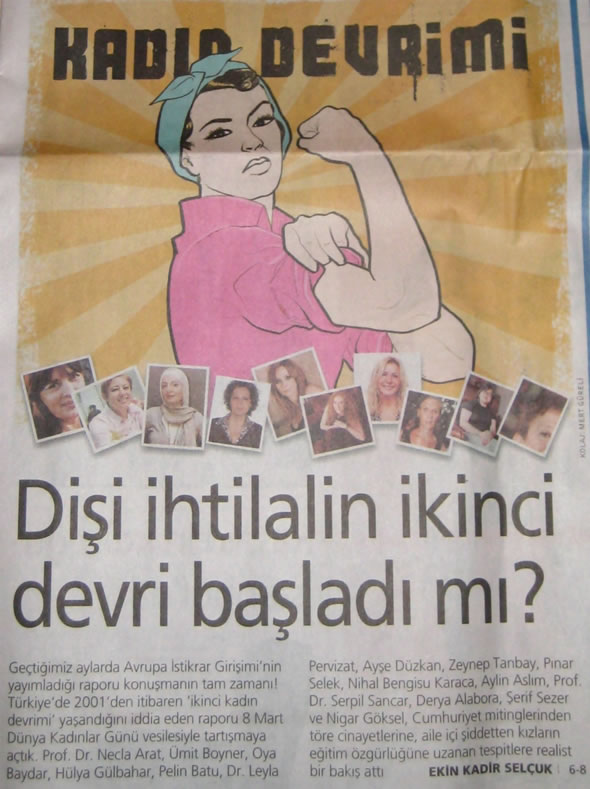

"The European Stability Initiative prepared a report on Turkey entitled 'Sex and Power: Feminism, Islam and the Maturing of Turkish Democracy.' The argument is that from 2001 onwards legislative changes, initiatives to combat domestic violence and efforts to increase the schooling of girls triggered a 'female revolution.' We did not miss the opportunity to discuss this claim on 8 March Women's Day".

Necla Arat (founder of the Center for Women's Research and Education at Istanbul University): "The report frequently states that the most radical reforms were conducted under AKP's rule… The report also denigrates the Republican demonstrations… The rights and the wrongs of this partial report should be debated."

Leyla Pervizat (Feminist Researcher): "The report claims that Turkey, legislatively, is now post-patriarchal. However there are still serious problems… The Turkish Penal Code does not use the term "honour killing." Moreover, the state still allows men to be in charge of women's honour."

Aylin Aslim (singer), "I am not aware of a revolution. The government is men, the laws are men, the decision makers are men."

Nihal Bengisu Karaca (journalist): "For matters that could very well stay the same for centuries, the law needs to pioneer change. It is interesting that most of the changes that enhanced women's status occurred during the AKP period".

Mediz (Media Tracking group of Women): "ESI's report relates the potential for change and the legal transformation of Turkey to EU member states. As Turkey is preparing for EU membership, the report emphasizes the positive developments… It might be too early to call it a 'revolution'".

- Dünya Bülteni, Aynur Erdoğan, "Erkek aklına eklemlenen feminizm" ("Feminist upgrade for the male mind") (30 April 2011)

- CNN TURK, Mithat Bereket, Interview with Gerald Knaus and Nigar Göksel on feminism and Islam in Turkey (26 December 2007)

- Hürriyet, Sefa Kaplan "Türkiye'de kadın devrimi yaşanıyor" (26 December 2007)

- Radio Multikulti, Sevim Ercan "AKP’nin kadinlara yaklaşimi değişti mi?" (16 November 2007)

- EDAM, Nigar Göksel "Women and the changing face of Turkey" (Fall 2007)

- BBC Woman's hour "Turkish women's groups attack draft constitution" (Interview with Gerald Knaus) (19 October 2007)

- The New York Review of Books, Christopher de Bellaigue "Turkey at the Turning Point?" (27 September 2007)

- Zaman, Şahin Alpay "AKP ve kadınlar" (25 September 2007)

- SaudiDebate, Mona Eltahawy "Success of Turkey’s AK Party must not dilute worries over Arab Islamists" (4 September 2007)

- Prospect Magazine, Gerald Knaus (opinion) "Who will free Turkey's women?" (August 2007)

- Turkish Daily News, Mustafa Akyol "The sum of all secular fears — a sequel" (21 July 2007)

- Today's Zaman, Abdulhamıt Bılıcı "What will the Turkish electorate say at the polls?" (21 July 2007)

- Format, Gerald Knaus (guest commentary) "Es steht viel auf dem Spiel an diesem Wahltag" (July 2007)

- Liberazione "Le donne turche per la prima volta protagoniste" (21 July 2007)

- El Mundo, Fatima Ruiz "Las mujeres emprenden la revolucion turca" (21 July 2007)

- Svenska Dagbladet, Bitte Hammargren "AKP bakom kvinnoreformer" (20 July 2007)

- The Wall Street Journal, Matthew Kaminski "Turkish Test" (20 July 2007)

- DIE ZEIT, Michael Thumann "Anatolien schlägt zurück" (19 July 2007)

- BBC, Sarah Rainsford "Türk kadininin eşitlik için uzun yolu" (19 July 2007)

- BBC, Sarah Rainsford "Women’s equality is one of the central issues in Turkey’s July 22nd elections" (18 July 2007)

- BBC, Sarah Rainsford "Turkish women's long road to equality" (18 July 2007)

- Der Standard, Adelheid Wölfl "Auf dem Weg ins Post-Patriarchat" (14 July 2007)

- The Economist, "In search of the female voter" (12 July 2007)

- Bianet, "Kadınların İlerlemesi Kağıt Üzerinde Kaldı" (11 July 2007)

- Akşam, Mehveş Evin, "Türkiye'de seks ve güç" (10 July 2007)

- Akşam, "Kadın hakları en çok 2001'den sonra gelişti" (1 July 2007)

- Sabah, Soli Özel, "Cinsiyet ve iktidar" (24 June 2007)

- Dagens Nyheter, Henrik Berggren, "Gnosjö-islam" (21 June 2007)

- Falter, Katharina Knaus, "Türkische Mythen" (20 June 2007)

- Turkish Daily News, Reeta Çevik, "Gender equality given carrot and stick in ESI report" (18 June 2007)

- Today's Zaman, Sahin Alpay, "Sex and power in Turkey" (18 June 2007)

- Turkish Daily News, Mustafa Akyol, "Sex matters -II- (The tragedy of Kemalist feminism)" (16 June 2007)

- Turkish Daily News, Mustafa Akyol, "Sex matters-I- (Toward a post-patriarchal Turkey)" (14 June 2007)

- Süddeutsche Zeitung, Kai Strittmatter, "Die Frau als Besitz des Mannes" (2 June 2007)

Turkish Policy Quarterly Vol 6, No. 1 (Spring 2007) "Women in Turkey: Prospects and Challenges"

"Pay attention to every corner of the world, we are at the eve of a revolution. Be assured, this revolution is not going to be bloody and savage like a man's revolution."

Fatma Nesibe, feminist lecturer, in Istanbul 1911

In the history of the Turkish Republic, there have been two periods when major improvements were made to the status of women. One was the 1920s, the early years of the Republic, when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk outlawed polygamy and abolished Islamic courts in favour of secular institutions. This first period of reforms is well known and celebrated in Turkey.

The second major reform era has been the period since 2001. Reforms to the Turkish Civil Code have granted women and men equal rights in marriage, divorce and property ownership. A new Penal Code treats female sexuality for the first time as a matter of individual rights, rather than family honour. Amendments to the Turkish Constitution oblige the Turkish state to take all necessary measures to promote gender equality. Family courts have been established, employment laws amended and there are new programmes to tackle domestic violence and improve access to education for girls. These are the most radical changes to the legal status of Turkish women in 80 years. As a result, for the first time in its history, Turkey has the legal framework of a post-patriarchal society.

The reforms of the 1920s were carried out by an authoritarian one-party regime. Women were given the right to vote at a time when there were no free elections. Generations of Turkish women were taught to be grateful for Ataturk's gift of freedom and equality. However, legal inequality of men and women remained in place in Turkey throughout the 20th century, long after it was abolished in the rest of Europe.

The reforms of the last few years have come about in a very different way from those of the 1920s. They were the result of a very effective campaign by a broad-based women's movement, triggering a wide-ranging national debate. The current AKP government proved willing to work constructively with civil society and the main opposition party CHP. This open and participatory process produced the most liberal Penal Code in Turkish history. It represents a significant maturing in Turkish democracy.

There are some who fear that Turkey may be turning its back on its secular traditions. Some of the loudest voices come from Kemalist women, who insist that the rise of 'political Islam' represents an acute threat to the rights and freedoms of Turkish women. There have even been calls for restrictions to Turkish democracy, to protect women's rights. Yet such an 'authoritarian feminism' is out of touch with the reality of contemporary Turkey and the achievements of recent years.

Turkey has a long road ahead of it in narrowing its gender gap. In a recent international study, Turkey ranked an embarrassing 105th of 115 countries – far behind the worst-ranking EU member. Improving gender equality will involve tackling a series of deeply entrenched problems, from improving access to education in rural regions to removing the institutional and social barriers to women's participation in the workforce. Elections in July this year will test the commitment of Turkey's political parties to increasing the number of women in parliament.

It is these issues which deserve to be at the centre of the current political debate in Turkey. And it is only the maturing and further development of Turkish democracy that holds out the promise of a genuine liberation of Turkish women.

In 1911, an Ottoman feminist, Fatma Nesibe, gave a series of lectures to an audience of 300 women from Istanbul's social elite. Quoting John Stuart Mill's The Subjection of Women, she talked about the new concept of women's rights and their advocates emerging in Western countries. Describing Ottoman women as oppressed, she noted that "law, tradition, pleasure, indulgence, property, power, appreciation, arbitration… are all favourable to men." She boldly predicted that the Ottoman Empire, like the rest of Europe, was on the eve of a "feminine revolution".

It was an optimistic call from the heart of an Empire on the verge of collapse. What one US writer has called "the longest revolution" – the legal and social emancipation of women – at that time had hardly begun anywhere in the world. At the beginning of the 20th century, most societies were patriarchal. Women lived under the legal and moral authority of their father until marriage, when the husband took his place. The German civil code in force in 1900 stipulated that "to the husband belong the decisions in all affairs of the married life in common." In France, the Napoleonic tradition had bequeathed a civil code requiring a wife's 'obedience' to her husband. Even in Sweden, forerunner of the global movement for gender equality, the first Marriage Act embodying an explicitly egalitarian conception of marriage came into force only in 1915. The Ottoman family laws at the time were based on traditional Islamic law (Sharia).

A century later, the feminine revolution that Fatma Nesibe anticipated had changed the status of women around the globe. In Europe, relations between men and women had entered a new historical stage, which the Swedish sociologist Goran Therborn has called "post-patriarchy".

"Post-patriarchy means adult autonomy from parents and equal male-female family rights – not just as proclaimed rights but as justiciable claim rights. This is a major historical change, virtually unknown and unpractised anywhere before, and as we have just seen, it is a recent change."

Yet at the end of the 20th century, Turkey, alone among European countries, remained firmly within the patriarchal tradition. Turkish women had unequal status under both civil and criminal law, with the husband formally recognised as head of the household and a Penal Code based on the notion of family honour, rather than individual rights.

The legal situation reflected social reality: at a meeting of the World Economic Forum in Istanbul in November 2006, a table measuring the "gender gap" (inequality between men and women) put Turkey 105th of 115 countries, behind Tunisia, Ethiopia and Algeria. Today, Turkey continues to lag behind every other European country in almost every measure of gender equality. It has the lowest number of women in parliament, the lowest share of women in the workforce and the highest rates of female illiteracy. The perception that, in this highly sensitive area, Turkey is out of step with other European societies has become central to European debates on Turkey's EU accession. In both France and Germany, opponents of Turkish accession have made this a key plank of their campaign. The issue also plays to anxiety within European countries about the integration of their own Muslim communities.

Over the past 18 months, a team of ESI analysts has been researching the changing reality of women in Turkey. We talked to dozens of Turkish politicians, activists, academics and businesspeople. Our research took us from women's shelters in wealthy areas of Istanbul, through the growing urban centres in Turkey's southeast, to small towns near the Iranian border. We sought to answer two questions: what are the root causes of Turkey's vast gender gap; and what is being done by Turkish political actors to try to close it?

If this report had been written in 1999, the year Turkey gained the status of candidate for EU membership, its conclusions would have been deeply pessimistic. Writing in 2007, however, the perspective shifts dramatically. Recent amendments (2004) to the Turkish Constitution assert that "women and men have equal rights" and "the state is responsible for taking all necessary measures to realize equality between women and men" (Article 10). A new civil code (2001), reforms to the employment law (2003), the establishment of family courts (2003) and a completely reformed penal code (2004) have brought about comprehensive changes to the legal status of women. These are the most radical reforms since the abolition of polygamy in the 1920s. As a result, for the first time in its history Turkey has the legal framework of a post-patriarchal society.

These reforms also reflect profound changes in Turkish democracy. The 2004 reforms to the Penal Code were passed by a parliament in which the conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) held an overwhelming majority, following an effective and professional campaign by women's organisations. To the surprise of many of the activists themselves, the AKP parliamentarians proved willing to engage with civil society and debate the issues on their merits. Turkish women's organisations have emerged as influential political players.

These enormously important legal reforms should not obscure the fact that the gender gap in Turkey remains vast. This report also explores the reality of Turkey's gender gap, including its economic and regional dimensions. It concludes with an assessment of what it might take to finally bring Fatma Nesibe's feminine revolution to Turkey. Recent progress suggests that Turkey may finally be on the eve of this global revolution.

On 27 April 2007, the Turkish military fired a warning shot across the bows of Turkish democracy in the form of a late-night posting on its website. The general staff declared its opposition to the nomination of current foreign minister Abdullah Gul as presidential candidate. It reminded the Turkish government of the military's role as "staunch defender of secularism." It warned that it would display its "position and attitudes when it becomes necessary".

In Turkey, such threats are taken seriously. The 1960 coup ended with the execution of the country's first elected prime minister, together with his foreign and finance ministers. The 1970 coup "marked the beginning of the mass imprisonment of the rebellious young." The 1980 coup saw 180,000 people detained, 42,000 convicted and 25 hanged. Most recently, the so-called 'soft coup' of 1997 saw political parties banned and elected politicians sent to prison on trumped-up charges.

The generals' ultimatum was followed by a series of demonstrations, with one of the largest on 29 April on Istanbul's Caglayan Square to "protect secularism". The speakers at Caglayan, and the members of the organising committee, were almost all women. Nur Serter, vice-president of the Ataturk Thought Association, a nationalist NGO, offered her encouragement to the generals, telling the crowd "we line up in front of the glorious Turkish army." Necla Arat, founder of Turkey's first women's research centre at Istanbul University, announced: "we are here to defend Turkey's secular structure, to stop those who want to change it step by step." Turkan Saylan, president of the Association in Support of Contemporary Living, warned that the AKP government "is now working on the transformation of Cankaya [the presidential palace] into the palace of a religious order." The headline in the Turkish daily Radikal was "Women Power". Nilufer Gole wondered whether 2007 would be remembered as the year of the "feminine coup", marked by an alliance between "secular women and generals".

To outside observers, this may seem an unlikely alliance. But it is not the first time that Kemalist women's organisations have joined hands with the military to challenge the rise of "Islamism".

In the official discourse of the Turkish state, the emancipation of women was accomplished single-handedly by Mustafa Kemal Ataturk between 1924 and 1934, liberating Turkey at a stroke from the influence of Islamic law. Ataturk's reforms granted Turkish women full equality with men well in advance of other European nations, without the need for a protracted struggle. For later generations of Kemalist women, raised on these precepts as articles of faith, the imperative has been to defend this legacy against the dangers of a resurgent Islam by any means necessary – even at the expense of Turkish democracy.

This "nationalist feminism" was consciously constructed during the early decades of the Republic. One of its central myths is the existence of a golden age of gender equality in pre-Islamic Turkish Central Asia. The intellectual Ziya Gokalp (1876-1924), a key figure in early Turkish nationalism, wrote:

"Old Turks were both democratic and feminists… Women were not forced to cover up… A man could have only one wife… Women could become a ruler, a commander of a fort, a governor and an ambassador."

According to Gokalp it was foreign influence that brought this pre-Islamic golden age to an end, until it was finally restored by a nationalist leader.

"Under the influence of Greek and Persian civilization, women have been enslaved and lost their legal status. When the ideal of Turkish culture was born, was it not essential to remember and revitalise the beautiful rules of old Turkish lore?"

This view became enshrined in Turkish history books, under the guidance of the Society for the Study of Turkish History, established by Ataturk himself. Afet Inan, Ataturk's adopted daughter, wrote The Emancipation of the Turkish Woman. It traced Turkish history back to 5000 BC, making the conversion to Islam in the 8th century appear relatively recent. According to Inan, the Kemalist revolution restored Turkey's true national traditions, liberating women from the constraints of Islamic norms and values. As Nermin Abadan-Unat, for many years head of the Turkish Social Science Association, pointed out, "almost all major progressive measures benefiting Turkish women were granted rather than fought for" and had been granted by "a small male revolutionary elite". It took many more years for a new generation of Turkish women historians to challenge this view of early Republican history.

The young Turkish Republic took great pride in promoting a select group of pioneer women through the education system and into public life. The first female doctor (1926), lawyer (1927), judge (1930) and pilot (1932) were held up as symbols of a progressive secularism. Kemalism came to serve as feminism for these proud "daughters of the Republic", even if its benefits never extended beyond a narrow, urban elite. The state made much of granting women the right to vote in 1934, although Turkey was not a democracy at the time. Independent women's organisations were disbanded 'voluntarily', on the basis that they were no longer needed. Their place was taken by Kemalist women's organisations that, according to Sirin Tekeli, one of Turkey's leading feminists, were

"organised to defend the vested interests based on those rights acquired under the single-party era, rather than to extend them and make them more widespread. The main corpus of their activity comprised 'communiqués' published on official days of the republic to praise the 'Kemalist reforms'."

For some Turkish Kemalists, the rise of political Islam has continued to be the most potent threat facing Turkish women. In the late 1980s, organisations like the Association in Support of Contemporary Living (CYDD), which was instrumental in the 2007 demonstrations, were created to defend the achievements of Kemalism against the new prominence of religion in public life. According to Turkan Saylan, president of CYDD, the Islamist threat had never disappeared: after the madrasa (Islamic schools) were closed, Islamists had simply gone underground. When multiparty democracy was introduced after the Second World War, they resurfaced and began openly attacking the system.

This threat appeared acute following election victories by the Islamist Welfare Party in the 1990s. When current prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan was elected mayor of Istanbul in 1994 as representative of the Welfare Party, it prompted an immediate backlash from Kemalist circles. Rumours began to circulate that Welfare Party activists were harassing people in public. The daily newspaper Cumhuriyet wrote that "gangs in favour of Islamic order have been continuing their attacks against young girls and women." Yael Navaro-Yashin wrote about Istanbul in 1994:

"There was a traffic in signed and anonymous faxes throughout private and public offices of Istanbul at this time, calling upon people to unite in the name of the legacy of secularist and modernist leader Ataturk."

As it happened, it was the support of working-class women that carried Erdogan and his party to power; Cumhuriyet wrote at the time, "the dynamo of the Welfare Party is its women." But this was of little comfort to Kemalist women. As one liberal feminist, Pinar Ilkkaracan, put it:

"The secular/Kemalist feminists… perceive the women activists in the Islamic movement as their enemies or reduce them to ignorant beings."

In early 1998, the Welfare Party was shut down and its leaders temporarily exiled from politics, following a decision by the Constitutional Court and pressure from the military-controlled National Security Council. The headscarf ban at universities was tightened. In 1999 Merve Kavakci, who had studied computer engineering in the US, was elected to parliament on the ticket of the Virtue Party, the Islamist successor to the Welfare Party. When she attended parliament with her head covered, the outcry was tremendous: "terrorist", "agent", "provocateur", "liar" and "bad mother" were some of the accusations against her. As one commentator in Cumhuriyet wrote:

"A political party is trying to bring a religion, a sharia, which does not belong to us, by throwing a live bomb to our Grand National Assembly. This is a crime against the state."

Similar arguments are being employed today against the possibility of a Turkish president whose wife wears the headscarf.

Their fear of political Islam makes Kemalist women distinctly ambivalent towards multi-party democracy. The day after the Caglayan demonstration, Zeyno Baran, a Turkish analyst at the conservative Hudson Institute in Washington D.C., wrote that "it is the women who have the most to lose from Islamism; it is their freedom that would be curtailed". Justifying the military's threat of intervention, she noted:

"Turkey does not exist in a vacuum; Islamism is on the rise everywhere… If all Turkey's leaders come from the same Islamist background, they will – despite the progress they have made towards secularism – inevitably get pulled back to their roots."

According to Baran and other Kemalist women, little has changed in the century-old confrontation between secularists and Islamists. Backwards looking and afraid of the majority of their compatriots, the "daughters of the republic" continue to flirt with military intervention in their defence of Ataturk's legacy.

The official story of women's liberation in Turkey – that equality was granted at a stroke of the pen by Ataturk, "for which Turkish women should remain eternally grateful" – proved remarkably tenacious, obscuring a reality that was in fact very different. A prominent Turkish scholar, Meltem Muftuler-Bac, noted in 1999 that

"the seemingly bright picture – Turkey as the most modern, democratic, secular Muslim state that also secures women's rights – is misleading in many ways. In fact, I propose that this perception is more harmful than outright oppression because it shakes the ground for women's rights movements by suggesting that they are unnecessary."

It took time for Turkish women's organisations to break free of this constraint. They did so in several stages.

The first phase was empirical investigation into the reality of Turkish women by a new generation of sociologists in the 1960s and 1970s. For example, the sociologist Deniz Kandiyoti described the changes in family life underway in a village near Ankara in the early 1970s. A growing number of young men were leaving the village for education and employment, creating a new social mobility. For young women, however, life offered no such choices.

"After her brief spell of sheltered maidenhood, a village bride takes her place in her new household as a subordinate to all males and older females… As things stand, one can confidently state that sex roles and especially conjugal roles are least likely to change."

When the sociologist Yakin Erturk examined villages around Mardin in South East Anatolia in 1976, she found a rigidly hierarchical society, where decision making was the prerogative of men. The tradition of bride price reinforced the status of women as the property first of their fathers, and then their husbands. Even the right to education, enshrined in national law, meant little to rural women.

"Eastern regions remain in a state of underdevelopment… Village girls in general have almost no access to either technical training or education of any substantial significance. Although elementary education is compulsory for both sexes, availability of education in the region is a relatively new phenomenon. In Yoncali and Senyurt, schools were opened for the first time in 1958 and 1962 respectively."

Research of this kind began to expose the reality that the reforms of the 1920s had barely penetrated Turkish society beyond a small, urban elite. In 1975, more than half of Turkish women were illiterate. Most were married before the age of 17. Although women served as unpaid labour in the agricultural sector, they made up less than 10 percent of the urban labour force.

Faced with the harsh realities of life for most women, many Turkish academics interpreted the problem as a clash between a progressive legal system and a patriarchal society. The problem was defined as rural backwardness and the persistence of Islamic culture and values. As Turkish feminists put it at the time, Turkish women had been emancipated, but not yet liberated.

It was only in the 1980s that Turkish feminists began to ask more radical questions. Sirin Tekeli, an academic who had resigned in protest against the purges and political controls imposed on Turkish universities after the 1980 coup, became the voice of a new wave of liberal feminists who, as she put it, had "finally decided to look at their own condition more closely." Tekeli's writing drew attention to the paradox between the stereotypes of women's liberation in Turkey, and the reality of women's absence from the political arena. No woman served as government minister until 1987, or as governor of a province until 1991. Tekeli and her colleagues found that the problem was not just with the backwardness of rural society, but with the law itself. Legal emancipation proved to be very limited – a reality that had long been hidden by official ideology.

"Our mothers' generation – both because they got some important rights and were given new opportunities, and because they were forced to do so by repression – identified with Kemalism rather than feminism. The patriarchal nature of the Civil Code, which recognised the husband as the head of the family, was never an issue for them."

Turning their attention to the family as the source of patriarchal values, liberal feminists found that patriarchal values were inscribed into the law at the most basic level. If husbands and wives were supposed to be equal before the law, why did married women require the permission of their husbands to work? Why was extramarital sex by women treated differently in criminal law than when committed by men?

It was the UN Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which entered into force in 1979 and was ratified by Turkey in 1985, that most clearly brought the deficiencies in Turkish law into public view. The Convention requires signatory states to reflect the equality of the sexes throughout their legislation, and to prohibit all forms of discrimination. Discovering that much of its Civil Code was in violation of these principles, Turkey was compelled to issue embarrassing reservations to the provisions of the Convention. It was unable to grant men and women equal rights and responsibilities in marriage, divorce, property ownership and employment.

In political terms, CEDAW accomplished a radical shift of perspective. The yardstick for measuring Turkey's law was no longer the Ottoman past or the Sharia, but contemporary international standards. By highlighting the shortcomings of the 1926 Civil Code, Turkey's reservations to CEDAW set a clear reform agenda for the Turkish women's movement – although it would take another 17 years for their efforts to bear fruit.

Campaigns launched by women's rights activists in the 1980s to reform the Civil Code came to nothing in the face of indifference from the political establishment. It was not until the 1995 World Conference on Women in Beijing that Turkey committed to withdrawing its reservations to CEDAW. It did so in September 1999, but without having amended its Civil Code. From this point on, the EU became an additional influence on the process, with the regular pre-accession progress reports noting the need to bring the Civil Code in line with CEDAW's requirements.

Women's organisations continued to advocate on the issue through the 1990s, using increasingly sophisticated campaigning techniques. A special mailing list (Kadin Kurultayi) for activists was set up, and 126 women's NGOs from all over Turkey joined forces for a national campaign. Women's groups lobbied intensively in parliament. Finally Turkey's new Civil Code was adopted on 22 November 2001.

It was a radical change to the legal foundations of gender relations and the family. Spouses became equal partners with the same decision-making powers and rights over the children and property acquired during marriage. The new law removes the concept of "illegitimate children" and grants custody of children born out of wedlock to their mother. In the words of justice minister Hikmet Sami Türk (DSP),

"One of the most important particularities of this draft is that in every field equality is stressed. In the union of a marriage, there is, according to the draft, no more family leader. Spouses have the same rights and duties and administer the same responsibilities. Both are responsible for the education of the children."

With these reforms, Turkey had taken an important step towards joining the post-patriarchal world. It was also an important success for the Turkish women's movement. Having started as small groups of urban women meeting in apartments in Istanbul in the early 1980s, the Turkish women's movement had become a serious factor in national politics.

There are two demographic trends that have had a profound impact on the lives of Turkish women: urbanisation and declining population growth. In 1945, only a quarter of Turks lived in cities; by 2000, the proportion was 65 percent. More Turkish women found themselves living in cities, with greater access to education and other modernising influences. Female literacy leapt from 13 percent in 1945 to 81 percent in 2000. Moreover, with fewer children to look after as the number of children born per mother decreased, they began to take an increasing interest in the world outside their homes.

|

Year |

Population (m) |

Urbanisation |

Female literacy |

|

1945 |

18.8 |

25 % |

13% |

|

1960 |

27.8 |

32 % |

25 % |

|

1980 |

44.7 |

44 % |

55 % |

|

2000 |

67.8 |

65 % |

81 % |

These demographic changes introduced new social strata into Turkish society. Turkey's urban population more than doubled in size between 1985 and 2000, resulting in an increase of 24.4 million people in absolute terms. New and rapidly growing suburbs emerged on the outskirts of Istanbul, Ankara and other large cities. They were filled with people who had arrived from their villages with few skills, bringing with them a distinctly conservative and religious outlook. But they also aspired to education, and enjoyed greater opportunities for social mobility than those who remained in the villages. It was this new urban class that created the core constituency for the rise of political Islam, and the electoral success of the Islamist Welfare Party. Women played a key part in this major shift in Turkish politics.

The Istanbul suburb of Umraniye is one of the fastest growing urban areas in the country. Jenny B. White, an American anthropologist who conducted research there throughout the 1990s, portrays the ambivalence of women who were simultaneously resentful of and resigned to the many constraints they faced. One of many conversations she related turned on the subject of women's freedom of movement.

"One woman, her face shadowed by her headscarf and indistinct in the diffuse light, commented: "It's hard to sit alone at home all the time." Another added wistfully, "If only I could travel somewhere." The women immediately muted their complaints by adding firmly that they knew it was right for women to stay at home. They agreed among themselves that unprotected women should be limited in their movements. "One never knows what can happen". They discussed what the Quran said on the subject, although one woman pointed out that, when it came to the severity of the restrictions, it was men's power that determined this, not the Quran."

Several women remarked that they would like to work, but their husbands did not allow it. As the women talked among themselves, the dissatisfaction rose.

"'Men make our lives hard.' 'I wish we had more education.' 'I wish I could work. Earn some money. It's hard when you have to rely on your husband every day to leave money for you. And sometimes he forgets; then what do you do?'"

In one of the strangest paradoxes of Turkish politics, it was the Islamist Party that was instrumental in opening up new opportunities for women in areas such as Umraniye. In the mid-1990s, the Welfare Party developed a very active women's wing. The idea of mobilising women within the party organisation was closely associated with current prime minister Erdogan, who was at the time head of the Welfare Party in Istanbul.

"No other party in Turkey could boast of a similar membership of women. Women of the Welfare Party registered close to a million members in about 6 years… The women's organisations were perhaps the most dynamic unit of the party, visible in all its rallies, meetings and activities."

In Umraniye, nearly half of the 50,000 registered party members were women. Political activism on behalf of the Welfare Party offered women new opportunities – the chance to be trained, work outside the home and exercise a voice on public affairs. In 1999, Yesim Arat talked to 25 women volunteers for the Welfare Party. She was "taken aback by the unmitigated fulfilment these political activists derived from their political work. Without exception, all women interviewed recalled their political activism with pleasure." One activist told Arat: "we all proved something; we gained status."

Yet the political platform of the Welfare Party continued to emphasise that a woman's place was with her home and family. When the party first made it into the national parliament in 1991, it had not a single woman among its 62 MPs. By 1995, it was the largest party in the parliament with 158 deputies, but still with no women represented. Its discourse on women continued to be highly conservative. In 1997, there was a debate among senior party leaders as to whether it was proper to shake hands with a woman. Many of its leaders held to the view that women's issues were best solved by a return to the asri saadet, or age of felicity – namely, by the rules and mores from the time of the Prophet and his immediate successors. Jenny B. White comments on the differences in outlook between men and women Welfare activists.

"Women were interested in the means by which the Islamist movement could allow them to challenge the status quo; men envisioned an ideal in which women were wives, mothers and homemakers."

Attitudes towards the tessetur, or Islamic clothing (headscarf and overcoat), perfectly illustrated this tension. Islamist men saw the headscarf as necessary to protect women and the family honour, by restraining fitne and fesad (the chaos of uncontrolled female sexuality). For religious women with ambitions, however, the headscarf came to symbolise mobility and independence.

A lively debate also sprung up among religious women in the late 1980s, beginning with articles in the daily Zaman were religious women defended an increasingly bold agenda for change. One woman wrote in 1987:

"Why do Muslim men fear women who know and learn? Because it's easy to have power over women who are solely busy with their husbands and are isolated from the outer world and to make them adore oneself. When women are able to receive education and realize themselves, and view their environment with a critical eye, they make men fear."

From the mid-90s onwards, religious women formed associations to pursue women's interests, including the Baskent Women's Platform, the Rainbow Women's Platform and the Organisation for Women's Rights Against Discrimination (AKDER). Selime Sancar from Rainbow explained her position:

"We are a synthesis; secularists have to know their grandmothers wore the hijab, and Islamists must remember that part of Turkey is in Europe and the country has been Westernized ever since the sultans brought Europeans here."

Liberal feminists noted the paradox of Islamic women's activism. Sirin Tekeli wrote in 1992:

"The most unexpected impact of the feminist movement was on fundamentalist Islamic women. While they opposed feminism mainly because feminist ideas were inspired by the materialist values of the Western world, many of them were in fact acting in a feminist spirit when they fought to have access to universities and thereby to gain a place in society as educated professional women without having to lose their identity, symbolised by the veil."

Religious feminists gained the confidence to challenge mainstream Islamist thinking on its merits. Hidayet Tuksal is a theologian at Ankara University Theology Department, who wears the headscarf. She is also a founder of the Baskent Women's Platform. In her view, "religion has been interpreted differently by different people throughout history, leading to male-dominated interpretations." The Baskent Platform set out to challenge the religious basis of discrimination against women. It gave voice to new attitudes among religious women and young people. According to Tuksal, "Twenty years ago, conservatives were against women working. Even going to university was frowned upon." A combination of economic necessity and the desire for social mobility undermined these traditional values. "Work is no longer an issue. Up to 90 percent of the young men in our circles now want to marry a working woman."

The year 2001 saw the Virtue Party (successor to the Islamist Welfare Party) split apart, to create two new parties. One of them, the Felicity Party, continued to present a strongly traditional view of women. In the view of the Felicity Party, stated clearly in its official party programme, the biggest threat to Turkish society comes from abroad.

"Our families have been destroyed at unprecedented speed in recent years… Precautions need to be taken to protect our nation and social structure from the illness of the nuclear family which foreign forces try to inject into us via the media and movies."

The other new party, the AKP, offered a strikingly different platform. From the outset, it defined its difference from the traditionalist Islamists by reference to two issues above all: European integration and the position of women in Turkish society. The AKP party programme set out a very different agenda, committing the party to the implementation of all of the CEDAW requirements. Its promises include encouraging women to participate in public life and be active in politics; repealing discriminatory provisions in laws; working with women's NGOs; and "improving social welfare and work conditions in light of the needs of working women".

When the new Civil Code was brought before parliament in 2001, the Felicity Party opposed it strongly. In a speech before the parliamentary assembly, one of its deputies stated:

"Every union absolutely needs a head. Where there is no head, there is anarchy. This reform will not strengthen the family, it will weaken it. The husband is the head of the union."

The newly created AKP took a different position. AKP deputy Mehmet Ali Sahin spoke in favour of the new Civil Code. His main objection was on an issue that the women's associations had raised concerning the lack of retrospective application of rules on the equal division of assets after divorce. Sahin proposed that if couples married before 2002 do not explicitly object, the newly introduced property regime should also apply to them. Women's activists told ESI that they were surprised by this support at the time.

The AKP clearly set out to distance itself from the traditional Islamists. It had 71 founding members in 2001, of whom 12 were women (half with headscarves, and half without). Its official party programme avoided direct reference to Islam, proclaiming adherence to Turkey's secular traditions defined as "the state's impartiality toward every form of religious belief and philosophical conviction."

Of course, it would take more than fine words to convince the sceptics. Many secularists in Turkey remain profoundly sceptical about the AKP and its intentions. How can a party with its electoral base in the conservative heartland of Central Anatolia or Istanbul suburbs like Umraniye be truly committed to the cause of gender equality? What was to come next, however, was some of the most radical changes to the legal status of women in the history of modern Turkey.

The Turkish Penal Code, in force from 1926 until 2004, was the most striking example of the divergence between rhetoric and reality in the Republic of Turkey. Like many of the laws adopted at the time of Ataturk, it was based on a Western European model – in this case, the Italian Penal Code of 1889. This was then adapted to reflect Turkish values and traditions.

In its treatment of sexual crimes, the 1926 Penal Code reflected the belief that women's bodies were the property of men, and that sexual crimes against women were in fact crimes against the honour of the family. It was full of traditional concepts adapted from Arabic: irz (honor or purity), haya (shame), ar (things to be ashamed of). It treated women's sexuality as a threat that needed to be controlled by society.

"The term used for rape is irza gecmek (penetrating one's honour) instead of the common word used for rape in Turkish, tecavuz (violation, attack). The use of the word irza gecmek for rape implies that rape is viewed in the code primarily as a violation of honour, and not as a crime committed against an individual's bodily integrity."

Treating rape as a question of honour carried a number of consequences. First, it decriminalised marital rape: sexual acts within the context of marriage – even if forced – could not be considered a violation of a woman's honour. Second, it exempted a rapist from punishment if he offered to marry his victim – thereby restoring her honour. Even in the case of a woman raped by many men, an offer of marriage from one of them was considered sufficient for charges against all of them to be dropped.

The Penal Code was also extremely lenient to "honour crimes" – that is, crimes committed for the purpose of restoring a family's honour. One provision granted a reduction of seven-eighths to the perpetrators of honour crimes where the victims had been caught in the act of adultery or "illegitimate sexual relations" (including, for women, sex before marriage), or if there was clear evidence that the victim had just completed such an act. The Code also valued single women less than married women. Abducting a single woman could bring three years imprisonment, while abducting a married women carried a minimum of seven years – suggesting that the real 'victim' in the latter case was the husband.

The persistence of these norms past the end of the 20th century was no mere legal anachronism, but reflected values that were embedded in Turkish society, including among its judges and prosecutors. At the same time, as the 20th century came to an end, these values began to be increasingly contested, as demonstrated most dramatically by the public reactions to a number of highly controversial court decisions. In 1987, a judge in the Central Anatolian province of Corum refused to grant divorce to a pregnant woman who had been abused by her husband, citing a Turkish proverb: "Women should never be free of a child in the womb and a whip on the back!" The decision triggered the first public demonstration since the 1980 coup: more than a thousand women took to the streets in the Istanbul district of Kadikoy.

In another court in 1996, a young man who murdered his cousin, Sevda Gok, in the province of Sanliurfa was given a light sentence, following arguments from the prosecution that "the incident was caused by the socio-economic structure of Sanliurfa." The 16-year old girl had been murdered as a result of gossip in the community that she had acted "shamefully". The trial brought the tolerance of the judiciary for these "honour killings" to the top of the national agenda. However, the outcry did not prevent other such judgements. As late as June 2003, a court in the southeast Anatolian province of Mardin acquitted 27 perpetrators, including military officers, accused of raping a young girl. The court found that there was insufficient evidence as to whether the 13-year-old had consented to the acts.

Experiences such as these motivated Turkish women's organisations to mobilise in pursuit of reform. It was the process of European integration that provided them with the political opportunity to make real progress. Reform of the Penal Code was made a condition for the start of EU membership negotiations.

The association Women for Women's Human Rights (WWHR) responded by forming a working group in early 2002 representing academics, NGOs and bar associations to prepare recommendations for the new Penal Code: "to each article pertaining to us we formulated a word-by-word amendment, including a justification to explain our point of view." The association began the process of raising awareness on the issues, through publications, media campaigns and networking across civil society.

Yet to many of these activists, the campaign appeared to grind to halt before it got started, with the landslide victory of the AKP in the elections of November 2002. Many women's organisations saw the AKP, as successor of the Islamist Welfare Party, as fundamentally opposed to their agenda.

"We called an extraordinary meeting after the elections. Some people wanted to drop the whole thing. But after initial differences, the group gained new energy… It might be several decades until the Penal Code was revised again. We thought: 'Let's do it so we can tell our daughters that we at least tried'."

As it happened, the AKP government took up the matter exactly where its predecessors had left off – with a draft prepared for the previous government by an expert group of academics. Senior academics had exercised effective control over the legislative drafting process for many years, irrespective of who was in power. Chief among them was Sulhi Donmezer, a highly respected figure in the legal establishment known as the 'professor of professors'. He had been involved in most criminal law reform initiatives since the 1950s, including the preparation of new criminal procedures after the 1980 coup. It was Donmezer who had been put in charge again in the late 1990s with preparing a new draft Penal Code.

The 1996 CEDAW report on Turkey had concluded that 29 articles in the Penal Code did not conform to the requirements of the Convention. Remarkably, the draft prepared by Donmezer for the government in power from 1999 to 2002 had left all of these provisions intact, except for cosmetic changes. And when the incoming AKP justice minister Cemil Cicek was photographed kissing the hand of Donmezer in 2003, a columnist in Yeni Safak, a daily known to be close to AKP, commented sarcastically:

"This is another one of those scenes that makes Turkey bizarre. (Donmezer) is now positioned, an irony of history, as the head architect of the EU harmonisation efforts. You decide whether we should laugh or cry…"

It was the Donmezer draft that the AKP justice minister first submitted to the 24-member Parliamentary Justice Commission in April/May 2003.

For the WWHR and the women's working group this was the moment to launch a broad-based public campaign by creating a broader coalition of over 30 NGOs: the Platform for the Turkish Penal Code. WWHR circulated a booklet with concrete recommendations to the new set of parliamentarians, and called a meeting with the head of the parliamentary Justice Committee, Koksal Toptan (AKP). Toptan listened in silence to the arguments made by the members of the Platform, leaving some of them despondent. Nonetheless, by June 2003, Toptan announced that the women's objections would be sent to a subcommittee for consideration. He announced his own agreement with the women's call for the criminalisation of marital rape. Toptan also noted the importance of the EU integration process as a motivation:

"Turkey is in the process of EU membership. In this framework important laws and harmonisation packages have been passed. There have been 65 legislative changes. Now this Penal Code draft seriously conflicts with the new harmonisation laws passed. No one should have any doubt that we will bring it to the highest level."

Over the summer of 2003, it became clear that, for the first time, a real public debate on gender equality was underway. Columnists in Yeni Safak reminded the government of its commitment to work with NGOs. On 23 July, columnist Ali Bayramoglu encouraged the government to meet with the women's groups and take their concerns seriously. The next day the columnist published a letter from an academic at Istanbul University, arguing that consultations on the new draft had been too brief, and that feedback had not been taken into consideration. Ali Bayramoglu concluded:

"The important thing is how the Ministry's interaction and participation mechanism works regarding an issue that involves the entire society. This is more important than the Penal Code draft itself."

Justice minister Cemil Cicek telephoned Ali Bayramoglu after the column to emphasise that the government remained open to discussion on the issue. The minister reiterated:

"We are not uncomfortable or feeling insecure due to the criticisms of the Penal Code draft. We would like all kinds of opinions to be related to the commission. The group, under the leadership of Koksal Toptan, will try to do what is necessary as well as possible."

The government was well aware of the extent of scepticism among Turkish women's organisations about its intentions. One of its MPs, Hakki Koylu, explained to ESI:

"When one says AKP, many think of a party coloured by religion. Because AKP was born out of such a party, the MPs are assumed to be all like that, not the kind that would defend women's rights. Whereas those that split from their former party split for a reason – because they did not agree".

By the time the subcommittee on penal code reform started its work, at the end of October 2003, the women's organizations had succeeded in reshaping the debate. As Koksal Toptan acknowledged on national television:

"the women's associations demonstrated exemplary work in terms of how public opinion can be formed. They participated by coming to the commission or sent reports. And they successfully steered public opinion. We have all the reports the women's organizations have sent to the subcommittee members. When we get to the articles they are objecting to, the reports will certainly be paid attention to. We are really going to listen to every segment of society and especially the women for this law".

The subcommittee extended its deliberations for nine months, until June 2004. Its members included three AKP MPs, two from the Republican People's Party (CHP) and three academics. The academics were known as critics of the Donmezer draft and suggested that it be rewritten from first principles. The atmosphere created by the EU integration process played an important role in helping the subcommittee members reach agreement that a fundamental revision was necessary. The press were also given a daily account of the discussions – a very unusual degree of transparency in Turkey.

"During the subcommittee debates, 6 or 7 correspondents would wait at the door. Every day when we got out of the meeting, I would explain what we had done on that day. They would cover it in the papers. And if there were complaints from people, they would also get covered and we would read them. In a way this was a means of interaction with the interested social partners."

AKP member of the subcommittee Bekir Bozdag explains how this motivated the subcommittee.

"We on the subcommittee felt that society was behind us as we were working. Women's organisations, the media, they were all positively following, and this made a difference."

From their offices near Istanbul's Taksim Square, the small WWHR team coordinated an extremely effective campaign. In Ankara another NGO, the Flying Broom, was doing a similar job. Each time there was a breakthrough, they would immediately congratulate the subcommittee members. They also kept EU embassies informed about the debate. Whenever more pressure was needed, they would send faxes and emails or visit the parliament.

"We had months of faxes, press statements and delegations travelling to Ankara, taking members of parliament out to dinner, writing letters of support to the deputies. We were following the inside story through our friends in the national assembly. This allowed us to respond, positively or negatively, as each article was discussed."

Gaye Erbatur, a CHP parliamentarian, was a key ally of the women's organizations throughout the whole process. Although she was not a member of the subcommittee, she devoted almost all of her time to influencing the process.

"I went to the sub-committee meetings every day to figure out what was being discussed. I used the intermissions to discuss issues like virginity tests or rapists marrying their victims with committee members. I was giving them concrete examples, to make them understand how women feel. The debates were very heated."

The public debate on the reform was particularly heated in autumn 2003. In October Dogan Soyaslan, an academic adviser to the Justice Ministry who joined the meetings from time to time, defended an article in the earlier Donmezer draft that allowed rapists to go unpunished if they married their victims. Soyaslan asserted that, in Turkish society, no one else would agree to marry a woman who is not a virgin, and that for the victim to marry her rapist protects her from honour killing. He pointed out,

"There are many forced marriages in Anatolia anyway. Yet these marriages continue. They may marry reluctantly after a rape, but time is a great healer. They will forget. The marriage won't break."

Soyaslan's proposal triggered an uproar in the press, only made worse when, during a televised debate, he confirmed that he could not imagine this paragraph to apply to his own daughter, saying "No, but I'm different, I'm a professor." The debate provoked by his statements continued for many weeks, as the women's Platform used it to highlight the unacceptable philosophy behind the old penal code.

Though it created a lot of noise in the press, Soyaslan's intervention did not impress the subcommittee. "The mandate of the law", chairman Hakki Koylu (AKP) clarified, "is not to alleviate the negative consequences of unacceptable social practices. It is to change them and prevent them with disincentives". The point was also emphasized by Bekir Bozdag (AKP), who said the Penal Code meant to change social customs, not adapt to them:

"When you recall cases you have come across as practitioners, it is clear that the former penal code was one that protected many wrongs. We all knew that. Encouraging a rapist to marry the rape victim does not fit with the basic logic of law."

After nine months of work, the draft was almost entirely rewritten, beginning with a new Article 1 which stated that the purpose of the law was to protect the rights and freedoms of individuals. The draft was returned to the Justice Committee on 30 June 2004, which deliberated on the text until 14 July and then presented it largely unchanged to parliament, where it was finally passed on 26 September 2004.

The outcome was no less than a legal and philosophical revolution for Turkish society. According to Yakin Erturk, an academic and Turkish feminist, "The whole mentality of the Penal Code has changed." One commentator described it as "the widest discussion of issues related to sexuality in Turkey since the foundation of the Turkish republic in 1923." The minister of justice told parliamentarians:

"Turkey is experiencing a deep and silent mentality change. And the most important reflection of this is the Penal Code."

Some 35 articles concerning women and their rights to sexual autonomy were changed. All references to vague patriarchal constructs such as chastity, morality, shame, public customs or decency had been eliminated. The new Penal Code treats sexual crimes as violations of individual women's rights and not as crimes against society, the family or public morality. It criminalises rape in marriage, eliminates sentence reductions for honour killings, ends legal discrimination against non-virgin and unmarried women, criminalises sexual harassment in the workplace and treats sexual assault by members of the security forces as aggravated offences. Provisions on the sexual abuse of children have been amended to remove the possibility of under-age consent.

This was not just a revolution in the legal status of women. It was also a sign of profound changes in Turkish democracy. The entire process was conducted in a highly transparent fashion, with intense debate and inputs from across society.

"This was a turning point in the history of Turkey, as never before has parliament conducted public consultation in the drafting of bills."

Remarkably, this acutely sensitive set of reforms was achieved through cross-party consensus between AKP and CHP. As the minister of justice informed the parliament in September 2004: "In half a century of multiparty life this may be the first time that the Parliament has produced its own draft." He celebrated this as a shift in the traditional confrontational culture of parliamentary politics, marking it as "perhaps the most important achievement of this parliament."

The image of the new Penal Code was tarnished by a last minute attempt by prime minister Erdogan to introduce amendments criminalising adultery. This was presented in some foreign media as a return to the principles of Islamic family law: in fact, it would have been a return to the legal situation that existed from 1926 to 1996 (for men; for women adultery was decriminalised only in 1998). Nor was it an 'Islamist plot': women organisations were shocked to find that the impromptu proposal by the prime minister initially also found support among the opposition CHP. The initiative was, however, a break with the consultative style that had produced the reform and had been praised by the minister of justice. It also failed. Reactions from within Turkey and across Europe were extremely hostile, forcing the prime minister to withdraw the proposal. Not surprisingly, the episode left a sour taste.

Nonetheless, the Penal Code of 2004 represents a profound achievement for the women's movement, the government and the opposition. Unlike the reforms of the 1920s, it was achieved not by authoritarian dictate, but through intense dialogue and the engagement of civil society and the media in the parliamentary process. It was not just a victory for Turkish women, but also for Turkish democracy. With the new Penal Code, Turkey's legislation entered the post-patriarchal era.

Law is a powerful tool for social change, but it is not a magic wand. It needs to be backed up by resources and government initiatives, to raise awareness and empower citizens to use the new legal framework. Even then, it can take many years for the effects to become visible across society.

In the course of this research, ESI came across police statistics for 2005 listing the number of cases of "men depriving a woman of her virginity on the false pretext of promising to marry", a crime that no longer exists. In South East Anatolia, ESI found that judges can still take months to rule on requests for urgent assistance from women under threat of family violence. Across the country, there are still a number of judges and prosecutors unaware of the content of the new laws.

So how far has Turkey really moved towards gender equality? This chapter looks at a range of government initiatives, and their effects on different sections of Turkish society. It makes it clear that legal reform is only the first step on a very long road. It highlights one of the most important policy challenges facing Turkish policy makers: the vast range of cultures and lifestyles, ranging from post-modern to neo-feudal, in one of Europe's largest democracies.

On 30 October 2006, Songul A., a 22-year-old woman living in the small, Kurdish village of Hacikislak in the Ozalp district of Van, not far from the Iranian border, went with her brother to visit a lawyer. Like hundreds of thousands of other girls across rural Turkey, Songul had not been registered by her family at birth. As far as the Turkish state was concerned, she did not exist. She had never been to school and did not know how to read.

Songul had been raped by Huseyin, a neighbour, while her husband Mehmet was away for seasonal work. Bahattin, a relative of Songul's husband, found out about the rape, and had kept Songul tied up in a barn for two days, torturing her. As is usually the case, the woman was seen as the guilty party for violating her husband's honour, rather than as the victim.

The traditional village mechanism for resolving questions of 'honour' sprang into action. An 8-person council of elders was convened to discuss how to prevent a blood feud between the two aşirets (tribes). In Ozalp, as across the region, tribes form the backbone of the social and political structure at the local level. The main issue at stake was how to restore the 'honour' of Songul's husband Mehmet and his family. The council decided that the appropriate solution was to dissolve Songul's marriage and to oblige the 16-year-old daughter of Huseyin, the rapist, to marry Songul's husband Mehmet, through a religious ceremony, as 'compensation'.

Songul returned to her father's house, in Gunyuzu village. However, with Songul pregnant from the rape and gossip about the incident spreading rapidly, Songul's life was increasingly at risk from her own extended family. That was when her brother decided to take her to Ozalp town to visit a lawyer who was known to their family.

The lawyer took them to the state prosecutor in Ozalp town. Songul told the prosecutor the story of her rape, her unwanted pregnancy and the danger she was in for dishonouring her husband and his family. The prosecutor ordered the gendarmerie to bring Huseyin, the alleged rapist, and Bahattin, the relative who had tortured Songul, in for questioning. Rather than taking her under protection however, he sent Songul back to her father's house, warning the family not to hurt her.

The prosecutor came from Afyon in Western Turkey and had only recently been appointed to Ozalp. According to Songul's lawyer, it is common for state officials appointed from other regions to have little understanding of the local tribal structure and its accompanying traditions. The lawyer told ESI that, if he did not have a strong tribe (asiret) of his own behind him, he would not dare take on a case such as Songul's, which places him under threat from the family of the accused.

Zozan Ozgokce, an activist on women's issues in Van, learned about Songul's situation from the media. She was immediately concerned. In an incident only a month earlier in a different part of the province, a state prosecutor had declined to offer protection to a teenage girl who had given birth out of wedlock. Based on assurances from her family, the prosecutor had returned the girl to her family home. Four days later, she was murdered by her own brother.

Fearing that Songul's life was also in danger, Ozgokce turned to the official institutions in Van. Although it was a Sunday, she called several departments in the security apparatus and the provincial director for social services. They said they could not take action without an order from the prosecutor. She could not reach the prosecutor or the provincial governor. As a last resort, Ozgokce contacted Fatih Cekirge, a journalist who she knew was preparing a documentary about honour killings. He was scheduled to appear live on television that evening, and promised to raise the issue. During the show, Cekirge provocatively called on the governor of Van province to do something, stating: "Let us see if the state really exists!" The response was immediate. The same night, both Songul and the daughter of the rapist were taken into protection by the gendarmerie.

The two women are now in a shelter for abused women in a different province. Criminal cases have been brought against Huseyin (for the original rape), the village elders who forced the rapist's under-aged daughter to marry against her will, and against Songul's former husband.

Songul's dramatic story is not an isolated incident. Across Turkey, police figures for honour killings number 1,091 in total between 2000 and 2005. This reflects only the killings that take place in urban settings, under the jurisdiction of the police. A parliamentary report on honor killings admits in 2005 that "comprehensive and systematic research about violence against women has not been carried out" so far.

Violence is a feature of daily life for a large number of women in Van. In surveys, 82 percent of women are victims of violence 'often' or 'very often'. Fifty-three percent of women report violence from their husband, and 30 percent report violence from their mother-in-law. The triggering events for domestic violence can range from leaving home without permission or returning home late, to neglecting household chores or refusing marital sex.

The high rate of violence against women in Van has a distinct cultural, socio-economic and political context. Lying on the Iranian border in the far east of Anatolia, Van is one of Turkey's poorest provinces. It has experienced dramatic social and economic change. Over the past decades, it has received major migration from people displaced by the armed conflict between the Turkish military and the terrorist PKK in Turkey's southeast, swelling its population by nearly a quarter. As a result, even in the urban areas, village lifestyles are prevalent. Cut off from their land, many of the immigrants depend on casual or seasonal work. Van's industrial zone, set up in 1998, has only 27 active businesses; the remaining 73 plots are empty or under construction. Employment in industry in this province inhabited by more than 1 million people is less than 7,000. Per capita income is only 55€ per month. By any measure of socio-economic development in Turkey, Van ranks near the bottom of the list.

In the face of such deeply rooted poverty, large families continue to be a key mechanism for social protection and control. Households in Van average 7.4 members, with most women kept at home to look after children and the elderly and to perform domestic work. Girls marry at a very young age – around half of them between 16 and 20 – and often within the extended family.

Sixteen percent of men and nearly half the women in the province are illiterate. Although there is a university in Van only a third of the students continue from primary on to secondary school. These factors – high dependence on subsistence farming, sudden and very recent urbanisation, low incomes, large families, poor education outcomes – combine to entrench a deeply conservative society, in which traditional views of a woman's place and a man's honour prevail, among women and men alike.

Yet even in Van, there are cautious signs of change, as we can see from Songul's story. The influence of an activist like Zozan Ozgokce is one new factor. On 9 April 2004, Ozgokce and six other women formally established VAKAD (Van Kadin Dernegi) [Van Women's Association] to offer support to victims of family violence. With ten staff and a network of 30 volunteers, they provide advice and training courses. One of their goals is to help Kurdish women overcome their reluctance to deal with state institutions (many Kurdish women in the region do not speak Turkish). One study by WWHR found that 57 percent of women in Eastern Turkey had experienced physical violence, but only 1.2 percent had notified the police and 0.2 percent had filed a complaint.

VAKAD is not the only such organization in Van today. Yakakop – the first women's NGO to be established in Van town – organises training courses for women on health issues and basic skills. "No woman ever left the house without a man from the family"', Gulmay Ertunen remembers from her own time as a young bride. Now she runs Yakakop. Yakakop began with a small World Bank grant. Ertunen struggled for months to persuade husbands to permit their wives to leave home alone to attend the courses. It took the intervention of the local imam to reassure the men that Yakakop was an 'honourable' organisation.

The political environment for these activities is also difficult. Zozan Ozgokce explains that some women's organisations in Ankara and Istanbul resist her attempts to raise the specifically Kurdish cultural context for gender inequality. "They tell me not to create a hierarchy of victimisation, arguing that 'we are all women and need to struggle together'." Yet from within Van, VAKAD is at times denounced as a missionary agency or agent of foreign interests, owing to the funds it receives from international sources, including the European Union. Upon her return from a CEDAW meeting in New York, word spread through the town that Ozgokce was carrying bibles in her suitcase. In fact, they were brochures by international women's organisations. Conservative circles attack her for undermining families and for generating negative publicity for the town. She has received death threats from the families of the women she supports.

The reaction of public institutions to Songul's case is also an indication of change. It illustrates how long it takes for legal and institutional reforms to filter down to the local level. Law 4320 on domestic violence, introduced in 1998, enables prosecutors to seek protection orders for women from abusive or violent husbands, including the provision of shelter for those who cannot remain in their homes. However, as Songul's lawyer told ESI:

"A request for protection is not something that is done here… Even if I lose the case against these men, it is already a victory. Everyone has heard now that the state protects women under these circumstances."

There are few applications from women in rural areas, according to local prosecutors, because transport and communications are so poor. Prosecutors are often reluctant to use their power to intervene, fearing that they may trigger an escalation of violence. The informal power of tribes remains strong. There are also doubts as to whether the Family Protection law applies to the couples (estimates go up to 20 percent) married only through religious ceremonies (imam nikahi), which are not recognised by the courts. WWHR found that in 1996 11 percent of women lived in polygamous relationships – officially banned since 1926. For many of these women, even the best law is simply out of their reach.

Poor coordination between state institutions and the absence of a suitable shelter were additional problems. Now a shelter is being established. The governorate has also established an inter-agency Monitoring Committee to coordinate action among institutions for protecting women subject to violence. The first Family Court opened in Van in September 2005.

These actions are in part a response to central government initiatives, following a directive issued by the prime minister in 2006 on "Precautions to be taken against violence towards children and women, and customs and honour killings". It was based on the findings of a 12-member special parliamentary commission set up in May 2005 under the leadership of AKP deputy Fatma Sahin. It calls for a broad national strategy to enhance the status of women in Turkey and combat violence, and includes a reference to the need for positive discrimination measures until equality between men and women is achieved. Ensuring that these initiatives are effective in a place like Van will require a great deal more effort.

Across the other side of Anatolia, a long way from Van geographically, culturally and economically, lies Kadikoy, one of the most prosperous districts of Istanbul. It is a favourite spot for the country's executive class. On Bagdat Street, international brands vie for wealthy customers, and outdoor cafés are filled with young professionals. There are exclusive sailing clubs along the shores of the Marmara Sea. Where Van is isolated, Kadikoy is a transport hub, connected by boat, train and bus to every corner of Turkey. It is home to an alternative music scene, and Fenerbahce football club, one of Istanbul's big three. It has a population of 660,000, more than some EU member states. The municipal motto is: "It is a privilege to live in Kadikoy."

So how is life for the women of Kadikoy in 2007? 95 percent of Kadikoy's residents are literate, and one in five is a university graduate. Female employment has become increasingly common, and more women are achieving professional and managerial positions. Many women are choosing to delay marriage and childbirth, and the average household size has fallen to 2.4. Exposed to wider European influences, the women of Kadikoy have been at the forefront of Turkey's women's movement, forming a large number of voluntary associations. Inci Bespinar, Kadikoy's female deputy mayor, explains:

"Kadikoy provided the environment for women to raise questions about their place in society. The women had sufficient economic means and time at their hand to think about these things. They also had the culture and foreign languages to be linked to the outer world. Kadikoy was also integrated with women's organizations abroad. We would wait in anticipation for them to come from trips abroad to read about their new insights. Time, money and culture… these are the three main ingredients."

Both the municipal authorities (run since 1994 by a CHP mayor) and the private sector have responded to the rising expectations (and spending power) of middle-class families. The first pre-school opened in 1989/90. There are now five crèches and 38 private pre-schools. The social stigma attached to putting the elderly into professional care is also fading slowly, although some see this as an unwelcome intrusion of Western values. There are now 17 homes for the elderly (5 state and 12 private). Another controversial social trend is the rising divorce rate, albeit from very low levels. There are five family courts operating in Kadikoy, all opened since January 2003 as a result of EU-inspired judicial reforms. The new courts are well equipped by any standards, with psychologists, social workers and public-education specialists. Few of the 157 family courts elsewhere in Turkey have managed to fill these positions.

Yet the rise of the middle-class woman is only part of the story of Kadikoy. Like Van, its population has grown rapidly in recent decades, from 241,000 in 1970 to over 660,000 in 2000. Growth has been driven almost entirely by urbanisation, with 60 percent of the population born outside of Istanbul. The poorer immigrants live in shanty towns stretching south along the E5 motorway, making up around 10 percent of Kadikoy's population. Largely illiterate, with poor employment prospects and dependent on social assistance, the women in these communities face many social problems. So how effectively does a wealthy Turkish municipality deal with these kinds of problems?

Inci Bespinar, Kadikoy's deputy mayor, embodies the vitality of Kadikoy women. In one corner of her spacious office, a group of women are planning a forthcoming cultural project, while her phone is ringing constantly. Outside her office, a team of municipal civil servants are trying to handle a long queue of women and men dropping into her office to ask for assistance.

Bespinar's own life is a reflection of improvements in the position of women in Istanbul in the past generation. The eldest daughter of an old Istanbul family she went to study economics in Ankara, encouraged by her father. Kicked out of university for participating in protests she returned to Istanbul. In 1973 and 1975 she gave birth to her two daughters. At first her mother-in-law looked after them, but when she died in 1976 Bespinar had to stay at home. She was offered a job in 1977, which she could not take up. The first municipal pre-school only opened up in 1989.