A morality tale – Part II

For Part I please go here: Why-macedonia-is-not-finland-rankings-and-the-pisa-gap

At its heart, the Finnish development story is a story about reallocating time and attention. It is a story about focus, about how – over time – incremental change can lead to dramatic transformations. Finland was not always the success story it is today. This success was the result of a national policy vision. It is the story of an unlikely success.

This is certainly the consistent theme in all modern history books on Finland. David Kirby opens his Concise History of Finland as follows:

“Finland can fairly lay claim to have been one of the big success stories of the modern age.”

Then he adds:

“The transformation of what less than a century ago was a poor agrarian land on the northern periphery of Europe into one of the most prosperous states of the European Union today is a remarkable story, but it is by no means an uneventful one.”

Fred Singleton starts his Short History of Finland like this:

“Today it is one of the most prosperous, socially progressive, stable and peace loving nations on earth.”

Then he adds:

“The homeland of the Finns is not, at first glance, a likely base for such a successful state.”

Why was success unlikely here? Most accounts begin with nature, the epic theme of wresting a living from the soil in Europe’s northernmost country, a third of which lies within the Arctic Circle. Fred Singleton notes that throughout history “there was little to attract conquerors or traders to this remote land of lakes and forests with its harsh winters.”

In other words: natural endowments do not explain why Macedonia is worse-off today than Finland. Nor does climate. Finland has long, dark and cold winters. Then the sea – across which 90 per cent of exports are transported today – freezes over (necessitating ice-breakers to permit traffic). This climate poses severe limitations for agriculture. In the north of the country the snow covers the ground for up to 220 days.

Nor is it a matter of raw materials. Compared to its neighbors, Norway and Russia, Finland has limited natural resources, aside from pine and spruce forests that cover half the territory. Due to the cold, everything is more expensive here, from building a transport network to heating factories. In 1918 Finland was still primarily an agricultural society. Half of its GDP derived from agriculture. Most non-agricultural activities focused on timber and pulp.

How about geopolitics: are Balkan nations not uniquely cursed by their geography? In fact, the geopolitics of the European North in the 20th century was not for the faint-hearted. For centuries control of Southern Finland has been central to the great power struggles in the North: between Sweden and Russia until the early 19th century; between Germany and the Soviet Union in the 20th. (During the Crimean war in the 1850s Helsinki and other coastal towns of Finland, then within the Czarist Empire, were bombed by the English fleet).

Finns also faced another challenge familiar to Balkan nations: linguistic conflict. For centuries, well into the modern era, elites in Finland spoke Swedish. Finland’s iconic 20th century hero, General Gustaf Mannerheim – the Ataturk of Finland, voted the most important Finn ever in a recent survey – spoke much better Swedish than Finnish. It took a while for Finnish culture to be recognised even by its closest and friendliest neighbor, Sweden. As the editor of Dagens Nyheter, Sweden’s leading daily, put it in the 19th century:

“it took centuries for Swedish culture to lead the Finnish people, whom it had taken under its care and protection, to civilization, self-esteem and independence.”

Finnish only obtained equal status with Swedish in the administration in 1863. When a baron spoke in Finnish in the estate of nobility for the first time in 1894 (!) it caused a furor. In 1880 less than one third of grammar schools were in Finnish. By 1900 it was still only two thirds.

The reality of Finland’s recent economic past is one of deep poverty. There were truly disastrous famines in the 1860s – hundreds of thousands died then, Finland suffered “shockingly high mortality rates” (Kirby). In the 1860s, a slogan was “Nature seems to cry out to our people: Emigrate or Die!” Early 20th century Finland was home to many tenant farmers and landless laborers. In 1910 “over half of the holdings were smaller than the five hectares deemed by the 1900 Senate commission on land tenure to be the minimum size for subsistence.” (Kirby). This fed political tensions, with rising frustrations, and “a large number of poor Finnish peasants were prepared to resort to desperate measures against the richer farmers in order to wreak vengeance upon those who had oppressed them.” It also lead to civil war immediately after independence in 1917.

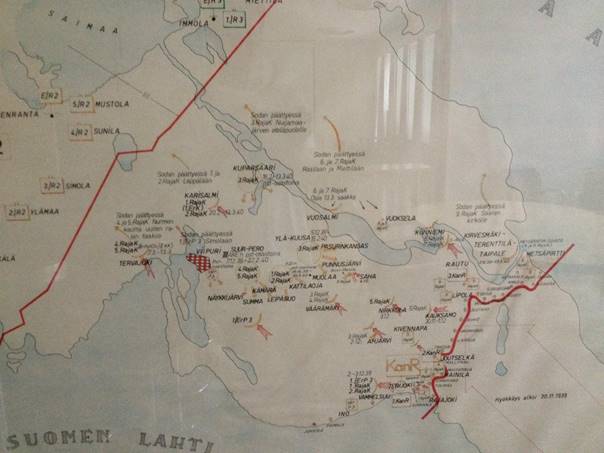

The history of early Finnish democracy was conflict-ridden. Once independent from the Russian Empire Finland plunged immediately into civil war between Reds and Whites. The outcome was only determined when German troops reached Helsinki. Invaded by Russia in 1939, Finland was forced to cede territory to the mighty neighbor, and to accept the displacement of four hundred thousand Finns as refugees from Karelia. Then there was a disastrous alliance of Finnish democracy with Nazi-Germany to fight a “holy war” (Mannerheim) to retake Karelia. A doomed effort to hold on to Karelia followed. This led to another loss in 1944 to Soviet troops. Another war against German troops in Lapland followed. In the first half of the 20th century, Finns had thus fought in three wars.

After World War II, Finland had to pay huge reparations to the Soviet Union. Post-war Finland was forced to resettle hundreds of thousands, forced to pay huge reparations to the Soviet Union, forced to abandon a peninsula outside Helsinki to the Soviets until the 1950s. It also stayed out of the Marshall Plan and did not receive US aid. It did not even join the Council of Europe until May 1989!

It was only after this ordeal that the transformation of the (seemingly) ugly duckling into the majestic swan takes place. For after World War II something crucial happened. Finland’s leaders abandoned all greater geopolitical aspirations. They gave up on what Singleton called the “Concept of Greater Finland.” Their leaders now defined the Finnish national character through pragmatism. Mannerheim, the general who now became president, led the way:

“Mannerheim realized that Finland could no longer pose as a bastion for Christian civilization against the barbarian hordes of bolshevism. There was no more talk of crusades against the hereditary enemy. Instead there was a sober appreciation that, if Finland was to survive and prosper as a democratic society, a way must be found to live at peace with the giant eastern neighbor.”

Singleton described this turning point as turning away from romantic nationalism:

Finland had to “face soberly and without illusions the bleak truth that the only road to survival leads in the opposite direction from that which had previously been followed. The romantic nationalism of the nineteenth century which had played a vital part in the formation of the Finnish nation could offer no comfort or support in the world of the mid twentieth century.”

Now Finnish elites focused on growth, despite an uncertain geopolitical neighborhood. The country systematically developed its comparative advantages, from designing household appliances to developing forestry products. Singleton notes:

“Emerson might have been writing about Finland when he said ‘If a man can write a better book, preach a better sermon, or make a better mouse-trap than his neighbor, though he builds his house in the woods, the world will make a beaten path to his door.’ Finland’s ‘better mouse-traps’ include ice-breakers, glassware, ceramics, pharmaceutical products, high-quality textiles, pre-fabricated houses, sports equipment, electronics, cruise liners, and a whole host of other specialized products …”

Crucially one of these “better mousetraps” was the Finnish education system itself. In 1952 nine out of ten Finns had only completed 7-9 years of basic education. As late as the early 1970 “for three-quarters of adult Finns, basic school was the only completed form of education.” Finland was a net exporter of labor until the 1980s with some 750,000 people going to work in Sweden between 1945 and 1994, turning Finns into the largest migrant community there.

Educating everyone as best as possible, borrowing the best ideas for this from others, motivating educators … all this now came to be seen as central to Finnish identity. Classical Finnish literature was interpreted in this light, the Finnish national story told as a story of the triumph of education over poverty, mind over matter. Primary school teachers came to be seen as standard bearers of national ideals. It is a narrative that resembles a morality tale. The Finnish national movement in the 19th century was interpreted as being centrally about education. The stories in the Finnish national epic Kalevala were seen to celebrate “mental agility”. Finland’s first novel – Seven Brothers – was read as a story about the value of education.

One symbolic story of un-heroic and life-improving creativity is that of the teacher Maiju Gebhard. She calculated that Finnish housewives spent 30,000 hours in life washing and drying dishes. That was equivalent to 3,5 years of life. So she invented something uniquely Finnish: the astiankuivauskaappi (or dish draining closet – see photo) installed today in almost every Finnish kitchen (but in no other countries). This was then “developed in the Finnish Association for Work Efficiency from 1944 to 1945. The Finnish Invention Foundation has named it as one of the most important Finnish inventions of the millennium.”

Creativity and daily life

An invention by teacher Maiju Gebhard: the astiankuivauskaappi (or dish draining closet), still found today in every Finnish household.

It is a riveting rags-to-riches story. It is like the children’s story of an ordinary person, dismissed by everyone as of little account, who suddenly steps to the center of the stage and turns out to be exceptional. The story of the obscure squire who, without effort, pulls the sword out of the mighty stone in the churchyard; the ungainly duckling, ridiculed for its clumsiness, who becomes a swan; the story of Clark Kent, the bespectacled reporter, who suddenly transforms into ‘Superman’.

I still do not know much about Finland, but I do feel that this is a story worth telling in the Balkans. In this post-heroic narrative of a small country, “education” came to be regarded as the secret behind a national transformation, the equivalent to the tin of spinach that transforms Popeye, the ineffectual sailor; or the magic lantern that helped the little orphan Aladdin rise up in life.

And there is the central lesson, which that has nothing to do with fairy tales. Tinkering with mousetraps, saving time and effort through simple inventions in daily life, designing elegant ceramics for household, thinking through all aspects of the national education system all takes time. Attention. Focus. By leaders, by intellectuals, by ordinary people.

Skopje, 2011

Now look at the Western Balkans in the early 21st century through this prism.

Look at the issues that obsess leaders in Skopje, the great prestige projects they have focused their time and attention on. (Yes, they are in some ways just copying their neighbors … but modern Greece is no Finland either, and for a reason).

Look at the issues that intellectuals, academics and politicians most like to discuss in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is rarely about how to design better mousetraps, but usually about how – if there would be a magic fairy – a new constitution would suddenly appear and all would be well.

Look at leaders’ allocation of time, energy and money in Kosovo. How many monuments to warriors have they built … and how many libraries to instill the love of books in the next generation?

Perhaps we can now answer the question of why Macedonia is not Finland. It lacks the national narratives that celebrate pragmatism, ordinary people, education and teachers as the national heroes of the future. Macedonia has not followed where Finland led one century ago in the field of women’s empowerment. It is not turning away from romantic nationalism but celebrates it.

One day leaders will emerge in the Western Balkans who take pride in building museums of science and design instead of temples to dead warriors and bandits. But when this will happen remains to be seen.

Finnish impressions – a post-heroic nation

Reminder of a complex neighbourhood: the Russian church in Helsinki

A national trauma and its consequences – losing Eastern Karelia, twice, to Russia in the 20th century

Gustav Mannerheim. His life reflects his country’s dramatic 20th century history. From a Swedish-Finnish family, growing up in the Czarist Empire, he volunteered for service in the Russian-Japanese war. He then became a spy in the “Great Game” in Asia. Following the revolution in 1917 he returned to Finland and led the Whites in the civil war against Finnish revolutionaries. He came out of retirement to fight in the Winter War in 1939. He was decorated by his own country, by the allies (French Legion d’honneur), by neutral Sweden and by the Nazis (receiving the Iron Cross; the surprise guest at his 75th birthday in Finland was Hitler). He then ended his political career as president of democratic Finland.

Rumeli Observer in Helsinki