Sometimes a speech really needs no further comment. Here is Viktor Orban, the prime minister of Hungary, speaking on 15 March 2016, the Hungarian National day. All I did is to highlight some passages in old. For the rest, please trust me: this is worth reading.

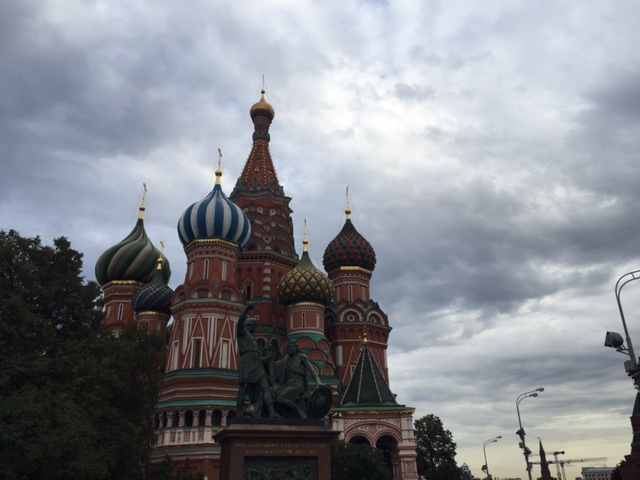

15 March 2015, Budapest – speech on the occasion of Hungary’s national holiday

“Salutations to you, Hungarian freedom, on this the day you are born!”

Ladies and Gentlemen, Compatriots, Hungarians around the World,

With a cockade sewn by Júlia Szendrey pinned to his chest, a volume of poems in his pocket, and the still thrilling experience of the Revolution in his head, these are the words with which the poet Sándor Petőfi welcomed the fifteenth of March in his journal. Salutations to you, Hungarian freedom, on this the day you are born! And today also, one hundred and sixty-eight years later, it is with unfettered joy, the optimism of early spring, high hopes and an elevated spirit that across the Carpathian Basin we celebrate – from Beregszász to Szabadka, from Rimaszombat to Kézdivásárhely: every Hungarian with one heart, one soul and one will.

Just as then in the decisive battles of the Freedom Fight, now also Hungarian hearts are cheered by the fact that we have with us a Polish legion. I welcome the spirited successors of General Bem: we welcome the sons of the Polish nation. As always throughout our shared thousand-year history, now, too, we are standing by you in the battle you are fighting for your country’s freedom and independence. We are with you, and we send this message to Brussels: more respect to the Polish people, more respect to Poland! Greetings to you. It is a sign of the shared fate of Poland and Hungary that another glorious revolution of ours – that of 1956 – was born between the Bem Statue and Kossuth tér in Budapest. It rose up with the unstoppable force of our glorious ancestors, and by the evening it had dragged the Soviet generalissimo out of his boots.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

By nature, Hungarians stand up for what is right when the need arises. What is more, they fight for it if needs be, but do not seek out trouble for its own sake. They know that they can often achieve more through patience than through sabre-rattling. This is why those like us are rarely given to revolutions. We have only gone down that path twice in one hundred and seventy years. When we did follow that path, we had reason to do so: we felt that our lungs would burst if we could not breathe in freedom. We threw ourselves into it, and once we had started a revolution, we did so in style. Modern European history has preserved both Hungarian revolutions among the glorious memories of the world: two blazing stars, two national uprisings bursting forth in 1848 and 1956 from Hungarian aspirations and Hungarian interests. Glory to the heroes, honour to the brave. Chroniclers have also recorded the revolution of 1918–19, but the memories of that period are not preserved on the pages of glory; indeed, not only are those memories written on different pages, but they appear in a different volume altogether. The 1918–19 revolution can be found in the volume devoted to Bolshevik anti-Hungarian subversions launched in the service of foreign interests and foreign ambitions; it features under the heading “appalling examples of intellectual and political degeneracy”. Yes, we Hungarians have two revolutionary traditions: one leads from 1848, through 1956 and the fall of communism, all the way to the Fundamental Law and the current constitutional order; the bloodline of the other tradition leads from Jacobin European ancestors, through 1919, to communism after World War II and the Soviet era in Hungary. Life in Hungary today is a creation of the spiritual heirs and offspring of the ’48 and ’56 revolutions. Today, as then, the heartbeat of this revolutionary tradition moves and guides the nation’s political, economic and spiritual life: equality before the law, responsible government, a national bank, the sharing of burdens, respect for human dignity and the unification of the nation. Today, as then, the ideals of ’48 and ’56 are the pulse driving the life force of the nation, and the intellectual and spiritual blood flow of the Hungarian people. Let us give thanks that this may be so, let us give thanks that finally the Lord of History has led us onto this path. Soli Deo gloria!

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Not even the uplifting mood of a celebration day can let us forget that the tradition of 1919, too, is still with us – though fortunately its pulse is just a faint flicker. Yet at times it can make quite a noise. But without a host animal, its days are numbered. It is in need of another delivery of aid from abroad in the form of a major intellectual and political infusion; unless it receives this, then after its leaves and branches have withered, its roots will also dry up in the Hungarian motherland’s soil, which is hostile to internationalism. And this is all well and good.

A decent person who raises their children and works hard to build the course of their life does not usually end up as a revolutionary. The right-thinking person who stands on their own two feet and has control over their future knows that upheavals and the sudden upending of the ordinary course of life rarely ends well. The person of goodwill who seeks a life of serene and peaceful progress knows that trying to take two steps at once leads to you tripping over your own legs, and instead of moving forward, you will land flat on your face. And yet these right-thinking people of goodwill, these upstanding citizens of Pest instantly rallied to the call of our revolutions, marching at the front, right behind the university students. They formed the backbone of the revolutions and freedom fights, and they were to pay with their own blood for the honour of the Hungarian people. Every revolution is like the people who make it. On the committee which oversaw order during the 15 March revolution, in the shadow of the colossal figures of Petőfi and Vasvári, we find the furrier Máté Gyurkovics, and the button-maker György Molnár. Our revolutions were led by respectable citizens, military officers, lawyers, writers, doctors, engineers, honest tradespeople, farmers and workers with a sense of national duty: Hungarians who embodied the nation’s best aspects, our homeland’s very best. Hungarian revolutionaries are not warriors for hare-brained ideologies, deranged utopias or demented, unsolicited plans for world happiness; in Pest you find no traces of the illusory visions of quack philosophers or the raging resentment of failed intellectuals. The revolutionaries of 1848 did not want to salvage stones from the ruins of absolutist oppression in order to build a temple to yet another tyranny; therefore the Hungarian revolution’s songs were not written in honour of the steel blade of the guillotine or the rope of the gallows. Our songs are not sung by lynch mobs or execution-thirsty crowds; the Pest revolution is not a hymn to chaos, revenge, or butchery. The 1848 Revolution is a solemn and dignified moment in our history, when the wounds of the glorious Hungarian nation opened once again. Springing from constitutional roots, it demanded the granting and return of the rights seized from and denied to the nation. It is exhilarating, but sober; ecstatic but practical; glorious, but temperate. It is Hungarian to the core.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Three weeks before his death in battle, in his last letter to János Arany, Sándor Petőfi asked the following question: “So what are you going to do?” When we, his modern descendants, read this, it is as if he is asking us the same question. So what are you going to do? How will you make use of your inheritance? Are the Hungarian people still worthy of their ancestors’ reputation? Do you know the law of the Hungarians of old – that whatever you do should not only be measured by its utility, but also by universal standards? This is because your deeds must pass the test not only here, but also in eternity.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

We have our inheritance, the Hungarian people still exist, Buda still stands, we are who we were, and we shall be who we are. Our reputation travels far and wide; clever people and intelligent peoples acknowledge the Hungarians. We adhere to the ancient law, and also measure our deeds by universal standards. We teach our children that their horizon should be eternity. Whether we shall succeed, whether finally we see the building of a homeland which is free, independent, worthy and respected the world over – one which was raised high by our forebears from 1848, and for which they sacrificed their lives – we cannot yet know. We do know, however, that the current European constellation is an unstable one, and so we have some testing times ahead. The times in which we live press us with this question, which is like a hussar’s sabre held to our chest: “Shall we live in slavery or in freedom?” The destiny of the Hungarians has become intertwined with that of Europe’s nations, and has grown to be so much a part of the union that today not a single people – including the Hungarian people – can be free if Europe is not free. And today Europe is as fragile, weak and sickly as a flower being eaten away by a hidden worm. Today, one hundred and sixty-eight years after the great freedom fights of its peoples, Europe – our common home – is not free.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Europe is not free, because freedom begins with speaking the truth. In Europe today it is forbidden to speak the truth. A muzzle is a muzzle – even if it is made of silk. It is forbidden to say that today we are not witnessing the arrival of refugees, but a Europe being threatened by mass migration. It is forbidden to say that tens of millions are ready to set out in our direction. It is forbidden to say that immigration brings crime and terrorism to our countries. It is forbidden to say that the masses of people coming from different civilisations pose a threat to our way of life, our culture, our customs, and our Christian traditions. It is forbidden to say that, instead of integrating, those who arrived here earlier have built a world of their own, with their own laws and ideals, which is forcing apart the thousand-year-old structure of Europe. It is forbidden to say that this is not accidental and not a chain of unintentional consequences, but a planned, orchestrated campaign, a mass of people directed towards us. It is forbidden to say that in Brussels they are constructing schemes to transport foreigners here as quickly as possible and to settle them here among us. It is forbidden to say that the purpose of settling these people here is to redraw the religious and cultural map of Europe and to reconfigure its ethnic foundations, thereby eliminating nation states, which are the last obstacle to the international movement. It is forbidden to say that Brussels is stealthily devouring ever more slices of our national sovereignty, and that in Brussels today many are working on a plan for a United States of Europe, for which no one has ever given authorisation.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Today’s enemies of freedom are cut from a different cloth than the royal and imperial rulers of old, or those who ran the Soviet system; they use a different set of tools to force us into submission. Today they do not imprison us, they do not transport us to camps, and they do not send in tanks to occupy countries loyal to freedom. Today the international media’s artillery bombardments, denunciations, threats and blackmail are enough – or rather have been enough so far. The peoples of Europe are slowly awakening, they are regrouping, and will soon regain ground. Europe’s beams laid on the suppression of truth are creaking and cracking. The peoples of Europe may have finally understood that their future is at stake: not only are their prosperity, their comfort and their jobs at stake, but their very security and the peaceful order of their lives are in danger. The peoples of Europe, who have been slumbering in abundance and prosperity, have finally understood that the principles of life upon which we built Europe are in mortal danger. Europe is a community of Christian, free and independent nations; it is the equality of men and women, fair competition and solidarity, pride and humility, justice and mercy.

This danger is not now threatening us as wars and natural disasters do, which take the ground from under our feet in an instant. Mass migration is like a slow and steady current of water which washes away the shore. It appears in the guise of humanitarian action, but its true nature is the occupation of territory; and their gain in territory is our loss of territory. Hordes of implacable human rights warriors feel an unquenchable desire to lecture and accuse us. It is claimed that we are xenophobic and hostile, but the truth is that the history of our nation is also one of inclusion and the intertwining of cultures. Those who have sought to come here as new family members, as allies or as displaced persons fearing for their lives have been let in to make a new home for themselves. But those who have come here with the intention of changing our country and shaping our nation in their own image, those who have come with violence and against our will, have always been met with resistance.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

At first, they are only talking about a few hundred, a thousand or two thousand relocated people. But not a single responsible European leader would dare to swear under oath that this couple of thousand will not eventually increase to tens or hundreds of thousands. If we want to stop this mass migration, we must first of all curb Brussels. The main danger to Europe’s future does not come from those who want to come here, but from Brussels’ fanatics of internationalism. We cannot allow Brussels to place itself above the law. We shall not allow it to force upon us the bitter fruit of its cosmopolitan immigration policy. We shall not import to Hungary crime, terrorism, homophobia and synagogue-burning anti-Semitism. There shall be no urban districts beyond the reach of the law, there shall be no mass disorder or immigrant riots here, and there shall be no gangs hunting down our women and daughters. We shall not allow others to tell us whom we can let into our home and country, whom we will live alongside, and whom we will share our country with. We know how these things go. First we allow them to tell us whom we must take in, then they force us to serve foreigners in our country. In the end we find ourselves being told to pack up and leave our own land. Therefore we reject the forced resettlement scheme, and we shall tolerate neither blackmail, nor threats.

The time has come to ring the warning bell. The time has come for opposition and resistance. The time has come to gather allies to us. The time has come to raise the flag of proud nations. The time has come to prevent the destruction of Europe, and to save the future of Europe. To this end, regardless of party affiliation, we call on every citizen of Hungary to unite, and we call on every European nation to unite. The leaders and citizens of Europe must no longer live in two separate worlds. We must restore the unity of Europe. We the peoples of Europe cannot be free individually if we are not free together. If we unite our forces, we shall succeed; if we pull in different directions, we shall fail. Together we are strength, disunited we are weakness. Either together, or not at all – today this is the law.

Ladies and Gentlemen,

In 1848 it was written in the book of fate that nothing could be done against the Habsburg Empire. If then we had resigned ourselves to that outcome, our fate would have been sealed and the German sea would have swallowed up the Hungarians. In 1956 it was written in the book of fate that we were to remain an occupied and sovietised country until patriotism was extinguished in the very last Hungarian. If then we had resigned ourselves to that outcome, our fate would have been sealed, and the Soviet sea would have swallowed up the Hungarians. Today it is written in the book of fate that hidden, faceless world powers will eliminate everything that is unique, autonomous, age-old and national. They will blend cultures, religions and populations, until our many-faceted and proud Europe will finally become bloodless and docile. And if we resign ourselves to this outcome, our fate will be sealed, and we will be swallowed up in the enormous belly of the United States of Europe. The task which awaits the Hungarian people, the nations of Central Europe and the other European nations which have not yet lost all common sense is to defeat, rewrite and transform the fate intended for us. We Hungarians and Poles know how to do this. We have been taught that only if you are brave enough do you look danger in the face. We must therefore drag the ancient virtue of courage out from under the silt of oblivion. First of all we must put steel in our spines, and we must clearly answer the foremost, the single most important question determining our fate with a voice so loud so that it can be heard far and wide. The question upon which the future of Europe stands or falls is this: “Shall we live in slavery or in freedom?” That is the question – give your answer!

Go for it Hungary, go for it Hungarians!