Cutting the Visa Knot - How Turks can travel freely to Europe

Visa liberalisation has been a crucial element in the EU's relations with Romania, Serbia and Albania. Yet until recently it had not even appeared on the agenda of talks between Brussels and Ankara. Then on 21 June 2012, the Council invited the Commission to establish a dialogue with Turkey aimed at visa liberalisation. Almost a year has passed since these Council conclusions. The dialogue on visa liberalisation has yet to begin.

From the European Commission's point of view, what needs to happen next is obvious. Turkey must accept what the EU Council specified as the single most important condition for a visa liberalisation dialogue: signing a readmission agreement with the EU. Then the Commission would hand over to Turkey a list of official requirements for visa-free travel, known as the "roadmap".

Turkish officials have misgivings about the implementation of the readmission agreement and its costs, as well as about specific requirements in the roadmap. The EU has not resisted the temptation to model the visa liberalisation process after EU accession talks. However, the EU-Turkey visa dialogue cannot be successful if it is seen as a quasi-accession exercise.

This report argues that Turkey needs to formulate its own firm but constructive response to the EU's proposal. Turkish diplomacy can cut the Gordian knot of visa-free travel in five strokes.

First: Turkey needs to remind the EU that the visa dialogue is not part of the accession process. Instead, it is a negotiation between equals. Both sides want something: the EU wants a readmission agreement and help in addressing illegal migration from Turkey; Turkey wants visa-free travel. Turkey should state publicly at the outset that it will not accept everything in the roadmap. It is not prepared to introduce airport transit visas, to align its visa policy with that of the EU before full accession, to lift the geographical limitation as part of a visa dialogue, nor to ratify protocols to the European Convention on Human Rights that have not been ratified by all EU member states.

Second: Turkey should declare that it will sign, ratify and then even implement the readmission agreement in line with its legal obligations. However, under the terms of the negotiated readmission agreement it will be obliged to take back third-country nationals only three years after the entry into force of the agreement.

Third: Turkey could demand to see steady progress in the mobility of bona fide Turkish visitors to the EU, including a decline in the rejection rate for visa applications from Turks, and an increase in the share of long-term multiple-entry visas issued.

Fourth: There are two vital areas where Turkey can help build trust inside the EU. One is reducing irregular migration to the EU via Turkey's land and maritime borders. The other is readmission of irregular third-country migrants. Since Turkey is under no legal obligation to do so for three years even after ratifying the readmission agreement, it can decide on the numbers to take back from EU member states all by itself.

Fifth: Turkey should set a realistic deadline. By the end of 2015, at the latest, Turkish travellers should enjoy visa-free travel. If in this period there is no vote, or if the vote is negative, Turkey will notify the EU that the readmission agreement will cease to be in force. This is a legitimate option under the negotiated text of the agreement.

There has never before been an EU candidate country that had been negotiating accession for years and whose citizens were unable to travel without a visa. As Turkey and the EU move towards the fiftieth anniversary of their strategic relationship, which started with the 1963 Association Agreement, the time to overcome this particular legacy of the 1980 coup is now. It is time to cut this Gordian visa knot.

Cutting a Gordian knot: Solving an intractable problem through thinking outside the box. Based on legendary event in the ancient city of Gordiyon, 70 kilometers south-west of Ankara.

For the past year, the Turkish government and the European Commission have failed to advance so much as an inch on one of the most important issues in the EU-Turkey relationship: launching a dialogue on visa liberalisation. European Commissioners have met Turkish ministers, letters have been sent, and phone calls made, all of it to no avail.

As leaders in Ankara understand it, the EU's offer to them is as follows:

"Please fulfil our 70 conditions. Spend more on border control. Help us close your borders to irregular migration to the EU. Ratify and implement a readmission agreement to take back tens of thousands of irregular migrants who reached the EU by transiting Turkey. Offer everybody the possibility to apply for asylum in Turkey and treat the asylum seekers well so they do not go to the EU. Once you do all this, the EU might vote on whether or not to lift the visa requirement for Turkish citizens. Unfortunately we cannot tell you now when such a vote will happen. Nor do we know whether such a proposal would get enough votes to pass in the Council. In the meantime, please trust in our good intentions."

In the eighth year of accession talks, however, trust in the EU is a scarce resource in Ankara.

This paper argues that in order to break out of the current stalemate Turkey needs to formulate its own firm but constructive response to the EU's proposal. Such a response should be developed along the following lines:

"We will fulfil all conditions needed to establish a ‘secure environment for visa-free travel,' as you insist. We will continue to help prevent irregular migrants from crossing from Turkey into Greece. We will ratify and implement the readmission agreement. However, we will only take back – as a gesture of good will, since it is not a legal requirement – a certain number of third-country nationals between 2013 and 2015. The visa liberalisation dialogue cannot be open-ended. If we have not obtained visa-free travel by 2015 we will nullify the readmission agreement. In the next two years we are prepared to show the EU our goodwill; however, we expect the EU to show goodwill as well."

This paper analyses the financial and political costs of such a proposal for Turkey. It carries very little risk and the promise of a big reward. If it were to lead to visa-free travel for Turkish citizens, it would bring about the most important breakthrough in Turkey-EU relations in more than a decade.

In September 1980, Turkey's generals sent tanks onto the streets of Ankara and Istanbul. The coup leaders arrested hundreds of thousands of people, abolished political parties, and imposed a constitution that remains in force. They also left behind another unfortunate legacy: fearing a massive exodus from Turkey, a number of European nations imposed visa requirements for Turkish citizens. Before the coup, Turkish citizens had not needed a visa to travel to Germany, France or the Netherlands. Now they did.

More than three decades have passed since the coup. The European continent has witnessed a revolution in border management and freedom of travel. The result has been dramatic. In 1985, European leaders signed the Schengen Agreement, paving the way towards the abolition of thousands of kilometres of land borders.[1] In 1989, the Berlin Wall came down. In 1991, the EU lifted the visa requirement for Polish citizens travelling to Schengen countries.[2] In 2001 and 2002, it abolished it for Bulgarians and Romanians. In 2009, it was time for Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia. In 2010, visa-free travel arrived for citizens of Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The EU understood that for countries like Poland or Bulgaria to believe in a common European future, their citizens had to be able to travel freely. In 2009, the European Parliament marked the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Iron Curtain with a debate among 20-year olds from across the EU. "What does Europe mean to you?", the participants were asked. "Freedom to travel" was the most popular response.[3]

|

Country |

Visa-free travel |

GDP per capita 2011[4] EU average is 100 |

|

Albania |

2010 |

30 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

2010 |

30 |

|

Macedonia |

2009 |

35 |

|

Serbia |

2009 |

35 |

|

Montenegro |

2009 |

42 |

|

Bulgaria |

2001 |

46 |

|

Romania |

2002 |

49 |

|

Turkey |

? |

52 |

While this border revolution has unfolded across Europe, Turkey has remained on the sidelines. Visa liberalisation has been a crucial element in the EU's relations with Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Albania. Yet until recently it had not even appeared on the agenda of talks between Brussels and Ankara. As late as February 2011, the Council of the EU adopted conclusions concerning Turkey that left out any reference to visa liberalisation.[5]

Things have begun to change only recently. In its conclusions from 21 June 2012, the Council invited the Commission to establish a dialogue with Turkey aimed at visa liberalisation. It was the first time that the EU had mentioned visa-free travel for Turks as a serious possibility.

Almost a year has passed since these Council conclusions. The dialogue on visa liberalisation has yet to begin. What went wrong? And even more importantly, what can be done to put things right?

From the European Commission's point of view, what needs to happen next is obvious. Turkey must accept what the EU Council specified as the single most important condition for a visa liberalisation dialogue: signing a readmission agreement with the EU. Then the Commission would hand over to Turkey a list of official requirements for visa-free travel, otherwise known as the "roadmap". The Council has formally given the Commission a mandate to discuss the lifting of the visa requirement.[6] The roadmap specifies:

"Once all the requirements set out in this Roadmap have fully been met, the Commission will present a proposal to the European Parliament and the Council to lift the visa obligation for Turkish citizens."[7]

As for these requirements, they are similar to those met by Western Balkan countries before their visa obligations were lifted.

A readmission agreement is a bilateral treaty. It commits both sides to take back two classes of illegal migrants: their own citizens; and third country nationals found to have transited the one country en route to the other. The EU has concluded such agreements with all Balkan countries, as well as with Moldova, Georgia, Ukraine and Russia. Every country so far has had to sign, ratify and implement a readmission agreement with the EU before a visa liberalisation dialogue could begin.

In January 2011, the EU and Turkey concluded negotiations on such an agreement. In June 2012, Turkey signalled its consent by initialling the negotiated text.[8] It asked to see the roadmap before signing it. The roadmap was ready in December 2012. For the EU it has been both obvious and reasonable that Turkey should take the next step and sign the agreement at the ministerial level. However, no further step has been taken. The readmission agreement is still not signed. The roadmap has not been handed over. The visa dialogue has not begun.

The EU believes that Turkey has no reason to refuse the offer on hand. Politicians and officials in Ankara see things differently. They suspect traps. They see their concerns ignored. EU member states are viewed as prejudiced. The European Commission is regarded as too weak to ensure fair treatment.

Policymakers in Ankara follow the internal debates in the EU. They notice how the Dutch and the Germans refuse to let Romania and Bulgaria into Schengen even when the Commission asserts that both have fulfilled the necessary technical conditions. They hear how some EU interior ministers call for re-imposing the visa requirement on the Western Balkan countries.[9]

Policymakers in Ankara also follow the debates in the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg. There, at a hearing on 6 November 2012 in a case concerning visa-free travel, EU member state representatives cited a litany of problems that would ensue if the court were to challenge the visa requirement for Turkish citizens.[10] A German official foresaw huge complications. A Dutch one defended the visa requirement as essential. The UK representative cited the overriding threat of illegal migration. His Greek colleague argued implausibly that the EU's visa requirement actually facilitated travel to the EU.

Turkish officials also have concrete misgivings about the offer on the table. These concern implementation of the readmission agreement and its costs, as well as a few specific requirements in the roadmap.

The EU argues that all Turkey needs to do now is sign the readmission agreement. It stresses that this requirement is less demanding than that put to the Western Balkan countries, which had to implement their readmission agreements in order to be offered a visa roadmap.

Turkish officials believe that the EU's position is disingenuous. In the case of the Balkans, the central point of the readmission agreement was to make it easy for the EU to send back Balkan citizens. The fear was that with visa-free travel Bosnians, Albanians and Serbs would enter the EU and stay on, becoming irregular migrants.[11]

However, hardly any third-country nationals have been returned to the Balkans since these agreements entered into force.[12] In a study the Commission made of readmission agreements, it identified 9 applications for the readmission of third-country nationals to Macedonia in two years; 20 applications for the return of third-country nationals to Serbia; and none at all to Bosnia and Herzegovina.[13] These are negligible figures. At the same time, Macedonia readmitted 1,950 of its own citizens in 2012.[14]

Turkey already takes back its own citizens from the EU. For this no new agreement is needed and so far no problems have been reported by any EU member state.[15] The real issue with Turkey is third-country nationals. The Turkish-Greek border has long been a main gateway for irregular migrants to the EU. Between 38,000 and 58,000 people per year were found to have illegally crossed this border in recent years.[16] Turkey fears that by legally committing itself to taking back third country nationals, it would assume a huge burden, becoming a dumping ground for – and the first line of defence against – tens of thousands of irregular migrants from Africa and Asia.

Signing the readmission agreement is not the issue, however; it is the cost of implementation that Turkey fears. The visa roadmap explains that Turkey must "fully and effectively implement the EU-Turkey readmission agreement in all its provisions, in such a manner as to provide a solid track record." Turkish officials, however, have repeatedly stated that they would only implement a readmission agreement and take back third-country nationals in parallel with visa-free travel. On 22 June 2012, Egemen Bagis, Minister for EU affairs and chief negotiator, told his EU counterparts that "the implementation of the Readmission Agreement and visa exemption should be simultaneous."[17]

Turkish negotiators are also convinced that it was their earlier refusal to sign the readmission agreement that compelled the EU to eventually offer Turkey a roadmap. By ratifying and implementing the readmission agreement without obtaining visa liberalisation simultaneously, they reason, Turkey loses its mains source of leverage with the EU.

In June 2012, Turkey's Chief Negotiator with the EU Egemen Bagis told his EU counterparts that Turkey needed to "see and study" the visa liberalisation roadmap before signing the readmission agreement.[18] The Commission finished drafting the roadmap in December 2012. Turkish officials have since studied it. They do not like what they see.

The roadmap sets out some 70 specific conditions, including reforms in the areas of document security, border management, asylum, human rights and cooperation with EU member states and EU agencies.[19] They are similar to the conditions that Serbia or Albania had to fulfil. Turkish officials see no problem with most of these.

However, there are some requirements that Turkey finds unacceptable: first, the demand that it completely overhaul its asylum system; second, the insistence that it change its visa policy towards non-EU countries; and third, the request that it ratify additional protocols to the European Convention on Human Rights, even when some EU members have not yet ratified them themselves.

Turkey's asylum system

Turkey has a very peculiar asylum system. In a nutshell: only citizens of the 47 members of the Council of Europe can apply for asylum in Turkey. These countries do not produce many asylum seekers. In 15 years – between 1995 and 2010 – Turkey officially dealt with just 289 such asylum claims.[20] Asylum seekers in Turkey come from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Somalia, but rarely from Europe.

The origins of Turkey's peculiar system go back to a provision included in the UN Refugee Convention, which was negotiated in the immediate post-World War II period when Europe faced an overwhelming refugee problem. Many states wanted to limit the applicability of the Convention to the refugees in Europe and not to all future victims of persecution and war. So it was initially agreed that only people who had become refugees "as a result of events occurring before 1 January 1951" would be entitled to international protection. Furthermore, it was decided that each country would declare whether it interpreted the reference as "events occurring in Europe before 1 January 1951" or "events occurring in Europe or elsewhere before 1 January 1951."[21]

Turkey chose the first option. Today, it is one of only four states in the world that maintain this geographical limitation. The others are Congo, Madagascar and Monaco. What this means in practice is that when Iranians or Afghans arrive in Turkey they cannot ask the Turkish authorities to grant them asylum. The Turkish authorities allow them to stay, and they can turn to the local UNHCR office. After assessing their claim, the UNHCR – if it finds that they are genuine refugees – will try to resettle them, mostly to the United States, Canada or Scandinavian countries.[22]

The UNHCR procedure takes a long time in Turkey. The numbers of asylum seekers have been rising. According to a UNHCR lawyer, in 2011 it took up to two years just to register a claim; another one to two years until the applicant's interview; and another five to six years before a recognised refugee was resettled.[23] Between 1995 and 2010, UNHCR Turkey received 77,000 asylum claims, of which 40,000 were assessed positively and 10,000 rejected. The remainder were still pending in early 2011.[24] In 2011, 16,324 asylum claims by non-Europeans were submitted to the UNHCR in Turkey, double the 2010 figure. The number is expected to increase further as NATO troops leave Afghanistan in 2014 and as Iran puts pressure on Afghans who have lived there as refugees for years.

In order to join the EU Turkey needs to change this system. It must offer shelter to any person fleeing persecution, regardless of his or her place of origin. This has been obvious since 1998 when the European Commission published its first report on Turkey. It wrote that "the lifting of this reservation is essential for Turkey's alignment on the rules in force in the European Union."[25]

However, for now Turkey is not about to join the EU. The negotiation chapter under which asylum policy falls, chapter 24, has not even been opened. Turkey has always maintained that it will lift the geographical limitation just before acceding to the EU.

Turkish officials were therefore taken aback that the roadmap demanded an asylum system "in compliance with the EU acquis … thus excluding any geographical limitation." As Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu wrote in a letter to the European Commissioner for Home Affairs Cecilia Malmstrom:

"It is impossible for Turkey to lift the ‘geographical limitation' … In fact, ‘geographical limitation' will have no impact on the implementation of the Turkey-EU Readmission Agreement. Besides, ‘geographical limitation' did not have any obstructing effect for the efforts and sacrifices made by Turkey in extending safety and shelter for persons from its region in cooperation with international institutions."[26]

This does not mean that Turkey is opposed to reforming its asylum system, however. In April 2013 the Turkish parliament adopted a new "Law on Foreigners and International Protection." Previously, individuals in search of international protection were not allowed to work and received hardly any assistance. They were settled in one of 51 designated towns and had to pay a residence fee of some 132 Euro per person every six months. Sometimes, but only sometimes, they received humanitarian help.

A growing number of people in Turkey had found the system unworthy of the world's 16th largest economy. Under the new law, individuals in search of protection will be entitled to request accommodation and assistance. They will have schooling, health protection and access to the labour market. Turkey will also set up a new asylum authority and introduce the possibility of appeal.

Implementation of the new law will require a major effort. New reception centres will need to be built and many institutions, including the new asylum authority, will have to learn to deal with different aspects of a modern asylum system. Some human rights experts expect that full implementation of the new law will take several years. They also worry about the implications of lifting the geographical limitation too early. "This would be a black hole for asylum seekers," one of them told ESI.

Commissioner Malmstrom and Enlargement Commissioner Stefan Fule praised the adoption of the new law and declared that "once properly implemented, this law will also address several issues identified in the Commission Roadmap for visa liberalisation, which will constitute the basis for the visa liberalisation dialogue once this will start."[27] A UNHCR spokesperson stated that it was "an important advancement for international protection, and for Turkey itself, which has a long history of offering protection for people in need."[28] This was a reference to the hundreds of thousands Syrian refugees that Turkey has sheltered, so far with little help from the outside world.[29]

Given its rising standing in the world and its domestic debate on asylum policy, it appears that the question for Turkey is not if but when it will lift the geographical limitation. Full implementation of the new law on foreigners and asylum will also prepare the ground for this. In addition, Turkey is ready to help the EU reduce irregular transit migration. At this moment, Turkey is shielding Europe from a wave of hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees, offering them shelter and food. For Turkey, this is proof that it is able to help both the EU and people in need of protection without lifting the geographical limitation.

Turkey's visa policy

On visa policy, the roadmap demands that Turkey

"pursue the alignment of the EU Turkish visa policy, legislation and administrative capacities towards the EU acquis, notably vis-à-vis the main countries representing important sources of illegal migration for the EU."[30]

The roadmap also states that Turkey has to introduce an "airport transit visa." This type of visa is currently not required, which makes transiting through Istanbul easy and increases revenues for Turkish airports and for the country's national carrier, Turkish Airlines.

Turkey's generous visa policy has been a central element of its foreign policy in recent years. From 2002 until 2005, Turkey progressively harmonised its visa policy with the EU's by imposing visa requirements on the same countries whose nationals also needed a visa to enter the EU. As one scholar noted,

"… by 2005, Turkey was only five countries short on the list to be fully aligned to the Schengen negative list (down from 13 countries in 2002)."[31]

A few years later Turkey began to reverse its policy of harmonisation. It now sought to systematically remove visa requirements with as many countries as possible. In 2009, Turkey lifted its visa requirements with Syria, Libya and Jordan, all of which were on the EU's "black list" of countries whose citizens needed a visa to enter. In 2010, it did the same with Russia and Lebanon. In May 2011, Minister of Foreign Affairs Ahmet Davutoglu declared that in the previous eight years Turkey had reached visa-free agreements "with no less than 50 countries."[32]

This policy of openness has had dramatic results. Turkey has experienced record tourist numbers year in, year out, rising from 21 million in 2005 to 32 million in 2011.[33] It is a tourist destination for Europeans, Russians and visitors from Muslim countries. In 2012 the largest number came from Germany (5 million), followed by Russia (3.6), the United Kingdom (2.5), Bulgaria (1.5) and Georgia (1.4). Iran, with more than 1 million visitors, was also among the top ten countries of origin.

Tourism revenues are vital for the Turkish economy. They are also fuelling the rapid expansion of Turkish Airlines. A licence has recently been issued for the construction of a new Istanbul airport, planned to become the world's biggest.[34] In the first quarter of 2013, Istanbul has seen the highest number of visitors ever.[35] After London, Paris, Bangkok and Singapore, it is the fifth most visited city in the world. It is also among the top ten venues for international congresses.[36]

|

Rank |

City |

Nr of int. congresses |

|

1. |

Vienna |

181 |

|

2. |

Paris |

174 |

|

3. |

Barcelona |

150 |

|

4. |

Berlin |

147 |

|

5. |

Singapore |

142 |

|

6. |

Madrid |

130 |

|

7. |

London |

115 |

|

8. |

Amsterdam |

114 |

|

9. |

Istanbul |

113 |

|

10. |

Beijing |

111 |

Turkey has consistently repeated that it is not prepared to overhaul its visa regime before it actually joins the EU. Previous EU applicants did not have to do so. Poland maintained visa-free travel for Ukrainians till the eve of accession, as has Croatia for Turks until April 2013.

As Davutoglu wrote in a letter to Commissioner Malmstrom:

"Turkey's alignment with the Schengen visa regime including alignment with the transit visa regime will be realized upon accession, as it was the case with other aspirant countries." [37]

The Commission has tried to address Turkey's concerns. In her reply to Ahmet Davutoglu, Malmstrom wrote:

"… the Commission looks for credible means to combat irregular immigration, leaving to Turkey the choice of the most effective one. It is not our intention to request Turkey to align its Visa policy to the one of the Union before accession." [emphasis added][38]

The roadmap asks Turkey to target the "main countries representing important sources of illegal migration for the EU". In other words, unless a given country's visa-free regime with Turkey contributes to a significant influx of illegal migrants to Europe, the EU should not be concerned.

The European Commission has also told Turkish officials that a provision in the new Law on Foreigners and International Protection already fulfils the requirement concerning the airport transit visa.[39] The concern of Turkish officials is whether EU member states will agree with this assessment.

Additional protocols to the ECHR

The roadmap requires Turkey to ratify various international agreements, including the additional Protocols 4 and 7 to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Turkey states that it is not prepared to do this.

Protocol 4 dates from 1963. In addition to banning imprisonment for debt and prohibiting expulsion of citizens and collective expulsions of third-country nationals, it also establishes the right of freedom of movement and choice of residence within a state (Art. 2).[40] The problem as seen in Ankara relates to the Cyprus issue. In 1990, a Cypriot of Greek background complained before the European Court of Human Rights that he possessed property in the northern part of Cyprus and was unable to enjoy use of it. He based his complaint on several articles of the Convention and its protocols, including Protocol 4. However, the court noted that since Turkey had not ratified the protocol, the complaints "must be considered … inadmissible."[41] Turkey fears similar court cases if it ratified Protocol 4. Reflecting the mood of suspicion in Ankara, some see this as a possible trap laid by Cyprus.

In fact, EU members Greece and the UK have not ratified Protocol 4 either. Nor has Switzerland, which was nonetheless able to join Schengen.[42] Protocol 7, which deals mainly with various procedural safeguards in criminal cases,[43] has not been ratified by Germany, the Netherlands and the UK.[44] As Foreign Minister Davutoglu wrote in his letter to Commissioner Malmstrom:

"Visa liberalization for Turkish citizens should not be conditioned to Turkey's adoption of international agreements that even a number of EU Member States are not yet a Party to."[45]

A matter of trust?

For all these reasons, Turkish officials have suggested that the Commission revise the roadmap. In response the Commission has argued that any substantial changes are both impossible and unnecessary.

To try to amend the roadmap would imply reopening complex talks with sceptical member states. The Commission already spent half a year – from July to December 2012 – consulting EU governments on the content of the roadmap. In December 2012, they finally endorsed it. It is certain that any attempt to make changes now would delay the launch of a visa dialogue for a long time. At the same time the Commission is convinced that changing the roadmap is unnecessary. As Malmstrom put it in her letter to Davutoglu:

"… this text contains the technical requirements the Commission, on the basis of its knowledge and of its experience, believes should be fulfilled. This is a Commission document, endorsed by the Council, representing our position for conducting the Dialogue and obviously I am not requesting Turkey to endorse or to approve it." [46]

This has not reassured Turkey's officials. As one senior Turkish official in Ankara explained to ESI:

"This roadmap may well be a Commission document that we do not need to approve, but we are asked to implement it!"

How can this gap in expectations be bridged in a way that satisfies both sides?

The EU has not resisted the temptation to model the visa liberalisation process after EU accession talks. Handing over the roadmap is similar to the explanatory screening, when the European Commission explains to an accession country what it is supposed to do under each negotiation chapter. The reports on roadmap implementation progress are like progress reports assessing the level of compliance with the EU acquis. In the accession talks, it is the EU members who decide under which conditions to accept new members. It is a "take it or leave it" process: there is no room for serious negotiation.

However, the Turkey-EU visa liberalisation dialogue is different. Both sides want something: the EU wants a readmission agreement and help in addressing illegal migration from Turkey; Turkey wants visa-free travel. Both must be ready to give something in return. To succeed both sides must retain leverage until the very end. The EU-Turkey visa dialogue cannot be successful if it is seen as a quasi-accession exercise. For success, both sides need to take into account the political constraints of the other party. Both also need a negotiating position that allows for compromise. The EU roadmap, drawn up without any consultation with Turkey, cannot be regarded as holy writ. It is just one side's opening negotiating position.

ESI suggests that the visa liberalisation process with Turkey be launched on a different approach. Turkish diplomacy can cut the Gordian knot of visa-free travel in five strokes.

Turkey needs to remind the EU that the visa dialogue is not part of the accession process. Insetad, it is a negotiation between equals.

Turkey should state clearly and publicly at the outset that it will not accept everything in the roadmap. It should draw up its own Action Plan and explain precisely what it is – and is not – prepared to do. It should stress that it takes no issue with most of the EU's priorities as expressed in the roadmap. It should also state from the outset that it is not prepared to introduce airport transit visas, to align its visa policy before full accession, to lift the geographical limitation as part of a visa dialogue, nor to ratify protocols to the European Convention on Human Rights that have not been ratified by all EU member states. All these things can happen once Turkey is on the verge of joining the EU. They do not have to happen before.

Turkey should declare that it will sign, ratify and then even implement the readmission agreement in line with its legal obligations.

However, Turkey should also remind the EU, and explain to its own public, that under the terms of the negotiated readmission agreement it will be obliged to take back third-country nationals only three years after the entry into force of the agreement:

"The obligations set out in Articles 4 [readmission of third-country nationals and stateless persons to Turkey] … of this Agreement shall only become applicable three years after the date referred to in Paragraph 2 of this Article [which is the date of the entry into force of the agreement]."[47]

There in only one exception:

"During that three-year period, [the obligations concerning readmission of third-country nationals] shall only be applicable to stateless persons and nationals from third-countries with which Turkey has concluded bilateral treaties or arrangements on readmission."[48]

This is not onerous. Turkey has readmission agreements with eleven countries,[49] only two of which – Pakistan and Syria – produce significant numbers of irregular migrants that move on to the EU.[50] The readmission agreement with Syria is currently not operational due to the fighting in Syria. This leaves Pakistanis as the only nationals that Turkey might have to take back immediately.

In short: ratifying and implementing the readmission agreement would be an important signal, but it would not impose any significant costs on Turkey for at least three years. Before then, either the visa requirement will have been lifted or Turkey will have withdrawn from the agreement (see below point five).

If the visa dialogue is a negotiation, it will require concrete steps that benefit both sides from the very outset. The EU, too, must take on commitments whose implementation Turkey can monitor to gauge the EU's seriousness. A regular review of progress every six months would help assess how far both sides have come in meeting their mutual commitments.

In this context Turkey could demand to see steady progress in the mobility of bona fide Turkish visitors to the EU. The EU has already promised this, referring to the option to "fully exploit all possibilities provided by the EU Visa Code."[51] This is too vague and unspecific, however. Whether it is living up to this promise should be assessed by way of specific benchmarks: a decline in the rejection rate for visa applications from Turks, and an increase in the share of long-term (more than a year) multiple-entry visas issued. All EU member states could further streamline the visa application procedure, e.g. by exempting bona-fide travellers from having to submit their application in person. (Once they have submitted their fingerprints and digital signature, they are valid for 5 years). The number of categories of people for whom EU member states waive or reduce the Schengen visa fee of 60 Euro should also be broadened. On top of that, the Commission could propose to amend the EU Visa Code to lift the visa fee for countries negotiating accession to the EU.

Another area where Turkey should expect measurable results from the EU and its member states during the visa dialogue is increased financial support to deal with the Syrian refugee crisis and the fight against irregular migration. A joint declaration attached to the readmission agreement already promises "reinforced financial assistance" for "institution and capacity building to enhance Turkey's capacity to prevent irregular migrants from entering, staying and exiting its territory." It also mentions EU financial assistance for integrated border management and migration.[52]

If there is a lot that that the EU can and should do to build trust on the Turkish side, there are also two vital areas where Turkey can help build trust inside the EU. One is reducing irregular migration to the EU via Turkey's land and maritime borders. The other is readmission of irregular third-country migrants who reach the EU through Turkey.

The roadmap suggests a host of measures aimed at achieving "a significant and sustained reduction of the number of persons managing to illegally cross the Turkish borders either for entering or for exiting Turkey." These range from deploying more and better-trained border guards and modern equipment at the borders to improving border controls and working closely with Frontex, the EU's border agency.

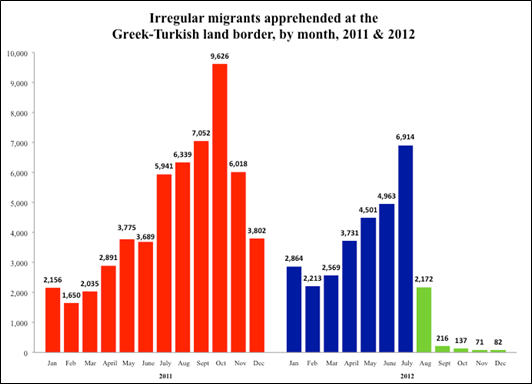

Turkey has already begun to make serious efforts in 2012. Together with measures taken by Greece and Frontex, these have contributed to a dramatic drop in the number of irregular migrants who reach Greece by crossing the river Evros (in Turkish: Meric) along the border with Turkey. In August 2012, Greece deployed an additional 1,881 border guards at the land border with Turkey, equipped with boats and night-vision gear purchased with EU funds. A new 4-meter high 10.5-kilometre long fence has been raised along a popular crossing area. Cooperation with Turkish border authorities has improved. Greek police have also stopped the policy of detaining undocumented migrants for only a few hours before letting them go.[53]

|

Border |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Greek-Turkish land border |

14,480 |

8,782 |

47,706 |

54,974 |

30,433 |

|

Greek sea borders (mostly with Turkey) |

31,729 |

28,841 |

6,175 |

2,598 |

6,444 |

|

Total Greek-Turkish borders |

46,209 |

37,623 |

53,881 |

57,572 |

36,877 |

|

All detections at EU external borders |

159,092 |

104,599 |

104,049 |

140,980 |

72,437 |

The effect has been immediate. Only 500 irregular migrants were detected crossing the land border between September and December 2012, as compared to 26,500 over the same period in 2011.[55] And while the number of migrants who use the sea route has increased somewhat (2,202 detected between January and March 2013, compared with 550 in the same period the year before[56]) the total number still makes for a dramatic drop.

Continuing these efforts also has profound implications for the second area where Turkey can help the EU: readmission of third-country nationals. If fewer migrants cross Turkey en route to the EU, there are also fewer that Turkey would have to take back. If Turkey continues to cooperate with both Frontex and Greece, the numbers are bound to remain significantly lower than between 2008 and 2011.

Concerning readmission, Turkey should offer to immediately increase the number of third-country nationals that it is willing to take back from EU member states. Since it is under no legal obligation to do so for three years even after ratifying the readmission agreement, it can decide on the numbers all by itself.

There are good reasons to believe that requests for readmission of third-country nationals would turn out to be far less frequent than the debate in Turkey suggests. In February 2011 the European Commission presented an evaluation of all twelve readmission agreements then in force with the EU. It concluded that, leaving out Ukraine, a total of only 91 applications were filed under all the readmission agreements.[57] The reason is that some member states, as a matter of policy, only send migrants back to their countries of origin, and never to their countries of transit.[58] The study concluded that "the third-country national clause is actually rarely used by member states, even with transit countries like the Western Balkans."[59]

As for Ukraine, the experience is also telling. Like Turkey, Ukraine has been a major transit country for irregular migrants.[60] It concluded a readmission agreement with the EU, which entered into force on 1 January 2008 and which stipulated a two-year transitional period concerning the return of third-country nationals. Many Ukrainians were alarmed, convinced that the readmission agreement would "turn Ukraine into a storehouse for illegal migrants,"[61] as one tabloid wrote. Just before the transitional period expired, a nationalist party leader called the agreement "a crime against the nation." "Experts estimate that just the first wave of migrants that will be sent to Ukraine immediately after 1 January will reach 150,000 people," he warned.[62]

Reality proved to be very different. Instead of 150,000, only 398 third-country nationals (and 71 Ukrainian citizens) were returned to Ukraine in 2010. In 2011, it was even less: 243 third-country nationals. In 2012, the number of returned third-country nationals dropped to 108.[63]

The only important number of requests for readmission of third-country nationals to Turkey would likely come from Greece. Turkey has had a bilateral readmission agreement with Greece for more than a decade already. Between 2002 and 2011, Greece submitted 101,500 requests, almost exclusively third-country nationals. Turkey accepted 11,500 requests. 3,700 migrants were actually returned to Turkey.[64] However, in the first six years of the readmission agreement between Greece and Turkey, the average annual number of requests for readmission from Greece was below 5,000. With current effort on the border showing an effect already, this is a realistic figure to base assessments on.

Imagine the political signal if Turkey offered to effectively take back from Greece up to 5,000 third-country nationals a year as a measure of good will. This would be a very impressive improvement of the current situation (see table 6).

What would the costs to Turkey be if it made such an offer? The negotiated agreement specifies that the country requesting the readmission of an irregular migrant has to bear "all transport costs incurred" until "the border crossing point of the Requested State."[65] The costs in Turkey after readmission are also manageable. In recent years, Turkey itself has apprehended more than 40,000 irregular migrants per year. It has deported around 25,000 people per year. It should be able to cope with an additional 5,000 migrants returned from Greece. Since there is no legal obligation under the readmission agreement to take back third-country nationals for three years, it remains up to Turkey to increase or decrease this figure.

|

Year |

Number of persons whose readmission Greece requested |

Number of persons whose readmission Turkey accepted |

Number of persons actually readmitted |

|

2002 |

8,470 |

926 |

745 |

|

2003 |

5,380 |

1,002 |

374 |

|

2004 |

4,026 |

256 |

119 |

|

2005 |

2,087 |

330 |

152 |

|

2006 |

2,251 |

456 |

127 |

|

2007 |

7,728 |

1,452 |

423 |

|

2008 |

26,516 |

3,020 |

230 |

|

2009 |

16,123 |

974 |

283 |

|

2010 |

10,198 |

1,457 |

501 |

|

2011 |

18,758 |

1,552 |

730 |

|

TOTAL |

101,537 |

11,425 |

3,684 |

The number of up to 5,000 readmissions can also be put in another context. Turkey is currently hosting 320,000 registered refugees from Syria. The estimate of unregistered Syrian refugees is even higher.[67] To allow back some 5,000 third-country nationals a year for a limited period would be a negligible cost by comparison. It would however dramatically increase the chance for visa liberalisation.

|

Year |

Number of persons apprehended |

Number of persons deported |

|

2007 |

64,290 |

54,692 |

|

2008 |

65,737 |

50,758 |

|

2009 |

34,345 |

24,150 |

|

2010 |

32,667 |

23,583 |

|

2011 |

44,415 |

26,889 |

|

2012 |

42,690 |

n.a. |

Turkey does not need to accept an open-ended process, but should set a realistic deadline. The readmission agreement would require accepting requests for the readmission of third-country nationals three years from the agreement's entry into force; this means a deadline should be set before then. It took Serbia and the EU less than two years to move from the beginning of the roadmap process to full visa liberalisation. This also provides a good benchmark.

Turkey could state that it expects the Commission to issue a positive assessment before summer 2015. Once this happens it expects the European Parliament and the Council to vote on lifting the visa requirement for Turkish citizens within no more than six months. By the end of 2015, at the latest, Turkish travellers should enjoy visa-free travel.

If in this period there is no vote, or if the vote is negative, Turkey will notify the EU that the readmission agreement will cease to be in force. This is a perfectly legitimate option under the negotiated text of the agreement:

"Each Contracting Party may denounce this Agreement by officially notifying the other Contracting Party. This Agreement shall cease to apply six months after the date of such notification."[69]

For Turkey such a deadline would also provide a powerful political argument to justify proceeding with the signature and ratification of the readmission agreement.

Both the Council and the European Parliament will have to take a vote on the proposal on visa liberalisation In the European Parliament the proposal will need only a simple majority to pass. The bigger hurdle will be the member states voting in the Council.

In the Council, the proposal will require a qualified majority.[70] No single EU member state will be able to block it. A winning strategy to guide Turkey's outreach efforts could be the following:

Turkey first secures the support of five already Turkey-friendly EU member states that have many votes or are particularly influential: Italy, Poland, Romania, Spain and Sweden. They should come out and state that – if there is a good record of reform and continued strong results from cooperation with Turkey on migration and readmission - they would be prepared to vote for lifting the visa by 2015;

Turkey secures the support of a large number of smaller member states that have already declared their support or are likely to be supportive: Bulgaria, Croatia (to join on 1 July 2013), Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia and Slovenia;

Turkey secures the support of Germany.

Under the current voting system including Croatia, this would be enough votes. The votes of Austria, Cyprus, Luxembourg, France and the Netherlands are not needed.[71]

In the coming two years, Turkey would need to engage in active diplomacy and outreach to persuade a critical number of EU member states to vote for visa liberalisation. In the run-up to the 50th anniversary of the Turkey-EU Association Agreement in September 2013, Turkey, the European Commission and interested member states might also work on drawing up a concrete Action Plan on People-to-People Contacts in preparation of the 50th anniversary of the Turkey-EU Association Agreement in September 2013.

The key idea behind ESI's proposal how to cut the visa knot is that the costs, risks and benefits must be shared equally for a successful EU-Turkey visa liberalisation process. Even if Turkey does not lift the geographical limitation, does not align its visa policy, does not introduce airport transit visa and does not ratify Protocols 4 and 7 of the European Convention on Human Rights, the EU would benefit from the readmission agreement and the fulfilment of most roadmap conditions. It would still be a win-win situation.

If the risks and costs are low, the rewards are potentially very big, for both Turkey and the EU. As one senior Turkish official told ESI recently in Ankara: "People hardly notice the opening of another negotiation chapter. But they do care about visa." So should policy makers in both Brussels and Ankara.

There has never before been an EU candidate country that had been negotiating accession for years and whose citizens were unable to travel without a visa. As Turkey and the EU move towards the fiftieth anniversary of their strategic relationship, which started with the 1963 Association Agreement, the time to overcome this particular legacy of the 1980 coup is now. It is time to cut this Gordian visa knot.

Annex A: Council Voting Scenarios

|

Current voting system (it can also be requested between Nov. 2014 and March 2017) 234 votes needed |

Double majority system (from 1 November 2014[72]) 55 per cent of member states, at least 15 states representing 65 per cent of the EU population |

|

|

Friends of Turkey: |

Inhabitants |

|

|

Italy |

29 votes |

60.8 million |

|

Poland |

27 votes |

38.5 million |

|

Romania |

14 votes |

21.4 million |

|

Spain |

27 votes |

46.2 million |

|

Sweden |

10 votes |

9.5 million |

|

Likely to be supportive: |

||

|

Bulgaria |

10 votes |

7.3 million |

|

Croatia (from 1 July 2013) |

7 votes |

4.4 million |

|

Czech Republic |

12 votes |

10.5 million |

|

Denmark |

7 votes |

5.6 million |

|

Estonia |

4 votes |

1.3 million |

|

Finland |

7 votes |

5.4 million |

|

Greece |

12 votes |

11.3 million |

|

Hungary |

12 votes |

10 million |

|

Latvia |

4 votes |

2 million |

|

Lithuania |

7 votes |

3 million |

|

Malta |

3 votes |

0.4 million |

|

Portugal |

12 votes |

10.5 million |

|

Slovakia |

7 votes |

5.4 million |

|

Slovenia |

4 votes |

2.1 million |

|

Interim total |

215 votes |

256 million |

|

Germany |

29 votes |

81 million |

|

TOTAL |

244 votes (enough) |

20 member states of 26 = 77 per cent (enough) 337.5 million inhabitants = 67 per cent (enough) |

Annex B: Letters Clarifying Positions

EXCERPTS

Letter from Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu

to Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmström

16 January 2013

Dear Commissioner Malmström,

… Turkey is already taking necessary measures towards developing a close cooperation in prevention and control of irregular migration while paying attention to the human rights aspect of migration management.

… I would like to inform you of certain crucial points pertaining to this dialogue which should be taken into account within the Road Map.

As we had previously underlined several times in our discussions with you and other EU officials, the implementation of the Readmission Agreement should be simultaneous with the start of the visa free regime for Turkish citizens …

Turkey's alignment with the Schengen visa regime including alignment with the transit visa regime will be realized upon accession, as it was the case with other aspirant countries. …

It is impossible for Turkey to lift the "geographical limitation" with regard to the asylum procedures of the 1951 Geneva Convention and its 1967 Protocol which is a right recognized by the Convention and confirmed by the European Court of Human Rights. In fact, "geographical limitation" will have no impact on the implementation of the Turkey-EU Readmission Agreement. Besides, "geographical limitation" did not have any obstructing effect for the efforts and sacrifices made by Turkey in extending safety and shelter for persons from its region in cooperation with international institutions …

Visa liberalization for Turkish citizens should not be conditioned to Turkey's adoption of international agreements that even a number of EU Member States are not yet a Party to …

As we will be implementing the required measures of the Readmission Agreement, Turkey believes that u would be necessary to make additional resources available with a view to meet common challenges through a specific financial mechanism complementing the existing financial cooperation framework …

I would like to conclude that Turkey will sign the Readmission Agreement, should the Road Map take into account our above mentioned concerns …

Yours sincerely,

Ahmet Davutoğlu

EXCERPTS

Letter from Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmström

to Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu

28 January 2013

Dear Minister,

… the concerns you express are serious and they deserve careful consideration.

Some of them are already known, like the issue of the possible alignment of Turkey Visa policy to the one of the Union. I have already addressed this concern in my above-mentioned letter, underlining that the Commission looks for credible means to combat irregular immigration, leaving to Turkey the choice of the most effective one. It is not our intention to request Turkey to align its Visa policy to the one of the Union before accession. Moreover, once the visa dialogue is launched, we stand ready to intensify our cooperation to support Turkey to manage its external borders and to combat irregular migration, which is affecting your country as well.

Some other points must be examined more in depth, like the one concerning the "geographic limitation" in respect of the Geneva Convention and Protocols. Also here we have to assess together what are the most effective ways to ensure the results necessary for Visa 1iberalisation …

I want to underline that this text contains the technical requirements the Commission, on the basis of its knowledge and of its experience, believes should be fulfilled. This is a Commission document, endorsed by the Council, representing our position for conducting the Dialogue and obviously I am not requesting Turkey to endorse or to approve it.

The Dialogue we propose offers the appropriate framework to clarify and to address all relevant concerns expressed by both sides, including the possibility to make available additional financial resources to support actions covered by the process. Furthermore, in this context I am confident that negotiations will allow us to find the most appropriate and mutually acceptable solutions for reaching the common objective of visa-free travel for Turkish and EU citizens …

Yours Sincerely,

Cecilia Malmström

Annex C: EU roadmap towards a visa-free regime with Turkey

Excerpts of key requirements

"The present Roadmap includes a list of reforms to be adopted and effectively implemented by Turkey so that the visa obligation may be lifted. These reforms are necessary to ensure the freedom of movement in a secure and predictable manner."

Requirements related to readmission of illegal immigrants:

Ratify the EU-Turkey readmission agreement initialed on 21 June 2012

Fully and effectively implement the EU-Turkey readmission agreement in all its provisions, in such a manner as to provide a solid track record of the fact that readmission procedures function properly in relation to all Member States;

Strengthen the capacity of the competent authority to process readmission applications

Compile and share in a timely manner detailed statistics on readmission;

Effectively seek to conclude and implement readmission agreements with the countries that represent sources of important illegal migration flows directed towards Turkey or the EU Member States.

BLOCK 1: Document Security

Continue issuing machine readable biometric travel documents in compliance with ICAO

Gradually introduce international passports with biometric data, including photo and fingerprints, in line with the EU standards

Establish training programmes and adopt ethical codes on anti-corruption targeting the officials of any public authority that deals with visas, breeder documents or passports;

Promptly and systematically report to Interpol/LASP data base on lost and stolen passports;

BLOCK 2: Migration management

Carry out adequate border checks and border surveillance along all the borders of the country, especially along the borders with EU member states, in such a manner that it will cause a significant and sustained reduction of the number of persons managing to illegally cross the Turkish borders

Adopt and effectively implement legislation governing the movement of persons at the external borders, as well as legislation on the organisation of the border authorities … in line with the principles and best practices enshrined in the EU Schengen Border Code and the EU Schengen Catalogue

Deployment at the border crossing posts and along all the borders of the country, especially on the borders with the EU member states, of well-trained and qualified border guards (in sufficient number), as well as the availability of efficient infrastructure, equipment and IT technology

Establish training programmes and adopt ethical codes on anti-corruption targeting officials involved in the border management;

Implement in an effective manner the Memorandum of Understanding signed with FRONTEX

Ensure that border management is carried out in accordance with the international refugee law

Ensure adequate cooperation with the neighbouring EU Member States

Visa policy

Enhance training on document security at the consular and border staff of Turkey

Abolish issuance of visas at the borders as an ordinary procedure for the national of certain non-EU countries, and especially for countries representing a high migratory and security risk to the EU

Put in use the new Turkish visa stickers with higher security features, and stop using the stamp visas

Introduce airport transit visas

Make the access more difficult for those willing to enter the Turkish territory with the purpose to subsequently attempt to illegally cross the external borders of the EU,

Pursue the alignment of the EU Turkish visa policy, legislation and administrative capacities towards the EU acquis, notably vis-à-vis the main countries representing important sources of illegal migration for the EU

International Protection

Adopt and effectively implement legislation and implementing provisions, in compliance with the EU acquis and with the standards set by the Geneva Convention of 1951 on

refugees and its 1967 Protocol, thus excluding any geographical limitation

Establish a specialised body responsible for the refugee status determination procedures with the possibility for an effective remedy in fact and law before a court or tribunal as well as for ensuring the protection and assistance of asylum seekers and refugees;

Provide adequate resources and funds ensuring a decent reception and protection of the rights and dignity of asylum seekers and refugees;

Persons who are granted a refugee status should be given the possibility to self-sustain, to access to public services, enjoy social rights and be put in the condition to integrate in Turkey.

Illegal Migration

Adopt and implement legislation providing for an effective migration management and including rules aligned with the EU and the Council of Europe standards, on the entry, exit, short and long-term stay of foreigners and the members of their family, as well as on the reception, return and rights of the foreigners having been found entering or residing in Turkey illegally

Ensure effective expulsion of illegally residing third country nationals from its territory

BLOCK 3: Public order and security

Preventing and fighting organised crime, terrorism and corruption

Continue implementation of National Strategy and Action Plan for the fight against organised crime (in particular cross-border aspects)

Sign and ratify the Council of Europe's Convention on Action against Human Trafficking

Provide adequate infrastructures and sufficient human resources and funds ensuring a decent reception and protection of the rights and dignity of victims of trafficking

Ratify the Council of Europe Convention on Laundering, Search, Seizure and Confiscation of the Proceeds from Crime and on the Financing of Terrorism (CETS 198)

Adopt and effectively enact legislation to meet recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) on establishing a system on the freezing of assets and a definition of the financing of terrorism

Ratify the Council of Europe Convention on Cybercrime

Judicial co-operation

Implement and comply with international conventions concerning judicial cooperation in criminal matters (in particular the Council of Europe Convention on extradition (n.24 of 1957, including the not yet implemented additional protocols of 1975, 2010 and 2012), on mutual assistance on criminal matters (n.30 of 1959, including the not yet implemented additional protocol of 2001), and on the transfer of sentenced persons ( n.112 of 1983, including the not yet implemented additional protocol of 1997);

Take measures aimed at improving the efficiency of judicial co-operation in criminal matters of judges and prosecutors with the EU Member States and with countries in the region

Develop working relations with EUROJUST

Continue implementing the 1980 Hague Convention on civil aspects of the international child abduction, and accede to the 1996 Hague Convention on Jurisdiction, applicable law, recognition, enforcement and co-operation in respect of parental responsibility and measures for the protection of children, as well as to the 2007 Hague Convention on the international recovery of child support and others form of maintenance

Provide effective judicial cooperation in criminal matters to all the EU Member States, including in extradition matters

Law enforcement co-operation

Take necessary steps to ensure effective and efficient law enforcement co-operation among relevant national agencies

Reinforce regional law enforcement services co-operation, including by on time sharing of relevant information with competent law enforcement authorities of EU Member States

Effectively cooperate with OLAF and EUROPOL in protecting the Euro against counterfeiting

Strengthen the capacities of the Turkish Financial Crimes Investigation Board (MASAK)

Continue implementing the Strategic Agreement with EUROPOL

Conclude with EUROPOL and fully and effectively implement an Operational Cooperation Agreement

Data protection

Sign, ratify and implement relevant international conventions, in particular the Council of Europe Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data of 1981 and its additional Protocol n.181

Adopt and implement legislation on the protection of personal data in line with the EU standards

BLOCK 4: Fundamental Rights

Issue of identity documents

Provide information about the conditions and circumstances for the acquisition of Turkish citizenship

Ensure full and effective access to travel and identity documents for all citizens including women, children, people with disabilities, persons belonging to minorities, internally displaced people, and other vulnerable groups;

Provide accessible information on registration requirements to foreigners wishing to reside in Turkey, and ensure equal and transparent implementation

Citizens' rights and respect for and protection of minorities

Develop and implement policies addressing effectively the condition of the Roma social exclusion, marginalisation and discrimination in access to education and health services, as well as its difficulty to access to identity cards, housing, employment and participation in public life

Ratify the additional Protocols n.4 and 7 to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

Revise - in line with the ECHR and with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) case law, the EU acquis and EU Member States practices - the legal framework as regards organised crime and terrorism, as well as its interpretation by the courts and by the security forces and the law enforcement agencies, so as to ensure the right to liberty and security, the right to a fair trial and freedom of expression, of assembly and association in practice.

About ESI's Schengen White List Project

ESI White List Project team and Stiftung Mercator meeting President Abdullah Gul

ESI has been working on the issue of visa liberalisation since 2006.

We would like to express our gratitude to our advisory board, in particular Chairman Giuliano Amato and Board Members Otto Schily and Charles Clark for providing guidance in this endeavour. We are also grateful to all donors that have enabled us to do this analysis. Since 2012, we have focused on Turkey, seeking to contribute to the launch of a process between Turkey and the EU. Our main donor for this work has been the Stiftung Mercator.

ERSTE Stiftung and OSI's Think-Tank Fund have helped us deal with wider issues related to visa liberalisation in the Balkans and other countries trying to obtain visa-free travel with the EU. In 2009/2010 we ran a project aimed at ensuring a fair visa liberalisation process for five Western Balkan countries. This was supported by the Robert Bosch Stiftung. Visit our website "Europe's Border Revolution and the Schengen White List Project" at www.esiweb.org/whitelistproject.

Relevant ESI publications:

- ESI interview: Today's Zaman, "Knaus: Turkey, EU to develop more trust through plans for visa-free regime" (27 January 2013)

- ESI report: Saving visa-free travel – Visa, Asylum and the EU roadmap policy (1 January 2013)

- ESI analysis: Moving the goalposts? An analysis of the Kosovo visa roadmap (6 July 2012)

- ESI discussion paper: Nine reasons for a visa liberalisation process with Turkey (20 June 2012)

- ESI backgrounder: Facts and figures related to visa-free travel for Turkey (15 June 2012)

- ESI news: ESI meeting President Gul and EU ambassadors in Ankara to discuss visa free travel for Turks (22 March 2012)

- ESI commentary: "Being fair to Turkey is in the EU's interest" (12 March 2012)

- Rumeli Observer: Land borders in Europe. A dramatic story in three acts (12 October 2011)

- Rumeli Observer: Amexica and other reflections on border wars (12 December 2010)

- ESI Report: A very special relationship. Why Turkey's EU accession process will continue

- (11 November 2010)

- ESI/Populari report: "Bosnian Visa Breakthrough" (16 October 2009)

- ESI Scorecard: Which Balkan countries deserve visa-free travel (22 May 2009)

- Glossary: Understanding Europe's borders (A to Z)

There have also been more than 400 articles in international media referring to the ESI White List Project and our work on visa liberalisation.

[1] ESI Rumeli Observer, Land borders in Europe. A dramatic story in three acts, October 2011.

[2] Poland obtained visa-free travel to Schengen countries on 8 April 1991. In March 1991 it had concluded readmission agreements.

[3] European Parliament press release, Vaclav Havel and Jerzy Buzek on the 20th anniversary of political change in Europe, 11 November 2009.

[4] Eurostat, "Substantial cross-European differences in GDP per capita", Statistics in Focus 47/2012, 13 December 2012.

[5] Council of the European Union, Council conclusions on EU-Turkey Readmission Agreement and related issues, JHA Council meeting in Brussels, 24/25 February 2011.

[6] Council of the EU, Council Conclusions on developing cooperation with Turkey in the areas of Justice and Home Affairs, Council document no. 11748/12, 21 June 2012.

[7] Roadmap towards a visa-free regime with Turkey, Annex II of the Note from the General Secretariat of the Council to the Permanent Representatives' Committee, Council document no. 16929/12, 30 November 2012.

[8] The agreement was initialled by the Turkish Ambassador to the EU and the head of the European Commission's Directorate-General for Home Affairs.

[9] ESI believes that this would be a wrong move and that there other, better solutions. See ESI's report "Saving visa-free travel. Visa, asylum and the EU roadmap policy", 1 January 2013.

[10] The question before the court in the Demirkan case is whether the freedom to provide services under EU-Turkey Association Law encompasses both providing and receiving services. If it does, Turkish tourists – as service receipients – would be entitled to travel to 11 EU member states without a visa.

[11] Visa-free travel means that a traveller is allowed to spend a total of 3 months within a 6-month period in the Schengen zone.

[12] The readmission agreement with Albania entered into force in 2006, but those with Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia became effective in 2008.

[13] European Commission, Evaluation of EU Readmission Agreements, COM (2011) 76 final, Brussels, 23 February 2011.

[14] Republic of Macedonia, Report on the measures and activities of the Government of the Republic of Macedonia under the Visa Liberalisation Monitoring Mechanism, 28 December 2012.

[15] Note from the (Danish) Presidency to the Council Working Party on Integration, Migration and Expulsion/Mixed Committee, Synthesis on Member States' practical experiences based on delegations' responses to a questionnaire discussed at the Working Party meeting on 1 February 2012, Council document 7260/12, 12 March 2012.

[16] See table 3, p. 14.

[17] 50th session of the Association Council, Statement by Egemen Bagis, Minister for EU Affairs and Chief Negotiator, Brussels, 22 June 2012.

[18] Ibid.

[19] See Annex C.

[20] Chechens from Russia and Azerbaijanis are discouraged to apply. See: Kemal Kirisci, "Turkey's New Draft Law on Asylum: What to Make of It?", in: Secil Pacaci Elitok and Thomas Straubhaar (eds.), Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities, Hamburg University Press, 2012, p. 66.

[21] 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, Article 1, paragraph B (1),

[22] Between 1995 and 2010 of almost 40,000 people who were resettled in this way 21,000 went to the US, 6,700 to Canada and 5,600 to Scandinavia. See: Kemal Kirisci, "Turkey's New Draft Law on Asylum: What to Make of It?", in: Secil Pacaci Elitok and Thomas Straubhaar (eds.), Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities, Hamburg University Press, 2012, p. 72.

[23] ESI interview with a former UNHCR Turkey lawyer, Brussels, April 2013.

[24] Data from the Turkish Ministry of Interior Affairs, used by Kemal Kirisci, "Turkey's New Draft Law on Asylum: What to Make of It?", see supranote 21, p. 71.

[25] European Commission, Regular report from the Commission on Turkey's progress towards accession, Brussels 1998, p. 44.

[26] Letter from Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu to Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom, Ankara, 16 January 2013.

[27] European Commission Memo, Joint statement by Commissioners Stefan Fule and Cecilia Malmstrom on the adoption by the Turkish Parliament of the law on foreigners and international protection, Brussels, 5 April 2013.

[28] UNHCR welcomes Turkey's new law on asylum, UNHCR Briefing Notes, Geneva, 12 April 2013.

[29] Current figures of Syrian refugees in Turkey can be checked at the UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response, Inter-Agency Information Sharing Portal.

[30] See: Excerpts from the EU roadmap, Annex.

[31] Juliette Tolay, "Turkey's ‘Critical Europeanization': Evidence from Turkey's Immigration Policies", in: Secil Pacaci Elitok and Thomas Straubhaar (eds.), Turkey, Migration and the EU: Potentials, Challenges and Opportunities, Hamburg University Press, 2012, p. 45.

[32] Juliette Tolay, ibid., p. 46.

[33] Source: Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2011.

[34] Hurriyet Daily News, "Consortium wins Istanbul airport tender for 22.1 billion euros", 3 May 2013.

[35] Hurriyet Daily News, "Istanbul hits decade-high in tourist numbers", 3 April 2013.

[36] Source: International Congress and Convention Association (2011).

[37] Letter from Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu to Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom, Ankara, 16 January 2013.

[38] Letter from Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom to Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, Brussels, 28 January 2013.

[39] Article 14 of the new law reads: "1) An airport transit visa regulation could be imposed on foreigners who want to transit Turkey. Airport transit visas are distributed by the consulates and are valid for 6 months. (2) Foreigners who are required to have an airport transit visa will be determined jointly by the Ministry [of the Interior] and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs."

[41] European Court of Human Rights, Judgment in the case of Eugenia Michaelidou Developments Ltd and Michael Tymvios v. Turkey, Application no. 16163/90, Strasbourg, 31 July 2003, paragraph 19.

[42] Council of Europe, Treaty Office, Protocol 4: chart of signatures and ratifications, as of 17/05/2013.

[43] Protocol 7 from 1984 stipulates procedural safeguards relating to expulsion of aliens (Art. 1), the right of appeal in criminal matters (Art. 2), the right to compensation for wrongful convictions (Art. 3), the right not to be tried or punished twice (Art. 4), and equality between spouses (Art. 5).

[44] Council of Europe, Treaty Office, Protocol 7: chart of signatures and ratifications, as of 17/05/2013.

[45] Letter from Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu to Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom, Ankara, 16 January 2013.

[46] Letter from Home Affairs Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom to Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, Brussels, 28 January 2013.

[47] Draft Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Turkey on the Readmission of Persons residing without Authorisation, 14 January 2011, Article 24, paragraph 3.

[48] Draft Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Turkey on the Readmission of Persons residing without Authorisation, 14 January 2011, Article 24, paragraph 3.

[49] According to the website of the Turkish Foreign Ministry, section "Turkey's fight against illegal migration" (translated from Turkish), Turkey has concluded readmission agreements with the following countries: Bosnia-Herzegovina (2012), Greece (2001), Kyrgyzstan (2003), Moldova (2012), Nigeria (2011), Pakistan (2010), Romania (2004), Russia (2011), Syria (2001), Ukraine (2005) and Yemen (2011).

[50] In 2012, Greek authorities apprehended 11,136 Pakistanis and 7,927 Syrians in Greece, most of whom will have come from Turkey. See website of the Hellenic Police, Nationality of irregular migrants apprehended by the police and port authorities for illegal entry and residence in 2012.

[51] This is one of the initiatives that the Commission has proposed as part of an EU-Turkey "Broader dialogue and cooperation framework on Justice and Home Affairs." Note from the General Secretariat of the Council to the Permanent Representatives' Committee, Council document no. 16929/12, 30 November 2012.

[52] Joint Declaration on Technical Assistance, Draft Agreement between the European Union and the Republic of Turkey on the Readmission of Persons residing without Authorisation, 14 January 2011.

[53] Previously irregular migrants were simply given an order to leave the country within 4 weeks and then let go. Now Greek police detain them for up to six months where facilities are available. The detention period can be even extended to 18 months. From a human rights perspective, the long detention periods and bad conditions in the detention centres are problematic. For more information, read: UN Office for Human Rights, UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants concludes the fourth and last country visit in his regional study on the human rights of migrants at the borders of the European Union: Greece, 3 December 2012.

[54] The data until 2010 is from Frontex, which states that almost all irregular crossings into Greece are detected. Frontex' "Press Pack May 2011," p. 9, at; Frontex Annual Risk Analysis 2012, April 2012, p. 14, at); Frontex Annual Risk Analysis 2013, April 2013, at. Since Frontex does not provide separate figures for Greece's borders in 2011 and 2012, we used figures from the Hellenic Police (whose data for earlier years is largely the same as Frontex'), at.

[55] Website of the Hellenic Police, Arrests of irregular migrants at the Greek-Turkish land border oer month for the years 2011 and 2012 (in Greek). The trend continues. In January 2013, 146 irregular migrants were apprehended at the Greek-Turkish land border; in February 2013: 16; and in March 2013: 43. Website of the Hellenic Police, Arrests of illegal migrants at the Greek-Turkish land border per month for the years 2012-2013 (in Greek).

[56] Website of the Hellenic Police, Irregular migrants apprehended by police and port authorities for illegal stay and entry at the border, 3 months 2012/3 months 2013 (translated from Greek; data is in Greek).