Beyond the silent cash-machine – smart solidarity

Dear friends,

One week ago, a new ESI report – The wizard, the virus and a pot of gold – Viktor Orban and the future of European solidarity – put a spotlight on the future of European solidarity.

The EU faces three major crises today. One is a public health crisis, which threatens hundreds of thousands of lives. One is an unprecedented economic and social crisis, which puts at risk the employment and livelihoods of tens of millions of Europeans. And then there is a crisis of core values that underpin the European project: the rule of law and the checks and balances of liberal democracy. These are under attack today from inside and outside the Union.

The challenge is to tackle these crises in a coherent way. While Europe needs more solidarity and financial transfers, these must strengthen the values that connect Europeans, not undermine them.

To this end the EU should make future solidarity conditional on respect for the rule of law. Implementing all Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) judgements related to the rule of law should be a precondition for receiving funding. Building on a Commission proposal from 2018, the Commission and the European Parliament should also be able to recommend reducing transfers in case of violations, unless a qualified majority in the Council rejects this.

If member states threaten to veto this overdue reform, others should threaten that they would move ahead as a coalition of member states through enhanced cooperation, leaving those unwilling to join outside – and unable to benefit.

Essay on EU solidarity in Der Spiegel "The language of money"

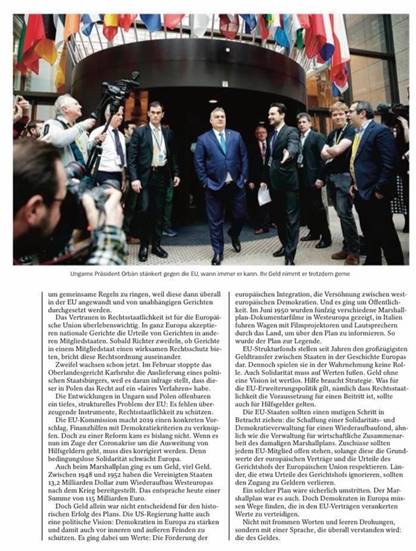

Orban: the EU as oppressive Empire

"Today it is written in the book of fate that hidden, faceless world powers will eliminate everything that is unique, autonomous, age-old and national. They will blend cultures, religions and populations, until our many-faceted and proud Europe will finally become bloodless and docile. And if we resign ourselves to this outcome, our fate will be sealed, and we will be swallowed up in the enormous belly of the United States of Europe."

"Only our own national independence can save us from the all-consuming, destructive appetites of empires. The reason we stuck in the throat of the Soviet empire and the reason it broke a tooth when it tried to bite on us was that we asserted our national ideals, that we stood together and did not surrender the love of our homeland. This is also why we shall not accept the EU's transformation into a modern-day empire. We do not want them to replace the alliance of free European states with a United States of Europe."

"The members of this alliance are the Brussels bureaucrats and their political elite, and the system that may be described as the Soros Empire. This is an alliance which has been forged against the European people"

Parasitic membership

The European Union is not an Empire. 27 democracies decide, voluntarily, to share sovereignty. They conclude that this is in their national interest. They agree to do this based on rules and values, embedded in the Treaty on European Union. Any one of the 27 members can decide to leave the Union. This happened in 2020. It was painful, but it is not an existential threat.

What is an existential threat to the EU are members who remain, but work purposefully to destroy the values that hold it together. Such members need to be confronted with the tools the EU has: political arguments, legal actions and money.

Article 2 of the Treaty on the EU states that the EU is "founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities." But what happens when the government of one of the EU's 27 member states undermines the rule of law and democracy?

As the European Union is not an Empire, it cannot – fortunately – enforce its rules by force. At the same time, the EU is unable to expel a member state, whatever happens.

However, once a member state government takes an a la carte approach to the rule of law, the basis for solidarity disappears: if some do not abide by the rules that bind all, why should others? In this way the bond that ties members together dissolves: the belief that all members of the EU remain fully committed to the values of the Treaty. This belief is of existential importance. It needs to be defended and the EU has a vital self-interest in doing so.

So how can the EU react to a government that decides it no longer shares the core values of the EU, but choses to remain inside, working to undermine these rules; that pursues the project of turning a union of liberal democracies into a loose association of different types of regimes, liberal and illiberal, democratic and autocratic, those with independent courts and those without?

Such a project involves deception. Governments pursuing it will present the EU as an oppressive empire, not a voluntary union. They will build coalitions with others, inside and outside, who have an interest to weaken the EU. They will argue that nobody knows what the "rule of law" means and that a "democracy" does not need to be liberal. And that in any emergency – and there seems to be one all the time, whether it is a financial crisis, migration, a "cosmopolitan conspiracy" or a virus – checks and balances must be curtailed.

This is the threat: member state governments that embrace autocratic regimes as their inspiration, then proceed to undermine the rule of law in their own countries; that turn public broadcasters into propaganda channels, then vilify all opposition and civil society as enemies of the people; and that continue, while doing so, to enjoy the benefits of membership. This is parasitic membership, the opposite of solidarity.

Threat one: Poland and the CJEU

ESI has written several reports on the deep crisis of the rule of law in Poland. Recently the situation has deteriorated further.

On 9 October 2019, the European Commission took Poland to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) in Luxembourg, arguing that the new disciplinary regime for judges undermined the independence of courts and violated the Treaty on European Union:

"Polish law allows to subject ordinary court judges to disciplinary investigations, procedures and ultimately sanctions, on account of the content of their judicial decisions. Also, the new disciplinary regime does not guarantee the independence and impartiality of the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court which reviews decisions taken in disciplinary proceedings against judges."

On 14 January 2020, the Commission also requested that the CJEU issue an order to halt all judicial activities by the Disciplinary Chamber:

"The [Polish] Supreme Court stated that the Disciplinary Chamber does not meet the requirements of EU law on judicial independence and is therefore not an independent court within the meaning of EU law and of national law. Despite the judgments, the Disciplinary Chamber continues to operate, creating a risk of irreparable damage for Polish judges and increasing the chilling effect on the Polish judiciary."

On 8 April 2020, the CJEU agreed in a ruling: "Poland must immediately suspend the application of the national provisions on the powers of the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court with regard to disciplinary cases concerning judges."

Poland was given a month, until early May 2020, to inform the European Commission how it would enforce the judgment. The Disciplinary Chamber rejected the judgement immediately, arguing that this issue was "not the responsibility of the European Union, but constitutionally belonged to the sphere of sovereign decisions of a Member State." Deputy Justice Minister Sebastian Kaleta argued that the CJEU decision was "an usurpation violating Polish sovereignty": "This judgment is not, in fact, within the framework of the powers conferred on the European Union, because the European Union simply does not have the authority to assess the legality of constitutional bodies in a member state."

Is the Polish government ready to reject the decision of the CJEU, on an issue of fundamental importance, thus cutting Poland off the European legal order? It would be an unprecedented escalation, and a moment of truth for the whole EU.

Threat two: the virus and Hungarian democracy

In September 2018 the European Parliament voted, by a large majority (448 votes to 197), to trigger the Article 7 procedure against Hungary, for eroding democracy and failing to uphold fundamental European Union values. The Hungarian government dismissed this and went on the attack. In late 2019 it accused other EU governments concerned about these issues of being manipulated by a man who, it alleged, wanted to destroy the Hungarian nation: George Soros. It even referred to other EU governments as "the Soros orchestra."

In January 2020 the European Parliament concluded, by a large majority (446 votes to 178), that "the situation in both Poland and Hungary has deteriorated since the triggering of Article 7." Again, nothing happened.

Then, on 30 March, Viktor Orban's majority passed a new law in the Hungarian parliament: the Protection Against the Coronavirus Act. This law allows Orban to rule by decree in a "state of danger" without any time limit. It also created new crimes: persons who "distort the truth" in relation to the corona emergency face up to five years in prison, intimidating local officials, doctors or ordinary citizens.

Hungarian leaders brushed all criticism aside. When the secretary general of the Council of Europe warned that an indefinite state of emergency could not guarantee basic principles of democracy, Orban told her to shut up. When leaders of member parties of the European Peoples Party (EPP), to which Orban's party still belongs, and including two European prime ministers, warned that this Coronavirus Act is a violation of the founding principles of liberal democracy, Orban's response was curt: "I have no time for this!" When the foreign minister of Luxemburg warned that the EU could not accept a "dictatorial government" in a member state, the Hungarian foreign minister described critics as lying hypocrites "spreading fake news."

Does criticism matter? Does the Article 7 procedure make any difference? Are there ever any consequences? Not in the current system.

The big, silent cash-machine

Neither the government in Warsaw nor the one in Budapest worried too much about criticism. They had few reasons. On the same day that the Coronavirus Act was adopted in the Hungarian parliament, 30 March, the EU adopted a Coronavirus Response Investment Initiative to mobilise € 37 billion to support member states deal with the corona crisis.

Italy was then the country most affected by the coronavirus, with more than 9,100 deaths on 27 March. Hungary had 10. Yet of these € 37 billion Italy was allocated funding equivalent to 0.1 percent of its GDP; Spain 0.3 percent; Poland 1.4 percent; and Hungary 3.9 percent of its GDP, a remarkable € 5.6 billion.

The European Commission admitted that this was not "an optimal allocation." It was, however, a perfect allocation for Viktor Orban.

ESI highlighted this issue in the Pot of Gold report. Der Spiegel, the Financial Times, and the New York Times reported on it. Then the Hungarian government responded. Its response was telling.

Zoltan Kovacs – Balas Hidveghi

On 20 April secretary of state Zoltan Kovacs, wrote:

"Now, don't get me wrong, the math adds up behind the insidious conclusion that, in terms of its annual GDP, Hungary would receive seven times as much money from the EU than Italy. In this case, however, it's not about the math … The European Commission, in fact, has not given a single euro of extra support to Hungary for the defense against the coronavirus compared to what was already agreed upon in the 2014-2020 EU budget. To put it simply: What's been granted to Hungary within the framework of CRII would have been paid out anyway, regardless of the coronavirus epidemic."

The argument, in short: This is our money. Hungary deserves to get more than Italy. To suggest otherwise is insidious. As Kovacs notes, most of these billions were allocated to Hungary in 2013, when EU member states settled on a seven-year budget. Hungary was then granted € 25 billion, or 17 percent of its GDP. Viktor Orban explained at the time that this amounted to six railway wagons full of 20,000 Hungarian Forint [€ 56] banknotes. It is also more money than the €14 billion that Germany received from the US under the Marshall Plan [in 2018 value].

Poland was granted € 86 billion in 2013, or 16 percent of its current GDP. This is more than twice the €30 billion that the United Kingdom received from the US under the Marshall Plan.

US Marshall Plan aid (billion €, 2018 value)

|

Total 1948-1952 |

per year |

|

|

UK |

30 |

7.5 |

|

France |

26 |

6.5 |

|

Italy |

14 |

3.5 |

|

Germany |

14 |

3.5 |

|

Netherlands |

10 |

2.5 |

EU structural funding per year (billion €)

|

Total 2014-2020 |

per year |

|

|

Hungary |

25 |

3.6 |

|

Poland |

86 |

12.3 |

|

Romania |

31 |

4.4 |

|

Greece |

21 |

3.1 |

|

Spain |

40 |

5.7 |

|

Italy |

45 |

6.4 |

There are, of course, good economic arguments for generous structural funds and regional policy in a single market. There are no good arguments that such funding should not also require recipient countries to respect the rules of the Union which provides them. And there are no arguments at all not to challenge governments in these countries when they argue that there is no EU solidarity.

A leading MEP from Orban's party, Balas Hidveghi, explained recently:

"Instead of helping the fight against the coronavirus, Brussels is again preoccupied with Hungary. It is insulting the rule of law in Hungary, it is spreading lies, it does not give us support, on the contrary, it [the CJEU] has recently condemned us in the case of compulsory asylum quotas."

This is a consistent line of the Orban government: While it receives 3.9 percent of its GDP in EU transfers, it accuses the EU of failing to provide any help. And while it complains that the EU does nothing, it praises China and Uzbekistan (!) as true friends. Meanwhile the EU pays, like a big and silent cash-machine.

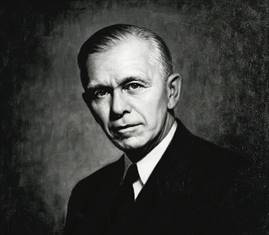

Marshall and the future of EU solidarity

To put existing European solidarity in perspective let us compare it to the most famous international assistance in European history. Between 1948 and 1952 the United States dedicated $ 13.2 billion to the Marshall Plan to reconstruct Western Europe after the war. $ 13.2 billion would be worth around € 125 billion in 2018 money – € 7.5 billion per year for the UK; € 6.5 billion per year for France; € 3.5 billion per year for Italy and Germany; and € 2.5 billion per year for the Netherlands. This assistance lasted for four years.

The Marshall Plan's objective was to protect democracies from their internal and external enemies. It reflected a geopolitical vision: to foster European integration, to strengthen cooperation and to promote reconciliation between West European democracies. It was controversial: communist parties in both Italy and France opposed it. So did Stalin's Soviet Union.

George Marshall and a legendary policy

Proposing generous US support for European recovery in a speech, as George Marshall did at Harvard in June 1947, was one thing; persuading the US public and Congress to fund it was another. As Marshall put it himself: "I flew thousands of miles a week … I worked on it as hard as though I was running for the Senate or the presidency … it was a struggle from start to finish." Allen Dulles, the head of the private Committee for the Marshall Plan, which set out to convince the US of the wisdom of this effort, explained in 1947 that if the US would concentrate "aid on those countries with free institutions" the "common cause of democracy and peace" would be promoted. This was "not a philantropic enterprise … It is based on our views of the requirements of American security."

To reach this strategic – and political – objective the administrators of the Marshall Plan also made an effort to ensure that the plan's impact was visible. As Greg Behrman wrote in his book "The Most Nobel Adventure":

"In June 1950, fifty different Marshall Plan documentary films were being shown to people across Western Europe through commercial and non-commercial distributors; another sixty were in production. To reach Italians in the countryside, ECA [the Economic Cooperation Administration, running the plan] sent trucks equipped with movie projectors, loudspeakers and portable displays to tell the ERP [European Recovery Programme] story."

On 5 April Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called for a new "Marshall Plan" for Europe and for more solidarity to strengthen the European Union. This is the right inspiration.

However, it was not the amount of funding but the combination of visibility, political focus, inspiration and competent administration that turned the Marshall Plan into a legend.

The European Union needs to develop new forms of solidarity. to live up this this example. It must stop being a silent cash-machine.

Recovery grants (and all future structural funds) should be open to every European Union member committed to respecting the values of the European treaties. Countries refusing to implement judgements of the Court of Justice of the European Union relating to core values and the rule of law should not receive funding. At the same time, a mechanism is needed, building on the Commission proposal from May 2018, to allow both the European Commission and the European Parliament to propose sanctions in case of serious violations of core values.

But what should happen in case some member states block such reforms, threatening a veto? After all, the reluctance of some explains why this debate has not led to any concrete results in almost a decade.

In that case other member states should not give up. Too much is at stake this time. They should instead consider a bold step: the creation of a Solidarity and Democracy Administration (SDA), a reconstruction fund separately administered for the post-corona recovery effort, with a structure similar to the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) that the US set up to administer the Marshall Plan.

Already in 2013, the political scientist Jan-Werner Müller asked, in a prophetic paper: "Could there be a dictatorship in the EU?" And: "Should Brussels somehow step in to save, or, for that matter, revive democracy?" He referred, already then, to "recent developments in Hungary." Since then the EU has not developed any more effective instruments.

What the EU needs now is a strategy that simultaneously addresses threats to economic cohesion and to democracy. It needs ways to defend the values enshrined in the EU treaty. And pious words and empty threats are not enough; the EU will also need to speak the language of money.

Best regards,

Gerald Knaus

Further reading

ESI report, The wizard, the virus and a pot of gold – Viktor Orban and the future of European solidarity, 18 April 2020

ESI discussion paper, Poland's deepening crisis - When the rule of law dies in Europe,14 December 2019

ESI report, Under Siege – Why Polish courts matter for Europe, 22 March 2019

ESI Newsletter, Dark twins – Viktor, Matteo and the Drowning of Europe, 16 August 2018

ESI Background Paper, "On the brink of victory" – Viktor Orban, rhetorical poison and a vision of hell, 15 June 2018

ESI report, Where the law ends. The collapse of the rule of law in Poland – and what to do, 29 May 2018

The Economist, The wizard of Budapest, 8 October 2016

ESI Newsletter, The most dangerous Wizard in the EU, 7 October 2016

ESI Newsletter, Refugees as a means to an end – The EU's most dangerous man, 24 September 2015