Coup de grâce – Delors and squaring the circle – Norway in the Balkans

This newsletter is also available in French:

Le coup de grâce – Delors et la « quadrature du cercle » – La Norvège dans les Balkans

Dear friends,

Last week the European Council refused to open accession talks with North Macedonia, the best prepared Western Balkan candidate since this process was launched in Zagreb nineteen years ago.

North Macedonia applied for EU membership in March 2004. In April that year its Stabilisation and Association Agreement came into force, ten months before Croatia's.

In December 2005 North Macedonia was granted candidate status. Five years before Montenegro, six years before Serbia and eight years before Albania.

In October 2009 the European Commission proposed to open accession talks with North Macedonia. It did so again in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2018 and 2019 (in 2015 and 2016 it recommended opening talks linked to conditions). The most recent recommendation was backed by the European Parliament and the president of the European Council, Donald Tusk.

Just in the past two years the following happened in North Macedonia:

- In April 2017 for the first time a member of the Albanian minority became speaker of Parliament.

- In August 2017 North Macedonia signed a friendship treaty with neighboring Bulgaria.

- In June 2018 North Macedonia resolved its name dispute with Greece in Prespa.

- In January 2019 North Macedonia changed its constitution, in line with the Prespa Agreement.

- In January 2019 Albanian became the second official language in North Macedonia.

In May 2019 the European Commission compared the level of preparedness for EU membership across the Western Balkan region. It assessed all chapters and key reform areas, from statistics to procurement, from the rule of law to freedom of expression, and found that North Macedonia was doing as well as Montenegro (negotiating since 2012) and better than Serbia (negotiating since 2014) before even opening negotiations.

See here: 2019: North Macedonia vs Serbia, how they are doing

If opening accession talks would be a matter of merit, talks with North Macedonia would have been opened a long time ago. But is it? Was it ever?

Picadors of Balkan accession

A picador wounding the bull

The Western Balkan accession process has been in crisis for a very long time. Like picadors, the horsemen who jab and wound the bull before the matador even appears, many have played a role in undermining the credibility and effectiveness of this policy, in the EU and in the Balkans.

Five years ago, in November 2014, then Serbian deputy prime minister Kori Udovicki and ESI invited European diplomats to a briefing in Belgrade. The topic: the crises of the Balkan accession process, and possible ways to respond.

ESI Belgrade presentation, November 2014

The presentation focused on three troubling facts:

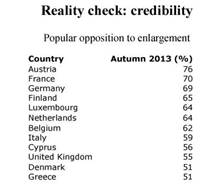

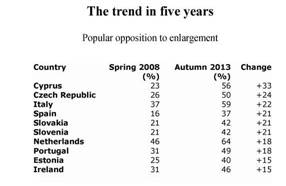

1. EU accession policy was increasingly unpopular. Following 2008 there had been a sharp increase in opposition to enlargement across the EU.

A policy as unpopular as this is vulnerable to some member states opposing it. This was not fatal in the short term. And yet, some strategy was needed to reverse this trend: to also convince French, Dutch and German citizens that this policy was, in fact, in their interest, too.

2. EU accession policy was not transformative. Already in 2014, the European Commission found little evidence that the accession process made reforms more likely. This raised a worrying possibility: that countries might regress while negotiating accession.

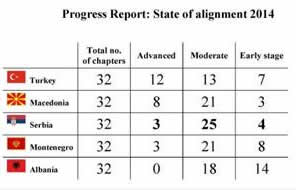

3. EU accession policy was not fair. The opening of talks and the opening of "chapters", always requiring unanimity among all EU member states, was not based on merit. Already in 2013, the European Commission reports found that North Macedonia was more advanced than both Montenegro and Serbia. But it was subject to a veto.

ESI also found that the "chapter methodology" structuring negotiations was deeply flawed. There was a lot of politicking around opening each chapter, though few understood what it actually meant.

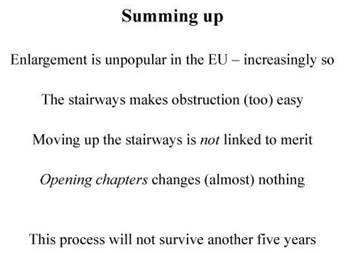

The whole process resembled a stairway of more than 70 steps, with national vetoes at each step. Opening a chapter did not reflect progress made in any particular area. It also did not make further progress in this area more likely. The Commission's own assessment confirmed this, year after year.

In November 2014 we summed up our warning in Belgrade in one slide:

This was not a difficult prediction to make: A process that is unpopular, not transformative and not fair was not going to survive forever without challenge.

It didn't. In the past five years these concerns have grown. There have been reforms in Albania and North Macedonia, eager to begin talks, inspired by the vision of accession. However, for countries already negotiating, the absurdity of the chapter approach has been demonstrated again and again. The lack of a clear reachable goal has also been deeply demoralizing, both for alleged laggards (Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo) and for alleged frontrunners (Montenegro, Serbia).

The absence of movement

Take one area of reform, important for fighting corruption, to grasp the problem: public procurement. In 2015 the European Commission found that North Macedonia was on the same level as Montenegro and Serbia in the field of public procurement:

European Commission – assessments in October 2015 Progress Reports

|

Chapter |

Turkey |

North Macedonia |

Serbia |

Montenegro |

Albania |

|

Public procurement |

"Turkey is moderately prepared on public procurement." |

"The country is moderately prepared in this area." |

"Serbia is moderately prepared in this area." |

"Montenegro is moderately prepared on public procurement." |

"Albania has some level of preparation in public procurement." |

The scale used by the Commission for the level of preparedness is as follows:

Well advanced

Good level of preparation

Moderately prepared

Some level of preparation

Early stage

North Macedonia did not open accession talks. Montenegro and Serbia did. Both also "opened" the procurement chapter: Montenegro in December 2013 and Serbia in December 2016.

What happened then? According to the Commission, neither Montenegro nor Serbia have progressed since opening this chapter, many years ago. Opening a chapter made no difference at all. Nor is it clear, for observers, what is missing. This means that there is little accountability. North Macedonia remains on the same level as the "frontrunners." What is missing for all six countries: a clear roadmap, listing all requirements in this field to become an EU member, and where they stand.

European Commission – assessments in May 2019

|

Chapter |

Turkey |

North Macedonia |

Serbia |

Montenegro |

Albania |

|

Public procurement |

"Turkey is moderately prepared for public procurement." |

"The country remains moderately prepared in this area" |

"Serbia remains moderately prepared on public procurement." |

"Montenegro remains moderately prepared on public procurement." |

"Albania has some level of preparation in public procurement" |

This lack of progress in "open chapters" is not surprising. In 2014 ESI warned that "opening chapters" did not help reforms: it was political theatre. Already then, the disheartening Turkish experience confirmed it:

"In summer 2013 there was a heated debate in Turkey and in the EU whether to open a new chapter after many years in which none were opened: Chapter 22 (regional policy). There were many statements by politicians about how important this would be … The German government, on the other hand, insisted on delaying the opening until after summer 2013. In the end chapter 22 was formally opened in the autumn. Leaders – and international media – spoke about this as if something significant had happened (Die Welt: "Accession talks gain new momentum")

"In fact, following a meeting – the so-called Intergovernmental Conference – when it was declared that Chapter 22 was now "open", nothing else happened. There was no additional meeting. There was no additional funding. There was no additional impetus for reform. The "opening" was political theatre, for one day. It had no link to merit, criteria, or progress. Ultimately it made no difference." (ESI 2014)

We repeated our warning in May 2017 in "The Chapter Illusion" It remains unaddressed.

All this raises an obvious problem: if opening chapters is political theatre and yet the central element of the accession process, then the whole process becomes theatre. If it does not inspire measurable change, and leaves unclear what still needs to be done, what is the point?

It is obvious by now that opening accession talks did not lead to measurable progress in Turkey (negotiating since 2005!) or Serbia (negotiating since 2014). Why would this be different in the future in North Macedonia, Albania or Bosnia and Herzegovina?

The Hungarian vision of enlargement

Orban plotting a different accession process

One European leader has, in fact, long questioned the wisdom of linking enlargement to progress, as assessed by the European Commission: Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban. When the European Commission was critical of North Macedonia under its previous prime minister, Nikola Gruevski, Orban praised Gruevski in September 2017 as a model leader. When the European Commission noted that Serbia needed to make more progress on the rule of law in April 2019 Orban's foreign minister declared that, if it were up to Hungary, Serbia might join the EU immediately:

"You deserve to become member of the European Union as soon as possible. If it was up to us, you would be member of the European Union already tomorrow."

Already in 2014 Orban pushed for a Hungarian to get the enlargement portfolio in the Commission in order to change the EU's approach. Then, when candidates for the next commission were presented on 10 September 2019, Orban saw his wish granted. Orban is open about why he is so keen on a Hungarian enlargement commissioner. He explained in Baku on 15 October 2019 that with a Hungarian in charge criticism would be toned down, and both Turkey and Azerbaijan could look forward to much better relations with the EU:

"Our chances are not bad, but this is a keen battle. If we manage to obtain (it), then we will have close cooperation with Azerbaijan on the issue of the Eastern partnership, and with Turkey regarding membership talks, we will be happy to be at your disposal to help you with your aspirations."

Coup de grâce à la française

In the end, however, it was not Viktor Orban, but Emmanuel Marcon who delivered the coup de grâce to this process.

Already in April 2018 French president Emmanuel Macron warned the European Parliament:

"I don't want a Balkans that turns toward Turkey or Russia, but I don't want a Europe that, functioning with difficulty at 28 and tomorrow as 27, would decide that we can continue to gallop off, to be tomorrow 30 or 32, with the same rules."

In May 2018 Emmanuel Macron noted at the EU Western Balkan summit in Sofia:

"What we've seen over the past 15 years is a path that has weakened Europe every time we think of enlarging it. And I don't think we do a service to the candidate countries or ourselves by having a mechanism that in a way no longer has rules and keeps moving toward more enlargement."

Then, last Thursday evening in Brussels, Emmanuel Macron explained French opposition to opening accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania. Macron made three main points:

- The French Non was not about North Macedonia or Albania, whose leaders had taken "courageous" steps. It was about the EU's future. The EU, Macron explained, is not prepared to admit any new members. It is unable to take difficult decisions. To have even one country join, in five or ten years, would weaken it: "It does not work well with 27, so how can one explain that it will work better with 28, 29, 30, 32?"

- The received wisdom among many member states, that opening accession talks strengthens EU influence, is not convincing. Nor is the argument that it inspires reforms. Macron, who visited Belgrade three months earlier "invited people to see this for themselves in countries which had already opened accession talks."

- Opening talks with some Western Balkan countries, and not with others, risked creating tensions in the region and would be a "terrible policy." It would be wrong to open talks with North Macedonia but not with Albania. He noted that other countries agreed with this.

Macron challenged what he called the "teleology of enlargement": the notion that the Western Balkan had a European destiny. Offering "every neighbour accession", Macron noted emphatically, was "bizarre." This was not the Europe France wanted.

So what now? For two decades EU policy and influence in the Western Balkans were based on the promise of eventual accession, a promise repeated in countless Council conclusions. Macron himself promised in September 2017 at the Sorbonne:

"When they fully respect the acquis and democratic requirements, this EU will have to open itself up to the Balkan countries, because our EU is still attractive; and its aura is a key factor of peace and stability on our continent."

But what might France support? In Brussels last week Macron was vague about concrete alternatives; the EU, he noted, "might open something."

Delors and squaring the circle

Where to find inspiration

It is now obvious to everyone in the Balkans that any European Council conclusion, any promise made today, will not bind future EU governments. Why would Serbia and Kosovo make painful compromises if they cannot be sure of ever joining? Why would Bosnians, if this would not guarantee any progress? Why would anyone trust in a process that is not about merit?

Can last week's outcome still be corrected? It would, obviously, be a powerful signal to open accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania. But it is not likely, would not be enough to reverse the collapse of trust, and would not restore the credibility of the process for any of the other four Balkan countries. It would come too late.

So might the EU replace the promise of accession with a "junior partnership", "membership light" or "privileged partnerships"? Such proposals would certainly backfire, adding insult to injury. They would not increase EU influence. Nor would another round of talks, even moderated by the most gifted envoys, on issues that proved hard to resolve even when EU accession was more credible, be very promising.

Macron's circle must be squared. It is clear today that the consensus that further enlargement is inevitable (Macron's teleology) has broken down. It is also clear that excluding future enlargement and walking away from a promise made by countless European Councils would be hugely divisive. Many EU members care a lot about Balkan stability. If Macron wants a strong, cohesive EU, then France must find a way to bridge this gap.

What is needed is a process that does not replace accession and yet is different; a process that promises EU influence and is also attractive and credible to Balkan publics and leaders; a process that promises benefits, not in the distant future but from the very beginning. Such a process is possible. It is not a utopia, not an untested idea, but something that exists already and can be adapted. To see how we need to be inspired by a great French politician, and by the experience of Europe's North.

Such a process was conceived by a great European statesman, former Commission president Jacques Delors. In January 1989, Delors told the European Parliament in Strasbourg:

"As far as the 'other Europeans' are concerned, the question is quite simple: how do we reconcile the successful integration of the Twelve without rebuffing those who are just as entitled to call themselves Europeans?"

He proposed a "new, more structured partnership … to highlight the political dimension of our cooperation in the economic, social, financial and cultural spheres." Out of this idea grew an offer to non-EU members to join the single market, in a European Economic Area (EEA).

The EEA entered into force in January 1994. It aimed to create a "homogeneous European Economic Area." The EEA is based on four freedoms – the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital; along with competition, state aid, consumer protection, environment, statistics, and other areas. The EAA is a form of "quasi-membership." More than 12,500 EU legal acts have been incorporated into the EEA agreement since 1992.

The EEA is certainly demanding. The section on "environment" in the agreement consists of three short articles stating broad aims: "to preserve, protect and improve the quality of the environment; to contribute towards protecting human health; to ensure a prudent and rational utilization of natural resources." All action should be "based on the principles that preventive action shall be taken, that environmental damage should as a priority be rectified at source, and that the polluter should pay." Then one sentence refers to an annex of sixty-six pages, covering water, air, waste, noise and many other issues, listing decisions, directives, regulations. It is an obvious to-do list for any Western Balkan country that wants to move closer to the EU. And if any does, it would be in the EU's interest to support it financially, with grants and investments.

Norway benefits from and pays for this access: per capita, Norway's contribution to EU policies is almost as high as Germany's. And it also benefits the EU. The European Commission noted in a review 20 years after the signing of the agreement that it "has provided the bedrock for very good and close EU relations with the EEA EFTA countries over the past two decades."

Crucially, EEA accession also prepared countries for accession at a later stage. A former chief negotiator of Finland wrote that "the EEA greatly facilitated our accession negotiations." A former negotiator of Sweden, confirmed:

"For my country, Sweden, it was a stepping-stone towards full membership of the EU. Without the EEA Agreement, and the process leading up to it – the best European Integration School that I can think of – we would not have been able to conclude our accession negotiations so easily and rapidly as was the case. It was like starting a marathon run at the 25 km mark!"

This would not be the end of the promise of accession, nor an acceleration. It would give Western Balkan reformers and the European Commission a clear roadmap. It squares the circle.

Norway in the Balkans

From Scandinavia to the Balkans

This, then, is a bold and realistic vision for 2020 and the next European Commission, for the Croatian and German EU presidencies.

The EU should offer all six Western Balkan nations the possibility to join the single market, like Norway and Iceland. It should radically reform the methodology of assessing progress.

Would this be an attractive offer? The EEA covers all key areas that matter to potential investors. It sets out European standards. It sends a strong signal to citizens that, eventually borders and isolation will be overcome. The EU should increase resources for the Western Balkans to make all this more attractive. This would help the EU assert influence in a region that all together has less than half the GDP of Romania and is surrounded by EU members. A region that also saw four wars in the decade before the EU promised integration in Zagreb in 2000.

This relationship does not guarantee future accession – nothing today can. But neither is it a junior partnership that excludes future accession. It makes any future debates on membership more credible, when the time comes. It does not punish Serbia or Montenegro: any progress they made so far only means that they are closer to getting in. It does not exclude Albania, North Macedonia or Bosnia and Herzegovina. And it can be opened to Kosovo too, as a status neutral way to ensure convergence with its neighbors, including Serbia. It avoids the division of the region that Macron fears. All countries get the same chance. Progress is decided based on reforms, measured by the same standards.

In early 2020 the European Commission and member states should jointly draw up roadmaps listing the key requirements in key sectors that Norway (or Iceland) are meeting today. Instead of "opening of chapters", comprehensive public roadmaps would be offered to all six countries. Progress would be regularly assessed seriously and objectively across all countries, best in joint teams of experts, led by the European Commission but including member state experts. These two institutions need to cooperate to assess progress in detail, to speak with one voice. There would be no demotivating vetoes, however, publics in the Balkans could compare progress as in a race: Serbia might prove to everyone that it truly has the best administration in the region; Kosovo might overtake Serbia in one field; North Macedonia and Albania could compete on meeting the environmental acquis. It would lead to a healthy competition.

This would increase EU influence. By committing to the rules of the single market the influence of outside actors, China or Russia, would be subject to the same constraints in the Western Balkan as in the EU.

And everything should be combined with financial rewards: "more for more", grants and investments for countries that do well in administrative and legal reforms in any one sector, objectively assessed. Bilateral donors could also reward performance in this way.

This would require credible rule of law reforms to work. Countries that violate fundamental human rights or threaten their neighbors could be excluded or suspended – the reversibility Macron has called for. And it could be launched at the Zagreb summit in May 2020 with all six countries under the Croatian EU presidency.

Once progress in the Balkans becomes visible, the popularity of accession might also increase. In fact, things are not hopeless in this regard, as a comparison of two polls (2013 and 2019) shows:

Popular opposition to enlargement, in percentage (Eurobarometer, 2013 and 2019)

|

2013 |

2019 |

|

|

Austria |

76 |

57 |

|

France |

70 |

58 |

|

Germany |

69 |

57 |

|

Finland |

65 |

52 |

|

Netherlands |

64 |

60 |

|

Luxembourg |

64 |

53 |

|

Belgium |

62 |

56 |

|

Italy |

59 |

41 |

|

EU |

52 |

42 |

|

Greece |

51 |

44 |

|

Denmark |

51 |

50 |

The demise of the current accession policy is a threat to EU influence, in a critical region, at a critical moment of global uncertainty. It was profoundly unfair to the government in Skopje. But it can be a chance for something more credible, fair and transformative.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

Further reading:

How are they doing in 2019? European Commission assessments of Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Albania (May 2019) (29 May 2019)

Wine, dog food and Bosnian clichés – False ideas and why they matter (5 November 2017)

The Chapter Illusion – For honesty and clarity in EU-Turkey relations (15 May 2017)

Escaping the first circle of hell or the secret behind Bosnian reforms (10 March 2016)

A reporting revolution? Towards a new generation of progress reports (November 2015)

Newsletter: Accession revolution in Brussels – a new flagship – Usain Bolt and the quality of statistics (9 November 2015)Paris Paper: Enlargement and Impact – Twelve ideas – Dummy Report (January 2015)

Enlargement 2.0 – The ESI Roadmap Proposal (Belgrade) (27 November 2014)

An effort of persuasion – Chronology of ESI activities (November 2015)

Vilnius Handout: Why a new generation of progress reports is needed (September 2014)

Video: Enlargement and the benefits of competition (26 February 2014)

Enlargement reloaded – ESI proposal for a new generation of progress reports (31 January 2014)

How (not) to compare countries

Trust in Numbers – Eurostat and comparing statistics (19 March 2015)

Rankings that fail – Doing Business, Bosnia and Macedonia in 2015 (9 November 2015)

Measuring corruption – The case for deep analysis and a simple proposal (19 March 2015)

Pumpkins, outliers and the Doing Business illusion (4 November 2014)

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Michael Martens, "Die verkehrte Welt der Weltbank" ("The upside down world of the World Bank") (26 January 2013)

What did not work

ESI report: Vladimir and Estragon in Skopje – A fictional conversation on trust and standards and a plea on how to break a vicious circle (17 July 2014)

Learning from enlargement

ESI report – The difference of leadership - Lessons from Croatia (April 2014)

The ESI enlargement project: www.esiweb.org/enlargement