Does EU enlargement policy change countries? Can it inspire the people who have to push through deep and complex reforms? Does it help ensure respect for fundamental rights?

What really are the minimum political standards that candidates will have to meet? What is, in the European Commission’s view, a “functioning market economy”?

What is the future of the Directorate General for Enlargement, the department of the European Commission in charge of this policy? And what is the future direction of the DG for Enlargement’s actions, given the unpopularity of the current policy in certain key member states?

Measuring alignment?

2013 EU assessments of countries according to the 32 chapters assessed. When it comes to the state of alignment, Turkey is ahead, despite many chapters being blocked. Macedonia is second, despite not being allowed to negotiate. Serbia is ahead of Montenegro. In October 2013 Albania was the very last. For the origins of the assessments in the 2013 reports see at the bottom of this text. The effects of producing such tables in a credible way is the subject of this text.

For the score this conversion used is: Advanced = 3 points, Moderate = 1 point, Early = 0 points (Source: EU progress reports – see below!). Since Bosnia and Kosovo have different types of progress reports they are not included here.

This week in Brussels I gave a presentation on the future of EU enlargement policy. The occasion was a strategy brainstorming session of the senior team of DG for Enlargement in Brussels, made up of some 60 people. The meeting followed similar presentations to policy makers in Berlin, Stockholm, Zagreb, Skopje, Brussels, Istanbul, Paris, and Rome. While I spoke in Brussels, my colleague Kristof presented similar ideas to Croatian Foreign Minister, Vesna Pusic, in Zagreb.

I was asked to be provocative. So I started with a personal encounter from a few weeks ago.

During a late night conversation in Zagreb, a journalist from a very respected European paper in a large EU member state told me that in his view “DG Enlargement should be shut down.” The argument, (which I had heard before in large EU member states I know well) was as follows:

None of the countries in the Balkans (or Turkey) are today even close to meeting what should be the EU’s demanding standards. They have weak institutions, corrupt administrations, create few or no jobs, and have incredibly polarised political environments. Nor are they moving in the right direction at a credible speed in overcoming these problems to make real change likely in the next decade or two. The EU has already admitted too many weak countries. Against this background having a DG for Enlargement creates constant pressure to repeat an earlier mistake. “Can you really imagine Albania in the EU any time soon?” And if you cannot, what then, is the point of a DG for Enlargement?

A few years ago such a view would have been very radical. In some European member state parliaments it is now on the way to becoming the new mainstream.

Of course, there will continue to be a DG dealing with enlargement for the foreseeable future. There is a policy, there are commitments, and there is inertia. The “European perspective” still produces real results. It is an “anchor.” It is leverage, at a low cost to the EU.

However the challenge posed by skeptics calls for a credible answer to the question of whether or not the basic premise of accession policy – that it changes countries for the better, and for good – is valid. And does the European Commission offer credible assessments of progress, or is it condemned by bureaucratic self-interest to be a cheerleader for badly prepared countries? (Or, to avoid this criticism, does it end up being seen as unfair in accession states?)

We accept that there is a crisis of credibility of the process. We are also convinced that there is an opportunity to substantially improve the impact of what is being done today by the EU in accession countries without changing the basic policy. The focus must return to the concrete and visible results in accession countries – “concrete” and “visible” for skeptics as well.

Enlargement policy needs to mobilise people or it fails. Without the mobilisation of policy makers, civil servants, civil society, and interest groups in accession countries, the kind of changes that have to happen will not happen.

It is here that we encounter a problem with the way many measure accession progress today: the language of “counting chapters opened.” Any complex process generates technical language, bureaucratic procedures, and jargon for those most involved. In the case of enlargement, however, the technical language has crowded out a focus on what makes this policy worthwhile and inspiring.

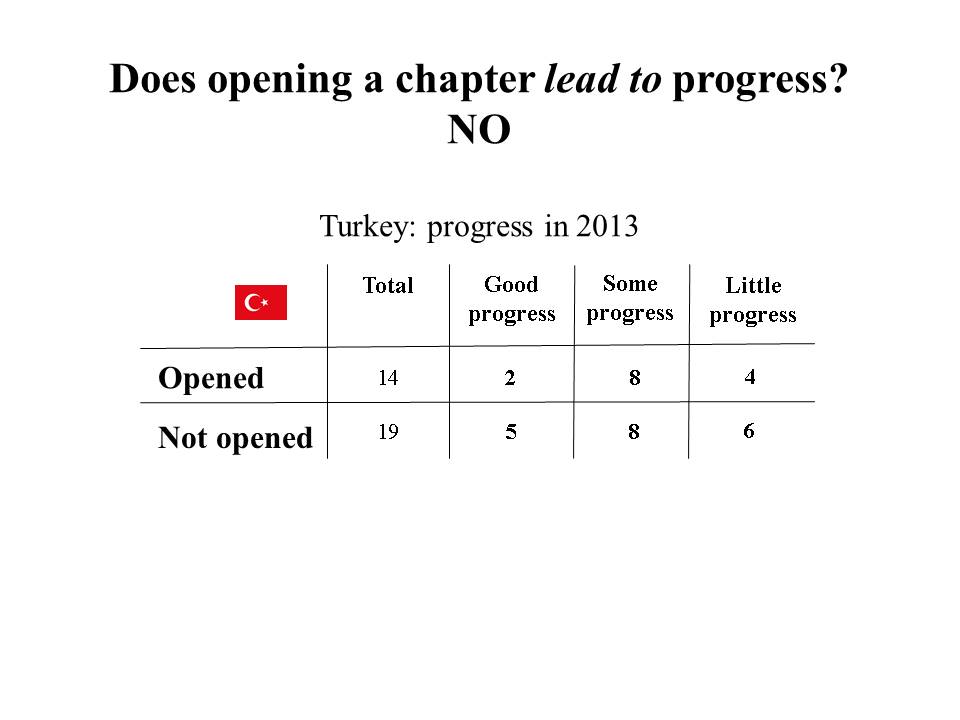

Recently I asked some of my Turkish friends what they thought the EU should do next in Turkey. Their answer: “Open Chapter 23. Then the EU can seriously discuss fundamental rights with Turkey.” This is how very serious and committed people talk, full of good intentions. And yet, it is puzzling. For when one asks “what do you believe happens after a ‘chapter is opened’ that makes any real progress more likely? Is there evidence that ‘chapter-opening’ produces change?” people pause. Rightly so, as I showed in my Brussels presentation. There is in fact no evidence that “chapter opening” produces change – Turkey shows this best in recent years – that progress in “un-opened” chapters is faster or slower than in “opened” ones. A country can make all the reforms and then “open and close” all chapters at the very end (Croatia did this in many key policy fields). It can open many chapters and make no progress for years.

See this table. Note that it is based on the Commission’s own assessments in the 2013 progress reports (For more on these assessments see the ESI scorecard further below):

The argument is not against the need to have “chapters,” which define separate policy areas, from consumer protection to public procurement or waste management. These are useful conventions to deal with the vast range of European standards and policies.

However, what really matters is that the EU spells out clearly, publicly, fairly, and strictly – and in a way that is understood by the broadest possible public in Albania, Turkey, Serbia or Macedonia – WHAT the basic and fundamental rights and standards should be in a country that wants to join. And it should do this regardless of whether a “chapter” is opened (or a member state decides to veto this, as has happened and may well continue to).

This is what accession is about from the very beginning. To allow for a “veto” against focusing on key issues makes no sense at all. What does make sense is a focus on closing “chapters,” which in any case only happens at the very end, and in turn depends on the nature of the reforms being done!

So by all means, open Chapter 23 with Turkey (and every country), if this is possible. And yes, it was good to “open a chapter on regional policy” (Chapter 22), last summer. It was a “signal” that there was still a process in motion. But in the end, it was also a strange response to the drama of the Gezi protests and their subsequent repression. Yes, there is a process, as the EU stated, but one that does not address WHY opening Chapter 22 is an answer to the question most observers were asking about the state of democracy. How did opening a chapter on regional policy change anything meaningful in Turkey in 2013? What has it changed since this was done?

The bureaucratic steps designed many years ago to make enlargement manageable are here to stay: the categories of potential candidates, opening one of 35 chapters, opening benchmarks, closing chapters. The bureaucratic process is not the problem. Nor is the fact that at every step, 28 member states have a veto. This is simply a fact of life.

However, what can and must happen is that the European Commission – and supporters of enlargement – see this ladder and the more than 70 steps for what it truly is: an instrument to many more worthwhile ends. And it is only those ends that matter to skeptical EU member states and to people in accession states: more vibrant public debates on political issues, particularly on television. Less discrimination of minorities, whether LGBT or religious minorities. More transparent spending whenever public agencies procure goods and services. A credible strategy to ensure safe food. Environmental inspectorates that ensure that dangerous waste is dealt with appropriately. Less polarised politics. A credible judiciary. Rules for businesses that allow fair competition. And many more…

Take another example. There is an esoteric debate, reminiscent of what scholars discussed in the cathedral schools of medieval Europe, on what is a “functioning market economy” for the European Commission. And in every progress report there is one section on “economic criteria.”

The EU insists that all accession candidates have a functioning market economy before they join: this makes intuitive sense. But the European Commission does not explain how it recognises one. Turkey has a “functioning market economy,” according to the EU. Serbia does not. One could have many long debates on whether a country that is not creditworthy has a functioning market economy (Greece? Cyprus?). Is this status linked to growth or its absence? (Was Finland a functioning market economy in 1988, stopped being one in 1993, and became one again in 1995?)

In fact, I recently learned that some people are trying to take the Commission to court (!) to disclose what its (secret) yardstick for measuring the functionality of an economy is. But it seems a misleading and irrelevant debate. If the Commission WOULD say that Albania will have a “functioning market economy” in 5 years, would members of the Bundestag or the Dutch public believe it? What does withholding this label do for Albania and the EU?

Would it not be better to assess countries by a few clear, measurable, and meaningful outcomes – the results of good economic policy? And to rewrite the currently unreadable and incomprehensible economic sections of progress reports so as to trigger regular and widespread public debates on economic fundamentals?

This could be done by defining and explaining a few key indicators for non-economist readers. Take the employment rate – how many people of working age have worked at least some in the past week, as measured by a credible standardised labor force survey? (Counting people employed in subsistence agriculture – how many of them are among the “employed?” This is also hugely interesting.) Then one looks a bit closer: if employment is low, is this because few young people work? Or few women?

An accession candidate should focus on these questions, and a progress report by the commission should highlight them, which it does not currently do. In the 2013 Macedonia progress report the authors gave TWO employment rates: 40.7 percent on page 16 and 48.2 percent on page 61, in the same report! (It obviously did not seem central to the authors).

A country that has a low employment rate and yet aims to convince the EU that its economy can, after accession, “withstand competitive pressures” should be asked to show – over the period of the accession process – that it can address this issue seriously, and with at least some success. This is a debate worth having and renewing every year.

The same could be said for other outcomes of economic policy: what about exports per capita, the stock and flow of FDI, the qualifications of the future work force (as measured by the OECD’s PISA tests, which amazingly, not all candidate countries are currently required to participate in), or the ability to spend EU grant money on development?

For most of these outcomes of economic policy there are robust indicators that allow comparisons over time and between countries. For some the European Commission can easily construct them. Indicators work best if they are completely plausible, and intuitively make sense to a broad public. And there need not be 20. The World Bank’s Doing Business reports started with five in 2004. Better five that every reader can understand, than twenty that are esoteric and hard to grasp.

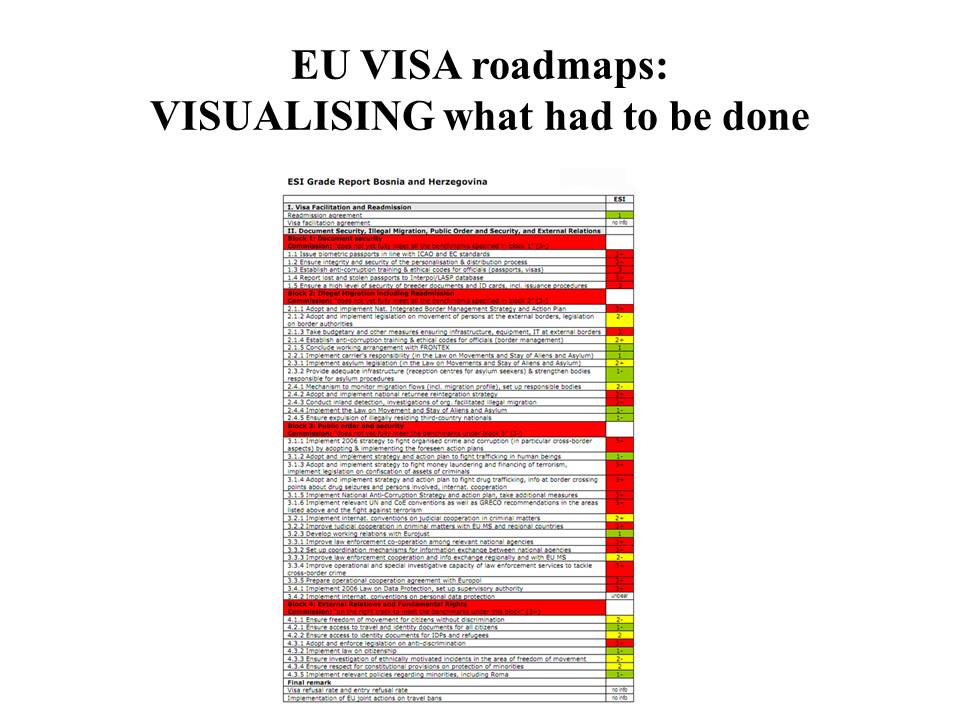

The same is true for policy areas covered in the chapters. In my Brussels presentation I suggested doing for each chapter – and for each country – what the EU has done in the recent visa liberalisation process: produce one document that clearly sums up what the core requirements are under each policy area (or chapter) that every accession candidate should meet. They could look like visa liberalisation roadmaps (see here examples)

“Core” requirements means that these roadmaps for chapters need not include everything, but rather most of the important criteria – requirements that countries only need to meet shortly before actual accession can be excluded. These requirements should focus on OUTCOMES: not just to pass a law, but also to “pass a law, have a credible institution and implement it.” And these requirements should be assessed annually in the progress reports for all countries, so they can be compared. There is no reason not to do this in all 7 countries, including Albania and Montenegro, Serbia and Kosovo. This would trigger very healthy debates and competition everywhere. In this way the annual progress report of the European Commission, its sections on “economic criteria” and on the policy areas in the 33 chapters, would become readable, interesting, and useful. It would address all four strategic objectives:

- Fairness: Regular fair public assessments of where accession countries really stand in terms of meeting EU criteria.

- Strictness: Strict public assessment of where accession countries are failing or even falling behind. The more concrete and specific the assessments are of what is missing, the better.

- Clarity: Any EU assessment needs to be understood, not just by a handful of experts, but by the broader interested public in accession countries and in the EU. (Sections that are incomprehensible to an interested non-expert should be cut and rewritten).

- Comparability: Any assessment should encourage two types of comparisons: between the situation in accession countries and EU standards, and among accession countries. Comparisons help both the fairness and the strictness of assessments. They encourage friendly competition and mutual learning from best practice.

ESI believes that the regular progress reports – published annually by the European Commission on every applicant country already now – are the obvious and best instrument to achieve all of these objectives. Improving them is rightly at the center of any debate on how to increase the impact and credibility of current enlargement policy.

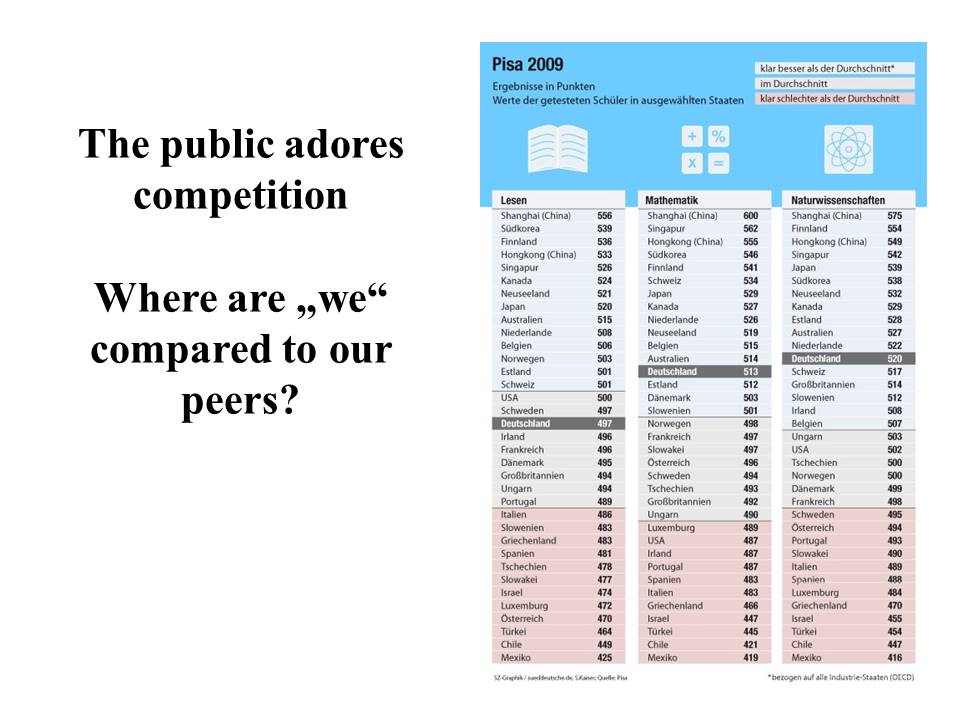

We are convinced that, building on what the Commission is already doing, progress reports could easily have the same impact on reform debates and reforms in accession countries as the regular OECD Pisa reports have had. Since 2000 these have reshaped the global debate on education.

This would help the Commission to keep (or regain) the trust in its assessments, which it needs to be effective.

In the end, the success of the commission in the field of enlargement cannot be measured by formal criteria: how many countries have started accession talks or how many chapters have been opened is not what matters most. What matters is closing chapters. And this can only happen after reforms are implemented. This means what matters now is what best helps the reform process.

BRUSSELS PRESENTATION

Below are a few slides from my Brussels presentation. In the next weeks we are planning to organise many more presentations across Europe. We integrate the feedback into the next presentations and policy papers. If you have thoughts on this, please do let us know: you can write directly to g.knaus@esiweb.org.

One reason PISA tests capture the public imagination: they make it possible to compare results between countries and over time. But the ranking is not a gimmick for the media: the results also allow detailed analysis, such as what kind of schools are doing better than others? Are there differences between reading and science results? Between girls and boys? How significant are the discrepancies between the best and the worst performing schools?

A notable strength of PISA is that it focused on results, not perceptions. DG enlargement needs the same. A credible yardstick – a gripping, readable annual report – would achieve all of these goals. The progress reports should be this:

This requires that all parts of the reports be read, understood, and taken seriously by at least the following members of a focus group: the civil servants who work on it, political leaders in government and opposition, business people who care about EU accession for what it means for them, critical journalists, civil society activists, and interested followers of the news, who might be tempted to look for a translation of the report.

See below a possible focus group in Macedonia: this IS the readership of these reports in any country.

At the same time EU member states need to see what is being done.

There are three parts to progress reports, where different ways of assessment are needed:

Political criteria: A focus on outcomes and areas where countries fall short. This is NOT likely to be usefully measured in quantitative terms, but best by reference to minimum standards, (which need not be low, but should be plausible). More on this in the next ESI reports.

Economic criteria: A focus on plausible OUTCOMES of good policy, a mere handful of key and obvious indicators.

Alignment with EU policies and regulations in sectors: The production – for the 33 chapters – of roadmaps would help because it would allow turning implementation into scorecards. This WAS done for visa liberalisation:

The key is how to identify core objectives in each policy field. The expertise for most or all of the policy fields currently exists in the Commission, as does the text.

This would then also allow comparisons. And this in turn would inspire debates, allow leaders to focus, and allow the media to analyse … it would put the results of the process – not the formal opening of closing of chapters – at the center of attention.

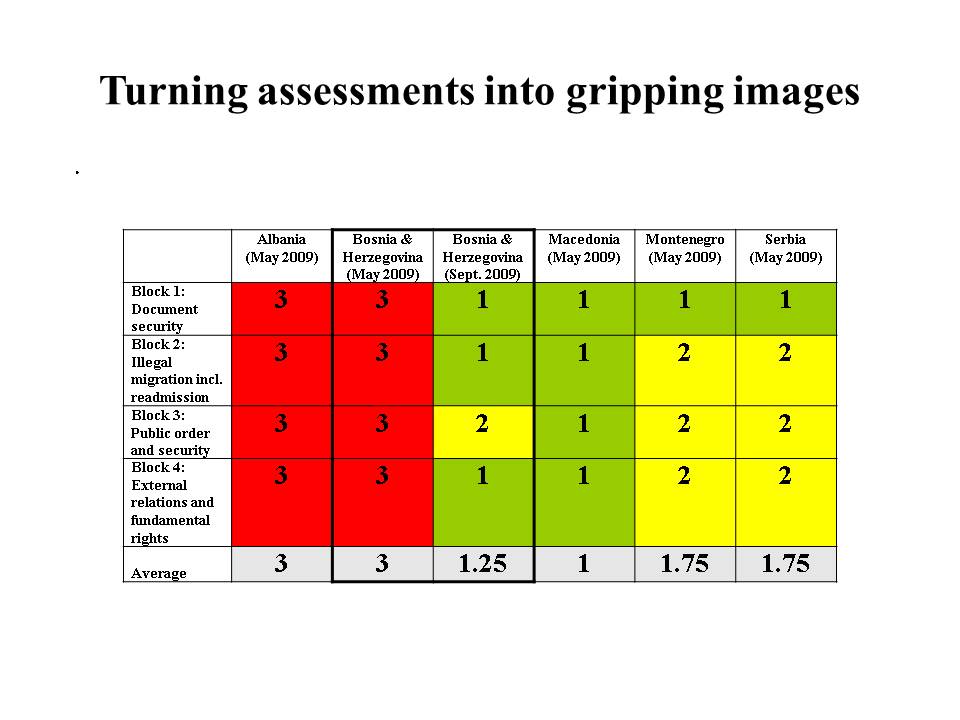

Rethinking the methods of assessment would also allow countries to make real efforts to try to beat low expectations… and to know that this would be recognised. It would allow certain ministers in a government to stand out. This is what happened to Bosnia during the visa liberalisation process in the summer of 2010. (See below the scorecard before and after this real effort).

At the same time, this would allow critical member states to understand in detail HOW the European Commission arrives at its assessments.

All this leads to a few concrete suggestions for EU accession future progress reports:

- Precise formulations (even more so than today, though in 2013 this was already done)

- In assessing “alignment” (or “preparation”) consider moving towards terms that more clearly indicate the required end-state: “Fully met,” “Largely met,” and “Not yet met.”

- Build each chapter assessment on publicly available individual chapter roadmaps, which also list the indicators used to assess implementation.

- Add scorecards for each chapter

- Report on all seven countries in the same way so they can be compared.

- Consider adjusting chapter roadmaps every three years in light of the changing EU acquis.

Scorecard legend for the table below:

Green: alignment is/preparations are advanced / well advanced / rather advanced / relatively advanced; high / sufficient level of alignment)

Yellow: alignment is/ preparations are advancing / moderately advanced / on track

Red: alignment is/ preparations are starting / at an early stage / not very advanced / not yet sufficient. / A country has started to address its priorities in this area.

Alignment with the acquis – per chapter – 2013 Progress Reports

|

Chapter |

Turkey |

Mace-donia |

Serbia |

Monte-negro |

Albania |

|

1: Free movement of goods |

3 |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

2: FoM for workers |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

3: Right of establishment, freedom to provide services |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

4: Free movement of capital |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

5: Public procurement |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

6: Company law |

3 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

7: Intellectual property law |

3 |

1 |

3 |

3 |

0 |

|

8: Competition policy |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

9: Financial services |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

10: Information society & media |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

11: Agriculture & rural development |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

12: Food safety |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

13: Fisheries |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

14: Transport policy |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

|

15: Energy |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

16: Taxation |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

17: Economic & monetary policy |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

18: Statistics |

3 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

19: Social policy & employment |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

20: Enterprise & industrial policy |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

21: Trans-European networks |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

22: Regional policy, structural instr. |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

23: Judiciary & fundamental rights |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24: Justice, freedom & security |

0 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

25: Science & research |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

26: Education & culture |

1 |

1 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

|

27: Environment & climate change |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

28: Consumer & health protection |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

29: Customs union |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

30: External relations |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

31:Foreign, security, defence policy |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

32: Financial control |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

33: Financial & budgetary prov. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Detailed assessment by the European Commission (2013)

|

Chapter |

Turkey |

Macedonia |

Serbia |

Montenegro |

Albania |

|

1: Free movement of goods |

The state of alignment in this chapter is advanced. |

Preparations in the area of free movement of goods are advanced. |

Preparations in the area of free movement of goods are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of free movement of goods are relatively advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

2: Freedom of movement for workers |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are still at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Alignment with the acquis is still at an early stage. |

Preparations in the area of freedom of movement for workers are at an early stage. |

|

3: Right of establishment and freedom to provide services |

Alignment is at an early stage. |

In the area of postal services, the level of alignment is advanced. There is not yet full alignment with the acquis, particularly as regards mutual recognition of professional qualifications, free movement of services and establishment. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

Substantial efforts are still needed to align the legislation and implement the acquis on mutual recognition of professional qualifications. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

4: Free movement of capital |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations are on track and gradual harmonisation of the regulatory framework for payment systems is under way. |

Alignment in this area is moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

5: Public procurement |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of public procurement are advanced. |

Alignment in the area of public procurement is moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of public procurement are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the field of public procurement are moderately advanced. |

|

6: Company law |

Turkey is well advanced in this area. |

Preparations in the area of company law as a whole are moderately advanced. |

Alignment in the area of corporate law is well advanced. |

Preparations remain moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

7: Intellectual property law |

Alignment with the acquis is advanced. |

Preparations in the field of IPR are moderately advanced. |

Alignment in the area of IPL is advanced. |

Preparations are advanced. |

Preparations are not very advanced. |

|

8: Competition policy |

Turkey is moderately advanced in this area. |

Preparations in this area are advanced. |

Alignment in this area is moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

Preparations for the revision of state aid legislation are at an early stage. |

|

9: Financial services |

Preparations in the area of financial services are advanced. |

Alignment with key parts of the acquis on financial market infrastructure has not yet been achieved. In the area of financial services, alignment with the acquis is moderately advanced. |

Alignment in the area of financial services is moderately advanced. |

The level of alignment is moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

10: Information society and media |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are on track. |

Alignment with the acquis in this area remains moderately advanced. |

Preparations are on track. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

11: Agriculture and rural development |

Preparations in the area of agriculture and rural development are at an early stage. |

Preparations remain moderately advanced. |

Alignment with the acquis remains at an early stage. |

Alignment with the acquis is at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are not very advanced. |

|

12: Food safety, veterinary and phytosanitary policy |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations in the area of food safety and veterinary policy are well on track. Preparations in the phytosanitary area are at an early stage. |

Preparations in the area of food safety, veterinary and phytosanitary policy are moderately advanced. |

Preparations remain at an early stage. |

Preparations remain at an early stage. |

|

13: Fisheries |

Alignment in this area is at an early stage. |

A large proportion of the fisheries acquis is not relevant as the country is landlocked. |

Preparations in the area of fisheries are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations are not very advanced. |

|

14: Transport policy |

In the area of transport, Turkey is moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Serbia is moderately advanced in its alignment with the acquis in this area. |

Preparations in this area are advanced. |

Preparations in the area of transport are not very advanced. |

|

15: Energy |

Turkey is at a rather advanced level of alignment in the field of energy. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of energy are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of energy are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are not very advanced. |

|

16: Taxation |

Preparations in this chapter are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of taxation are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of taxation are moderately advanced. |

Montenegro’s alignment with the acquis is moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

17: Economic and monetary policy |

Turkey’s level of preparedness is advanced. |

Preparations in this area are advanced. |

Serbia is moderately advanced. |

Alignment in the area of economic and monetary policy is moderately advanced. |

Preparations are not yet sufficient. |

|

18: Statistics |

Alignment with the acquis is at an advanced level. |

Preparations in the field of statistics are advanced. |

Serbia is advanced in the area of statistics. |

Preparations in the area of statistics are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

19: Social policy and employment |

Legal alignment is moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Serbia has started to address its priorities in this area. |

Montenegro has started to address its priorities in this area. |

Preparations in the area of social policy and employment are not very advanced. |

|

20: Enterprise and industrial policy |

Turkey has a sufficient level of alignment in this chapter. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are on track. |

A strategic effort to promote skills at all levels in sectors where Montenegro has significant trade with the EU will be important to improve competitiveness and ensure preparedness for competitive pressures and market forces within the Union. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

21: Trans-European networks |

Alignment in this chapter is advanced. |

Preparations in this area are advanced. |

Preparations in the area of trans-European networks are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of trans-European networks are not very advanced. |

|

22: Regional policy and coordination of structural instruments |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are not very advanced. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

|

23: Judiciary and fundamental rights |

|

|

|

|

|

|

24: Justice, freedom and security |

Alignment in the area of justice and home affairs is at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are advanced. |

Serbia is moderately advanced in the area of justice, freedom and security. |

Alignment with the acquis in the field of legal migration, asylum and visas is still at an early stage. |

Preparations in this field are advancing. |

|

25: Science and research |

Turkey is well prepared in this area. |

Preparations in this area are on track. |

Preparations in the area of science and research are on track. |

Preparations in this area are well on track. |

Preparations are not sufficiently advanced. |

|

26: Education and culture |

(No assessment of the state of alignment.) |

Preparations in the areas of education and culture are moderately advanced. |

Preparations for aligning with EU standards are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

27: Environment and climate change |

Preparations in these fields are at an early stage. |

Preparations in the field of the environment are moderately advanced while preparations in the field of climate change remain at an early stage. |

Priorities in the fields of environment and climate change have started to be addressed. |

Preparations in these areas are still at an early stage. |

Preparations in the fields of the environment and climate change are at an early stage. |

|

28: Consumer and health protection |

Preparations in this area are on track. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area remain moderately advanced. |

Preparations in these areas are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are starting. |

|

29: Customs union |

The level of alignment in this area remains high. |

Preparations in this area are advanced. |

Preparations in the area of the customs union are well on track. |

Preparations in the field of customs union are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

30: External relations |

There is a high level of alignment in this area. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of external relations are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in the area of external relations are on track. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

31: Foreign, security and defence policy |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are well advanced. |

Preparations in the area of foreign, security and defence policy are well on track. |

Preparations in the area of foreign, security and defence policy are on track. |

Preparations in this field remain on track. |

|

32: Financial control |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations in this area are moderately advanced. |

Preparations are moderately advanced. |

|

33: Financial and budgetary provisions |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations are at an early stage. |

Preparations in this field are at an early stage. |

Preparations in this area are at an early stage. |

Preparations in the area of financial and budgetary provisions are at an early stage. |