Essay 2 - The popularity of pushbacks – lessons from Australia

- The Asian protection-desert

- How refoulement became popular

- Impotent opposition

- Morality and politics

- Is the Australian example killing the Refugee Convention?

- ESI online presentation and debate

Dear friends of ESI,

It is nine weeks until 28 July, the 70th anniversary of the Geneva Refugee Convention.

This Convention sets out the criteria to determine who is a refugee. States pledge to ensure the protection of anyone who reaches their territory and meets these criteria. They commit not to push potential refugees back into danger, which had been the fate of tens of thousands of European Jews trying to escape persecution in the period before the Refugee Convention was adopted.

For more: Swiss tragedy – borders and refoulement

It is often said that the non-refoulement (no-pushback) principle is the corner stone of the global refugee protection system. But there are two problems: first, the global refugee protection system is not global. Second, even in Europe, where the refugee convention has been ratified by most states, respect for the non-refoulement principle is not secure. The case of Australia shows just how quickly a social consensus in favour of pushbacks can emerge even in countries which ratified the convention a long time ago.

The Asian protection-desert

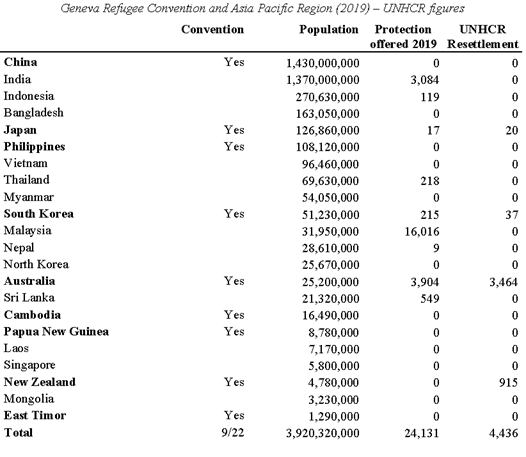

East and Southeast Asia is a protection desert. Here, 22 states are home to almost 4 billion people. This is half the global population. The economic weight and global influence of this region is set to grow even further in the coming decades. For the Geneva Refugee Convention, however, the rise of Asia is hardly reassuring.

In this region few countries have ratified the convention. Of those that have, most do not apply it, neither offering protection (China) nor resettling refugees chosen by UNHCR. Malaysia, India and Sri Lanka allow UNHCR to carry out refugee status determination on their territory. However, they expect identified refugees to be resettled elsewhere. As few Asian countries take part in resettlement, this means the refugees must typically be moved to other continents.

If one includes the decisions made by UNHCR, international protection was offered to 24,000 people in 2019 in the whole region. Canada alone offered as much protection that year. (For total numbers of refugees hosted in this region and elsewhere see here)

For decades, Australia has been an oasis of protection in this region. Even today any refugee leaving Iran and heading east, crossing Pakistan, India, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia, would need to reach Australia to get to a country that has ratified the refugee convention. Australia was among the first countries in the world to do so. In 1978 it was among the first countries in the region to create a national asylum body. It became one of the leading destinations in the world for the resettlement of Vietnamese boat people. It continues to be the only country in this region that accepts a few thousand refugees every year through resettlement.

At the same time, Australia practices an aggressive policy of refoulement. A government video from 2014 sums up its policy:

“The message is simple: if you come to Australia illegally by boat, you will never have a way to become an Australian citizen. The rules apply to everyone: families, children – there are no exceptions.”

Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders website

Since mid-2013, Conservative and Labor governments have sent the same message to Hazara from Afghanistan fleeing the Taliban, to Christian converts from Iran fleeing the Islamic Republic and to refugees from Sudan fleeing indiscriminate violence in Darfur: if you try to come without a visa across the sea you will never get protection here. This policy remains in force today under the name “Operation Sovereign Borders.” It means that the Australian navy will turn around” any boat with asylum seekers it encounters and send it back to Indonesia or Sri Lanka. Alternatively, it might transfer asylum seekers to detention centres on the Pacific islands of Manus, in Papua New-Guinea, or the microstate Nauru, thousands of miles from Australia, for so-called “offshore” processing of any asylum claims.

More:

NEW The Damned of Papua New Guinea

How refoulement became popular

Four things are striking about this policy: its effectiveness, brutality, popularity and the impotence of its most eloquent critics. Let us look at each in turn.

Effectiveness

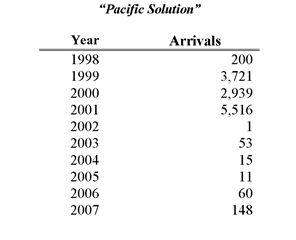

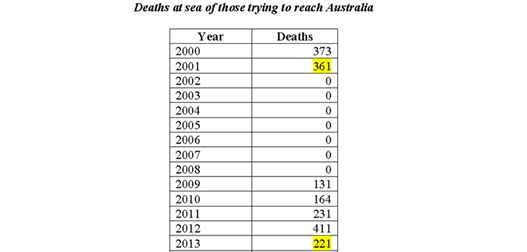

Not once, but twice since 2000 a combination of pushbacks and offshore processing has reduced the numbers of irregular arrivals to zero. This happened after prime minister John Howard introduced this policy in August 2001: the number of people arriving irregularly in boats fell from more than 12,000 in three years to less than 300 in six years. Howard called this the Pacific Solution.

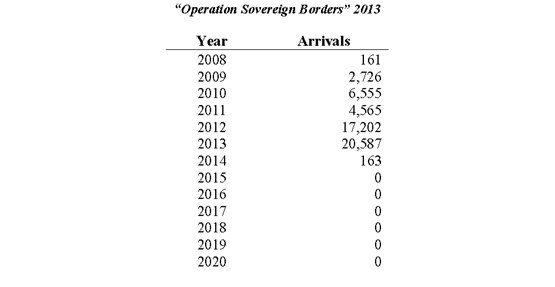

The decline in arrivals was even stronger after another prime minister, Tony Abbott, launched Operation Sovereign Borders in September 2013: the number of people arriving irregularly in boats fell from 52,000 in five years to zero from 2014 onwards.

Brutality

Robert Manne, a leading Australian public intellectual and a descendent of European victims of the Holocaust, called this an “almost uniquely cruel asylum seeker policy” in 2018. According to Manne, its goal was to strip people “bare of dignity and of hope” to be “remorselessly and systematically destroyed. The destruction of these people in both body and spirit is no secret.” When the Australian prime minister explained his country’s border policy to the US president in a telephone conversation in 2017, Donald Trump was impressed: “You are worse than I am.”

Greg Lake of the Australian Immigration Department was responsible for managing the camps on Nauru and Manus in 2012. He later explained that the intention behind the measures had been clear to everyone: to deprive the people on the islands of any hope for the future. Therefore, they were given a number and never addressed by their name. Their daily lives were organised down to the last detail so that they had no control over their lives, and parents none over that of their children. They were told right at the beginning that they would be stuck for many years.

John Zammit, an Australian psychologist who worked on Manus Island in 2013, later described the camp as “hellish” and the psychological care he was supposed to provide there as pointless. Zammit saw “people falling apart” in front of him, worn down by a life like a nightmare: humiliating days behind fences, senseless rules, inmates who had to beg even for toilet paper and soap. Many fell into apathy after years of imprisonment and uncertainty, queuing every night for sleeping pills and antidepressants. Others injured themselves. One refugee was beaten to death by security staff during riots, a second died due to delayed treatment. From 2013 to 2018, 14 inmates committed suicide on Manus and Nauru.

John Zammit described the conditions in the camps as torture. In February 2020 the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in The Hague wrote to an Australian MP that “some of the conduct at the processing centres on Nauru and on Manus Island appears to constitute the underlying act of imprisonment or other severe deprivations of physical liberty” under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court:

“The duration and conditions of detention caused migrants and asylum seekers – including children – measurably severe mental suffering … These conditions of detention appear to have constituted cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment and the gravity of the alleged conduct thus appears to have been such that it was in violation of fundamental rules of international law.”

Abdul Aziz Muhamat, held in Manus camp for six years. (@Michael Green)

One way to grasp the reality of Manus is to listen to a series of conversation, initially carried out in secret via text messages sent between Abdul Aziz Muhamat, a Darfuri refugee who was held in Manus for six years, and an Australian journalist:

The Messenger from Manus – The Conversation

The human cost of this policy has also been described in many reports, leaked files, and documentaries:

UNHCR on Manus and Nauru, 2016

Guardian: the Nauru Files, 2016

Human Rights Watch on

Australia/PNG: Refugees Face Unchecked Violence, 2017

Chasing Asylum, the film

Indefinite Despair: The Tragic Mental Health Consequences of

Offshore Processing on Nauru, MSF, 2018

Popular pushbacks

In 2019, Abdul Aziz Muhamat was awarded a prestigious human rights prize in Geneva. In 2019 another Manus detainee, the Iranian Kurdish writer Behrouz Boochani, won a prestigious literary prize for a novel based on this experience. And yet, even as the Australian public learned more about the effects of this policy on men, women and children they could see and hear, the majorities’ support for Operation Sovereign Borders remained intact.

Are Australians a people without empathy? Are its politicians particularly cruel? The short answers are no and no. The longer answers are more complicated.

Australia is a society of immigrants. Its population rose from 7 million in 1945 to 25 million today. It remains today among the countries which are most supportive of immigration in the world, second only to Canada. A 2019 report by the Scanlon Foundation noted that 64 percent agreed with the statement “Immigrants today make our country stronger because of their work and talents.” This is close to Sweden and far above Italy (12), Greece (10) and Hungary (5 percent). 67 percent of Australians support diverse immigration. 70 percent reject discrimination based on race or religion for immigrants. 85 percent agree that “multiculturalism has been good for Australia.”

Until 1970, Australia pursued what was then called a “White Australia” immigration policy. However, these days of official racism are gone. Starting in the 1970s, Australia resettled almost 160,000 Vietnamese refugees. Surveys show that “support for discrimination on the model of the historic White Australia Policy fails to gain support from more than 30 percent of respondents.”

Racism does not explain majority support for Operation Sovereign Borders. Nor does any ingrained hostility to refugees. Most Australians believe in refugee protection and resettlement. 80 percent agreed in 2016 that “refugees who have been assessed overseas and found to be victims of persecution and in need of help” should be brought to Australia. 58 percent supported the government’s plan to bring an additional 12,000 refugees from the Syrian conflict to Australia in 2015, with 34 percent opposed. Half of Australians are also concerned about harsh treatment of asylum seekers. Asked: “Are you personally concerned that Australia is too harsh in its treatment of asylum seekers and refugees?” 48 percent stated in 2019 that they were “a great deal” or “somewhat” concerned.

What about Australian politicians? In 2001, after embracing pushback policies and opening the Nauru processing centre, prime minister John Howard stated:

“We are a generous openhearted people taking more refugees on a per capita basis than any nation except Canada, we have a proud record of welcoming people from 140 different nations. But we will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come … we will decide and nobody else who comes to this country.”

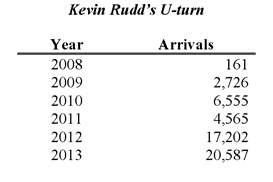

After promising and delivering control in August 2001, Howard’s party rose in the polls and he won re-election. However, in 2007 Kevin Rudd, the leader of the Labor Party, did the opposite. Rudd referred to the Good Samaritan as an inspiration and promised to end the policies of the Pacific Solution while running for office. He also won the election.

Rudd became prime minister in November 2007. In February 2008, his minister for immigration announced the end of the Howard policy, calling it a “cynical, costly and ultimately unsuccessful exercise.” The centres on Manus and Nauru were closed.

This was a turning point. Alas, Labor had not developed any plan beyond opposing Howard’s policy. The idea was to process all irregular boat arrivals on Christmas Island, which had the capacity to house 400 people. However, the number of people arriving by boat across the Indian Ocean increased from 161 (2008) to 2,726 (2009) to 6,555 (2010). Boat refugees were again the dominant topic in Australian politics.

Another human cost also became visible: the large number of people who drowned trying to reach Australia. A terrible accident took place in December 2010 off Christmas Island, which was captured on television. Another accident led Australian essayist Robert Manne to write in 2011:

“On the weekend perhaps two hundred asylum seekers bound for Australia perished off the coast of Java. One key question about Australia’s asylum seeker problem was finally resolved. No one can any longer pretend that a regime of spontaneous asylum seeker boat arrivals and onshore processing does not carry with it grave and arguably unacceptable risks.”

The Labor government tried to regain control. In summer 2012, it reopened Manus and Nauru but only a small proportion of those arriving now were sent there. And boats kept arriving in ever greater numbers.

Then, prime minister Rudd went further. On 19 July 2013 Kevin Rudd declared:

“As of today asylum seekers who come here by boat without a visa will never be settled in Australia. Under the new arrangement signed with Papua New Guinea today – the Regional Settlement Arrangement – unauthorised arrivals will be sent to Papua New Guinea for assessment and if found to be a refugee will be settled there … Our country has had enough of people smugglers exploiting asylum seekers and seeing them drown on the high seas …There is no cap on the number of people who can be transferred to Papua New Guinea.”

2013 was the year with most irregular arrivals in Australian history: 20,587. With elections approaching in September, opposition leader Tony Abbott campaigned for “a military-led response to combat people smuggling and to protect our borders”. He called it Operation Sovereign Borders.” On 16 August 2013, Abbott declared: “This is our country, and we determine who comes here … I will regard myself as having succeeded very well if we can get back to a situation of having three boats a year. Obviously, our ideal is to have zero boats.”

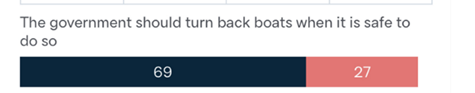

Labor lost the elections. Within two weeks of his election victory Abbot launched Operation Sovereign Borders. By the end of the year, thirty-one boats, carrying more than 770 people, had been forcibly turned back. The Australian government had brought about 1,600 people to the islands of Nauru and Manus between 2001 and 2007. Some 3,100 people were taken there between summer 2013 and today. From 2014 boats stopped arriving in Australia. A 2016 survey found that 69 percent agreed that the “government should turn back boats when it is safe to do so.”

Impotent opposition

Operation Sovereign Borders was criticized from the moment it was launched. And yet, advocacy efforts to get Australian leaders to end this policy had no impact. It is important to try to understand which arguments failed to convince and why.

One argument often made concerns the costs of this policy. This cost was enormous, estimated by the Australian Refugee Council at some 6 billion Euros since 2013. Recently a report by another group of NGOs noted that the cost of offshore processing to Australia was today more than 365,000 Euros per person per year. In 2017, the Australian government also reached a settlement with Manus detainees to pay them more than 47 Million Euros “rather than proceed with a six-month trial that would have involved evidence before the court from detainees of murder inside the detention centre, systemic sexual and physical abuse, and inadequate medical treatment leading to injury and death.” These are huge sums, yet their exposure did not erode public support. Cost arguments could not move those who were in favour of strong borders.

A second argument of critics concerned the legality of Australia’s policy: the claim that Australia violated its international obligations. Alas, there is no international court to which anyone might turn to establish a state’s violation of the refugee convention. Meanwhile, the Australian High Court consistently backed all aspects of this policy in numerous judgements.

A third argument is about Australia’s international reputation. This had been a strong argument in the 1970s for Australian policy makers during the Vietnamese boat people crisis. And yet, as we have seen, today Australia remains a leader in its region offering support to refugees. Meanwhile pushbacks have been carried out by governments throughout Southeast Asia for decades. Nor is public shaming by other Western democracies likely. The US openly embraced, and the US Supreme Court supported, pushbacks of boatpeople fleeing the brutal dictatorship in Haiti by its navy and coast guard long before Australia did. One of the first reactions to John Howard’s island policy came from the United Kingdom under prime minister Tony Blair, Denmark and the Netherlands, suggesting a debate on whether a similar border and asylum policy might not be needed in Europe, too.

Today it is obvious that many countries in the world, including in Europe, would rather emulate than criticize Australia. In August 2018, Matteo Salvini, then Italian interior minister, declared that Italy should imitate Australia’s “No Way” border control policy to stop everyone trying to cross the Mediterranean from North Africa:

“‘You know that in Australia there is the principle of “no way” – none of those who are rescued at sea set foot on Australian soil,’ Salvini said. ‘This will have to be achieved [in Italy]. My goal is not redistribution [of refugees] in Europe, but in the countries of departure… Bangladesh, Eritrea, Sudan, Ivory Coast, Tunisia, Pakistan, Mali.’ Genuine refugees fleeing war should be screened overseas and come to Europe ‘not in rubber dinghies but in aeroplanes’, Salvini said.” (24 August 2018)

Focusing on irregular arrivals, Matteo Salvini took his party, the Lega, from 6 percent in elections in 2014 to 34 percent in 2019. His Lega remains the most popular party in Italy today. And he is not the only European leader looking to Canberra’s deterrence policies for inspiration. So did Viktor Orban from Hungary, who won re-election on an anti-migration platform in 2018; Sebastian Kurz from Austria, who took over his party embracing Australian border policies; prime minister Mette Frederiksen from Denmark, who earlier this year stated that she wanted to reduce asylum applications in Denmark to zero:

“That’s what our target is. Of course, we can’t promise it. We can’t promise zero asylum seekers, but we can create a vision, like we did before the election, that we want a new asylum system and then do what we can to implement it.”

The Boris Johnson government in the United Kingdom has discussed imitating Australia for many months now. In March 2021 Johnson explained that sending asylum seekers abroad for processing was a humane policy that would save lives:

“The objective here is to save life and avert human misery because people are crossing the Channel who are being fooled, who are being conned, by gangsters, into paying huge sums of money, risking their lives. That’s why the home secretary has set out the tough series of proposals that you have seen. The objective is a humanitarian one and a humane one.” (19 March, Sunday Times)

In this context only a minority of Australian voters worry about Operation Sovereign Borders impacting on their country’s reputation. In a recent Lowy Institute Poll Australians answered that their country’s strict border policy helped (30 percent) or made no difference (40 percent) to its international reputation. Only 28 percent felt that it hurt.

Morality and politics

The strongest argument against this deterrence is neither money, nor legal obligations, nor international reputation: it is morality and compassion, and the reality of a rich democracy making innocent people seeking shelter suffer in order to send a message to others.

Making a moral argument, however, poses another dilemma to opponents of Australia’s harsh policy. It requires explaining how an alternative policy would not lead to a repetition of what happened between 2008 and 2013: more people setting out and many more dying at sea.

Australian leaders of both parties have kept coming back to this point. When more than 1,200 people drowned off the Libyan coast in one week in April 2015, Australian prime minister Tony Abbot told Europeans: “The only way you can stop the deaths is, in fact, to stop the boats. That’s why it is so urgent that the countries of Europe adopt strong policies that will end the people smuggling trade across the Mediterranean.” In October 2015, Abbott returned to this message in a speech in London:

“It’s now 18 months since a single illegal boat has made it to Australia … and – best of all – there are no more deaths at sea. That's why stopping the boats and restoring border security is the only truly compassionate thing to do.”

Liberal party leaders have won elections through tough positions on borders. Even if they were not convinced of this policy, they have seen it work for them. Labor party leaders have seen that not taking a tough policy on borders has brought electoral defeat. The political reality is that the current policy is popular with Australian voters, as many surveys have shown. Since 2013, it has been backed in parliament by both the government coalition (led by the Liberal Party) and the main opposition Labor Party. Between them these two currently hold 144 of 151 seats in the Australian House of Representatives.

In April 2016, Labor leader Bill Shorten warned that “there isn’t a single person in Labor who wants to see the boats start again.” In November 2017 Shorten repeated: “The processing facilities on Manus and Nauru were set up as transit centres to ensure Australia was not a destination for people smugglers, and to stop the deaths at sea. This strategy worked.” At the Labor party conference in 2018 a representative of the NGO Doctors Without Borders was invited to speak about the suffering caused to people held in Manus and Nauru. However, the party still decided to continue to back pushbacks and offshore processing, determined, as one spokesperson put it, “that we don’t adopt any policy that would start the drownings again.”

In 2019 Anthony Albanese was elected party leader, following Labor’s 2019 election defeat. Albanese had, in the past, expressed opposition to pushbacks. But by 2018 he was defending the policy of rejecting all boat arrivals. In a television interview he conceded: “the government’s policies have stopped the boats … They’re not coming, so the circumstances of rejecting boat arrivals has been achieved.” He said that the previous Labor government was wrong to believe that Australia’s border policies were not a “pull factor” for asylum seekers and that, if it won the forthcoming elections, Labor would be “tough on people smugglers” without being “weak on humanity.”

Is the Australian example killing the Refugee Convention?

It is important to acknowledge that there is a genuine moral dilemma for policy makers concerning irregular arrivals in flimsy boats across the sea.

Imagine you were the captain of an (Australian) warship that paced up and down the sea off a coast. You know that tens of thousands of men, women and children on this coast are preparing to set sail in unstable boats in order to travel to the land on the other side of the sea, which is many days away, and to apply for asylum there. You also know that 1,200 people drowned in such trips the year before.

Now your government has given you the task of stopping the next ten ships with a total of 3,000 people, picking them up and then placing them without exception on a small island in the middle of the sea. Life on this island is tough, people are locked up and cannot leave the island for many years. Some will try to kill themselves out of desperation. On the other hand, you know that if you get people there, tens of thousands of others will not get on board in the next few years. Nobody will drown anymore. In three years, that would be 3,600 people who did not fall victim to the sea, including hundreds of children.

You are a soldier obeying your government’s instructions, but what do you think of that? Is this a difficult, but nevertheless reasonable, even morally necessary task? Or are the policies which you are implementing deeply immoral, and you wake up feeling guilty at night thinking of those you abandoned on the island? In Australia, which has implemented such a policy with great popular support for the past 20 years, the answer from the government and most of its officials has been that such a policy is sensible and morally correct.

While the disastrous human consequences of the island policy are the result of conscious choices that involve moral responsibility, the deadly consequences of allowing boat journeys to resume are no less foreseeable.

And yet, it is also clear: if every potential refugee is pushed back around the world – from Australia to Italy, from Malaysia to Greece – there will be no global protection regime left. The burning question is whether there is a politically viable way forward of (less than total) control without brutality, not in some imaginary universe but as a practical answer to the challenges in the Indian Ocean, the Pacific or the Mediterranean.

Few publications have been more critical than The Guardian of Australia’s policy. An 2017 article describes this policy as a “brutal and obscene piece of self-delusion.” And yet, it concludes:

“An alternative to Australia’s current regime would be that people seeking safety by dangerous boat journey were intercepted – even rescued – and taken to a place of safety. These people can be processed and resettled to third countries where possible. This new regime would need commitments of money, of expertise, and political capital. It would, like any system, be imperfect and a small minority would seek to exploit it. But the guiding principle must be: do Australia’s actions increase the amount of protection in the world for those who need it? Australia’s current arrangement categorically fails this fundamental question. Stopping boats at sea does not necessarily mandate that those stopped must then be punished, month after month, year after year, in indefinite and arbitrary detention. The two are not linked.”

This hints at the most important lesson from Australia’s experience: to win over majority support for a policy preserving human dignity and refugee protection requires an alternative policy to maintain control, stop boats and prevent deaths at sea. A humane policy should prevent tens of thousands of people getting in boats, as in 2012-2013 in the Indian Ocean. It should achieve this without brutality, pushing people to suicides on distant islands and indefinite, inhumane detention. Is such a policy possible, in Australia and elsewhere? How can majorities be persuaded that it is?

There is a possibility that unless good answers are found to these questions the current consensus in Australia – that only pushbacks and the harshest deterrence reduce irregular migration, which is both morally and politically desirable – will be embraced elsewhere, in Asia and in Europe. If this happens refoulement will be normalised around the world.

This would be a fatal dagger driven into the heart of the Refugee Convention. So what is to be done?

Next week: How Italians responded to human tragedies at sea. The morality of sea rescues in the Central Mediterranean. The immorality of cooperation with Libya. And the politics of compassion in Rome and Brussels.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

It is the writer Robert Manne who has best captured the political gridlock on the issue of irregular arrivals to Australia, and the dilemma this has created for those who want to challenge the mindset in Australia’s capital Canberra. It is a dilemma relevant to refugee rights advocates everywhere.

“According to the ‘Canberra’ mindset … if the policies of offshore processing and naval turnback were once again abandoned, or even if the refugees on Nauru and Manus Island were brought to Australia, a signal would reach the people smugglers and an armada of asylum seeker boats would set sail.

By now ‘Canberra’ had even somehow managed to claim the moral high ground. The passage from Indonesia to Christmas Island or Ashmore Reef was perilous. On that passage more than 1,000 asylum seekers had drowned. Stopping the boats had therefore saved countless lives …

For many years, the argument between ‘Canberra’ and ‘the opposition’ has been gridlocked. The reason is that the principal claims of both ‘Canberra’ and ‘the opposition’ are true. It is true, as ‘Canberra’ claims, that the harsh deterrent policies … did succeed in stopping the boats. And it is true, as ‘the opposition’ claims, that the slow destruction of 2000 innocent human beings who had the misfortune of arriving on Australian shores not before but after 19 July 2013 is evil …

In general, the claims made by the ‘the opposition’ are moral and legal. They overlook a third dimension – the political. From the political point of view certain things are stubbornly self-evident … And it is clear that neither a Coalition nor Labor government will return to the policy position the Rudd government took in mid-2008 – the abandonment of offshore processing and naval interception and turnback – for the simple reason, as ‘Canberra’ understands … that these policies were responsible for the arrival by boat of 50,000 asylum seekers in the space of four years and for approximately one thousand deaths by drowning at sea.

By ignoring the political dimension, the stale truism that politics is the art of the possible, ‘the opposition’ has failed even to search for a politically feasible solution to the tragedy of the people who have been marooned on Nauru and Manus Island for the past five years or more. On the question of greatest importance and urgency – how might an Australian government be convinced to bring the refugees and asylum seekers on Nauru and Manus Island to Australia? – ‘the opposition’, as I have discovered in public argument, has nothing to say.”

It is a lesson in necessary humility, whose significance goes beyond Australia: to persuade leaders backed by democratic majorities to change a popular policy one needs to take seriously their concerns, and offer credible answers how a better, more moral policy might address them. This is as true in Australia as in Germany, France, Greece, Italy and the United States.

Part One

The promise and the agony – saving the refugee convention

Why International protection is at risk

Myths and facts on global asylum

Swiss tragedy – borders and refoulement

(From book: Which Borders do we need?)

Part Two

The popularity of pushbacks – lessons from Australia

The Damned of Papua New Guinea

Monday 14 June at 3pm CET

ESI Humane Borders 2

The Australian model and the future of protection

Please join us for a discussion of the future of the refugee convention

and the issues raised by this newsletter.

Zoom Meeting

Meeting ID: 932 3156 2539

Passcode: 009464