Saving lives in the Aegean – Teaching war in School

Dear friends,

Europe is currently witnessing the biggest movement of people across South East Europe since the Balkan wars of the 1990s: the mass migration of mainly Syrian refugees from Turkey to Greece and then on to Germany.

What is to be done? ESI has recently presented a new paper with a concrete proposal to European decision makers:

Why people don't need to drown in the Aegean – A policy proposal

(17 September 2015)

This proposal addresses why neither Angela Merkel's generosity nor Viktor Orban's hostility offer a solution to this crisis. It outlines a strategy that might just work, based on an orderly asylum process and sensible cooperation between the EU and Turkey. The proposal has already attracted considerable attention across German and Austrian media:

- Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Michael Martens, "Auf dem Meer gibt es keine Mauern" ("There are no walls on the sea") (18 September 2015)

- Interview with Gerald Knaus in Deutschlandfunk on ESI's policy proposal (18 September 2015)

- ESI in TV debate on the refugee crisis: Talk im Hangar-7 (17 September 2015)

- Interview with Gerald Knaus in Dnevni Avaz: "Ljudi u EU se boje, jer kolonama ne vide kraj" ("People in the EU are afraid because they cannot see the end of refugee crisis") (17 September 2015)

- Interview with Gerald Knaus on ESI's proposal: Austrian TV (16 September 2015)

- ESI on Bloomberg news: "Clash Blocks Refugees at Greek Frontier as EU Crisis Deepens" (21 August 2015)

Next week we will publish more details on our proposal. We also look forward to feedback and suggestions from all of our readers.

Textbook battles – weapons of mass instruction

|

|

|

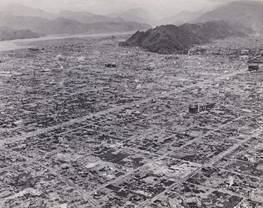

Winning wars: Croatia in 1995 – Japanese city after US firebombing |

|

Nationalists around the world see the role of history as a means to awaken emotions of loyalty. They are particularly concerned that the young are taught to love their nation and to know its enemies. Nationalists do not accept the view that in a democracy history education should prepare students for citizenship in a world where all institutions are imperfect – a world where, unnervingly, even those we admire may be responsible for crimes.

A new ESI Report, supported by Erste Stiftung in Vienna, describes how the clash between different approaches to history education has played out in Croatian history textbooks:

Teaching War – How Croatian schoolbooks changed and why it matters

(16 September 2015)

In Croatia, until 2000, there was only one nationalist textbook in use. Students were taught that Serbs are their historical enemies; that the crimes of the partisans, including mass executions after the Second World War, where committed mainly by Serbs; that there was some good in the policies and ideals of the Ustasha movement as it was committed to an independent Greater Croatia, including Bosnia and Herzegovina; and that there was no need to consider any crimes committed by Croats during any of Croatia's recent wars.

By 2013, when Croatia acceded to the EU, teachers could choose between four textbooks, which offered a much more nuanced picture. This reflected wider changes in how Croats viewed themselves, how they defined citizenship and how they saw their relationship with their neighbours and their Orthodox Serb minority. When Croatia joined the European Union there were four history books in use for the 8th grade. All describe how the Ustasha regime pursued the goal of a national homeland exclusively for Croats. One refers to "Ustasha terror against Serbs, Jews and Roma," another to "persecution and mass killings of the Serbian population," a third to the "genocide of Serbs, Jews and Roma." All mention the racial laws and note that Jews had to wear a yellow star, suffered from expropriations and imprisonment and were murdered in concentration camps. All describe Jasenovac, the largest Croatian concentration camp where Serbs, Jews, Roma and antifascist Croats were killed, giving figures of victims consistent with those given by the US holocaust museum.

How schools teach about wars and about issues such as the bombing of civilians, war crimes or ethnic cleansing sends a signal that goes far beyond the classroom. Modern humanitarian law is equally binding on countries fighting and winning wars of self-defence, as it is on aggressors. A willingness to condemn violations of the laws of war in history textbooks is thus also a litmus test of a country's commitment to international norms. As the British daily The Independent wrote in 2004, advocating an official apology for the carpet bombing of Dresden at the end of the Second World War: "Is it really so hard to understand that you can support a war while objecting to some of the individual war crimes committed during the course of the fighting?" In fact, it is surprisingly hard, even for established democracies such as the United Kingdom or the United States – hard, but essential if war crimes are to become less common in the future.

The debate on how to teach recent history never ends. If Croatian textbooks have changed fast in the past few years, they will change more; the question is not whether but how. Even today, they are under challenge from nationalists. The way these debates play out will have huge significance for Croatia's democracy and its position in the region. Will Croatia's future leaders follow in the path of Putin's Russia, where textbooks have been revised to give a distorted picture of the 20th century?

Will Croatia find itself in endless textbook wars, like Japan and its East Asian neighbours? Or will it look to Germany, where a sustained campaign to come to terms with a complicated past has been key to building previously unimaginable levels of trust among neighbours? In this case Croatia could become an inspiration for a Balkan region that comes to terms with recent history.

Today, textbook authors across the Balkans face the challenge of explaining wars and war crimes, fascism, communism, ethnic cleansing and systematic violations of human rights in their recent past. Some Balkan countries still use textbooks telling stories of a nation surrounded by enemies, with national heroes and foreign villains, periods of suffering and victimhood alternating with military triumphs. Such textbooks transmit distorted ideas of citizenship; and signal to adults the limits of a nation's commitment to human rights and fundamental values, in peacetime and in war.

|

|

|

Croatian textbook authors: |

|

The protagonists in these battles are not generals, but the authors who write textbooks. And the heroes in this tale are teachers and historians who are convinced, as Canadian historian Margaret MacMillan once put it, that "examining the past honestly, whether that is painful for some people or not, is the only way for societies to become mature and to build bridges to others."

Many best wishes,

Gerald Knaus

PS: Excerpts from the Report Teaching War

Greek Secret Schools

|

|

|

"The Secret School" |

|

Nationalist history textbooks also teach the young about friends and enemies. In primary schools, Greek children learn about "secret Greek schools" in the Ottoman Empire, where young children learned Greek and about their religion, in defiance of Turkish oppression. This is taught through a nursery rhyme about such schools, through a discussion of a painting by a 19th century Greek painter ("The Secret School") and sometimes an excursion to a famous wax museum in Ioannina, which depicts life in a secret school. A secret school even made it onto a Drachma bill. Greek historians know that such schools never existed. But when a history textbook clarified this, it was burned by supporters of Golden Dawn, the Greek fascist party, in Constitution Square in the centre of Athens in March 2007. The book in question was only used for one year and then withdrawn, following a massive mobilisation led by the Orthodox Church. Antonis Samaras, then a European parliamentarian and later Greek prime minister (2012-2015), defended the withdrawal of the book, arguing that the point of teaching history in school was the "development of the national consciousness" of Greeks. For those who think like him, history textbooks are weapons of mass instruction in the battle to define national identity.

How to teach the bombing of civilians

Between September 1940 and November 1941, Germany bombed London, Coventry and many other British cities, killing over 60,000 civilians and destroying two million homes. The fighting lasted six years. In the end, Britain and its allies prevailed. In 1946, Winston Churchill, Britain's wartime leader, speaking at Zurich University, repeated Nicholson's message, calling on Europeans to "build a kind of United States of Europe. In this way only will hundreds of millions of toilers be able to regain the simple joys and hopes which make life worth living." Then Churchill put his pen to paper and composed his masterpiece, earning him a Nobel Prize for literature, a multi-volume account of Britain's finest hour: The Second World War.

Seventy years later, the memories of this glorious war are still alive in British debates. But while the narrative of saving European civilisation remains an inspiration, some aspects of Britain's wartime history have given rise to debates similar to those seen in Croatia. One issue in particular has emerged as controversial: the role of the war-time Bomber Command under Air Marshall Arthur Harris. Throughout the war, British (and other allied) pilots carried explosives and incendiary chemical weapons over enemy territory and then dropped them, without much accuracy, on workers, families and houses. They did so across Europe: from Bulgaria to Italy, from occupied France to Germany. A British press briefing referred to the strategy as "deliberate terror bombing." It was a strategy praised by Churchill himself when he met Stalin in Moscow in August 1942:

THE PRIME MINISTER: … As regards the civilian population, we looked upon it as a military target. We sought no mercy and we would show no mercy.

M. STALIN said that was the only way.

THE PRIME MINISTER: said we hoped to shatter twenty German cities as we had shattered Cologne, Lubeck, Dusseldorf, and so on. More and more aeroplanes and bigger and bigger bombs.

By May 1945, the Allies had attacked sixty-one German cities, including massive raids on Hamburg, Berlin and finally Dresden where, in fourteen hours on 13 February 1945, they killed 25,000 to 30,000 people through the deliberate creation of a horrific firestorm. By the end of the war, 131 German cities had been bombed and some 600,000 Germans had been killed by strategic bombing. These were no accidental casualties; the strategic rationale of the campaign was to destroy the morale of the civilian population.

Following the war, the question arose as to how this campaign, the pilots or their commander, Arthur Harris, should be remembered.

|

|

|

Arthur Harris, commander of Bomber Command, in London |

|