ESI in Harvard: Public debate on the recent indictments of top military leaders in Turkey

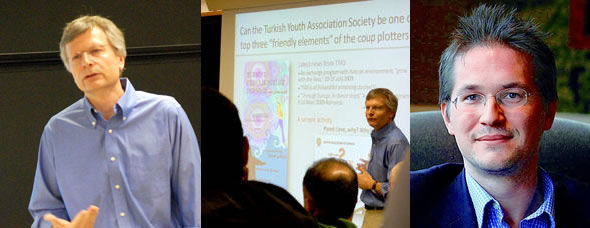

The Carr Center for Human Rights Policy hosted Dani Rodrik, Rafiq Hariri Professor of International Political Economy, Pinar Doğan, public policy lecturer, and ESI's Gerald Knaus, currently a Carr Center fellow, for a panel discussion on the recent arrests and indictments of some of Turkey’s top military leaders and of several hundred other prominent individuals – described as a crisis in Turkish democracy.

Gerald challenged the notion that these cases were sham trials. He pointed out that there were currently eight different court cases and there has not been a single conviction. It thus seems too early to come to any final conclusions. Gerald noted so far that most organisations with a track record of focusing on human rights violations in Turkey for decades considered the trials a step forward for Turkish democracy.

One reason for this is that there is in fact strong evidence that some Turkish generals were considering military interventions in the years 2003 to 2007 against the AKP government. Never before have such claims been seriously investigated. Gerald also noted that there was a string of assassinations (including one blatant case as late as 2005) committed by members of the security forces. Investigating one such assassination (the killing of a judge in 2006) was in fact the starting point for the first Ergenekon-related arrests in 2007. Finally, civil-military relations, which had been based on rules established by the Turkish military itself following successive coups in the past (1960, 1971 and 1980) were being transformed.

Thus, Gerald argued, it is hard to see a systematic deterioration of the rule of law in Turkey. One decade ago human rights organisations described a systematic practice of torture of suspects. There was then a state of near-impunity for security forces engaged in such acts. Gerald raised a different issue. "The fundamental problem in this debate is the issue of regime change, changes in what generals are legally allowed to do" he said. "Even in the late 1990s generals would be calling in journalists to discuss how to topple an elected government. The question is how do you deal with the fact that the rules have now changed?" Turkey is confronting the challenges of transitional justice while this transition is still ongoing.

- Foreign Policy, Pinar Dogan and Dani Rodrik, "How Turkey Manufactured a Coup Plot" (6 April 2010)

- ESI on the future of Turkey's "deep state"

- Newsweek, Zeyno Baran, "The Coming Coup d'Etat" (5 December 2006).

Turkey analyst Zeyno Baran, who is an expert on the Turkish military and has many contacts with its generals, wrote in December 2006 in Newsweek:

"Almost 10 years ago, the Turkish military ousted a popularly elected Islamist prime minister. The circumstances that produced that coup are re-emerging today. Once again, an Islamist is in power. Once again, the generals are muttering angrily about how his government is undermining the secular state—the foundation of modern Turkey. As I rate it, the chances of a military coup in Turkey occurring in 2007 are roughly 50-50 … In recent weeks I have spoken with Turkey's most senior officers. All made clear that, while they would not want to see an interruption in democracy, the military may soon have to step in to protect secularism, without which there cannot be democracy in a majority Muslim country. These are no-nonsense people who mean what they say. Why is this happening? Chiefly because of the European Union. Never mind Cyprus, or the new human-rights laws Turkey has willingly passed under European pressure. The real problem is the EU's core demand: more civilian control over the military."