Red Lines, Rotten Apples and human rights in 2019

- Amnesty, Magnitsky and the power of stories

- How The Hague meeting can be a turning point

- A Commission and a Rotten Apple event

Dear friends,

Hundreds of civil society activists jailed on dubious grounds. Journalists blackmailed with sex tapes, then locked away for years. Whistle-blowers tortured to death in prison, with impunity, indeed promotions, for those who ordered it. Government critics attacked at home and abroad, with radioactive polonium, nerve poison, or knives and saws. All this, and more, has taken place in recent years in Europe.

It is heartening that a European government, the Netherlands, has recently decided that more is needed and more can be done to signal that certain behaviour is wrong and shameful. In April this year, the Dutch parliament adopted a resolution calling for an effective human rights sanction regime at the EU level. This Tuesday, 20 November, the Dutch Foreign Ministry will host senior officials from EU member states and other partners in The Hague to discuss how such a regime might be set up. As the ministry put it in a paper:

"Targeted human rights sanctions could be used against individuals acting in or misusing their official capacity and individuals belonging to non-State actors (i.e. rebel groups). Where geographically limited sanctions regimes aim to change state behaviour and are therefore political in their nature, this thematic regime would be apolitical, purely focused on individuals."

Dutch parliamentarians Sjoerd Sjoerdsma – Pieter Omtzigt – Martijn van Helvert

Last week, in preparation for this meeting, a group of Dutch MPs, together with ESI and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, submitted a concrete proposal with suggestions for the meeting in The Hague:

"The Power of Focus

Proposal for a European Human Rights Entry Ban Commission"

The goal of this proposal is to suggest how the meeting in the Hague might become a turning point and how tangible results are achievable within the next twelve months. One way to do this is for a group of member states to establish an independent commission in The Hague, tasked to present an annual list, based on submissions by NGOs and other institutions, of selected offenders, and recommending to the EU Council and to individual European states to declare (at least) entry bans against them. This could also open the door to further investigations, interpol red notices and other measures.

Amnesty, Magnitsky and the power of stories

Peter Benenson, founder of Amnesty International

When British lawyer Peter Benenson read about the jailing of Portuguese students in 1961 by their dictatorial government, he decided to do something in support of those unjustly imprisoned. His insight was that if a lot of individuals focused sustained attention on a few individual cases, real pressure could be brought to bear. Thus, Amnesty International was born.

When US investor Bill Browder learned about the violent death of his lawyer and whistle-blower Sergei Magnitsky, who had uncovered massive corruption and was beaten to death in a Russian jail in November 2009, he decided to do something, focusing on individual perpetrators behind this and other assaults on human life and dignity. Thus, the global Magnitsky campaign was born.

Both Benenson and Browder realised that in the battle for public attention one has to give a face to the victims and perpetrators, telling strong human stories. It is through stories that children first learn about right and wrong. It is through stories that norms are born, taught and reaffirmed. And it is these norms that then form the basis of any civilisation.

Sergei Magnitsky died on 16 November 2009, beaten to death in captivity in Moscow. Since then the assault on fundamental human rights norms – the bans of torture, extra-judicial executions and political imprisonment – has continued around the globe, with elected politicians praising torture and summary executions from the Philippines to the US to Brazil. Even inside the EU a coalition of parties and leaders is emerging that looks forward with glee to an end of the era of belief in "universal human rights."

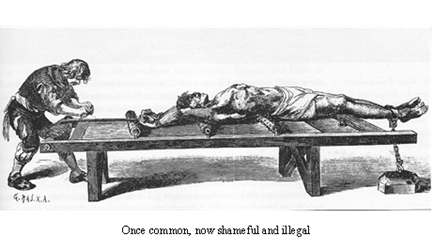

While shaming – exposing publicly that someone is violating accepted norms - is one of the most powerful ways to influence human behaviour, it can only work as long as there are accepted norms to which one can appeal. And these norms need to be reasserted, reaffirmed, restored with constant effort. If left unattended norms slip, slide and decay.

Effective shaming requires an audience. As Jennifer Jacquet wrote in "Is Shame Necessary – New Uses for an Old Tool", there is always a finite amount of attention; in light of "the problem of getting and maintaining that attention, shaming should be used sparingly, so as to maintain its power."

How The Hague meeting can be a turning point

This is the right moment for European democracies to send a strong signal that certain red lines should not be crossed and that certain types of behaviour are intolerable and unacceptable. To achieve this the Dutch invitation proposes:

"the creation of a EU global human rights sanctions regime enabling the EU to impose restrictive measures … against any individual responsible for, involved in or who otherwise assists, encourages, finances, induces or contributes to the planning, directing, or committing of gross violations and abuses of internationally recognized human rights, without geographical limits."

This is a timely initiative, but it faces many hurdles. There are five ways in which this effort might fail:

- The first is that there will be no unanimity. For a decision to set up a "human rights sanctions regime" all 28 EU members need to agree. It is likely that this will require lengthy, complex negotiations that might either fail or result in a weak mechanism. A comprehensive sanctions system of this kind is certainly worth aiming for: perhaps it can be achieved, but it is far from certain.

- The second is that, even if a "human rights sanctions regime" is established, it will only be applied rarely and selectively, given the need for all 28 member states to agree to every name to be included. Anyone fearing inclusion on a list, or their government, will know that they need to lobby only one member state to threaten a veto to be safe.

- The third is that bans are adopted but then overturned by the EU Court of Justice. In recent years the EU's record on this has improved, though this is still a serious risk: until now, the EU Council has lost on average one in two cases before the courts, mostly due to insufficient evidence of what the listed individual is blamed for.

- The fourth risk is a lack of perceived legitimacy. Imagine that everything works as planned – but the result is an obviously "political list" because perpetrators from certain countries with which individual member states have good relations never appear among those listed.

- The final risk is a lack of attention: the EU Council presents a credible list of human rights violators from different countries with strong evidence, but this only captures the attention of the media and public for one fleeting moment.

However, no single EU member state can veto efforts by others to identify human rights offenders, in a credible, thorough and transparent process, and to generate attention for what they have done. Getting attention for egregious human rights violations is important – governments and institutions only reinforce norms and values, if their actions in their defence are visible – but it can also be difficult. There are, however, lessons that can be learnt from other institutions, from the Swedish Academy (and its Nobel ceremonies, highlighting advances in science and other categories) to the American Motion Pictures Academy (and its Oscars used to promote movies). The key ingredients are focus, stories, emotions and regularity. These need to be used to publicise the commitment of European governments to core human rights.

A Commission and a Rotten Apple event

As shaming requires an audience, European states can help create one and highlight a specific number of perpetrators to be put forward for (at least) travel bans to the European Union and other European states once every year at a regular event. One might envisage a Rotten Apple event taking place in The Hague for the first time in October 2019 as follows:

A European Human Rights Travel Ban Commission, set up by a group of European states, invites the media and members of the public to an annual event. This Commission, consisting of three highly respected commissioners (former senior judges, Ombudspersons, prominent human rights professionals) identifies and presents names and stories of at least five perpetrators of serious human rights abuses. At the event, foreign ministers and senior officials from European countries which have created and back this independent body, speak about the importance of human rights norms and affirm their commitment to uphold red lines. Victims of abuse speak out about the consequences of violations and the importance of solidarity. The public is educated with films and background material about the specific norms on which European democracy rests and which have been violated. The media are invited to report on well-researched, strong human stories. In presenting specific perpetrators of violations of human rights such an independent institution reasserts, year after year, that certain types of behaviour remain unacceptable and shameful: that such egregious violations as the imprisonment of political opponents, disappearances, torture and extra-judicial executions cannot be tolerated.

To get there before October 2019 the following steps are required:

- The Dutch government invites other European governments to establish an independent human rights entry ban commission right away. Its task will be to identify each year a limited number of human rights violators, whom the EU (and the other contributing non-EU states) should consider for (at least) admission bans. The commission should focus on particularly alarming cases that illustrate grave human rights violations such as torture, political imprisonment and extra-judicial killings. Communication will be central. This requires that the commission chooses only a few cases every year. Less is more when it comes to public attention.

- The commission is headed by a board of three distinguished former senior judges and human rights practitioners of high credibility. It employs a small team of analysts with legal expertise and communication skills. It accepts proposals from human rights NGOs, lawyers, victim families and governments or governmental organisations, taking advantage of existing information. They need to fill out a detailed questionnaire. The commission screens the proposals and asks for additional information as needed, making sure that the evidence can stand up to court scrutiny. The commission also sees to it that these cases represent particularly gross violations or illustrate underlying problems; and it would allow those concerned to respond to the allegations to ensure due process.

- At least once a year, the commission presents its list of selected offenders to the public and recommends to the EU Council and to individual European states to declare (at least) entry bans against them. At EU level, entry bans do not require an EU Regulation in addition to the Council Decision and are easy to implement. The result of the debate and vote in the Council should be recorded and made public.

- The running costs of such an operation would be in the range of 400,000 Euro per year. In organisational terms, the commission could emulate the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). Since 2013, the EED has provided grants to pro-democracy groups in the EU's neighbourhood. Legally it is a Belgian non-profit association, financed from voluntary contributions by EU member states. The European Parliament is involved in running the EED as well.

- At least initially, the commission might want to concentrate on violations in wider Europe and Eurasia. Under the EU Treaty, the EU is committed to upholding the European Convention on Human Rights and the 1990 Paris Charter, which bind all OSCE member countries.

- Even if the EU does not declare the recommended entry bans, many individual member states and other European countries could; and the commission itself would have created a debate about human rights violations that should not be ignored. Finding unanimity is much more likely this way.

- This strategy complements ongoing efforts by the European Parliament and those EU member states that have, or which support, sanctions to honour the memory of Sergei Magnitsky. It is a strategy that can be pursued without prejudice to the push for a standing EU targeted sanctions regime. It would continue to work well – serving a distinct purpose – in parallel to such a system.

This mechanism would help overcome the hurdle created by the unanimity requirement for sanctions (whether travel bans or asset freezes) in the European Union. The publicity would reduce the likelihood of vetoes by individual member states to these names. It would also make it much harder to put diplomatic pressure on individual member states. And if there are vetoes this would ensure that even more attention would be paid to these cases and even more questions asked of any government that insists that a perpetrator of well-documented violations should NOT be banned from travelling to the EU.

Setting up this mechanism would not require any changes to current EU rules and legislation. It would complement any other human rights sanctions regime which member states want to set up. It would not stop the EU adopting – as it has a number of times in the past – country-specific human rights sanctions (which currently target individuals in Venezuela, Iran, Myanmar and Belarus). It would complement individual countries adopting their own Magnitsky legislation, as the three Baltic states have already done.

Getting this process up and running would require only a group of European governments to commit to it. This core group of likeminded European states might then meet regularly to debate and exchange notes on other questions concerning human rights sanctions. They establish a robust, transparent and principled process for the imposition of targeted sanctions and lay down a visible marker of their commitment to human rights red-lines to both a European and a global public. This is both desirable and doable.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

The European Stability Initiative is being supported by Stiftung Mercator

A project of ESI, the Norwegian Helsinki Committee and human rights defenders

Alexandra Stiglmayer, ESI senior analyst – Bjorn Engesland, secretary general NHC – Anar Mammadli, winner of Council of Europe Havel Prize 2014 – Rasul Jafarov, winner of the NHC Andrei Sakharov Freedom Award 2014

ANNEX: 14 November paper

THE POWER OF FOCUS

PROPOSAL FOR A EUROPEAN HUMAN RIGHTS ENTRY BAN COMMISSION

Today there is an urgent need to defend key human rights norms, such as the bans on torture, on political imprisonment and on extra-judicial killings. Leaders in many countries are questioning these norms and the international treaties that protect them; in others they are violated with impunity. European democracies have an interest to send a strong message to human rights violators and the wider public that these actions remain wrong and shameful.

European governments have long supported human rights. In the 1950s, they drafted and ratified the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. In the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, EU member states guarantee all these rights to their citizens. The EU Treaty also commits EU governments to promoting worldwide human rights, the rule of law, democracy and the principles of international law.

One effective way to do this is to highlight cases where red lines have been crossed without accountability; to point the finger at the perpetrators and those responsible for it; and to declare entry bans and asset freezes against them. The message that an admission ban sends is strong, simple and clear: you are no longer welcome in our society because of what you have done.

The EU and other European democracies already have legislation that allows banning foreigners due to human rights violations. During the last two decades, the EU has imposed entry bans and asset freezes against individuals to address human rights situations in countries such as Iran, Myanmar, Venezuela, the D.R. Congo, Belarus, Uzbekistan and others.

In April 2018, we took the initiative in the Dutch Lower House to task the Dutch government to help establish sanctions at the European level, as well as in the Netherlands against Russian officials that are responsible for the detention, torture and death in prison of Russian lawyer Sergei Magnitsky in 2009. The resolution we proposed was accepted.

Today we want to build on this and offer a concrete way forward with a realistic proposal for more effective and more systematic sanctions against human rights offenders.

By declaring an entry ban against a human rights offender, European governments acknowledge that a serious violation of rights has occurred. In this way we demonstrate solidarity with victims of abuse, and with embattled human rights defenders across the world. We also convey an important message about the values that we seek to uphold. The exposure may lead to a change in the offender’s behaviour and deter others from doing something similar. But even when this does not happen, human rights entry bans fulfil a crucial function; they reassert publicly the norms on which our civilisation rests.

However, to reach these objectives requires that a wider public pays attention. It requires audiences. Entry bans must capture the attention of the public to educate. They must also be noticed in the offender’s society as the basic precondition to set into motion the desired process of exclusion, shame and change in behaviour.

Until today, when the EU or governments have listed human rights violators for entry bans, they have simply published lists of names, often dozens, who have drowned in anonymity. They have failed to explain what these people have done concretely and which norms they have violated. They have directed little attention to the individual stories.

Public attention is also crucial for another reason: admission bans and asset freezes require the unanimous agreement of all 28 EU member states. As a result, many proposals for such measures by some member states have been rejected by others, often due to bilateral considerations. The Dutch proposal for a new sanctions regime for human rights offenders is in danger of suffering the same fate. Making clear to a wider public why a limited number of specific individuals should be banned even before the Council takes a decision makes it much more likely to achieve the necessary agreement.

Signed by:

Pieter Omtzigt, Member of Parliament in the Netherlands & of the Legal Affairs Committee of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

Martijn van Helvert, Member of Parliament in the Netherlands

Sjoerd Sjoerdsma, Member of Parliament in the Netherlands

Bjørn Engesland, Secretary General, Norwegian Helsinki Committee

Gerald Knaus, Chairman, European Stability Initiative