The Lausanne Principle: Multiethnicity, Territory and the Future of Kosovo's Serbs

"As from the 1st May, 1923, there shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Muslim religion established in Greek territory. These persons shall not return to live in Turkey or Greece respectively without the authorisation of the Turkish Government or of the Greek Government respectively."

Treaty of Lausanne, 1923

Some international reactions

- Jim Judah, "Serbian Returns to Kosovo not impossible, says report" (July 6th 2004)

- Neue Züricher Zeitung, "Wer soll wo in Kosovo wohnen?" (August 10th 2004)

Five years into the international administration of Kosovo, two violent days in March 2004 have sorely tested the international commitment to a multiethnic Kosovo. Directed against Kosovo's minorities and against the international mission itself, the violence has left many wondering whether UNMIK has the capacity to achieve its objectives in the face of open resistance.

This is a dangerous moment for international policy in the region. The urgent priority for the Kosovo mission and the incoming SRSG is to reaffirm the international commitment to multiethnic society, at both the diplomatic and the practical level.

This paper argues that the policies needed in response to the March riots must be based on the practical needs of Serbs living in Kosovo today. The paper finds that the current reality of Kosovo Serbs differs from the common perception in important ways. There are still nearly 130,000 Serbs living in Kosovo today, representing two-thirds of the pre-war Serb population. Of these, two-thirds (75,000) are living south of the River Ibar in Albanian-majority areas. Almost all of the urban Serbs have left, with North Mitrovica now the last remaining urban outpost. However, most of the rural Serbs have never left their homes. The reality of Kosovo Serbs today is small communities of subsistence farmers scattered widely across Kosovo.

Against this background, the paper argues that the Serbian government's plan for creating autonomous Serb enclaves in Kosovo is dangerously flawed. Kosovo Serbs cannot be separated into enclaves without mass displacement of both Serbs and Albanians, increasing hostility and further compromising the security of Serbs. Any attempt to implement this vision leads inevitably towards renewed violence. If, as seems likely, the Belgrade plan is a tactical ploy aimed at securing the partition of Kosovo, it amounts to a betrayal of a large majority of Kosovo Serbs.

The paper argues that a sustainable solution for Kosovo cannot be based upon the Lausanne principle: the negotiated exchange of territory and population common in post-conflict settlements in the Balkans in the early 20th century. Serb communities in Kosovo will only be viable if the territory remains unified and Serbs are able to participate as full citizens in multiethnic institutions. The stakes are extremely high, both for Kosovo Serbs and for the international community, whose entire strategy in the region over the past decade has been based on a commitment to multiethnic society.

The essence of the 'Standards before Status' approach is that Kosovo's institutions of self-government must take responsibility for ensuring that minority communities can live in Kosovo in safety and dignity. The paper proposes three practical measures for making this Standard a reality:

- a redoubling of efforts on return and repossession of property, with a view to completing the process by the end of 2005;

- ensuring that multiethnic security structures in Kosovo are strengthened, properly equipped and placed under the political responsibility of the elected Kosovo government, through a ministry of public security;

- carefully targeted reform of local government structures to ensure that Kosovo Serbs receive adequate public services in the places and circumstances in which they now live.

In addition, the paper argues that a renewed effort to overcome the division of Mitrovica would be the most positive response to the March riots, removing Kosovo's most dangerous flashpoint and opening up possibilities for negotiated solutions on a range of highly contentious issues.

A fundamental precondition, however, is that the international community explicitly rule out any solution for Kosovo based on territorial bargains or the expulsion of minority populations. Whatever its final status, Kosovo must remain whole and undivided, providing a safe home for all of its traditional communities. The Contact Group and the European Union should serve notice that any partition scheme will be vetoed in the Security Council. They should also serve notice that an ethnically cleansed Kosovo will never be seen as fit for sovereignty. Let it be made clear to everyone concerned that the anti-Lausanne consensus that guides policy in Europe today is too solid to be shaken by an angry mob.

Five years into the UN administration of Kosovo, two violent days in March 2004 sorely tested the most basic principle of international policy in the Balkans – the commitment to multiethnic society. The riots of 17 and 18 March, directed by ethnic Albanian hardliners against Kosovo's minorities and the international mission, came as a shock. Crowds turned on UNMIK administrative buildings, destroyed numerous UN police vehicles and engaged KFOR in street battles. The few remaining Serbs living in the large urban centres (Pristina, Gnjilane, Prizren) were driven out. A number of returnee villages, including Belo Polje near Pec and Svinjare near Mitrovica, went up in flames. Churches across Kosovo, abandoned by the KFOR troops supposed to guard them, were destroyed by mobs. Two months after the riots, 2,638 of the newly displaced had been unable to return to their homes.

Caught by surprise by the scale of the challenge to its authority, the international mission is still reeling. Its faith in its own goals and strategies has been undermined. As hazard pay is reintroduced and evacuation plans are dusted up, UNMIK personnel risk losing confidence in their ability to implement the core mandate of the mission.

The riots were a direct attack on multiethnic society in Kosovo. They showed the continuing influence of extremists willing and able to orchestrate violence for political ends. Alarmingly, they also demonstrated the susceptibility of large numbers of young Albanians to their influence, with up to 50,000 individuals participating in the riots according to KFOR estimates.

For the Serbian government, the eruption of violence was proof of what many in Belgrade had been arguing for years: that multiethnicity in Kosovo is impossible. One commentator stated that it would take "irresponsible naivety or ruthless lack of interest to claim that a multiethnic Kosovo under the terror of the Albanian majority is a possible and achievable project." Prime Minister Kostunica declared:

"I trust it is clear to everyone that a multiethnic paradise in Kosovo is unworkable, more so even than the communist utopia of a society without classes. If that were still feasible, a multiethnic society in Kosovo is not."

Many outside voices concurred. As one commentator put it in the Financial Times:

"The EU's own competing vision of a multi-ethnic Kosovo has no demographic base… Partition looks like one of only two solutions that will permit any Serbs to remain in Kosovo at all. The other is reintroducing Serbian security forces into Kosovo."

Never before has the basic international goal in Kosovo – to create a multiethnic and democratic society – been as openly questioned as now.

This paper examines the reality of life for Serbs in Kosovo today. It reveals a number of basic demographic facts which differ dramatically from common perceptions. Based on this reality, it takes a hard look at recent proposals by the Serbian government for the separation of Kosovo Serbs into their own enclaves. It also considers the option of partition of Kosovo, which has once again become attractive to some observers. It finds that territorial solutions such as these would exacerbate security problems and result in the betrayal of a large majority of Kosovo Serbs.

The paper sets out an alternative strategy for how the international community might reaffirm and practically implement its commitment to a multiethnic Kosovo. It proposes a re-energising of the "Standards before Status" policy, based on:

- a redoubling of efforts on return and repossession of property, with a view to completing the process by the end of 2005;

- ensuring that multiethnic security structures in Kosovo are strengthened, properly equipped and placed under the political responsibility of the elected Kosovo government, through a multiethnic ministry of public security;

- carefully targeted reform of local government structures to ensure that Kosovo Serbs receive adequate public services in the places and circumstances in which they now live.

However, none of these programmes are achievable unless the international community clearly rules out the possibility of partition of Kosovo.

Although the March violence left them feeling more insecure, the majority of Kosovo Serbs continue to live and work on their traditional lands, side by side with the Albanian majority. Kosovo in spring 2004 is no multiethnic paradise, but it is certainly a multiethnic society. To the Serbs of Strpce, Gnjilane, Kamenica or Gracanica, multiethnicity is a simple demographic fact. Large parts of rural Kosovo are multiethnic because the people who live there have remained in their homes throughout the turmoil of the past decade.

While there are no official population figures in Kosovo, both Serbian and Kosovo government data suggest that there are currently around 130,000 Serbs resident in Kosovo. The Belgrade-based Kosovo Coordination Centre (CCK), which is the Serbian administrative body responsible for Kosovo affairs, published a detailed report in January 2003 which gives a figure of 129,474 Serbs in Kosovo in 2002. This corresponds closely with ESI estimates based on primary school enrolment figures from the Kosovo Ministry for Education. There are 14,368 pupils in Serb-language primary schools in Kosovo in 2004. Using data on the age structure of Kosovo Serbs from a number of post-war surveys, this suggests a total Serb population of 128,000.

According to the last Yugoslav census, there were 194,000 Serbs resident in Kosovo in 1991. During the 1980s, the number of Kosovo Serbs had declined. It is unlikely that the number of Serbs increased again during the 1990s. In fact, during the 1990s, the Serbian government felt compelled to introduce various measures aimed at stemming the emigration of Serbs from Kosovo.

The extent of Serb displacement from Kosovo is therefore likely to be around 65,000. Contrary to a widespread perception, two-thirds of the pre-war Kosovo Serb population actually remain in Kosovo.

|

Municipality |

Primary school pupils |

Percentage of total |

|

Gjilan / Gnjilane |

1,936 |

13.5 |

|

Leposaviq / Leposavic |

1,819 |

12.7 |

|

North Mitrovica |

1,630 |

11.3 |

|

Kamenice / Kamenica |

1,325 |

9.2 |

|

Prishtina / Pristina |

1,229 |

8.6 |

|

Shterpce / Strpce / |

1,217 |

8.5 |

|

Zveqan Zvecan / |

981 |

6.8 |

|

Lipjan / Lipljan |

969 |

6.7 |

|

Zubin Potok |

869 |

6.0 |

|

Vushtrri / Vucitrn |

619 |

4.3 |

|

Viti / Vitina |

474 |

3.3 |

|

Obiliq / Obilic |

408 |

2.8 |

|

Fushe Kosove/Kosovo Polje |

348 |

2.4 |

|

Peja / Pec |

180 |

1.3 |

|

Novoberde / Novo Brdo / |

164 |

1.1 |

|

Rahovec / Orahovac |

137 |

1 |

|

Istog / Istok |

33 |

0.2 |

|

Skenderaj / Srbica |

30 |

0.2 |

|

Total |

14,368 |

100.0 |

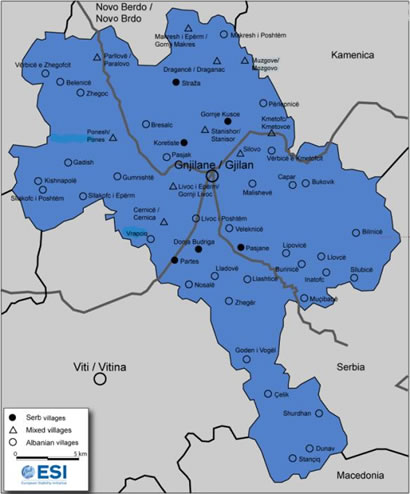

The CCK believes that most Serbs in Kosovo live north of the River Ibar, which runs through Mitrovica. This is not borne out by available data. Because children attend primary school locally, enrolment figures provide a good picture of the distribution of Serbs around Kosovo. As Table 1 suggests, only a third of Kosovo Serbs live north of the Ibar, in the municipalities of Zvecan, Zubin Potok and Leposavic and in North Mitrovica. The remainder – upwards of 75,000 people – are in the Albanian-majority south. There are concentrations of Serbs in the municipalities of Gnjilane, Novo Brdo, Viti and Kamenica in the south-east, in Serb-majority Strpce in the south, and in the settlements surrounding Gracanica near Pristina. Thus, contrary to another widespread perception, almost two thirds of the present resident Serb population in Kosovo live south of the river Ibar.

Perhaps the most important fact that emerges from the data is the striking difference between urban and rural Serbs. Today, there is not a single Serb-language primary school in any of the larger urban centres. Of the 63 Serb primary schools in Kosovo, 47 are located in villages with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants. A large majority of Kosovo Serbs are living in small villages scattered widely across Kosovo.

Before the 1999 war, there were two distinct communities of Kosovo Serbs, living in very different social and economic conditions. In the rural areas, people lived in small communities, often on lands their families had worked for generations. As with peasant workers throughout the former Yugoslavia, these were politically marginal communities which neither expected nor received much from the state. By contrast, urban Serbs in Pristina and the larger towns held the pick of working positions in government and socially owned enterprises. They enjoyed the status and privileges that came from close association with the state – particularly after 1989, when Albanians were purged from public-sector employment.

The Kosovo war and the withdrawal of the Serbian state have affected rural and urban Serb communities in very different ways. With the exception of a last outpost in North Mitrovica, the world of urban Serbs has entirely disappeared. There are no more than a handful of Serbs left in Pristina, Pec, Prizren or any of the other larger towns. By contrast, a large majority of rural Serbs never left Kosovo, even during the most turbulent period in 1999/2000. Most are living a life of subsistence agriculture, and though conditions are hard, they are relatively self-sufficient. Only in the Metohija/Dukajini region was there a substantial exodus of both the rural and urban population.

In short, the effect of the 1999 war was that almost all urban Serbs left, leaving North Mitrovica as the last remaining urban outpost. However, the vast majority of rural Serbs stayed.

Kosovo's remaining Serb communities vary considerable in geographical, economic and political conditions. As the last urban enclave, North Mitrovica survives through massive subsidies in the form of public-sector salaries and social transfers, coming from both the Serbian and the Kosovo budgets. Politics in North Mitrovica are directed towards Belgrade, and aimed at securing continuing support. Wage employment in North Mitrovica comes almost exclusively from its public institutions, in particular the university and hospital. These are funded from Belgrade, with many of the professional staff receiving double salaries as an incentive to remain in Kosovo. There is almost no other economic activity, other than small retailers. This leaves the remaining urban communities in a highly precarious position; if a change in the political climate brought these subsidies to an end, it would trigger a rapid exodus of population. Even if present subsidies continue, the lack of public and private investment makes life increasingly difficult, as infrastructure and public housing decays and employment declines. Gracanica, a village near Pristina surrounding a famous Orthodox monastery, has also emerged since 1999 as a small public service centre for Kosovo Serbs, boasting a university faculty, a secondary school, health facilities and a small private sector. Strpce, the main Serb-majority town in the south, has seen most of its former socially-owned companies cease production.

The municipality of Gnjilane, home to the largest community of Kosovo Serbs south of the Ibar, illustrates dramatically the different fates of rural and urban Serbs in post-war Kosovo. According to the last Yugoslav census, there were 19,370 Serbs in the municipality in 1991, of whom just under 6,000 lived in the town. Today, the urban Serbs have gone; according to local Serb representatives, there were 250 left before March 2004, and only 25 now. However, with 12,123 Serbs still living in the municipality, it is clear that almost all the rural Serbs have stayed.

Compared to other parts of Kosovo, Gnjilane was spared serious inter-ethnic violence before and during the 1999 war. Following the withdrawal of Serbian police, however, the descent into violence was, according to the OSCE, "swift and widespread." From 10 to 18 July 1999, Serb and Roma housing in Gnjilane town was burnt, and murder and abduction was widespread. By the time the first UN police arrived in August, the urban Serbs had been driven out, together with most of the Roma. Outside the town, however, there are only two villages where significant numbers of Serbs have left: Zhegra, which is now abandoned, and Cernica, which is still partly inhabited.

General security conditions do not offer a sufficient explanation for the different reactions of urban and rural Serbs, particularly since 2000 when conditions stabilised considerably. After all, no village in Gnjilane is particularly remote from the town or neighbouring Albanian communities, and there have been no check-points for several years. The difference must be attributed to other factors. One has been the lack of a mechanism until recent times for reclaiming property in the urban areas. Perhaps the most important factor is the difference in economic position between Gnjilane's urban and rural Serbs.

During the socialist period, Serbs were heavily over-represented in jobs in the public administration and socially owned enterprises. After 1989, when Albanians were purged from public-sector employment, the number of jobs for Serbs increased dramatically. For the first time, serious employment opportunities in socially owned companies were extended to rural Serbs. In the Serb village of Partes near Gnjilane, for example, where there had been hardly any formal employment in the 1980s, by the 1990s around 100 people were travelling by bus each day to jobs in the town. However, rural Serbs remained on their land, and continued to work it. When both white-collar and factory jobs in the public sector disappeared with the withdrawal of the Serbian state, urban Serbs were left with no way of surviving. Rural Serbs in the villages surrounding Gnjilane could return to subsistence farming. This is not an easy life. In most villages, particularly those closer to the town, there is a real shortage of land. In Korestite, for example, some 270 households share only 300 hectares of land – inadequate even for subsistence agriculture. These farmers sell some produce in the Gnjilane market, but remain desperately short of cash income, forcing some households to sell land in small parcels to Albanians from the diaspora. In other places, however, rural families are able to survive through a combination of subsistence agriculture and some cash income from social transfers or diaspora relatives.

Gnjilane's remaining Serbs have managed to reach a working accommodation with the Albanian-dominated municipal institutions. Some 75 former Serb municipal employees now work in the local office of the Serbian-financed Kosovo Coordination Centre, in the village of Gornje Kusce. Other Serbs from surrounding villages have taken up jobs in the administration and in the Kosovo Police Service. The Albanian mayor, Lutfi Haziri, has made a genuine effort to involve local Serb leaders in the running of the municipality, and is on good terms with the local director of the Kosovo Coordination Centre. Though the school system is divided, there is ready access to both Serb- and Albanian-language primary schools throughout the municipality, with the Serb schools and a local health clinic funded jointly by the Kosovo and Serbian budgets. One of the municipality's few functional socially owned enterprises, an outlet of the company Jugoterm, is situated in the Serb village of Donja Budriga, and has just had its debt repaid from the municipal budget. There are daily contacts between the two communities: Serb farmers bring their produce to town to sell to Albanians, and Albanian shopkeepers greet Serb customers in Serbian without hesitation.

In Gnjilane, as in other places in Kosovo, multiethnic society is not an aspiration, but the demographic reality. Though badly shaken by the March riots, the rural Serbs have remained in their homes, just as they did throughout the turmoil of 1999. They stay because, though conditions are harsh, subsistence agriculture makes them relatively self-sufficient, and they have nowhere else to go. So long as they are free of political violence and receive adequate public services, they are likely to stay. Over the longer term, however, we would expect to see emigration of the rural population away from the villages in search of wage employment in urban areas. If there are no opportunities within Kosovo, they will inevitably head for Serbia, as and when economic conditions there allow. The future of Serbs in Kosovo therefore depends upon developing credible alternatives to emigration, such as boosting the productivity of agriculture, creating development opportunities in rural areas and building up urban environments capable of supporting the new generation.

On 2 March 2004, in his first speech to parliament as newly elected prime minister, Vojislav Kostunica, vowing never to permit Kosovo to become independent, presented a programme for the "cantonisation" of Kosovo. The idea was familiar to the Belgrade political establishment. Already in 1998, the respected sociologist Aleksa Djilas, predicting that international pressure would lead to the restoration of Kosovo's autonomy, had concluded that "the solution, if there is still time for one, must include some autonomy inside Kosovo for majority-Serbian regions and the most sacred Serbian holy sites, which together comprise about a quarter of Kosovo." At the same time, Serb historian Dusan Batakovic first presented a cantonisation plan which proposed five rural Serb regions in Kosovo, as well as special administrations for ethnically-mixed towns.

Today, many in Belgrade concur with Djilas that "Kosovo's social and economic problems are so vast that it has to be granted considerable autonomy simply because Serbia cannot afford to subsidise it." On the other hand, there is also widespread agreement that Kosovo Serbs cannot be "ruled over" by Albanians. This leaves only two alternatives: the creation of autonomous Serb enclaves within Kosovo – sometimes referred to as "autonomy within autonomy" – or the partition of Kosovo into a Serbian north and an Albanian south.

On 29 April, the Serbian parliament unanimously approved a more elaborate plan for the territorial autonomy of Kosovo Serbs. The plan's stated objective is to "root out any possibility of a Serb pogrom." It notes that the challenge is twofold. First, Albanian extremism "is so powerful that it literally threatens the physical existence of local Serbs." Second, at present Serbs are scattered throughout Kosovo, making them difficult to defend.

The solution, according to the Belgrade plan, is to separate Kosovo Serbs from the Albanian majority, through a "proper territorial organisation of the province." This would be accomplished by creating five autonomous Serb enclaves within Kosovo, coordinated through a joint regional assembly and executive council. The enclaves would assume broad governance responsibilities, including security (policing), education, health care, social policy, natural and mineral resources, forestry, agriculture and the management and privatisation of social property within their territory. These functions are not easily administered at the local level. Though they do not say so directly, what the authors of the plan appear to have in mind is that Serbian laws would apply in the enclaves, administered by local outlets of central institutions. Although the plan uses the language of "decentralisation", in fact it would place Belgrade at the centre of a highly centralised system of government.

What is most revealing about the plan, however, is its description of how the autonomous regions are to be created. There would be three steps. First, traditional Serb territory would be identified, including all areas in which Serbs were in the majority before the 1999 war, together with religious sites. Next, additional land would be incorporated to connect these territories and make them defensible. Third, this additional territory would be settled by displaced Kosovo Serbs returning from Serbia.

Every step in this sequence is problematic, beginning with the notion of "Serb majority territory". According to the 1991 census (boycotted by Albanians), Serbs formed a majority in only five of Kosovo's thirty municipalities: Strpce, Novo Brdo, Leposavic, Zubin Potok and Zvecan (the latter two were split off from Mitrovica in the 1980s in order to secure a local Serb majority). This continues to be the case today. Three of these municipalities make up the relatively compact Serb-majority area north of the River Ibar. However, Strpce and Novo Brdo are isolated pockets surrounded by Albanian-majority areas. Most importantly, no more than 40 percent of the Serbs currently resident in Kosovo live in these five municipalities. If Serb internally displaced persons in Serbia are counted, the percentage is even lower.

To circumvent this problem, the Belgrade plan stresses the importance of incorporating surrounding territory from Albanian-majority areas.

"The Serbs would be entitled to parts of the territory that link in a natural way Serb-dominated settlements, in which they previously did not make up a majority, but to which the Serbs exiled from their homes during the ethnic cleansing operation tend to return. This is a major precondition for the future areas of territorial autonomy to have the characteristics of a region."

How would this additional territory be acquired? The plan suggests that it would be received as "just compensation" for Serb property in the urban areas, to which return "is not possible in the foreseeable future." How such a compensation mechanism would work in practice is difficult to imagine, since most of the land which the Belgrade plan proposes to acquire is in private ownership, and would have to be seized from Albanian farmers before it could be reallocated.

The most unconvincing assumption behind the proposal is the idea that urban Serbs, who once held prestigious jobs in government and socially owned enterprises, would agree to relocate to a life of subsistence agriculture in rural Kosovo. Some of the plan's authors have referred to the Israeli experience in the West Bank, pointing out that Israel was able to create "artificial" economic units in isolated locations. Others have stressed the precedent of post-Second World War communist Yugoslavia, when central planners "created" new urban centres through massive public investment programmes. The budgetary implications of such schemes have never been considered, but given the persistent economic weakness of Serbia, they are clearly far-fetched.

Even if the plan could be implemented, it is impossible to see how it would result in greater security for Kosovo Serbs south of the Ibar. Between them, the five Serb enclaves would have an enormous frontier, running close to the main Albanian population centres and crossing Kosovo's major transport routes. Anyone travelling through Kosovo would be required to cross backwards and forwards between Serb and Albanian territory – including the security forces themselves, which would constantly pass each other's road blocks. To defend the enclaves, the Belgrade plan envisages the creation of "civil defence forces" – presumably local paramilitary formations armed and funded by Serbia, of the kind that figured prominently in recent Balkan wars. This is indeed a West Bank-type solution, with armed settlers living in fortified villages in constant fear of attack. It is a recipe for conflict, rather than security. One of the Serb enclaves foreseen in the Belgrade plan is the "Kosovo-Morava River Basin District", comprising Novo Brdo, Kamenica and rural areas in Gnjilane and Viti. As Map 1 shows, Gnjilane's six Serb and ten mixed villages surround the town to the north, west and south. Creating a coherent Serb enclave, contiguous with Serbia, would mean including around twenty Albanian villages, while excluding several of the Serb villages. As many farmers within the enclave have barely a hectare of land per household, there is no spare land to offer Serbs resettling from other parts of the municipality, let alone displaced persons from Serbia. The Albanians would presumably have to be driven out or persuaded to leave, in order to acquire the extra land and to ensure that the enclave is "defensible".

The idea of separate police forces to protect Kosovo Serbs also does not stand up to scrutiny. According to the plan's authors, the most pressing need is to protect Kosovo Serbs from crimes committed by Albanian extremists entering the enclaves. In a divided Kosovo, Serb police could not monitor the activities of Albanian extremists, nor carry out arrests in the 'Albanian' territories where they are based. Conversely, a purely Albanian Kosovo Police Service would be unable to investigate a crime scene within the Serb enclaves. It is natural that Kosovo Serbs expect to be served by Serb police officers within a multiethnic force. But if Kosovo is divided into two separate legal jurisdictions, effective policing of inter-ethnic crime becomes impossible.

In the final analysis, the Belgrade plan most resembles the "Serb Krajina Republic" in wartime Croatia. Croatian Serbs fled from their homes across Croatia to live in appropriated housing behind a military frontline. Isolated from the major urban centres and denied freedom of movement, they were totally dependent on Serbia for financial and military support. In the end, the Krajina Serbs were brutally expelled from Croatia when Belgrade reneged on its promise to protect them. Given the demographics of southern Kosovo and the persistent economic weakness of Serbia, any attempt to implement the Belgrade plan would lead to a similar result – a tragic outcome for the rural Serb communities who have remained in their homes throughout the turbulence of the past five years.

The obstacles to implementing the Belgrade plan are so great that it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that it is merely a negotiating ploy – a maximalist position designed to secure a tactical advantage. If so, what is the agenda that underlies it? The terms of the plan itself suggest an answer.

There is only one area of Kosovo where the proposal could be implemented without violent upheavals – the relatively compact Serb-majority area north of the Ibar. As the plan itself notes, being "close to central Serbia", the north of Kosovo is safer and easier to defend than the Kosovo interior. Creating an autonomous province in Northern Kosovo would involve undoing some of UNMIK's recent policy successes, particularly the establishment of a multiethnic court and Kosovo Police Service in North Mitrovica. However, many of the institutions required for an independent administration already exist.

There are those, both among the political class in Belgrade and in the international press, who believe that the complex institutional mechanisms required for "autonomy within autonomy" are impractical, and would rather see a simpler solution: the partition of Kosovo into a fully independent, Albanian south, and a northern part that would remain within Serbia. They believe that this is an outcome on which both sides might agree – the Kosovo government in order to secure independence for most of Kosovo, and the Serbian government as a face-saving compromise.

As one commentator in the Serbian daily Kurir put it: "We should either tell the remaining Kosovo Serbs that they cannot survive there and that they should move to central Serbia, or we should try to divide what still might be divided, thus at least a part of Kosovo really to be part of Serbia." Cedomir Antic, a historian and member of the liberal group G17 Plus, proposed drawing a "green line" as in Cyprus. He suggests a Security Council resolution to divide the province according to the census data from 1991. Antic erroneously assumes that if "the Serbian canton includes the northern part of Kosovo plus the part around Gracanica," then "90 percent of Serbs would enter the entity."

There are also commentators on the international side who consider partition an unavoidable, if not desirable, outcome. As Ian Traynor put it in The Guardian: "The Serbian elite is not so dismayed to see Kosovo Serbs driven out of their villages. It thinks this will reinforce the case for partition. Albanians too may ultimately back a partition that maximises territory and entrenches an independent Kosovo. With a few exceptions they want Kosovo ethnically pure. In the middle stands the NATO-led international administration, which for five years has been pushing a multi-ethnic, multicultural Kosovo that neither side wants."

Those opposed to partition have pointed to the dangers for Presevo or Macedonia, if the international community acquiesces in further border changes. In fact, the most immediate danger is to the many Serbs (up to 75,000) living in the Albanian-majority south. If the international community were to accept partition, caving in to demands for territorial separation from extremists on both sides, it would leave itself in an extremely weak position to protect the minorities left in the south. This is precisely the scenario that would lead to an intensification of mob violence in Kosovo and the expulsion of the remaining Serbs.

It is not likely that the international community will openly acquiesce in the partition of Kosovo, nor even that the Serbian government will officially advocate abandoning the Serbs living in the south of Kosovo. The real danger is that persistent talk of territorial solutions, along the lines of the Belgrade plan, will set in motion a chain of events that will make this outcome inevitable.

At the turn of the 19th century, when the nations of South Eastern Europe were emerging from a crumbling Ottoman empire, state-building was often accompanied by the brutal expulsion of ethnic and religious minorities. When the Great Powers sat together to redraw the map of the region following major conflicts, they considered forcible population exchange to be a legitimate technique for solving "minority questions". In 1913, the treaty that followed the Second Balkan War included a Protocol on the exchange of population. In 1919, Greece and Bulgaria approved a Convention Respecting the Reciprocal Emigration of their Racial Minorities. In 1934, 100,000 Muslims were resettled from (Romanian) Dobrudja to Turkey. It was a brutal approach: solving minority problems by eliminating the minorities themselves.

The most infamous of these agreements was the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the Greek-Turkish war in Asia Minor. At Lausanne, the Greek and Turkish governments and the Great Powers stated as the very first article of the treaty the principle of preventive exchange of population:

"As from the 1st May, 1923, there shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Muslim religion established in Greek territory."

The result was the forced displacement of almost 1.5 million people, destroying communities that had existed since ancient times. While many had already been displaced by conflict, there were still over 200,000 Greeks in Anatolia and more than 354,000 Turks in Greece. Many of these were "prosperous and satisfied, feeling secure and having no desire to abandon their homes." As the Greek prime minister noted at the time, "both the Greek and the Turkish population involved… are protesting against this procedure… and display their dissatisfaction by all the means at their disposal." With the principal of territorial separation accepted at the international level, however, there was nowhere to appeal, and the expulsions continued to their bitter conclusion.

In the first half of the 1990s, the shadow of Lausanne loomed large as Europe's democratic governments met once again to decide the fate of South Eastern Europe. During interminable negotiations on the Bosnian war, the leaders of the warring parties sought to reinforce their territorial claims by expelling minority populations. As one Bosnian observed at the time, "The maps of a divided Bosnia-Herzegovina passed around at international conferences have become more of a continuing cause for the tragedy that has befallen us than a solution." The international community faced a choice between acquiescing in a territorial solution based on ethnic cleansing, or finding a way to reverse the 'facts on the ground' which had emerged from the conflict.

The year 1995, with the horror of the Srebrenica massacre and the signing of the Dayton Agreement, marked both the nadir and a turning point in the international approach to the region. The peace agreement could not immediately reverse the injustices of the war. However, it did create the framework of a multiethnic state, and the promise that those expelled from their homes would be able to choose whether or not to return. Annex 7 of the Dayton Agreement contains a provision that is the exact opposite of Article 1 of the Treaty of Lausanne: "All refugees and displaced persons have the right freely to return to their homes of origin. They shall have the right to have restored to them property of which they were deprived in the course of hostilities."

In the immediate post-war environment in Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the perpetrators of ethnic cleansing still firmly in power, the prospects of reintegrating the communities seemed remote. During 1996, continuing displacement far outnumbered minority returns. In 1998, reconstructed houses were still being torched by angry mobs incited by shadowy figures. Many believed that the idea of restoring a multiethnic Bosnia was a dangerous illusion that would only bring further violence. They argued that the only 'realistic' path to security was the partition of the country.

Yet the international response was remarkable. With every violent attack on returnees, the international determination to restore a multiethnic Bosnia and Herzegovina was strengthened. SFOR took a more vigorous approach to supporting return. International reconstruction programmes were made faster and more flexible. In 1999, an enormous international campaign was launched to implement the property laws that enabled displaced persons to recover homes they had lost during the war. By 2000, the tide had turned. Bosniacs and Croats were returning to homes across Central Bosnia, breaking down the armed enclaves left over from the war. By 2002, Bosniacs were returning in significant numbers across Republika Srpska. By 2004, over 200,000 families (around a million people) had recovered possession of their properties. With the success of the return movement, the vicious ideology of Milosevic, Karadzic and Tudjman was thoroughly discredited. Today, as international troops and police are steadily reduced, it is local, multiethnic police forces which provide security for minorities across Bosnia and Herzegovina.

It appeared that the international community had finally developed a principled and effective answer to the vicious logic of ethnic separation. In Kosovo in 1999 and in the Presevo valley in southern Serbia in 2000, the international community responded decisively. When an armed uprising in Macedonia in 2001 threatened to escalate into civil war, there was an immediate intervention to preserve multiethnic society. Each time, the settlement was founded on the conviction that different ethnic communities are able to live together. There were always some who believed that multiethnicity was naïve, utopian or dangerous, and that partition was the only route to stability. They were, however, disregarded. Not only was ethnic cleansing condemned as abhorrent, but systematic programmes to restore property rights and freedom of movement were developed to reverse the new realities created through violence. The very idea that stability could be achieved through exchange of populations was decisively rejected on both moral and pragmatic grounds. Since Srebrenica, international policy in the Balkans has been based on an anti-Lausanne consensus.

There are those who believe that acquiescing in the partition of Kosovo would be a simpler and more pragmatic solution than continuing to defend multiethnic society. Yet the Belgrade plan or any suggestion of partition are premised on a mass resettlement of population – a miniature version of the population exchanges agreed between Turkey and Greece in Lausanne. They are neither simple nor pragmatic. Forcible expulsions (whether officially sanctioned or carried out by an angry mob) would raise tensions to an impossible degree. The people in question – rural communities of subsistence farmers – have shown throughout the past decade that they are deeply attached to their traditional homes and lands, and would only leave under direct threat of violence. As one student of earlier Balkan population exchanges noted:

"The attachment of the individual to the soil where he was born is so deeply rooted that only the fear of an imminent peril to his life may force him to emigrate… On the basis of past experience, one is forced to conclude that the transfer of populations is intimately connected with the prevalence of extensive political upheavals."

Any territorial exchange could only be accomplished through upheavals more extensive than any Kosovo has seen to date. A solution built upon further ethnic cleansing would be a dramatic failure for one of the most substantial post-conflict interventions ever undertaken, and a huge loss in credibility for the multilateral institutions – the United Nations, NATO, the OSCE and the EU – which are responsible.

It is a measure of the crisis of confidence on the international side that Serbian proposals for ethnic separation were greeted as "a good basis for resuming dialogue" by former Special Representative of the Secretary-General, Harri Holkeri. No longer confident in its ability to defend multiethnic society, the international community is once again flirting with the Lausanne principle. This is a dangerous moment for international policy in the region. Rearticulating a commitment to a multiethnic Kosovo is the most pressing priority for the new SRSG and the wider international community.

The essence of the 'Standards before Status' approach is that it requires Kosovo's institutions of self-government to demonstrate that they are willing and able to protect the rights of all of Kosovo's ethnic communities. This fundamental condition has been somewhat obscured by the tendency to incorporate every possible reform goal into the eight standards and 484 individual actions in the Standards Implementation Plan. However, the basic principle is clear: unless Kosovo is multiethnic, it cannot aspire to independence.

Special Representative Solana has called for a "re-energising" of the Standards before Status policy. In practical terms, this means prioritisation – focusing on the core principle of minority protection and its practical implications. This demands a clear allocation of responsibilities, backed up by close scrutiny and objective measures of progress. It must be immediately obvious whether the achievement of a given standard depends on the international mission, the Kosovo authorities or other actors (such as Belgrade or the Kosovo Serb community).

There are two main fronts on which international action is needed to defend multiethnicity in Kosovo. The first is making sure that all of the refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) who wish to do so have a genuine opportunity to return to their homes. The second is making sure that Kosovo's existing Serb (and other minority) communities – both the scattered village communities and the urban outposts – are able to survive on a long-term basis.

Some of the heaviest criticism directed at UNMIK, in particular from Belgrade, has focused on the failure of displaced Serbs to return to Kosovo. In 2002, the office of (then) President Kostunica was quoted as saying that "only about 100 of more than 200,000 displaced persons have so far returned." In the wake of the March riots, the Parliament of Serbia issued a declaration which concluded:

"The process of return of refugees and internally displaced persons has been completely unsuccessful, since less than two percent of the refugees and internally displaced individuals from the Serbian ethnic community have returned in four years."

The claim that there are 200,000 IDPs from Kosovo in Serbia, representing almost the entire Kosovo Serb population, has become an orthodoxy, even repeated by international officials. It is a constant theme in the speeches of Serbian politicians that Kosovo Serbs have been subject to a relentless campaign of violence since 1999, making return impossible and causing a continuing exodus of Serbs.

The only official figure on displacement of Serbs from Kosovo comes from a registration exercise carried out by the Serbian government in early 2000. The results, published in April 2000, state that there were 187,129 IDPs from Kosovo, of whom 141,396 were Serbs, 19,551 were Roma and 7,748 were Montenegrins.

|

Source |

Number |

|

Serbian Government registration (April 2000) |

141,396 |

|

Kosovo Co-ordination Centre Report (January 2003) |

110,287 |

|

ESI estimates (based on 1991 census; CCK population data; primary school enrolments) |

65,000 |

However, the limited hard information available from within Kosovo paints a very different picture. As we have already pointed out, if one compares the data on the number of Serbs who remain in Kosovo with Yugoslav statistical data from before 1999, the extent of displacement of Serbs from Kosovo is more likely to be in the vicinity of 65,000. This represents around a third of the Kosovo Serb population.

How is such a wide discrepancy possible? It may not be the result of conscious manipulation, though Belgrade politicians and government institutions have an obvious incentive to 'spin' the numbers. In an environment where no official body has carried out a serious survey or analysis, there is a tendency for all actors – including international organisations and both the domestic and international press – to repeat whatever figures have been placed in the public domain, however tentative, unreliable or out of date, until they become a quasi-official consensus.

From the start, the IDPs were scattered widely across Serbia. Fewer than 7 percent moved into collective centres operated by the Serbian government. Most already had accommodation in Serbia, or stayed with friends and relatives, or else rented apartments. The dispersal of the population made it very difficult to track subsequent movement of IDPs, or to verify the numbers produced during the initial registration exercise.

The need for revision of the numbers is revealed by the Montenegrin experience, where a second registration exercise of Kosovo internally displaced persons in September 2003 reduced the original estimate of 29,132 by more than a third, to 18,047. In fact, a document produced by the Kosovo Coordination Centre in January 2003 gave a figure of only 110,287 Kosovo Serb IDPs in Serbia, without further explanation.

UNHCR's own documents repeat the results of the Serbian government registration exercise. UNHCR, which operates on the territory of Serbia by invitation of the government, has not carried out an independent investigation. In the fine print of some of its documents, however, it expresses serious doubts about the official figures.

"The sum of the estimated number of minorities living in Kosovo, and the number of currently registered IDPs in Serbia and Montenegro, results in a figure significantly higher than the minority population that has ever lived in Kosovo… An undetermined number of minority returnees who have returned to Kosovo, including those who left during the NATO bombings but returned immediately after, never de-registered. Realistically, therefore, much lower numbers than those non-Albanians currently registered as IDPs in Serbia are truly IDPs, or remain IDPs in search of a durable solution, or await voluntary return."

The scale of the initial displacement is one point of contention. The other is how many of the Serbs displaced to Serbia are still potential candidates for return. By any definition, those who choose to sell their property in Kosovo and resettle permanently in Serbia cease to be IDPs. Nobody has made any attempt to track this process. As a result, it is simply impossible to assess the scale of the return task in Kosovo. One thing is clear, however. If it were properly quantified, the task would appear much more feasible than is commonly assumed.

UNMIK has so far taken the position that the numbers are not critical to the process, and that the focus should be on underlying conditions and individual rights. A report from December 2003 responded to the charge that only five percent of IDPs had returned to Kosovo not by challenging the Serbian government numbers, but by arguing that "progress on returns cannot be measured in such an abstract way – it must be based on the actual cases of those who wish to return and have not yet been able to do so for many reasons."

This was a tactical error, whose cost has become particularly apparent in the wake of the March riots. Faced with what seemed an overwhelming caseload, minimal progress and a deteriorating security environment, the temptation for many in the international community is simply to give up on return. Without any way of presenting a more accurate picture, UNMIK is in a weak position to motivate the international mission to believe that success is possible.

Return is indeed not an abstract issue. It can be quantified, with return destinations and axes of displacement marked on a map. It is only by going through this quantification process that the daunting category of "return" disaggregates into specific, achievable tasks. How many potential returns are to the cities, and how many to rural areas? Are return sites concentrated in certain locations, or spread widely across the province? Are displaced persons living in temporary conditions in Serbia, or have they integrated? How many of those claiming their property are in the process of sale?

Accurate numbers and credible analysis would allow the task to be approached with much more conviction. If most Serbs are still in Kosovo, and potential returnees number in the tens rather than the hundreds of thousands, then what seemed an impossible task suddenly becomes achievable. A useful comparison can be drawn to Bosnia and Herzegovina, where a vital tool for mastering a far higher number of claimants were the property law implementation tables. Published monthly in national newspapers, these tables listed the numbers of claims, how many had been resolved and the monthly rate of progress across each of Bosnia's 149 municipalities. Detailed information of this kind reduces a complex process down to discrete tasks, and allows them to be approached methodically. The tables quickly revealed where obstacles were occurring, and enabled a concentration of resources and political pressure into the locations where it was needed. They created positive competition between the municipalities, as each pushed to keep up with the average in order to avoid being labelled as obstructive.

What few of the critics of UNMIK's return strategy appear to have realised is that it is only now, after several years work to build up a return mechanism, that there is a real potential for a breakthrough in this area. For the largest number of potential returnees – urban Serbs displaced from Kosovo's larger towns – it is only quite recently that there has been a credible process for resolving property claims, so as to allow them to repossess urban properties.

For its first three years, the Housing and Property Directorate (HPD), the body created under UNMIK regulations to resolve property disputes, had a painfully slow start, caused by chronic resource shortages, poor management and institutional in-fighting. However, since 2002, the HPD has built up a credible claims process. By April 2004, it had registered a total of 27,033 claims for repossession of property. Of these, 4,185 claims were found to be outside the HPD's jurisdiction (usually because the property was destroyed and nobody was living in it) and 1,634 claims were withdrawn by the claimant after successful mediation. In 9,979 cases, the Claims Commission has issued a formal ruling on property title, leaving 11,235 claims (just over 40 percent) still to be decided.

After a legal determination is made, the HPD contacts the claimant to ask what should be done with the property. This process is still at an early stage. The HPD has received only 1,939 responses from its claimants. Some ask for an eviction to enable them to repossess the property, some allow the HPD to use the property temporarily for humanitarian purposes, and others inform the HPD that they have resolved their problem independently and do not need to proceed. It appears that many claimants have already sold their property, or are going through the claims process in order to do so. However, the HPD does not attempt to track this practice, and there is simply no hard information to suggest how widespread it may be in different parts of Kosovo.

The HPD process is therefore only just reaching the point where it could make a real difference. Seventy-one percent of the HPD's caseload (19,275 claims) are still 'live' – that is, the claimant may be a candidate for return.

In addition, there is continued potential for return to rural areas. With close to 100,000 Serbs still living in rural Kosovo, it is clear that the security problems are not insurmountable. The Kosovo Coordination Centre has produced a map marking actual and potential return sites in fifteen Albanian-majority municipalities in Kosovo. It shows 19 villages where return is underway, and another 66 where return movements are planned. The international mission needs to develop a complete map of potential return destinations, and donors should respond with reconstruction programmes rapid and flexible enough to exploit return opportunities as they arise.

It is now critical that the international community rebounds from the March riots with intensified efforts to promote return. It needs to quantify and map the process, separate it into its components parts, clearly assign responsibilities and ensure that the process is pursued to completion. KFOR should demonstrate its commitment to making the return process work. There needs to be a mechanism to identify potential returnees to the urban areas among the HPD claimants, and to encourage and support them. There should be "return completion" maps drawn up for each municipality in Kosovo, listing the total number of claims and the total number of potential return to destroyed housing. It is a realistic goal to complete all of the return-related tasks in the Standards Implementation Plan by the end of 2005, and the international mission should make a joint commitment with the Kosovo authorities and the Serbian government to achieving this. By setting clear targets and publicising its efforts to achieve them, the international mission would send a message to potential returnees that giving them a genuine choice as to whether to return to Kosovo remains a central mission objective.

We have noted the large gap between perceptions and reality in the return field. We have also noted that, in the absence of accurate data, it is difficult to focus the efforts of the international community or defend it from its critics.

In fact, one finds a very similar problem in the field of security. According to the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs, since the deployment of KFOR and UNMIK on 10 June 1999, "Albanian terrorists have carried out 6,535 attacks, resulting in the deaths of 1,201 persons," the great majority of which, 991, being Serbs and Montenegrins. There is a widespread perception among Kosovo Serbs – reinforced by constant messages by Serbian authorities and media – that Kosovo is a lawless environment, and that Kosovo Serbs have been victims of a continuous campaign of violence by Albanians since 1999.

The reality described in official statistics is rather different. The sharp violence of late 1999/2000 was followed by a lengthy period of normalisation, when the security situation for minorities greatly improved. Figures published by the UN Civil Police show that in 2002, there were 68 murders in all of Kosovo – about the same number as in Stockholm County, which has a similar population. Only six of the victims were Kosovo Serbs, four of whom were murdered by other Serbs. This left only two cases where the victim and perpetrator were of a different ethnicity – an impressively low rate of interethnic violence for a post-conflict environment. Far from watching Kosovo descend into anarchy, UNMIK Civilian Police and the creation of a Kosovo Police Service had enjoyed considerable success in bringing a very difficult situation under control.

However, over the past year, some disturbing trends have emerged. In 2003, there was a series of attacks on police and international officials which, according to UNMIK, were generally "associated with successful police operations or linked to political events." There was also an increase in crimes against minorities. The total number of Serbs murdered (13) was double that of 2002, although the police has not yet established how many of these cases were politically motivated. In the first half of 2004, the number of interethnic murders obviously increased again.

So how dangerous is Kosovo? Are the security mechanisms failing? As in the return field, the key is to be precise about what exactly is occurring. In the period from 2000 until 2003, the UN police mission and the Kosovo Police Service had succeeded in bringing the crime rate down to peace-time levels. The vast majority of rural Serbs remained in their homes throughout the period. This indicates that the problem is not a sustained crime wave against Serbs, or a general problem of lawlessness.

However, since August 2003, there was an increase in politically motivated crime, culminating in the catastrophic riots of March 2004. The riots demonstrated very starkly that neither the international security structures (UN CIVPOL and KFOR) nor the Kosovo Police Service were able to anticipate or respond to mob violence. Faced with a very clear challenge to their authority, they were quickly overwhelmed. This points to institutional deficiencies and operational failures in a very specific area of policing.

A recent International Crisis Group report on the March riots paints a picture of largely spontaneous protests, motivated by frustration with the international mission and the lack of a political destination for Kosovo, which turned violent under the direction of extremists using the opportunity for a show of strength. It should come as no surprise that Kosovo society remains highly volatile, and that it contains extremist elements willing and able to orchestrate violence for political ends. Kosovo is not the only society facing this kind of security threat. Race riots in Los Angeles in the early 1990s were more deadly than the March 2004 events. Similar problems exist in ethnically-divided Northern Ireland or in the Basque regions of Spain. This kind of political violence poses as serious a threat to future democratic governments in Kosovo as it does to the international mission and to Kosovo's minorities. Clearly, Kosovo needs a police force that is able to meet that threat.

However, when the violence erupted in March, KPS officers had no riot shields or protective equipment. They communicated with one another via open analogue radios, making their operations easy to anticipate. They had inadequate transport, and there was no ambulance service to take care of injured officers. It is not clear that KPS officers had either the training or the contingency plans in place for this kind of threat.

The challenge for UNMIK is therefore to ensure that a genuinely multiethnic KPS is adequately prepared for any repetition of the March violence. There needs to be a detailed (and public) investigation into exactly what went wrong in March, and what are the institutional deficiencies that need to be remedied. There are a number of categories to examine. The first is equipment. For some time, it has been clear that KPS had been starved of essential capital investments. It is not clear how much material, from furniture to communications equipment, the UN police mission is going to leave to KPS after its planned departure in 2006. Efforts to identify the capital investment needs of the KPS over the medium term have until now not led to sufficient funding. There is a real risk that tightening budget constraints within the Kosovo Consolidated Budget will make matters worse in the future.

Second, are Kosovo police numbers adequate for the task? In Northern Ireland, at the height of the Troubles, there were some 13,500 police officers for a population of 1.8 million. Since then, the numbers have been reduced to 7,500, reflecting the decrease in violence. In Kosovo on the eve of the riot, there were 6,252 KPS officers and 3,501 international UN CIVPOL officers. Is this sufficient to meet the threat of political violence? Will the number of KPS officers be increased as the UN mission withdraws? Is there a need to build up more special units to deal with riot control?

Third, do the Kosovo security forces have adequate intelligence capacity to monitor and respond to the activities of extremists? Only Kosovo Albanian security structures have the capacity to confront and control violent elements within Kosovo Albanian society. If the elected Kosovo government does not develop this capacity, then it will remain hostage to extremist elements indefinitely.

The other problem which emerged very clearly from the March riots is the question of political responsibility for the security of minorities. At present, the international mission bears the entire responsibility for security matters in Kosovo, with the chain of command going directly to the head of Pillar I. Even though the UN police mission is entering its final phase, security and minority protection continue to be international "reserve powers", beyond the mandate of Kosovo's Provisional Institutions of Self-Government. There is no Kosovo ministry for public security. The Kosovo Police Service is still formally a part of the international mission, with no independent legal status under Kosovo law.

Since March, it has been clear that, with final authority in the hands of the international mission, the international community is in a weak position to hold the Kosovo government accountable for the security of minorities in Kosovo. This makes it difficult to understand the political rationale behind the Standards Implementation Plan. The security of minorities is, quite properly, a key Standard. The document spells out the objective: "There is no impunity for violators. There are strong measures in place to fight ethnically-motivated crime, as well as economic and financial crime." It lists 89 individual actions which need to be taken to achieve this. However, the responsibilities of Kosovo institutions are all indirect or rhetorical in nature. The Kosovo government is called upon to support UNMIK's Pillar I through "public statements", to "encourage" Kosovo citizens to work with the police, to "condemn" statements likely to incite violence, and to "support" the ICTY. Apart from these statements, the only active commitment of the elected government is to provide a share of the budgetary resources needed for law enforcement. All other responsibilities remain with UNMIK, including investigating crime, creating and managing the Kosovo Police Service, drafting and promulgating policing and criminal legislation, establishing a monitoring team to review investigations of crimes against ethnic minorities, and monitoring the treatment of minorities within the criminal justice system. The division of labour is clear: UNMIK acts, Kosovo institutions issue statements. In this most fundamental of areas, the Standards are in fact a measure of international performance.

As it happens, Kosovo's most senior leaders have been issuing statements. In March, Kosovo Prime Minister Bajram Rexhepi and President Ibrahim Rugova called for restraint, the former even confronting a violent mob in person and persuading it to disperse. Both acted to prevent the funerals in Mitrovica on 21 March from triggering further violence. Other politicians have been less explicit in condemning the riots, and not all the statements have been convincing. However, trying to assess whether or not Kosovo politicians are sincere in their public statements is hardly an effective strategy for improving security.

Lessons from elsewhere in the Balkans have shown that security only improves once local institutions are given direct political responsibility, rather than bypassed with international institutions. This has sometimes involved a leap of faith – for example, allowing Biljana Plavsic, now convicted of war crimes, to become an ally in opening up Republika Srpska to minority return in 1997, or bringing Albanian rebel leaders into the political arena in the immediate aftermath of violence in Macedonia. There was never any doubt that the solution to ethnic tensions in the Presevo valley in Southern Serbia would have to be a more effective, multiethnic Serbian police force.

Though it may seem counter-intuitive to some, the most promising response to increasing security after the March riots would be to begin the process of building up a multiethnic ministry for public security within the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government, with responsibility for a fully domestic KPS. This would make the Kosovo government clearly responsible for fulfilling the most fundamental of all the Standards: guaranteeing the right of minorities to live, travel and work freely throughout Kosovo. It is fully compatible with the "substantial autonomy" promised to Kosovo under Security Council Resolution 1244 – even the cantons in Bosnia have their own interior ministries. Obviously, it will take some time to build up effective, multiethnic institutions, and there will need to be a timeline for the transfer of responsibilities from the international mission to the Kosovo government. The task will be difficult, just as it was difficult in post-conflict Macedonia or Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, the planned withdrawal of the UN police mission means that there is no sustainable alternative. The sooner the process begins, the more time there will be for serious institution-building and an orderly transfer of responsibilities.

The alternative – a major review of the international security structures in Kosovo and the introduction of new international troops and police – would not lead to a sustainable solution. International security structures face on obvious disadvantage in dealing with the specific challenges posed by the March riots. Most KFOR troops are not equipped or trained to confront crowds, and some of the more experienced troops capable of doing so have already left for Afghanistan or Iraq. Internationally led forces face significant difficulty in establishing an effective intelligence function to monitor extremism within Kosovo Albanian society. They also lack the legitimacy of a democratic mandate to counter political violence in the name of the majority.

Instead, there should be a gradual transformation of the international police mission from an executive force to a capacity-building mission, similar to the current missions in Bosnia and Macedonia. NATO troops will remain on hand to intervene to protect minorities if necessary, well beyond the transfer of authority, just as they have in Bosnia. There will need to be robust monitoring of Kosovo institutions, based upon hard information and transparent systems of accountability. Together, these actions would create genuine pressure on the Kosovo government to demonstrate that it is serious about defending multiethnic society and fulfilling the most fundamental of all the Standards.

In recent months, the Serbian government has been presenting its proposals for Kosovo under the label of "decentralisation", rather than the term "cantonisation" previously favoured by Prime Minister Kostunica. This appears to be a rhetorical concession to international sensibilities. Decentralisation has a progressive ring to it, and indeed in 2003 the Council of Europe had presented a proposal for decentralisation in Kosovo through the creation of sub-municipal units. As a matter of fact, the Belgrade plan has nothing in common with the kind of municipal reforms discussed by the Council of Europe. Kostunica himself explained: "no matter what we call it – decentralisation, cantonisation, it makes no difference – some kind of autonomy must be given to Serbs in Kosovo."

However, since March, international officials anxious for a new policy direction have seized upon "decentralisation" as a possible basis for compromise with Belgrade. Some have drawn parallels to the Ohrid Agreement in Macedonia, which incorporated local government reform as an answer to Albanian demands for greater participation in government and a fairer allocation of public resources. Decentralisation in Kosovo has become a topic for discussion at high diplomatic levels and in working groups in the international mission.

Reform of municipal government to reflect the needs of Kosovo's minority communities may be a valuable initiative, but with a number of important caveats. First, it is not an answer to the security needs of Kosovo Serbs. As we have discussed, security can only be improved by creating effective, multiethnic institutions able to operate across the entire territory. Dividing the police or judiciary into different ethnic or territorial components would only weaken the protection of Serbs. Second, if it is to result in meaningful changes for Kosovo Serbs, it must begin from their current needs, rather than from abstract principle. Third, any reform initiative must have genuine support from those who will be required to implement it. This will not be the case if the international community is seen to be negotiating with Belgrade over who controls Kosovo territory.

The Council of Europe document of 2003 begins by noting that the traditional layer of sub-municipal government in Kosovo (called mesna zajednica in Serbian or bashkesia lokale in Albanian) has survived in various forms into the post-war period. The Council of Europe experts proposed building on this tradition by creating 280 "sub-municipal units" (SMUs), each with its own elected council and president. Around 60 of the better-endowed SMUs would take over certain municipal functions ("special delegated powers"), such as civil records, waste disposal, maintaining local roads and managing public property, which they would also perform on behalf of neighbouring SMUs. The borders of the SMUs would be drawn on the basis of geographical features and ethnic ties, but would not usually result in mono-ethnic units. Ethnically mixed SMUs would have special Mediation Committees to resolve disputes. Though the proposal is light on financial details, it suggests that SMUs would be funded through a combination of local revenues and grants from the Kosovo budget.

The Council of Europe plan is not well adapted to the circumstances of Kosovo, and it is difficult to see why it would appeal to Kosovo Serbs at the local level. The authors of the document used the municipality of Gnjilane as an example of how their scheme might work in practice. They proposed that the municipality be merged with neighbouring Novo Brdo (Serb-majority), and then divided into sixteen SMUs. Given the demographics of the area, only one of the resulting SMUs would be all-Serb. The SMUs would gain autonomy over some local services, but these responsibilities would be shared between neighbouring Serb and Albanian villages. Local Serbs would also have to work closely with the Albanian-controlled municipal government, and would obtain most of their funding from the Kosovo budget. Rather than creating self-sufficient local units, it would magnify the points at which the Serb communities would need to negotiate with Albanian-controlled institutions. In places like Gnjilane, where local cooperation works, more elaborate local structures are unnecessary; where cooperation is missing, it is not clear why these reforms would help. In short, the Council of Europe scheme would involve a tremendous amount of institutional reorganisation, absorbing the energies of local government for a long period of time, but in the end would not offer Serb communities any significant increase in local autonomy, as they understand it.

In fact, given that the vast majority of Kosovo Serbs live in underdeveloped rural communities, this form of decentralisation carries serious dangers for them in the longer term. To see the pitfalls, it is enough to look across the border to local government reforms implemented in Macedonia in 1996, when the number of municipalities was increased from 34 to 123. In Macedonia, it is the Albanian population which is predominantly rural. The practical effect of decentralisation was to separate Albanian villages administratively and financially from their traditional urban centres, by making them into separate municipalities. Unable to raise significant revenues from a population of subsistence farmers, the new rural municipalities were left without any credible local government structures. In the municipality of Zajas, for example, home of the guerrilla leader-turned-politician Ali Ahmeti, the administration has only seven staff, and is housed in a temporary shelter no larger than a family house. With an annual budget of €55,000, it delivers barely any services to its 11,600 inhabitants. It looks to central government to provide grants for local infrastructure, but these funding mechanisms are highly inequitable, favouring the politically connected urban centres. In Zajas and many other rural municipalities, the effect of decentralisation was that the state simply disappeared for most practical purposes.

Resentment over the resulting inequity was a contributing cause of the 2001 rebellion in Macedonia. One of the commitments in the Ohrid Agreement, yet to be implemented, was in fact to redraw the municipal boundaries and restructure municipal finances in order to achieve a fairer distribution of resources. In Kosovo, local government has also traditionally been structured so as to link rural areas to the urban centres where political and economic power is concentrated. Kosovo Serbs would be well advised to be wary of any decentralisation plan which in effect left them to their own meagre resources.

So what kind of local institutions are needed to respond to the concrete needs of Kosovo Serbs? In our analysis, there are three dimensions to be considered, corresponding to the different situations in which Kosovo Serbs now live.

First, there are five municipalities in Kosovo which are already Serb-majority, where the interest is in strengthening the existing municipal government, rather than fragmenting it. In recent Kosovo budgets, there has been a progressive increase in transfers to the municipal level, in order to create more effective local administrations. The recent introduction of property tax will over time provide the municipalities with a reliable own-revenue source. However, there are a number of other measures which could be taken to strengthen the autonomy of municipalities. Control over the use of local socially owned land would offer both a source of revenue and an important tool for local development policy. Restoring municipal authority over local public-utility companies, currently administered with considerable difficulty by the Kosovo Trust Agency, would be another useful initiative.

Strengthening existing municipal administrations, as opposed to creating new local structures, has obvious advantages. It is not nearly as disruptive as a large-scale reorganisation, and will therefore offer results much sooner. Most importantly, the interests involved do not break down along ethnic lines. What is good for Strpce and Leposavic should also be attractive to Ferizaj or Gnjilane. In the current political climate, finding reform initiatives that can attract support on all sides of the political spectrum is the only practical way forward.