People Or Territory? A Proposal For Mitrovica

The king therefore said: Bring me a sword. And when they had brought a sword before the king, he said – Divide the living child in two, and give half to the one woman and half to the other.

Old Testament, Third Book of Kings, Chapter 3

At a conference in Wilton Park on 1 February, ESI presented its analysis of Mitrovica's economic and social predicament to Kosovo Albanian and Kosovo Serb leaders, together with a proposal for a way forward in 2004. To balance the fears and concerns on both sides, ESI's Wilton Park proposal consists of a package of measures, to be implemented in parallel during the course of 2004. There are four elements to the package:

- Immediate post-war normalisation: substantial progress in 2004 on freedom of movement and the return of residential property;

- Resolving municipal governance: hand-over of UN authority in Northern Mitrovica to a new, multiethnic municipality of Zvecan-North Mitrovica;

- Reinforcing UNMIK/Kosovo institutions: completing the transformation of the role of the Republic of Serbia in Mitrovica from parallel government to long-term donor; abolishing all remaining parallel law enforcement and judicial institutions.

- Joint economic development strategy for Mitrovica and Zvecan: a commitment by the international community to support a multi-annual development and investment strategy devised and implemented jointly by the two municipalities of Mitrovica and Zvecan.

The Wilton Park event revealed broad agreement among local representatives as to the severe social and economic challenges facing Mitrovica, and on the need for immediate action to reverse the cycle of decline. There was a genuine willingness to search for solutions that would ensure a future for the town, and to explore the potential for a locally-negotiated package agreement along the lines outlined here.

This paper argues that there is scope for a compromise solution acceptable on both sides of the river Ibar, in order to pre-empt the economic and social death of the Mitrovica region. Such a solution would need to come soon, however, while Mitrovica is still able to attract the international attention and resources required for a serious development strategy.

Other towns in South Eastern Europe are suffering from the consequences of de-industrialisation. Other regions of South Eastern Europe suffer from unresolved ethnic tensions. But nowhere else has the combination of the two produced a social and economic crisis as severe as in the twin municipalities of Mitrovica and Zvecan in Northern Kosovo.

The Mitrovica region was modernised and developed on the back of Trepca – a vast industrial complex built up around local lead and zinc mines and processing facilities. Directly or indirectly, Trepca provided most of the region's employment. It provided Mitrovica with a proud industrial identity, shared by Serbs and Albanians alike. However, plagued by poor management and over-employment throughout its history, it became divided as a result of the Kosovo conflict and by 2000 had almost entirely ceased production. With mountains of debt and unresolved property disputes, the future of Trepca is extremely uncertain. The result is a one-company town without its company. This is the most dramatic case of industrial collapse that ESI has found right across the former Yugoslavia.

Until recently, international soldiers and barbed wire separated the 1.5 square kilometres of urban North Mitrovica from the rest of the city south of the river Ibar. There were almost no Serbs left in the South, and few Serbs dared to cross the bridge. In North Mitrovica, small pockets inhabited by Albanians, sometimes no more than a few buildings, were turned into heavily guarded enclaves surrounded by permanent military check-points. These checkpoints have now gone, and the atmosphere in the city has improved significantly over the past year. The Kosovo police service is now patrolling throughout Mitrovica and Zvecan. A regional (UNMIK) court with multiethnic staff and a Kosovo Albanian president is operating in the Serb-majority North.

Freedom of movement, however, is still limited and the dispossession of residential property continues to fuel tensions. There is also no consensus on the future of municipal governance in Mitrovica. In 2002, UNMIK responded to the vacuum of legitimate local institutions in the North by creating a temporary international administration. As a result, North Mitrovica is the only part of Kosovo which remains without elected municipal institutions.

Mitrovica's unresolved political status reinforces its social and economic crisis. Mitrovica has attracted a great deal of international attention and resources, but these have gone for the most part on soldiers, policemen and administrators, rather than development. Faced with an almost complete collapse of its industrial base, living standards in Mitrovica and Zvecan are today sustained by salaries and transfers from four sources: the Kosovo consolidated budget; the budget of the Republic of Serbia; the international community; and remittances from the Kosovo Albanian diaspora.

These external sources of income are the life support for a post-industrial community. Our research has revealed that of 19,000 industrial jobs in Mitrovica municipality in 1986, only 1,300 remain. Many of these jobs are precarious, with salaries paid irregularly. On both sides of the river Ibar, the new private sector is a domain of small shops and kiosks, many of them family businesses generating at best a small cash supplement for the household. There is hardly any local production, except for a handful of low-value items. With no new investment going into the private sector, there is little prospect of new jobs being created.

The public sector dominates the economy of the Mitrovica region. In the South, there are 4,000 jobs on the Kosovo budget, including teachers, policemen, health workers, and 779 Trepca employees who receive a "salary" financed directly from the Kosovo budget. In addition, there are another 8,000 recipients of some kind of pension or social welfare payment. Together with another estimated 450 well-paid international community jobs and an unknown amount of remittances from the diaspora, the public budget is the most important and reliable source of income for the community.

In North Mitrovica and neighbouring Zvecan, the private sector is even weaker, and the reliance on public budgets almost total. The former socialist industries and the private sector together employ fewer than 1,900 people. The most important source of income in the North is the Serbian budget – we estimate that it provides more than 60 percent of total income. Many of the 4,100 jobs on the Serbian budget, including in the university and hospital, come with a Kosovo supplement (Kosovski dodatak) of up to 100 percent of base salary, as an incentive for Serbs to remain in Kosovo. Importantly, however, the North has also become heavily dependent on the Kosovo Consolidated Budget, which is today completely financed from local (Kosovo) tax revenues. In addition to 1,800 public sector jobs in Kosovo institutions, Pristina-based institutions pay pensions, social assistance and Trepca stipends to more than 7,000 people. This amounts to 23 percent of total cash income in North Mitrovica and Zvecan. In fact, the amount of spending from the Kosovo budget per head of population in the North is about 50 percent higher than in the South.

This is the paradox of contemporary Mitrovica. The massive level of external support it receives is closely linked to its unresolved political status. The situation is abnormal and precarious; there is no way of predicting for how long it will continue. This uncertainty means that the people of Mitrovica are unable to convert external support into any real development. Apart from a few new buildings for a Serbian-language university funded by Serbia, there is hardly any public investment. The private sector is likewise unwilling to take the risk of investing in anything larger than small shops and kiosks.

If these transfers were to cease or diminish, the effect on the local population would be devastating. The population of Mitrovica today is less than it was in 1981. If present trends continue, Mitrovica's spiral of economic and social decline will lead to continued massive emigration, leaving the town a ghost of its former self.

i) Immediate post-war normalisation

The pre-condition for any serious development strategy – and for mobilising the outside support which it would require – is to bring to an end the anomalies associated with the post-war period. Two particular issues stand out: the unresolved property rights and the lack of freedom of movement.

Following the recent conflict, thousands of Mitrovica citizens were forced to abandon their homes, which were then occupied by other internally displaced persons. For several years, movement between the north and the south sides of the river became next to impossible without heavy KFOR protection. International security forces, stationed between the communities to prevent violence, ended up reinforcing the reality of a divided community.

However, the division of Mitrovica was never as complete as it appeared to external observers. Many of Mitrovica's Serbs and Albanians had lifelong ties as friends and colleagues, sharing a common identity based around the city's past achievements in the industrial, cultural and sporting realms. It is more common in Mitrovica to find Serbs and Albanians who speak each other's languages than elsewhere in Kosovo. There are nearly 3,000 Albanians, Bosniacs and other minorities still living in the north of the city, including in Mikronaselje, a genuinely multi-ethnic settlement located on the hill overlooking the town from the North.

Experience from across the region shows that ethnic tensions are sustained over a long period only if they are deliberately stoked by politicians. They dissipate most quickly where there is daily contact between the two communities – particularly between former neighbours. The key to overcoming tensions is the restoration of security, property rights and full freedom of movement. Freedom of movement multiplies the points of contact between the communities and sets in motion a process of normalisation which is then very difficult to reverse.

Now that the Kosovo police service is patrolling the entire territory of Mitrovica and Zvecan, the main barrier to freedom of movement is unresolved property disputes. These two issues are intimately linked, as the experience with property return has shown in other parts of Kosovo, as well as in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, more than 210,000 claims for repossession of property have been resolved since the process began in 1998. As larger numbers of people have returned, inter-ethnic violence has declined in parallel.

The scale of the property and return problem in Mitrovica is not nearly as large; given the political commitment of the local authorities, it could be completed within a finite period of time. The Housing and Property Directorate (HPD) has registered 2,553 claims for residential property in Mitrovica – approximately half on each side of the river, representing 10 percent of all claims in Kosovo. Many properties have already been sold. Some 860 claims relate to destroyed property awaiting reconstruction assistance – including a large Roma settlement in the South. In these cases, the challenge is not repossession but reconstruction, for which funding would need to be secured.

In the remaining cases, solutions need to be found for those currently inhabiting claimed properties – alternative accommodation for those who have genuine humanitarian needs; eviction for those who don't. Our research on the population of the region suggests that there is no overall housing shortage in Mitrovica. If local authorities work together with the HPD, they would be able to identify enough alternative housing for genuine humanitarian cases. An essential first step would be the formation of a joint Property Committee, in which local authorities on both sides of the river would work together with HPD and other international institutions to identify and resolve any outstanding obstacles.

|

Location |

Claims registered by HPD |

Out of which identified as destroyed property |

|

Mitrovica |

|

|

|

South |

1,266 |

600 |

|

North |

1,287 |

260 |

|

Zvecan |

32 |

3 |

|

Total |

2,585 |

863 |

The only way to resolve this key issue is to address the resolution of individual property claims systematically and in accordance with the law. The laws and procedures for repossessing property are clear. Now that the humanitarian crisis is over, IDPs cannot be accommodated illegally in other people's homes. Nor can the resolution of this basic legal (and human rights) problem in Mitrovica be made conditional on resolving property problems in other parts of Kosovo – a sure recipe for deadlock. If local authorities on both sides of the city were to launch a concerted campaign, the bulk of the outstanding property claims could be resolved in 2004.

ii) Municipal government in Mitrovica and Zvecan

Resolving property claims and restoring freedom of movement is fundamental to any solution for Mitrovica, and the surest way of setting it on the path to normalisation. It is not, however, sufficient by itself to achieve normalisation.

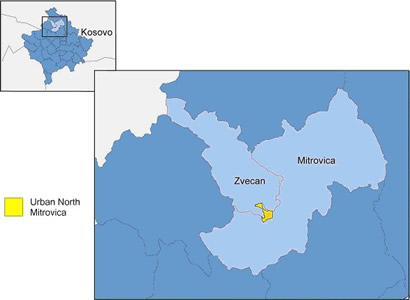

The Northern part of the city of Mitrovica has a population of 16,500 and covers an area of just 1.5 square kilometres. It is the last part of Kosovo left under the direct rule of the United Nations. The issue is: to whom will the UN relinquish control when the international administration comes to an end? What solution would be acceptable to all the different parties concerned?

One of the reasons why there has been such resistance to large-scale return of Albanian properties in the North has been the fear among many Serbs that they would lose control of their last urban area in Kosovo. North Mitrovica is today an important administrative centre for Kosovo Serbs, with a large hospital and university. The provision of public services has become the principal economic function of North Mitrovica. Many Serbs fear that losing control of North Mitrovica and its public institutions will threaten their future in Kosovo.

This poses a serious dilemma for Mitrovica's Serb politicians. Most do not dispute the principle that Albanians have the right to return to their homes. After all, Serbs are actively pursuing the return of their own properties elsewhere in Kosovo. At the same time, the prospect of significant Albanian return to North Mitrovica generates obvious insecurity among the Serb public.

The ESI proposal is to cut this Gordian knot by reassuring the Serb community in North Mitrovica about future municipal governance. We propose that, once the property return process in Mitrovica has began in earnest, the UN administration in North Mitrovica begin to establish a multiethnic administration for a new municipality of Zvecan-North Mitrovica. Once the property return process has come to a successful conclusion, the handover of authority from the UN would take place, together with elections for a new municipal administration in Zvecan-North Mitrovica.

This is a very different proposal from earlier demands by Serb nationalists for "dividing" Mitrovica. A successful return process and a multi-ethnic (bilingual) administration in North Mitrovica/Zvecan would mean that the municipal boundary between these two new municipalities would be just that: a municipal boundary, and not a quasi-border between two different regimes. Since the UN has successfully asserted its jurisdiction over the North, and has made considerable progress in establishing multi-ethnic institutions there – from the regional court and prison to the Kosovo police service – it is well placed to deal with the required institution-building tasks.

Until 1990, Zvecan and Mitrovica municipality were part of a single municipality. Today, nobody proposes that Zvecan should be reintegrated with Mitrovica. Shifting the municipal boundary to the river, while at the same ensuring that the boundary is of purely administrative significance, would both strengthen mutual confidence and make the institution-building tasks much more feasible.

A joint municipal of Zvecan-North Mitrovica would have a Serb majority. It is important to note, however, that this municipality would also have a substantial Albanian population, together with other minorities. To those Kosovo Albanians who recognise the importance of creating a modus vivendi for Serbs in Kosovo, allowing North Mitrovica to join Zvecan would send a signal to the Serb population that they have a future as Kosovo citizens. It is a compromise that makes good political sense, when balanced by an orderly return process and full integration of the North with UNMIK/Kosovo institutions.

iii) UNMIK/Kosovo institutions throughout Kosovo

An essential element of the ESI proposal concerns the role of UNMIK/Kosovo institutions and the government of Serbia in Northern Kosovo. As part of the package solution, parallel courts, inspection services and the Serb district administration (okrug) would be completely dismantled. UNMIK would have to certify that this process was completed before holding elections for the municipality of Zvecan-North Mitrovica.

As late as two years ago, Northern Mitrovica hosted most of the administrative institutions one would have found in any other district in Serbia proper, including the office of the district administration. Even then, however, most of the associated "inspection services" were not operational. There was a general vacuum of authority, illegally and inadequately filled by unofficial "protection" structures such as the infamous bridge watchers in the North.

Many issues surrounding these "parallel" institutions were resolved in 2002 and 2003, following an agreement between SRSG Michael Steiner, the Head of the Kosovo Coordination Centre in Belgrade, Nebojsa Covic, and the then FRY President Vojislav Kostunica. Their agreement led to the extension of the authority of UNMIK/Kosovo institutions across Northern Kosovo. Today, the post-war vacuum of authority has been filled by UNMIK police and the Kosovo Police Service.

The remaining elements of the parallel legal system are:

Police: complete the assertion of authority of UNMIK and multiethnic KPS police across all the territory concerned. This task has already been substantially achieved. Multiethnic police already patrol the ethnically mixed parts of North Mitrovica like Mikronaselje and Bosnjacka Mahala.

Judiciary: complete the dismantling of parallel courts across North Kosovo, including the "district" court which returned from exile in Kraljevo (Serbia), as well as parallel municipal and minor offence courts. This is much easier today than it would have been two years ago. Without Serbian police on the ground to enforce judgments, the courts and inspection services which are not recognised by UNMIK have become marginalised. The number of Serbs using the UNMIK/Kosovo judicial system has risen sharply in recent times, driven by the need for effective enforcement. The parallel Serbian courts no longer hear criminal cases.

Administrative inspectorates: most of these have already disappeared or become inactive due to their lack of enforcement capacity, including the crucial trade, labour and urban planning inspectorates. This can now be formalised.

Okrug: in Serbia, the okrug hosts the inspection services of various central ministries. Without this function, the okrug in Mitrovica has become virtually indistinguishable from the Coordination Centre, which acts as the channel for Serbian financial assistance for Kosovo. This merger can be formalised, and the okrug completely disbanded.

|

|

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

2003 |

|

Misdemeanour Court cases |

117 |

328 |

671 |

964 |

|

Civil lawsuits |

14 |

38 |

69 |

101 |

|

Inheritance matters (Municipal Court Mitrovica) |

8 |

21 |

43 |

87 |

|

Criminal proceedings (District Court) |

29 |

27 |

78 |

122 |

Agreement on these issues would go a long way to clarifying and strengthening the institutional landscape of Northern Kosovo. There would still be issues requiring later resolution at a higher level, in particular the future of health care and the Mitrovica hospital. However, progress on normalisation in Mitrovica need not wait until all these issues are resolved. In fact, if there is a political solution in Mitrovica, the outstanding questions become more of a technical or administrative nature and should be much easier to resolve.

A key part of the package solution, however, would be a common recognition that the Serbian government has a legitimate and indeed very important role to play as a strategic donor. Indeed, it is very much in the interests of Kosovo's government to identify ways in which Serbian support for higher education and health care in the Mitrovica region can continue, to the benefit of all communities. The transformation from parallel government to donor is already well advanced, and the Coordination Centre is actively engaged in a range of development initiatives in North Kosovo. Completing this transformation would be a precondition for the transfer of authority to the municipality of Zvecan-North Mitrovica.

iv) Economic development strategy for Mitrovica and Zvecan

Zvecan and Mitrovica are part of the same economic area and face very similar economic problems. Their fates are intertwined, starting from the fact that the common headquarters of Trepca are in Zvecan, and that many of the managerial staff and engineers required to restart any part of the company are found on both sides of the river Ibar. It makes little sense to pursue separate development strategies.

The elements of a credible economic development strategy for the Mitrovica region were debated extensively at Wilton Park, and will be explored in a forthcoming ESI paper. At Wilton Park, a consensus emerged that a strategy could be based around three primary elements:

- identifying which parts of the Trepca complex have a commercial future and supporting the efforts of the current (multiethnic) Trepca management to revive them;

- converting the financial support Mitrovica receives from the Kosovo and Serbian budgets from consumption into public investment, to qualify for increased co-financing from international donors; and

- laying the foundation for Mitrovica as a centre of excellence in higher education for the region.

There is also an obvious need for investments to maintain and develop essential infrastructure and finance the crucial environmental clean-up.

A shared vision for the development of Mitrovica and Zvecan would create a framework in which the private sector could more confidently make investments and expand employment. Private-sector development would in turn reduce Mitrovica dependence on the public budgets.

It is also clear that a post-industrial Mitrovica is not in a position to fund development initiatives entirely from its own resources. Mitrovica needs to attract continuing external support. Resolving the post-war anomalies in Mitrovica would give donors the confidence to shift resources from security measures to investments in development. International donors could also do a lot to create the incentives for co-operation – for instance by undertaking projects that require co-financing from both the Pristina and the Belgrade budgets, and by helping the two municipalities to establish a common structure for functional economic co-operation.

Since 1999, Mitrovica has been a chip in a larger political game, caught between two sides equally determined not to yield an inch of territory to the other. Yet at the same time, Mitrovica is a community where real people are facing a severe economic and social crisis. The fundamental question for all those attempting to resolve the Mitrovica conundrum is: what matters more – the people or the territory?

This proposal seeks to circumvent the zero-sum logic of territorial conflict which kept Mitrovica divided in recent years. It offers a package solution which answers the real needs of Mitrovica and its people. We believe that a solution to Mitrovica can only emerge from within Mitrovica. As one leading Kosovo Albanian politician put it in Wilton Park: "we cannot wait for the internationals, we cannot wait for other levels. Improving the situation in Mitrovica depends on us."

Who would be the parties to an agreement of the kind outlined here?; There are four institutional players whose agreement would be required: the elected municipal administration which at present administers South Mitrovica; the elected administration in Zvecan; the UN administration in North Mitrovica; and the Kosovo government. It would also be helpful to have the support of the Kosovo Coordination Centre based in Belgrade.

The challenge for Mitrovica and Zvecan and their political representatives is to find a way to capitalise on external support while it is still available, and attract real investment through a credible development strategy. To do this, local politicians need to send a dramatic signal to the outside world. They need to show that home-grown solutions can be found to Mitrovica's unresolved political issues. And they need to do so quickly, before the world's attention is lost.