Ukraine, Europe and a second Treaty of Rome

- Can the European Union admit Ukraine?

- A Roman vision – how integration works

- Dark continent, still

- Colonies and Colonizers

- Candidate status and more – for Ukraine and others

- A moment for leadership

Dear friends,

This is a historic moment for the European project.

On 17 June, the European Commission is likely to propose offering candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova. On 23 June, there will be an EU-Western Balkans leaders’ meeting. On 23-24 June there will be a European Council. The big question at all these meetings will be how to reshape the relationship of the European Union with democracies in Central Europe and in the Balkans, at a time of Russian military aggression and ever more ominous threats coming from Moscow.

Can the European Union admit Ukraine?

Russia’s attack on Ukraine has pushed Finland and Sweden to seek joining NATO. It also prompted Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia to apply for EU accession. Kosovo recently announced that it will apply soon, the last of the Western Balkan states to do so.

These developments raise the prospect of a European Union with 36 or more member states. How will EU leaders respond to these aspirations to join? Some, led by Poland and the Baltic states, have urged the EU since the beginning of the Russian invasion to welcome the Ukrainian application. They warn that denying Ukraine candidate status would send a terrible message to Ukrainians and a dangerous message to Putin, who claims it is his destiny to “return” Ukraine to the Russian sphere of influence.

A second group stresses, that any positive response to Ukraine must not leave earlier applicants from the Western Balkans behind. These countries have been waiting for years to obtain candidate status (Bosnia and Herzegovina) or open talks (Albania, North Macedonia). Why focus only on Ukraine, they ask? What about the others?

A third group of member states urges caution, however. They worry that the EU is too popular for its own good. They warn that it would become dysfunctional by enlarging too much. They suggest that Ukraine, like other applicants in recent years, be offered a vague, conditional perspective.

With the EU divided, the stakes for Ukraine and the EU could not be higher. Meeting the challenges posed by the Ukrainian application requires a strategic vision of Europe’s future. It also requires restoring the credibility of the current accession process.

After all, even to grant Ukraine candidate status, while adding conditions that make the opening of accession talks a distant prospect, would not be good enough. It would repeat the EU’s approach to North Macedonia, which became a candidate in 2005 and then saw its ambition blocked for the last 17 years. As a result, EU-Macedonian relations deteriorated after candidate status was granted. Even opening accession talks might not be enough, if it results in an accession process like that of Turkey (negotiating since 2005), Montenegro (negotiating since 2012) or Serbia (negotiating since 2014), none of whom seem closer to membership today than when they started.

In recent weeks, ESI has argued that there is a way forward that addresses the concerns of all member states. It is to grant candidate status and to open accession talks now, and in addition to offer the following:

All candidate countries that meet the criteria to join the EU, including respect for human rights and the rule of law, should gain full access to the four freedoms – freedom of movement for goods, people, services and capital – and to the European Single Market. Citizens and businesses would then enjoy the same rights as those from EU members or Norway and Iceland enjoy today.

This offer should be made to Ukraine, Moldova and to any Balkan democracy that is interested. It creates an achievable goal. Between 2000 and 2002, it took Lithuania, Latvia and Slovakia 34 months to begin and complete their accession negotiations. It took Poland, Slovenia and Cyprus 56, and Romania and Bulgaria 58 months. Ukraine could be a member of the Single Market, and Ukrainians could enjoy the four freedoms, a few years from now.

Can Ukraine join the European Union? Here is how

30 May 2022

A realist proposal – how the Western Balkans can join the EU

9 May 2022

War and peace in Europe – tragic lessons of recent decades

11 April 2022

Admitting countries that meet the criteria for membership, including the rule of law, to the Single Market does not complicate EU decision making. Joining the Single Market does not first require EU internal reform. Nor does it risk rendering the EU dysfunctional.

The instrument to achieve these ends already exists: it is the current pre-accession process. Every year the European Commission publishes reports on how far each Western Balkan candidate is from meeting EU standards and requirements for the Single Market – from environmental to competition policy – and on the rule of law. It should now do this also for Ukraine and Moldova.

However, once the Commission confirms that a candidate has met these conditions, the Council should offer full access to the Single Market and the four freedoms, and negotiate a treaty similar to the already-existing EU-Western Balkans Transport Community Treaty: a European Economic Community II (EEC), centered around the four freedoms as a framework.

A Roman vision – how integration works

In September 1946, Winston Churchill visited Zurich to “speak about the tragedy of Europe” At a time of civil war in Greece and Stalinist repression in Central Europe, Churchill held out a vision of a different future:

“There is a remedy which … would as if by a miracle transform the whole scene, and would in a few years make all Europe, or the greater part of it, as free and as happy as Switzerland is today. What is this sovereign remedy? It is to recreate the European Family, or as much of it as we can, and to provide it with a structure under which it can dwell in peace, in safety and in freedom.”

In April 2022, Commission president Ursula von der Leyen echoed Churchill in Kyiv:

“we are with you as you dream of Europe. Dear Volodymyr, my message today is clear: Ukraine belongs in the European family. We have heard your request, loud and clear. And today, we are here to give you a first, positive answer.”

Churchill – an opposition politician in 1946 – had a vision that seemed to many like a dream. Von der Leyen, heading the EU’s executive, can offer far more than a dream: a concrete procedure, a process how to join an already existing “structure under which Europe can dwell in peace, in safety and in freedom.”

Turning bold visions into concrete technical steps has been the secret behind European integration. It was realist politicians like Robert Schuman and Konrad Adenauer, inspired by strategists like Jean Monnet, who turned lofty language about a European family into solid institutions.

Rome – where the European Economic Community was born

In March 1957, the leaders of six Western European countries came together to sign the Treaty of Rome that transformed their continent. The leaders meeting announced that they were:

“DECIDED to ensure the economic and social progress of their countries by common action in eliminating the barriers which divide Europe.”

Their goal was political. The means were economic. And their target was the barriers which divide Europe, which were to be removed through the creation of a European Economic Community (EEC).

In Germany, these plans were controversial. Although chancellor Konrad Adenauer obtained the support of the Social Democratic opposition for this project of European integration, some of the leading CDU ministers in his government opposed his plans. It took a strong lead from the chancellor to force his whole cabinet to back his project.

These negotiations also took place at a time of war. While the Treaty of Rome was negotiated, the French military waged the brutal battle of Algiers, torturing and summarily executing prisoners, in what Paris then considered French territory.

War in French Algeria, 1954-1962

But the EEC not only came about; it survived the French empire and the French Fourth Republic, which collapsed one year later. It also survived Franco’s and Salazar’s dictatorships in Spain and Portugal, the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union. It became a magnet for other democracies, which sought to join this unique arrangement.

Nathalie Tocci on candidate status for Ukraine and Moldova

The EEC achieved its success by focusing on eliminating barriers and deepening economic integration. As political scientist Nathalie Tocci put it in Vienna recently, European integration was from the outset a “political project in technical clothing.”

Dark continent, still

In 1990, all European states, the US, Canada and the Soviet Union, met in Paris to celebrate a new era of democratic peace:

“Europe is liberating itself from the legacy of the past … opened a new era of democracy, peace and unity in Europe … steadfast commitment to democracy based on human rights and fundamental freedoms; prosperity through economic liberty and social justice; and equal security for all our countries.” Charter of Paris, 1990

Today, Western Europe resembles the Europe of peace envisaged in the Charter of Paris: a region where armed conflict became unthinkable. Nobody in The Hague makes contingency plans for a potential invasion by France or Germany; nobody in Bucharest and Vilnius envisages armed conflicts with Hungary or Poland.

At the same time, much of post-Cold War Europe remained a continent of war.

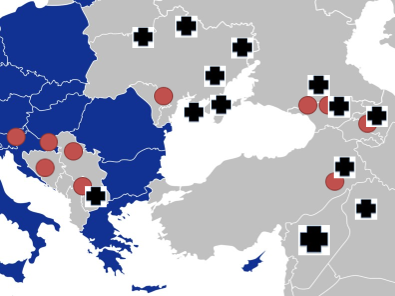

The three decades since 1990 saw 19 wars or armed conflicts in Europe. Only one took place in the old West: the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland, which ended with the 1998 Good Friday/Belfast agreement. All other armed conflicts plagued the development of the Eastern and South-Eastern half of the continent. Many remain unresolved even today.

Stuttgart, May 2022:

War and Peace in post-1990 Europe

![]() Armed conflicts from 1990 to 1999

Armed conflicts from 1990 to 1999![]() Since 2000

Since 2000

Slovenia, 1991

Croatia, 1991-1995 (with ceasefire in between)

Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992-1995

Kosovo, 1998-1999

Serbia, 1999

North Macedonia, 2001

Turkey-PKK, 1990s

Turkey-PKK, 2015-present

South Ossetia, 1991-1992

Transnistria, 1992

Abkhazia, 1992-1993

Armenia-Azerbaijan, 1992-1994

Chechen war, 1994-1996

Chechen war, 1999-2000

Russia-Georgia, 2008

East Ukraine, 2014-present

Armenia-Azerbaijan, 2020

Russia-Ukraine, 2022

In one part of Europe, national borders became more permeable, then invisible. European integration became the world’s most successful project of eliminating barriers. Even democracies which decided not to join the EU were attracted: Iceland, Norway and Switzerland became part of Schengen; Iceland and Norway are also part of the European Single Market. This process unfolded without an imperial centre imposing its control. It was integration among equals, formed around the biggest market in the world.

In other parts of Europe, borders continued to be fought over with blood and bitterness. It is from this tragic cage that Ukrainians are trying to escape.

To succeed, Ukrainians must first fight off Russia. This explains their first priority: to obtain the weapons required to defend their homes.

At the same time, they are finally doing what other newly independent democracies did after the end of the Cold War. On 28 February 2022, four days after the beginning of the Russian invasion, Ukrainian president Zelensky signed an official request for Ukraine to join the EU. On 24 March, Zelensky addressed EU leaders at the European Council meeting, asking all member states to support Ukraine’s membership.

Why did Ukraine pursue EU accession in the middle of a war, while their capital was still under siege? Why did Ukrainian civil servants fill out answers to thousands of questions posed by the European Commission, while battles raged across their country? To understand the urgency, let us look again at what the war is all about.

Colonies and Colonizers

The war against Russia is not only fought to defend Ukrainian homes against an aggressor. It is also fought over radically different visions of the future of Europe.

One vision was offered last week by Russian president Vladimir Putin, when he explained that all countries are either sovereign or colonies:

“In order to claim some kind of leadership – I am not even talking about global leadership, I mean leadership in any area – any country, any people, any ethnic group should ensure their sovereignty. Because there is no in-between, no intermediate state: either a country is sovereign, or it is a colony, no matter what the colonies are called.”

June 2022

Sovereign states can defend themselves. For Putin, this is the case of nuclear powers such as Russia, China, the US and even, as he noted approvingly, North Korea.

Ukraine, so Putin, is not sovereign in this sense. There is no choice for Ukraine to be anything else but part of an Empire. Its destiny is to be conquered and controlled, and the only question is by whom: Russia or the US. Any Ukrainian association with NATO or the EU is therefore seen as a threat, not because it might lead to an attack on a nuclear superpower like Russia, but because it would prevent Russia from asserting its control over its former colony. As Putin warned in the weeks before the war:

“It seems to me that the United States is not so much concerned about the security of Ukraine ... but its main task is to contain Russia’s development. In this sense Ukraine itself is just a tool to reach this goal.”

Colonies are doomed to be tools of great powers, according to Putin. Let Ukraine and other weak European states be Russia’s tool to restore its glory.

This is a view of the past, present and future of Europe that casts the darkest shadow over Ukraine, and over the region between Germany and Russia that the historian Timothy Snyder has called the bloodlands. A region which saw many of the worst crimes and atrocities of the 20th century.

Timothy Snyder in Prague, 2018

Speaking in Prague in 2018, Snyder warned his audience that there was no happy history of nation-states in this region, but a tragic story of foreign occupation and horrific violence. Following the collapse of the traditional land empires of the Habsburgs, Hohenzollern and Romanovs in 1918, new independent states did emerge in Central Europe. However, these states could only maintain their independence for a short period: a few months in the case of Ukraine, Armenia or Georgia, who were reconquered by the Bolsheviks. A few decades in the case of Poland, Czechoslovakia and the Baltic states, who were occupied by the armies of either Hitler or Stalin. As Snyder put it:

“Isn’t it interesting that every single new national state created by the Paris peace settlements of 1918 and thereafter, every single one of them ceases to exist in two decades? Is that simply a coincidence? … Not only do all of these new states formed after 1918 fail, but the entire territory of Eastern Europe governed by these treaties, with exception of Austria, then falls under Soviet domination. Which I would say is a sign not of the success of nation states but rather of continuation of empire now in a different form.”

Official Russia under Putin has long praised the foreign policy successes of its great 20th century Empire-builder, Joseph Stalin, in movies, museums and history textbooks. The narrative of imperial reconquest has also recently inspired Putin to compare himself to Czar Peter I.

In Putin’s eyes there is only one option for Russia’s neighbors: to “return” to the status of vassal states. If they are fortunate, they might end up like today’s Armenia. If they are less fortunate, they might look like the Belarus of Lukashenko. And if they resist imperial control, they will see their cities suffer the fate of Grozny or Mariupol.

Putin and Peter

Putin’s views are terrifying, evoking the darkest periods of Europe’s 20th century. At the same time, the reluctance to let go of colonies and dependencies and vassals is not particularly Russian.

After World War II, many European democracies continued to fight bitter wars to retain control of their Asian colonies: the British in Malaysia, the Dutch in Indonesia, the French in Indochina. They fought “special operations” in Africa, from Algeria to Kenya. They fought anti-colonial movements in Europe, as in the case of British-controlled Cyprus. From the UK to France, from Spain to Portugal, colonial powers did not accept the loss of colonies gracefully. In the end, they learned the hard way that colonialism could not be sustained. They paid a high price to accept this, though a higher price was paid by Vietnamese and Algerians, Kenyans and Angolans. It was defeat on the battlefield– or pyrrhic victories - that liberated European post-war democracies from dangerous illusions. Illusions, which are still dominating the political culture of today’s Russia.

Ukrainians looking West – the Revolution of dignity in 2014

Candidate status and more – for Ukraine and others

There are no good reasons not to grant Ukraine candidate status this June. EU leaders granted candidate status to Turkey 23 years ago in 1999, when Turkey still had the death penalty on its books. They granted it to North Macedonia in 2005. Candidate status does not lead to accelerated accession in either case.

At the same time, opening accession talks with many more countries does pose stark questions to the EU. How prepared is it for another big bang enlargement, for a European Union of 35 or more members? At this moment the honest answer, certainly in Paris and The Hague, Berlin and Copenhagen, would be: not at all.

This is not a debate which the EU will resolve in the next days, though one day it needs to start. However, what can be done now, in response to the Ukrainian and Moldovan applications, is to rethink the current dysfunctional accession process.

If 2022 sees the opening of new accession talks this should be accompanied by negotiations leading also to a European (Economic) Community open to all European democracies, including the Western Balkans. What is needed is a powerful tool to accelerate, in the tradition of Schuman and Monnet, the “elimination of barriers which divide Europe.”

This would be visionary and familiar, as something similar has been done before. This is how Finland, Sweden and Austria joined first the Single Market in 1994 and then the EU in 1995. This was the vision of legendary Commission president Jacques Delors. In his inaugural speech to the European Parliament in January 1989 Delors posed the question how to “reconcile the successful integration of the Twelve without rebuffing those who are just as entitled to call themselves Europeans?” Delors was referring to Austria, Sweden, Norway and Finland. He then offered them a “more structured partnership with common decision-making and administrative institutions.”

Three years later, on 2 May 1992, Austria, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden signed the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement. They became members of the Single Market on 1 January 1994.

This two-step process was no detour. It made EU membership more likely. Veli Sundbäck, the former chief negotiator of Finland, agreed: “For us in Finland, the EEA greatly facilitated our accession negotiations.” As Anders Olander, a former Swedish negotiator, put it:

“For my country Sweden, it was a stepping-stone towards full membership of the EU. Without the EEA Agreement, and the process leading up to it – the best European Integration School that I can think of – we would not have been able to conclude our accession negotiations so easily and rapidly as was the case.”

A moment for leadership

The present moment in European history calls for the practical imagination of a Jacques Delors. Will Ursula von der Leyen pull off something similar?

The present moment requires the bold realism of those who negotiated the Coal and Steel Community and the Treaty of Rome. Can Charles Michel be the Paul-Henri Spaak, Emmanuel Macron the Robert Schuman, and Olaf Scholz the Konrad Adenauer of this generation?

The present moment calls for a vision of Churchillian boldness, which must however be translated into concrete technical steps in the tradition of the Cognac salesman Jean Monnet, who always focused on what Robert Schuman called “concrete achievements which first create a de facto solidarity.”

Of course, Ukraine in 2022 is not Sweden or Austria in 1994. It is a country at war in a continent on edge, at the beginning of a new Cold War. But this makes a robust strategy for future European integration more, not less, urgent.

The attack on Ukraine 24 February 2022 made obvious that the European Union must also prepare to defend its members against the threat of a revanchist Russia. European democracies have achieved security in recent decades through their alliance with the great democracies across the Atlantic, the US above all, but also Canada.

However, if one day European democracies can no longer rely on the US for their security, they must be able to fend on their own to defend their anti-imperial project. They will then want to have as many democracies on their side as possible. A democratic Ukraine that has defied a hostile Russia would be a precious ally.

An ally, not a burden: this is how European leaders should think of Ukraine in the coming days, as they make historic decisions.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

ESI analysis: Offer the four freedoms to the Balkans, Ukraine, and Moldova

ESI videos: New ESI presentations

ESI news on Ukraine:

Philosophy Festival Cologne: “Germany and the war”

Munich – Security conference in Munich

Zurich – Panel on Ukrainian Refugees

Vienna – European Association of Political Consultants: Ukraine and the consequences

Vienna – ERSTE Stiftung: Europe, time to decide

Vienna – Jesuit Community on Europe, War, and Borders

Vienna – BIRN Fellowship for Journalistic Excellence

New Europe Center: A win-win European vision for the EU – Candidate status and four freedoms for Ukraine, 13 June 2022

The European Stability Initiative is being supported by Stiftung Mercator