Accession revolution in Brussels – a new flagship – Usain Bolt and the quality of statistics

- Setting new sails

- Sprinting and statistics – when competition works

- Roadmaps and the benefits of comparison

Dear friends,

It is never easy to turn around a heavy ship in a rough sea and strong wind.

The annual progress reports have long been the flagship of the European Commission's enlargement policy. And yet progress reports have fallen into crisis in recent years, as their prose became incomprehensible and the methodology behind them unfathomable. Their credibility came to resemble the tattered mainsail of a clipper after a devastating storm.

In 2014 a team of civil servants in the directorate general for enlargement of the European Commission (today DG Near) set out to fix the sails and to turn their flagship, the progress reports, around. These efforts gathered speed with the new Commission coming in in summer 2014.

This week on Tuesday the first edition of a new generation of EU accession reports will be published. If developed further in coming years, this may be the beginning of a revolution in accession methodology.

ESI website: A reporting revolution in 2015?

Setting new sails

The EU has never needed a credible enlargement policy more than today. In a number of countries reforms are going into reverse. EU leverage is declining. Bilateral vetoes have proliferated.

Turkey has now been negotiating for ten years. Macedonia has been stuck at the candidate stage for a decade. Bosnia has been told not to submit an application yet. Kosovo has been told that it cannot submit an application, perhaps forever.

In January 2014 Christian Danielsson, the director general of DG Enlargement, invited ESI to present "provocative ideas" on the future of enlargement at the annual "away day" brainstorming of the staff of the directorate. We argued that the most promising way forward was to assess progress so as to allow for meaningful comparisons between countries:

"Enlargement policy needs to mobilise people or it fails. Without the mobilisation of policy makers, civil servants, civil society, and interest groups in accession countries, the kind of changes that have to happen will not happen.

In recent years the technical language of 'chapter openings' has crowded out a focus on what makes accession policy worthwhile and inspiring: More transparent spending whenever public agencies procure goods and services. A credible strategy to ensure safe food. Environmental inspectorates that ensure that dangerous waste is dealt with appropriately. A credible judiciary. Less discrimination of minorities, whether LGBT or religious minorities. Rules for businesses that allow fair competition."

A new generation of annual progress reports should aim at four objectives to stimulate change:

- Fairness: Fair public assessments of where accession countries really stand in terms of meeting EU criteria.

- Strictness: Strict public assessments of where accession countries are failing or falling behind, the more specific, the better.

- Clarity: Clear assessments that can be understood, not just by a handful of experts, but by the broader interested public.

- Comparability: Assessments that encourage comparisons: between the situation in accession countries and EU standards, and among accession countries. Comparisons that encourage friendly competition and mutual learning.

|

|

|

Lars Schmidt, Swedish ambassador to Croatia, Gerald Knaus (ESI), Frank Belfrage, retired Swedish State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Christian Danielsson, Director General DG Near; in Zagreb (2015) |

|

In January 2015 another brainstorming took place in Paris with senior Commission officials, led by the director for strategy, Simon Mordue.

The focus was again on progress reports and how they related to reforms. As an ESI background paper put it:

"For reformers anywhere, time is the scarcest resource. Leaders everywhere face the risk of drowning in information, being swamped by articles, conversations, emails and occasionally reports and books. Active people live on top of ever-growing mountains of words. And a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.

For a report to have an impact it needs to be read. For a report to have an impact on reforms in accession countries it has to be written with a busy and impatient person in mind. Reformers are busy people. If they find time to read quickly, they are also likely to forget quickly. They read and read and read; and forget and forget and forget, like other executives in this age of information surplus."

How then might a report have an impact beyond a few articles on the day after it is published?

"Writing well means, above all else, writing with the potential readers in mind. Let us therefore imagine an accession country with only five inhabitants, as follows:

- A 'Big boss' – a prime minister, president …

- A 'Little boss' – a regional leader

- 'Appleby' – a senior and influential civil servant

- 'Businesswoman' – a producer and potential exporter

- 'Citizen' – an average voter

We can expand this model: add a journalist (who writes for the most read daily paper), an opposition leader (who itches to publicly challenge big boss) and minister of X (who might conclude that doing well in areas under her responsibility is a good way to gain a political profile).

But any impact in the end depends on the report actually being read; understood; its core messages remembered; its analysis found to be fair. Only then will it change how Big Boss, Little Boss, Appelby act and Businesswoman and Citizen think. And without this, it might as well not be written."

ESI Paris paper: Enlargement and Impact: Twelve ideas (January 2015)

ESI presentation: Assessment – Competition and reform (January 2015)

Enlargement 2.0 – The ESI Roadmap Proposal (Belgrade) (November 2014)

Sprinting and statistics – when competition works

When it comes to running fast, it is essential not to do so all by yourself. As John Brenkus writes in "The Perfection Point" about the 100 meter sprint:

"Without direct and visible competition, times would be far slower. Send [Usaine] Bolt down a track solo and he wouldn't have a prayer of coming anywhere close to a record time. As a matter of fact, he wouldn't even have a respectable time.

At those speeds, there's simply no way to gauge how fast you're going other than in comparison to what your competitors are doing. It's why the center lanes are so coveted and are always assigned to those with the fastest preliminary heats. They give the athlete the best view of as many of the other runners as possible."

This is a normal human tendency, a secret of performance in many fields: it helps to look to others for inspiration and incentive. It is also true for reformers: to be able to look to those engaged in a similar endeavour, from a centre lane, in a spirit of friendly competition, offers a huge advantage. But can this insight also be applied to the adoption of EU rules at the heart of the accession process?

We set out to explore this question in different fields.

One was anti-corruption, where we recommend learning from the experience of the EU's owns Anti-Corruption Report (2014) in our paper Measuring corruption – The case for deep analysis and a simple proposal (19 March 2015). A second was statistics (Chapter 18).

Statistics are essential in the process of European integration: the European Union is a union based on trust in numbers. In fact, the success of any modern society is linked to its mastery of national accounting. Trustworthy statistics are a foundation for evidence-based policy making. They make those who govern accountable to citizens. They help leaders see gathering storm clouds. When national accounting fails – as became clear in Greece in 2009 – societies can collapse into deep crises.

At a seminar in Stockholm in October 2014 we explored how previous progress reports had handled statistics. What we found was disturbing. There were only four short paragraphs per country in each progress report. Sometimes these paragraphs did not change at all from year to year. Nothing allowed for any comparison in the quality of statistics between accession countries. Each country was assessed using different criteria. Nor was it possible to assess progress over time.

Progress Reports on Chapter 18 – Turkey

Conclusions

|

2013 Progress has been made in the area of statistics, with the submission of an agriculture statistics strategy and the revision of tourism statistics. Further progress is needed on national accounts, agriculture statistics and regional statistics. Cooperation between TurkStat and main data providers needs to be strengthened. Alignment with the acquis is at an advanced level. |

2014 There has been progress on statistics, with the revision of producer price indices and quarterly national accounts. Further work is needed on national accounts, agriculture statistics, regional statistics, and to strengthen the cooperation between TurkStat and main data providers. Overall, the level of alignment with the acquis is advanced. |

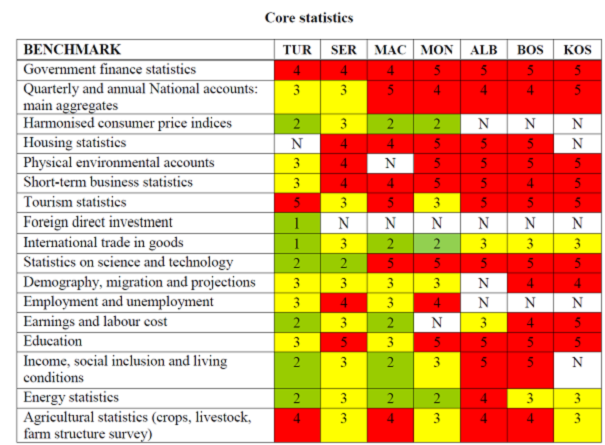

Then we discovered that Eurostat does in fact annually assess the quality of statistics in all seven accession candidates. It also grades compliance with European standards. The problem, it turned out, was not a lack of assessments but a lack of transparency.

These detailed Eurostat assessments remained secret. They were not shared either with the public or even with international donors.

This means losing out on a huge opportunity. When ESI obtained the seven country reports we translated Eurostat's five grades into the colours of a traffic light:

Eurostat statistics grading scale

"Fully compliant – requirements fully observed with respect to all criteria": grade 1 – green

"Highly compliant – minor shortcomings, large majority of criteria fully met": grade 2 – green

"Medium compliant, important shortcomings, substantive actions to be taken": grade 3 – yellow

"Low compliant, major shortcomings, a large majority of criteria not being met": grade 4 – red

"Not at all compliant, requirements are not observed at all": grade 5 – red

"Not set means that modules or datasets are not assessed/evaluated" (below N)

It became possible to compare the quality of sectorial statistics between countries; to see visually where more focus is needed:

ESI Statistics Scorecard – how to compare 7 countries (May 2015)

ESI table: 2014 sectorial statistics readiness ranking

|

Country |

Number of benchmarks assessed |

Average |

|

Turkey |

42 |

2.7 |

|

Serbia |

42 |

3.2 |

|

Macedonia |

40 |

3.4 |

|

Montenegro |

38 |

3.9 |

|

Albania |

39 |

4.0 |

|

Bosnia |

35 |

4.1 |

|

Kosovo |

33 |

4.3 |

Roadmaps and the benefits of comparison

It has been possible to draw up roadmaps for specific reforms needed for visa liberalisation; then DG Home was able to grade them on a scale of 1-5. See here Turkey's visa liberalisation scorecard (December 2014).

It has been possible to do the same for the quality of crucial statistics essential for any economic governance; then Eurostat was able to grade them on a scale of 1-5.

It should be possible, we now argued in meeting after meeting, to do something similar in other policy fields, beginning with procurement and financial control. To produce a similar effect on reformers as the OECD Pisa studies produced in the field of education. To use comparisons to stimulate mutual learning and competition. To allow reformers to run in the centre lane, able to look to others for inspiration and incentives. And for the interested public to understand where their countries really are in terms of the substance of accession.

This week a new generation of reports will be presented in Brussels; if these are the principles that they will embrace – fair comparisons, meaningful competition and transparency of criteria – then the practice of enlargement policy would be transformed, with potentially profound positive effects for one of Europe's most sensitive regions.

Yours sincerely,

Gerald Knaus

- NEW: A reporting revolution in 2015? Towards a new generation of reports

- NEW: Paris paper: Enlargement and Impact: Twelve ideas - Jan 2015

- NEW: Statistics Scorecard – how to compare 7 countries (May 2015)

- NEW: An effort of persuasion – Chronology of ESI activities (November 2015)

- NEW: Rankings that fail – Bosnia, Macedonia and Doing Business 2015 (9 November 2015)

- Measuring corruption – The case for deep analysis and a simple proposal (19 March 2015)

- ESI report: Vladimir and Estragon in Skopje – A fictional conversation on trust and standards and a plea on how to break a vicious circle (17 July 2014)

- PRESENTATIONS:

- Video: Enlargement and the benefits of competition (26 February 2014)

- Enlargement reloaded – ESI proposal for a new generation of progress reports (31 January 2014)

- Motivation, competition and the future of Progress Reports (Paris 2014)