Winter is coming – Polish Bulldozer – win-win-win for the rule of law

- Winter is coming

- Episode I – bullying the ECJ

- Episode II – bullying the Supreme Court

- Episode III – Bullying judges

- Episode IV – Firing all referees (again)

- Episode V – The Council of Europe is irrelevant, too

- A win-win-win for Poland and the EU

- The end of the road – midwinter spring

Dear friends of ESI,

Please find attached the latest ESI report on Poland and the rule of law:

The Polish Bulldozer

Towards a win-win-win for Poland, the EU and

the European Commission

18 December 2021

Our report describes dramatic developments in Poland in 2021. It also suggests a way forward, how to protect the rule of law and how to resolve the EU’s deep crisis this winter, in three steps:

1. For the European Commission to preserve the independence of Polish courts it must urgently send a letter to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and ask the ECJ a) to declare that Poland has failed to fulfil its obligations under EU law and b) to impose a penalty payment. Time is running out to pre-empt further drastic changes damaging the Polish judiciary.

2. The suggested financial penalty must be high enough to ensure that Poland will fully implement the historic 15 July 2021 ECJ judgement on its disciplinary system. The Commission’s guidelines on penalty payments refer to “the need to ensure that the penalty itself is a deterrent to further infringements.” ESI proposes 1 percent of Polish GDP per year, which is around 5 billion Euro.

How infringement penalties are set – the case for 5 billion

5 August 2021

3. The European Commission should also explicitly link disbursements from its new Resilience and Recovery Facility (RRF) to the implementation of ECJ judgements on the rule of law.

ECFR Debate video: Does Poland have a point?

Winter is coming

Time is not on the side of the rule of law in Poland. After a year full of dramatic events in the battle over the independence of its courts between the European Commission in Brussels, the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg and the Polish government, the leading hardliner in Warsaw, justice minister Zbigniew Ziobro, is convinced that he is winning. He has taken off his gloves and cast all restraint overboard.

Five episodes from Poland 2021 show how.

European Court of Justice (ECJ) – Zbigniew Ziobro

Episode I – bullying the ECJ

“Yielding to the European Union, yielding to foreign pressure, yielding to threats and unlawful demands leads to legal chaos in Poland and is a road to nowhere.”

Zbigniew Ziobro, 23 July 2021

On 15 July 2021 the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in Luxembourg issued a historic judgement. It warned that any disciplinary regime for judges “must provide the necessary guarantees in order to prevent any risk of being used as a system of political control of the content of judicial decisions.” It concluded that a new disciplinary regime for judges had created a situation where Polish judges had good reason to fear consequences for themselves if they issued rulings not to the liking of the minister of justice, who is also Poland’s prosecutor general: Ziobro.

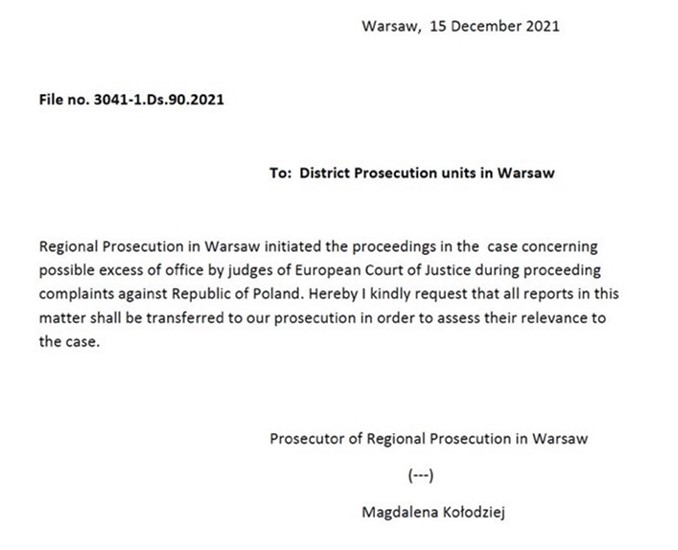

The reaction by Ziobro to this judgement was typical: first outrage, then hostile indifference, and finally threats and intimidation: this weekend his prosecutors launched a criminal investigation against ECJ judges in Luxembourg, demonstrating once again his approach to judges he does not control.

Letter by Warsaw Regional Prosecution – translation arranged by Wolnesady

Episode II – bullying the Supreme Court

In 2007, when Ziobro was minister of justice for the first time, Małgorzata Manowska was his deputy. In 2016, after Ziobro became minister again, he appointed Manowska as director of the National School of Judges. In May 2020, she became president of the Polish Supreme Court.

In April 2020, the ECJ issued an order suspending some activities of a new disciplinary chamber of the Supreme court. The Supreme Court president at the time issued an order to comply. In July 2021, the ECJ issued an order suspending all activities of the disciplinary chamber.

As president of the Supreme Court Manowska faced a choice. She could comply with the order. However, a few hours after the ECJ order, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal ruled that such ECJ orders were unconstitutional. Ziobro celebrated this as a big success.

On 16 July, Manowska made her choice. She declared that she agreed with Ziobro and would follow the Constitutional Tribunal: “European law does not cover the field of the organisation of justice.” She allowed the Disciplinary Chamber to operate without restrictions. Ziobro praised her publicly.

Then, on 20 July, the European Commission announced that it would seek financial penalties against Poland over this. Two days later Manowska stated that she was considering suspending the operation of the disciplinary chamber again. On 28 July, Manowska wrote to the government, suggesting that Polish laws should be brought in conformity with European law. She referred to “possible far-reaching financial consequences for Poland of failing to implement the ECJ rulings.” On 5 August, Manowska issued new orders suspending the work of the disciplinary chamber. She referred to “the need to respect international law binding on the Republic of Poland.”

So what was legal? What constitutional? Confusion deepened. On 9 August, Manowska stated again that, in fact, she agreed with the Polish Constitutional Tribunal and not with the ECJ.

At the same time, she did not rescind her order freezing the operations of the disciplinary chamber. But was this not unconstitutional? Manowska explained that the point of her order was “to give time to politicians … So that the threat of financial penalties does not hang over their heads.”

Supreme Court president Malgorzata Manowska

and minister Ziobro

Ziobro was outraged over Manowska’s U-turns. As he put it, she had justifed “Poland’s full capitulation to the illegal demands of Brussels.” This was indefensible: “I look at it sadly. You cannot defend it and pretend that such behavior adds seriousness to the Supreme Court.” Ziobro concluded that Manowska was not up to her job:

“A person who has decided to perform the responsible function of First President of the Supreme Court should be resistant to threats and pressure, both from foreign institutions and from the politicized part of the judiciary and the media supporting her. The decisions made by Mrs. Manowska mean that unfortunately she was not able to meet this challenge.”

Ziobro was clear what should happen: “In connection with the orders issued yesterday by the First President of the Supreme Court, Małgorzata Manowska, blocking the full work of the Disciplinary Chamber, I declare as minister of justice that these are actions contrary to Polish law.” And this is what happened.

The disciplinary chamber kept working. It suspended more judges. On 16 November, it suspended judge Maciej Ferek from the Kraków Regional Court. On 24 November, it suspended judge Piotr Gąciarek from the Warsaw Regional Court. On 15 December, it suspended judge Maciej Rutkiewicz from Elbląg District Court. Manowska was ignored. The ECJ order was ignored.

As Ziobro bullied and pushed around judges, including those he once favoured, chaos descended upon the Supreme Court. Meanwhile Ziobro contemplated how to get rid of the judges who do not do what he wants.

Ziobro’s target: judge Beata Morawiec

Episode III – Bullying judges

The 15 July 2021 ECJ judgement had warned that a newly created disciplinary chamber in the Polish Supreme Court “did not provide all the guarantees of impartiality and independence and, in particular, is not protected from the direct or indirect influence of the Polish legislature and executive.”

This new chamber of 12 judges decides on disciplinary cases and on lifting the immunity of judges in case of criminal investigations by Ziobro’s prosecutors.

In February 2020, prosecutors requested the waiver of judge Ivan Tuleya’s immunity. Tuleya, a critic of Ziobro, was accused of abuse of power for allowing media to be present in a trial concerning the ruling party. In June 2020, a single judge in the disciplinary chamber refused to lift his immunity. Prosecutors appealed. In November 2020, a three-member panel in the disciplinary chamber lifted Tuleya’s immunity. He was suspended. Ziobro was pleased.

Inside the system Ziobro built

5 August 2021

Compare this to the case of judge Beata Morawiec. In 2017 Ziobro fired her, without justification, as president of the District Court in Kraków. He had gained the right to fire and appoint all court presidents in Poland, which he is using extensively.

Prosecutors then started an investigation against her, asking the disciplinary chamber to lift her immunity. In 2020, in a one-hour hearing held behind closed doors, one judge of the chamber accepted the prosecutors’ request and ruled that Morawiec’s immunity should be lifted. He suspended her from official duties and cut her salary by half. In July 2021, a panel of three at the same chamber decided with two to one votes not to lift her immunity.

Ziobro called a press conference. Furious, he charged that the two judges whom he singled out had “shamelessly [put] the unworthy corporate interest of the judicial community above the law.” Their decision was not just wrong, the minister explained, it was evil: “The judicial community is incapable of self-cleaning. It is not capable of decisively fighting the evil and pathologies within its own environment.”

This left him with a dilemma: how to ensure that there are no more cases where judges disobey Ziobro’s prosecutors? His solution became clear very quickly.

Episode IV – Firing all referees (again)

“The most extreme way to capture the referees is to raze the courts altogether and create new ones.”

How Democracies Die, Levitsky and Ziblatt

As Ziobro became dissatisfied with both the disciplinary chamber and the unreliable behaviour of the Supreme Court president in 2021 he began to propose new ways to get rid of both. Not to increase their independence, as the ECJ demanded, but to gain more control over judges.

As Ziobro put it on 5 August: “Under no circumstances should one succumb to the unlawful and aggressive actions of the ECJ and of the European Union.” Polish politicians had already tried that in 2017 with awful results:

“it is clear that the policy of concessions to successive demands from Brussels [in 2017] … has not been effective in recent years. If we had done our part and not given in and withdrawn the planned changes, the reform of the judiciary would have been completed long ago.”

Here Ziobro was referring to a July 2017 law that would have sharply reduced the Supreme Court’s competencies, vetted all its judges and its staff, decreased the number of its judges to 44 and moved the Court under the firm control of his ministry.

His new strategy is thus his old one, to go back to the laws he proposed to parliament in 2017, which were then not signed by the president: to vet all Supreme Court judges and staff, to fire most of them, to dramatically weaken the Supreme Court, to replace all existing chambers and in addition to reappoint all judges throughout Poland (!), as all ordinary courts are to be reorganised as well.

For months now Ziobro has blamed weak Polish politicians for not pushing through his bulldozer reforms (as his deputy minister recently referred to them). On 15 November, Ziobro announced that new drafts “were sent (to the government) for consultation two months ago.” Two weeks later, he added: “I propose that we … break with the policy of stubbornly trying to pander to EU institutions.”

The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg

Episode V – The Council of Europe is irrelevant, too

Poland is not only a member of the European Union, but also of the Council of Europe. This means that there is a second European Court – the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in Strasbourg – responsible to defend the human rights of Polish citizens that derive from the European Convention on Human Rights.

However, the Polish government and the Constitutional Tribunal not only claim today that they can ignore judgements by the EU’s highest court, the ECJ in Luxembourg; they claim the same for the Council of Europe’s highest court, the ECtHR in Strasbourg. As Oliver Garner and Rick Lawson wrote recently in Verfassungsblog:

“the ruling party’s problems are not limited to the European Commission or even the European Union. Poland is also at loggerheads with the Venice Commission, GRECO, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) and, come to think of it, more or less any international supervisory body that has reviewed the situation of the rule of law in Poland recently.”

On 7 May 2021, the ECtHR ruled that the Polish Constitutional Tribunal is not a “tribunal established by law.” It based this on the illegal methods used by the Polish government in 2015 and 2016 to take control of this tribunal.

On 22 July 2021, the ECtHR ruled that the disciplinary chamber of the Supreme Court is not a “tribunal established by law.”

These judgements were rejected by the Polish government, claiming that article 6 of the ECHR did not apply. This article states that “everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.”

On 24 November 2021 the Polish Constitutional Tribunal ruled that this requirement did not apply to itself. It certainly does not at this moment.

A win-win-win for Poland and the EU

Guardians of the treaty: Ursula Von der Leyen, Vera Jourova, Didier Reynders

Commission president, vice-president, and Commissioner for Justice

In 2017, the Commission announced that it would prioritize all ECJ cases that undermine the rule of law. Now is the moment to do so. When member states ignore ECJ judgements the Commission’s guidelines provide for the possibility of exceptional fines “where appropriate in particular cases … to ensure effective application of Community law.” This includes “the need to ensure that the penalty itself is a deterrent to further infringements.”

This certainly applies to the 15 July 2021 ECJ judgement on the disciplinary system, which found that the right to “effective legal protection” was seriously undermined. There has never been an ECJ case that posed a greater threat to the EU legal system. The Commission should therefore propose an exceptionally large fine, based on an Article 19 – European Free courts principle:

Article 19 principle for European free courts

Whenever the ECJ finds that the right to “effective legal protection” through national courts, which Article 19 of the EU treaty guarantees, is violated by member states, and these do not remedy the situation, a financial sanction shall be imposed that is at least 1 percent of the GDP of the country annually.

In the case of Poland, which has a GDP of about € 520 billion, this would amount to a fine of some € 5.2 billion annually. The Commission should therefore propose, and the ECJ should impose a fine of € 880 million every two months until the Polish government implements the 15 July 2021 ruling.

The end of the road – midwinter spring

In recent months, Ziobro has taken off his gloves. He no longer pretends to care about European law and courts.

It is time for European institutions to prove that European law and institutions are stronger than the chaos that he has already brought to his country’s courts. But time is running out. The longer the Commission waits, the bigger the chances are that even more damage will be done to the Polish judiciary. Winter has come to Poland.

As guardian of the treaty, the Commission has an obligation to act. It also stands a very good chance of success. Ziobro’s political masterstroke has been to get as far as he has while pursuing an agenda that most of his compatriots do not share. Surveys show that Ziobro’s agenda is far from popular.

The time to take Poland back to the ECJ is now. For this the European Commission must only send off one more letter. The European Commission should put a clear choice before pro-EU Polish conservatives, without whom Ziobro cannot maintain his control: a choice between his radical agenda on the one hand and billions of Euros supporting Poland’s development on the other. By calling Ziobro’s bluff the European Commission and the ECJ not only save the rule of law in Poland and in the EU, but also break his spell over a shrinking radical minority.

This would be a win-win-win scenario: A win for the rule of law in Poland. A win for the European legal order. A win for the people of Poland, as EU funding is disbursed. A win also for pro-EU Polish conservatives, fed up with Ziobro’s bulldozer tactics and concerned about his extraordinary power over courts.

It would be a historic achievement for the European Commission and the ECJ: a midwinter spring for Europe.

Best wishes,

Gerald Knaus

Twitter: @rumeliobserver

Can the European Commission react in time before more damage is done to Polish – and EU – rule of law? Yes, it can.

Here is what needs to be included in the letter it needs to send to the ECJ (from a court case involving Ireland in 2020):

“The European Commission requests from the ECJ to:

– declare that, by having failed to adopt by … at the latest, …. or, in any event, by having failed to notify those provisions to the Commission, Poland has failed to fulfil its obligations under …;

– impose a periodic penalty payment on Poland pursuant to Article 260(3) TFEU in the amount of EUR …, with effect from the date of the judgment of the Court, for failure to fulfil its obligation to notify the measures …;

– impose the payment of a lump sum on Poland pursuant to Article 260(3) TFEU, based on a daily amount of EUR … multiplied by the number of days of continued infringement, with a minimum lump sum of EUR …, and

– order Poland to pay the costs.”

www.esiweb.org/proposals/how-rule-law-dies-poland

The Polish Bulldozer

Towards a win-win-win for Poland, the EU and the European Commission

18 December 2021

5 billion to save the EU – Poland, Penguins and the Rule of Law

6 August 2021

Also available in French, German, and Polish

Inside the system Ziobro built

5 August 2021

Ziobro and Commissioner Reynders in Warsaw, 18 November 2021

An Article 19 Mechanism to save the rule of law in the EU (5 August 2020)

Beyond the silent cash-machine – smart solidarity (27 April 2020)

How the rule of law dies … is this possible inside the EU? (16 December 2019)

Poland’s deepening crisis – When the rule of law dies in Europe (14 December 2019)

Tolstoy, Causes, Poland and the Aegean (15 April 2019)

Najbardziej niezbezpieczny polityk w Polsce – spuścizna Junkera (4 April 2019)

Under Siege – Why Polish courts matter for Europe (22 March 2019)

The disciplinary system for judges in Poland – The case for infringement proceedings (22 March 2019)

Where the law ends. The collapse of the rule of law in Poland – and what to do (29 May 2018)

Poland’s most dangerous politician – Juncker's legacy (27 March 2019)

Win-Win for Europe: Defending democracy in the Balkans – and in Poland (22 June 2018)

European tragedy – the collapse of Poland’s Rule of law (29 May 2018)

Der Spiegel, Poland’s Judges Are Fighting To Save Rule of Law and Their Own Jobs (13 August 2021)

Der Spiegel, Gefährdete Rechtsstaatlichkeit – Kämpft um Polen! (24 July 2021)

Budapester Zeitung, Ein Rechtsstaatmechanismus, den man nicht politisieren kann (1 August 2020)

Der Spiegel, Demokratieverfall in Ungarn und Polen – Wie die EU die Autokraten doch noch zügeln könnte (25 July 2020)