Sunday conversation in Saint Germain-en-Laye

The man emerging from the metro in Saint Germain-en-Laye on this cold Sunday afternoon in February is ebullient, unbowed and confident about the future of his country. This is remarkable, for my visitor is the political activist and writer Emin Milli, who had just emerged (again) from prison; the country in question is Azerbaijan.

Our paths first crossed when ESI worked on and then published in March 2011 a report about him, his friend Adnan and other members of Generation Facebook in Baku. The report described the emergence of a new generation of dissidents in Azerbaijan, and the strategy of repression used by the regime.

Emin Milli, a blogger, writer, activist and former political prisoner protesting

against violence against conscripts in the Azerbaijani military in Baku, 12 January 2013

Since Generation Facebook we have been in touch regularly. In January this year we met in Budapest during a seminar discussing the future of election observation missions in Europe. We then spent a day in Rumeli Hisari in Istanbul, discussing how the Council of Europe might help set free political prisoners across Europe. For Emin this is also a personal issue. He had spent 16 months in jail in 2009 and 2010. Our discussion was in the shadow of a forthcoming vote we were both watching carefully.

Emin Milli in Rumeli Hisari, Istanbul, January 2013. A few days later he will again be arrested after peacefully demonstrating against police violence.

Emin Milli in Rumeli Hisari, Istanbul, January 2013. A few days later he will again be arrested after peacefully demonstrating against police violence.

A few days later a resolution on political prisoners in Azerbaijan was rejected by a clear majority in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). This was a historic debate – the best attended ever! – which saw remarkable and outrageous statements from European parliamentarians attacking the rapporteur and his work and defending the regime of Ilham Aliyev.

I ask Emin how he felt when he heard about the outcome of this debate on his country. He notes:

“When I heard about the vote against the resolution what came to my mind, strangely, was the fall of the Roman Empire. I thought: it is amazing how one small authoritarian regime can bring the proud tradition of democracy in Europe down in the Council of Europe.”

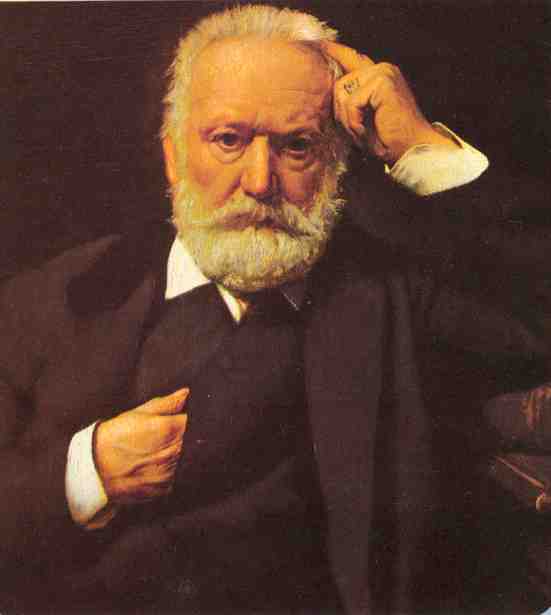

Three days after this vote Emin was arrested again following peaceful demonstrations. He spent two weeks in jail, together with others who had taken part in the demonstration. Emin tells my young daughters that prison offers a lot of time to read and that it helps to lose weight. Emin also explains that this time in prison he reread Les Miserables, one of the great novels of the 19th century. I tell him that Victor Hugo once lived near Saint Germain-en-Laye in the West of Paris, where we are now. Hugo was a visionary himself. He did, after all, tell the 1849 (!) Peace Congress in Paris:

“A day will come when the only fields of battle will be markets opening up to trade and minds opening up to ideas. A day will come when the bullets and the bombs will be replaced by votes, by the universal suffrage of the peoples, by the venerable arbitration of a great sovereign senate which will be to Europe what this parliament is to England, what this diet is to Germany, what this legislative assembly is to France. A day will come when we will display cannons in museums just as we display instruments of torture today, and are amazed that such things could ever have been possible.”

Compared to this vision, is the idea of the Southern Caucasus one day joined together with the rest of democratic Europe any less realistic? Is it less realistic than imagining in 1983 Poland joining the European project or in 1993 Croatia being a part of it? Hugo spoke those words before the Paris Commune, the two World Wars and the Cold War. He spoke them as an optimist – but given the European Union of today a farsighted rather than foolish one. I am certain that Hugo would have liked the vision and determination of Emin’s generation in Baku. As Hugo put it at the end of Les Miserables:

“… a progress from evil to good, from injustice to justice, from falsehood to truth, from night to day, from appetite to conscience, from corruption to life; from bestiality to duty, from hell to heaven, from nothingness to God. The starting point: matter, destination: the soul. The hydra at the beginning, the angel at the end.”

The hope for peaceful change

What is the hydra in Azerbaijan today? It is the authoritarian and oligarchic regime of president Ilham Aliyev. Is there an Angel? It must be the hope of a peaceful transition to democracy.

We sit down and Emin begins to explain:

“Before I did not see a chance for a democratic, non-violent and managed transition, as opposed to violent, anarchic and chaotic change. Now I can see a chance for this, even this year.”

Emin arrested again, following peaceful protests against police violence on 26 January 2013

The key for any breakthrough is for new and traditional opposition groups to come together around a common platform, program of change and a common candidate in upcoming presidential elections.

“There are of course the old opposition parties like Musavat and the Popular Front, but they are no longer alone. There are also now intellectuals who defected from the regime and who are popular in Azerbaijan, members of the new Intelligentsia Forum: scientists like Rufiq Aliyev, who is a candidate for a Nobel Prize, or film makers like Rustam Ibrahimbegov, who won an Oscar. They have now broken with Aliyev. There are many Western educated young people who have returned, like Harvard-educated former political prisoner Bakhtiyar Hajiyev. There are other opposition parties with serious programs, such as the Republican Alternative of Ilgar Mammedov or Erkin Gadirli. There are the young activists of the facebook generation.

In the past it was easier for the regime to discredit the opposition, but this would be hard in the face of a common opposition front. This is a very different scene from the one we had before elections in 2010, 2008 or 2005.”

But will there be a joint platform for elections in 2013?

“Different political groups and social forces seem to realize now that coming up with a united political platform for change may be the key game changer in Azerbaijan this year. This would mean having one joint presidential candidate and a joint political platform with a clear agenda for a transition government, which would lead Azerbaijan from a presidential monarchy to a parliamentary republic.“

Emin’s cautious optimism is also based on the new media revolution in Azerbaijan. He sees many concrete signs of the impact of this ongoing revolution:

“Opposition newspaper Azadliq sold 200,000 hard copies during the national independence movement in the late 80s. It went down to selling just 10,000 copies. This year in January 2013 some news put on the website of Azadliq were read by more than 200,000 people. So there is a bigger public sphere, which has expanded enormously.”

“The reason I am optimistic is the monopoly of information once held by the government in Baku is corroding, even beginning to crack. First, you see this on YouTube, as countless of videos capturing violence and abuse of power circulate. The Internet has lowered the barriers to entry

“Furthermore, the rise in satellite TV broadcast from Turkey are spreading these videos. These YouTube clips expose the regime as a criminal gang. They show threats, blackmail, the open selling of parliamentary seats … and how even members of the elite treat each other.”

(For more on new media in Azerbaijan read also this recent article)

“Hundreds of thousands now watch Youtube videos. These include the shocking videos put online by the former rector of Baku university Elshad Abdullayev in conversation with various important members of the regime. Elshad Abdullayev taped many of his conversations over many years; having fled Azerbaijan he is now putting them online. These tapes have exposed just how corrupt and criminal the regime is. People knew this, but these videos made the truth obvious, and create a lot of silently rising anger and outrage: they see members of parliament selling seats for more than a million Euro. Hundreds of thousands also watch them broadcast from Turkey on satellite TV.”

“These clips expose the regime as a criminal gang. They show threats, blackmail, the open selling of parliamentary seats … and how members of the elite treat each other.”

(to see one of these videos with English subtitles go here)

“There is also a growing sense of disenchantment with the regime all over the country. Various social groups shop-keepers, relatives of people serving in the military, local people in different provinces of the country – have started to protest in numbers and ways not seen before within one month. In January 2013 I saw groups I had never imagined would go on the streets to protest. Shopkeepers closed a road and protested against the owner of one of the biggest shopping malls in Azerbaijan who wanted them to pay more rent. Then there were the protests on 12 January against violence against conscripts in the military.”

At the same time there are signs of a potentially dangerous escalation in the regions. Riots in the Ismayilli region in January 2013 showed how quickly things can escalate now. They were, Emin explains,

“a repeat of protests in another region, Guba, last year. There local people were so frustrated with their living conditions that they did not see any other means to communicate their frustration than violence. In Guba in 2012 they burned down the house of the governor, who was then fired by the president. In Ismayili the hotel and part of the governor’s house were again burned down.”

There is a possibility of such protests spreading:

“People protested and burned the house of governor in Guba, then he was fired. People in Ismayilli burned hotel and house of the governor, then he was fired too. What sort of message does this send to people in other regions? The only way the government respects the people is when houses burn? This is no way to govern the country. Firing a couple of governors will not solve the problem of feudal style governance in the regions either. People want to be heard.”

“These protests are out of control of the opposition, which is not even allowed to go to the regions.”

The Aliyev regime is clearly nervous about all this:

“For the first time in a very long period the regime moved troops into regions of Azerbaijan. The pictures of the stand-off reminded people of the days when in 1990 Soviet troops entered Baku. Now again hundreds of people were detained, arrested, tortured. And in spite of this very violent reaction of the state it did not stop any of the following protest actions.”

The president has also appeared unnerved:

“The first reaction was that the governor will stay, that these were just some local hooligans. Then a couple of weeks later Ilham Aliyev goes on television and threatens governors and ministers that their sons will be put in jail if they misbehave, that if they curse or insult people they will be jailed and their fathers will be fired.”

At the same time the regime is clamping down hard in light of the upcoming presidential elections in October 2013:

“For the first time in recent Azerbaijani history a presidential candidate was put in jail during an election year! This is a different level of nervousness than before. Ilgar Mammedov from the Republican Alternative opposition party is a presidential candidate. He went to Ismayilli and was jailed, accused of inciting events. This is absurd: he went there after everything was over. Isa Gambar, another presidential candidate, was prevented by a mob and police from entering Lankaran in the South of the country. Ali Kerimli, another potential presidential candidate and opposition leader does not have a passport for seven years now, and he also does not have an office.”

“The government has tried to close more political space. It started clamping down on the opposition. This explains this rise of unorganized, sometimes violent, unpredictable revolts. If these developments are ignored by the international community we might end up with situations similar to those in the Arab world.”

Emin sees an opening for a different kind of opposition under conditions of general dissatisfaction, leading to a gradual transition:

“This is the moment for opposition groups and leaders to come together in a united front, to direct frustration and outrage of the population in a responsible way. The opposition must unite and organize the transition to a parliamentary republic. The problem in 2003 was that the opposition was split. It was not united, not on the street, and not politically. Until now it has never united.”

“A united opposition sharing resources, sharing energy, with a message of unity, thus giving real hope to people could be a historic moment in our country. This means presidential elections this year in October might be very interesting. There are symptoms of real change in the air. It all depends now on how internal and external actors behave in this situation.”

Of course, much can go wrong and even more would have to go right for any of these optimistic scenarios to come about. There still is no united opposition. There is always the potential for further repression. So far there have never been free and fair elections in Azerbaijan, so it is unrealistic to expect 2013 to be different. There are likely to be further arrests. Standing up for democracy and human rights in Baku is a high risk strategy still, and any rewards are highly uncertain.

All of this makes it even more important what messages outside institutions are prepared to send. So I ask Emin: how does he see the role of external actors? Will they care? Will democratic Europe, will European institutions, do what they can to support a peaceful evolution, based on respect for human rights in Azerbaijan?

“The situation in Azerbaijan may change rapidly. The international community must sternly warn the government that any violent suppression of peaceful democratic change will not be accepted. The challenge is to prevent another Egypt, another Libya. The challenge is to have a peaceful transition like in Central Europe in 1989. We need a scenario in Azerbaijan like the one in Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980s.”

As I see Emin off, next to the former royal castle of Saint Germain-en-Laye, I think again of Victor Hugo, and his universal concern for the rights of the oppressed. As Hugo put it in a letter to a publisher of Les Miserables:

“It addresses England as well as Spain, Italy as well as France, Germany as well as Ireland, the republics that harbour slaves as well as empires that have serfs. Social problems go beyond frontiers. Humankind’s wounds, those huge sores that litter the world, do not stop at the blue and red lines drawn on maps”.

This remains as true today as it was in the 19th century.

Viktor Hugo, writer, author of Les Miserables and visionary who wrote the Opening Address

Viktor Hugo, writer, author of Les Miserables and visionary who wrote the Opening Address

to the August 1849 Peace Congress in Pariscalling for a European federation.