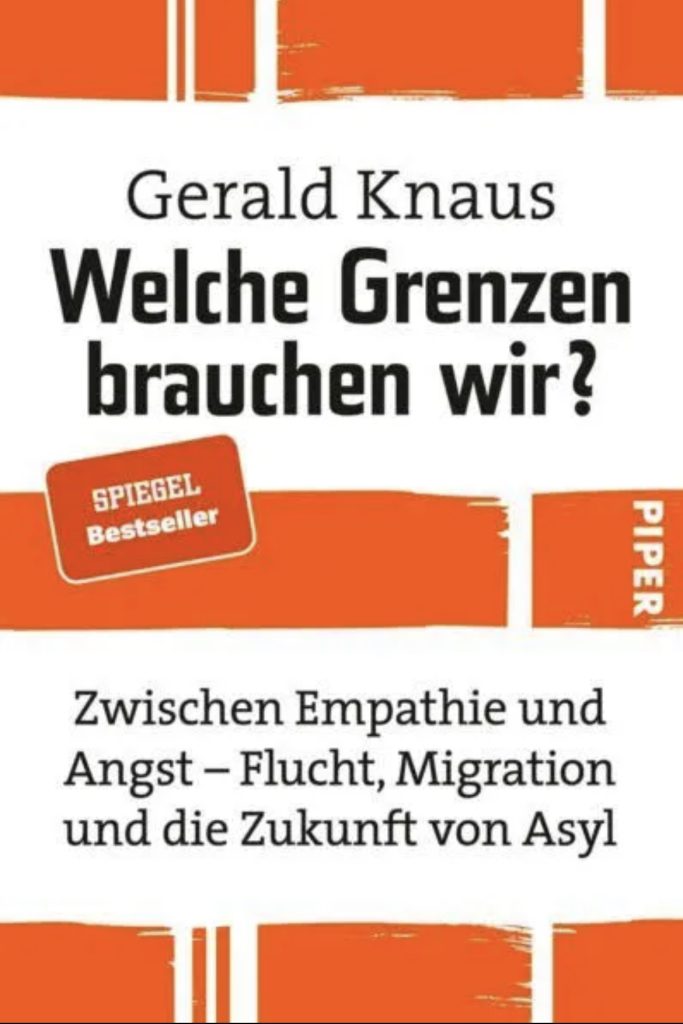

Viktor Orban sees him as a threat, Germany wants to implement his plans. Gerald Knaus, the man behind the Turkey deal, wants to save democracy with a humane migration policy. ‘You can change the world. I know that from experience.’

De Staandard

By Kasper Goethals

Saturday, January 21, 2023

This is an English translation from the original Dutch:

‘We moeten vechten tegen de krachten die het slechtste in ons naar boven halen’

One afternoon in late November last year, Gerald Knaus walks into Cyprus’ interior ministry. It is warm, a tropical sea breeze blows through the open door. No one asks the Austrian for his passport or searches his bags. A single guard nods politely. “Such a thing is only possible in a safe country,” muses the migration expert. “But this was not always so obvious here. In the late 1950s, the British occupiers tortured and executed young men who rebelled.”

In the entrance hall of the ministry, a screen hangs with images of asylum seekers and refugee camps. Knaus looks at it for a while. “Cyprus is experiencing the biggest asylum crisis in Europe,” says a female voice. “Every year the number of stranded people on the island increases. The Republic offers these people shelter and food, but the situation is unsustainable. Six per cent of the population is now made up of asylum seekers.”

Knaus leafs through his notes. “Applied to Germany, those percentages would amount to six million asylum applications in five years. Whereas Germany ‘only’ had 720,000 asylum applications to process in the record year 2016. If nothing is done, we will see the same harrowing scenes here as on the Greek islands. Everyone knows this is unsustainable. The only question is: what are we going to do about it?”

Asylum seekers in Cyprus have discovered the only safe route to the European Union. They come from all over the world with student visas to the Turkish part of the island. Then they walk on foot to the European part, or hitch a ride in the boot of a smuggler for a small fee. A wall or border fence is unthinkable, as Cyprus does not recognise the Turkish occupied territories and advocates for the unification of the island. Illegal pushbacks, as in the rest of Europe, are therefore impossible. Knaus, upbeat: “Cyprus must therefore look for a way to limit migration without using violence. This offers a unique opportunity to show that things can be done differently.”

Orban got it right

Gerald Knaus has been fighting for democracy and peace in Europe for 30 years. His close friend Rory Stewart, the former British development secretary with whom Knaus wrote a book on military interventions in Bosnia and Afghanistan, calls him a “deeply original thinker”. “Gerald believes in ‘principled pragmatism’. He has an unwavering belief in man’s ability to change things. And he has proven many times that he can,” Stewart says on the phone. “Gerald belongs to a small group of people actively fighting for the survival of European democracy. With great optimism, he throws himself into challenges that others see as frustrating or unachievable.”

To the wider public, Knaus is best known as the architect of the controversial March 2016 refugee deal with Turkey. Under the terms of the deal, it was agreed that people arriving by boat on the Greek islands should be ‘processed’ in Greece and sent back to Turkey. For refugees sent back, the EU offered protection to Syrian refugees from Turkey. In addition, the country received billions of euros meant for hosting refugees.

But it turned out differently. After the deal, the number of boat refugees fell by 97 per cent. The number of death by drowning dropped from 1,150 in 2015 to 130 in the two years following the deal. But the practical implementation ended in a fiasco. Thousands of refugees were trapped for years in wretched camps on the Greek islands. According to the United Nations, the deal was “possibly illegal” because money was paid to Turkey to take back refugees. Amnesty spoke of “madness” and of “a dark day for Europe”.

Knaus still stands by his proposal. He calls the criticism from NGOs “cynical”. According to him, they did not put forward any concrete alternatives, even though it was an important social problem. The camps on Lesbos were terrible, he agrees, but if the agreement would have been implemented correctly, these would not have emerged. “Massive uncontrolled migration as we experienced in 2015 is disruptive. When the population believes there is no plan at all, a sense of loss of control takes over. That is fertile ground for those who bring out the worst in people.”

According to Knaus, the extreme right understood this well. “It is shocking to re-read Viktor Orban’s speeches from that period. ‘In a few years, everyone will follow me,’ the Hungarian prime minister said. And in this, Orban has been proven right. Hungarian-style pushbacks have become the norm everywhere. Greece, Croatia, Poland, Bulgaria, you name it: everywhere migrants are kidnapped and thrown back across the border without accepting an asylum claim. It is wrong simply to accept that there is no alternative to this. Cooperation with countries of origin, but also with countries like Turkey, would be a logical solution.”

We are slipping

The morning after talking to the minister, Knaus sits in a café in the buffer zone between northern and southern Cyprus. The buildings are perforated with bullet holes. There are sandbags and checkpoints. Further away, UN soldiers in uniform drink their cappuccino. “The minister is interested in our proposal,” says Knaus. He advocates agreements with African countries so that they take back rejected asylum seekers. In exchange, there should be more legal migration and possibly even visa-free travel. Visa-free travel for Africans seems like a policy proposal doomed to failure, but Knaus is convinced it can be done. “We achieved things in the past decades that everyone thought were impossible.”

For Knaus and his associates in the small think tank European Stability Initiative (ESI), migration is just one priority. “We want a Europe capable of defending its democratic institutions and human rights standards against illiberal forces,” ESI’s website reads. “The fight for a humane migration policy is crucial because democracy is always tested hardest in prisons and at borders,” says Knaus. “There, people are tempted to commit human rights violations that can even be popular with the general public. It will not do to complacently sit back and blindly rely on our ‘strong institutions’. There is no guarantee that they will last, if we do not fight for them.”

Our institutions are already beginning to slip dangerously, the Austrian believes. He gives the example of pushbacks in Croatia. “All independent observers – the Council of Europe, journalists, NGOs, academics – noted that Croatia is carrying out pushbacks. Only the EU did not, because otherwise Croatia could not join the Schengen zone. In its ‘rigorous check’, the EU could not find ‘any evidence’ of pushbacks. That is like claiming that black is white and rain is sunshine. Such falsity is dangerous. When words no longer mean anything, the rule of law and democracy are worthless.”

Headscarves and pop music

It is getting late; we return to the centre of Nicosia. Knaus shows me across the dimly lit squares and through a maze of barbed wire and alleys. Our wheeled suitcases thunder through the deserted city with a hellish noise. “This is where the unaccompanied minors are,” he points out. A group of teenagers from West Africa look suspiciously as we pass. “This is where pregnant women and other vulnerable asylum seekers end up.” He keeps pointing and hurriedly shuffling around. “There is the church where Pope Francis prayed when he came to Cyprus to release asylum seekers stuck in no-man’s land and take them to the Vatican. It is also the office of Caritas.”

The main shopping street runs straight up to the Turkish half of the town. We can get through easily with our passports. Across, you enter a different world. The narrow streets are lined with peddlers selling chestnuts, pomegranates, and watermelons. Shops sell Turkish fruit, dürüms and Ottoman souvenirs. Everywhere you look, you see Africans. All of them have come here on student visas. Some to study, but also many with the plan to go over to the European side. In recent years, all sorts of shady ‘educational institutions’ have been popping up, which seem to be mainly concerned with organising migration. The largest number of asylum seekers in Cyprus now come from Nigeria, Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Knaus orders a Turkish pizza and sends a photo of the food to his daughters, who grew up in Turkey. It is indicative of his optimism, says his friend Stewart, that they went to Turkish schools. “Most of us wouldn’t dare.” Knaus doesn’t understand the doubt. “For them it’s normal, classmates who wear a headscarf when in the mosque and who like pop music. The daughters all learned Turkish.”

Along the way through Europe and Turkey, Knaus says he has gained a better understanding of human nature. “All the cities I lived in – Istanbul, Sarajevo, Sofia, Chernivtsi and Berlin – experienced ethnic cleansing in the last century. That is humbling. We have no different biology or psychology from that of our ancestors. Nothing intrinsic in us, no matter how much we would like to believe it, prevents us, or our children, from making the same mistakes. We have to fight the forces that bring out the worst in us.”

Great Europeans

Knaus is the grandson of a woman from Mariupol who was taken to Germany and was shot dead by the Soviets there in 1945. That is all he knows about her. His mother was stateless for 10 years after that and grew up in Austria, in hiding. The Soviets came looking for her twice.

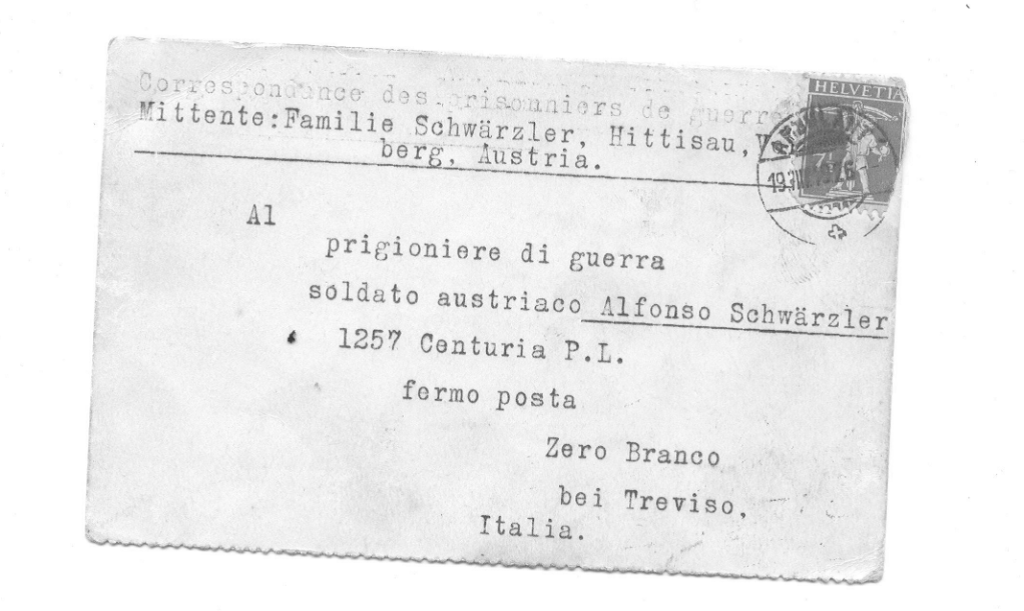

Both of Knaus’ grandfathers fought for Austria-Hungary during World War I, but on two different fronts. Gottlieb Knaus was soon, in 1914, captured by the Russians in the east. He spent 40 months in Siberia. The other, Alfons Schwärzler, fought against the Italians in the Alps and almost died in an avalanche. He was caught at the end of the war and taken to an Italian penal camp “where there was nothing to eat except thin rice soup”.

A family history of World War I – and a meaningless war

When Knaus went to study at Oxford, in 1988, a rare period of optimism began. The Berlin Wall fell, the Cold War ended. Knaus organised debates on “why Europe has more to gain from political union” and discovered ‘the great Europeans’ like Jean Monnet, who had “pulled the continent out of an endless spiral of violence”. To pay for his studies, Knaus was a tour guide to communist Albania, Yemen and former Yugoslavia. “I had never been to those countries myself, I only knew them from books, but afterwards the groups were always happy,” he laughs.

Knaus says he saw then a “glimpse of a different Europe, connected and free”, but things soon turned dark. He avidly read the diaries of imprisoned Czech dissident Vaclav Havel, who said that “hope is not the belief that things will get better, but the belief that what you are doing is right”. From Havel, he learned that a humane society is always fragile and yet possible. It fuelled his optimism, but he also saw too much violence to believe in Francis Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’. “I was in Zagreb after the first bombings. I saw the bridge in Mostar and the mosque in Banja Luka that had been blown up. In Albania, I saw museums cutting out murdered dissidents from photographs, as if they had never existed. It was a period of uproar, tragedy, and virulent, deadly nationalism. No one comes out of that naïve.”

Yet friends mostly remember his unflappable progress optimism. “He is fantastic,” Bulgarian philosopher Ivan Krastev says via email. The two met in Sofia, where Knaus came to teach for a time after his studies. They fought together for Bulgaria’s accession to the EU. “He combines enthusiasm about new ideas with great intellectual seriousness. It is always a pleasure to discuss with him.”

However, Krastev feels that Knaus’ struggles belong to the past. “He is a product of the 1990s, an exceptional era that will never come back. As long as we stay on course, we will achieve what we want, he thinks. Whereas I think we are in a different situation that requires a different approach.”

The marginal becomes mainstream

Knaus dismisses this. “History does not move in one direction. Both good and bad ideas can shape it.’ He tells of a lanky boy who was a year higher at Oxford. That boy, Jacob Rees-Mogg, was already fiercely opposed to the idea of European integration. “In 2016, the same Rees-Mogg campaigned for Brexit and he won. As students, many of us found his ideas ridiculous, outdated, marginal. It was an important lesson. Rees-Mogg persevered and was pragmatic. He rose to power, hammering his point endlessly. What was marginal became mainstream.”

But also “positive ideas from the margins” can become mainstream in this way, says Knaus. “After the 1990s, we campaigned for the lifting of the visa requirement for Albania and other Balkan countries.” At that time, Albanians were still dying at sea, during illegal crossings to the Italian Bari. “Everyone said it was impossible. Albania was seen as criminal, clichés about blood feuds and their “violent nature” were widespread. Nevertheless, after years of campaigning with the ministers of the interior in Europe, a breakthrough was achieved. After that it went fast. Today, citizens of countries such as Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia travel visa-free to the Schengen zone. They do not die in the refrigerator compartments of trucks or on old fishing boats.”

People are the stories they tell themselves, and each other, Knaus believes. He takes me to a village in the buffer zone of Cyprus. There is a mosque and a church. Cigarettes are sold at Turkish prices and shopkeepers sell banned products under the counter. In the middle of the village, an American runs a restaurant on two floors. Turkish food and Turkish beer are served at the top. At the bottom, guests eat and drink Greek food. The staff consists of a Syrian, an Iranian and an Iraqi. Knaus: ‘Take away the history here and this looks like an ordinary village, where the differences between people are of secondary importance. But this is not an ordinary village and you can’t just take away the history. If a murder is committed here, the United Nations Peacekeepers must come and address it.”

The German road

In Cyprus, Knaus promises everyone that he will urge the German government to find a solution to their problems soon. He seems firmly convinced that it will work. “There is good news coming,” he says. What Knaus does not say at that time is that he received a phone call a week earlier from the cabinet of the German Foreign Minister, Annalena Baerbock (Greens). He was asked whether he was interested to become the first special envoy for German migration policy. Only in the week after Christmas does Der Spiegel release the story.

Knaus declined the top spot. The job goes – much to Knaus’ satisfaction – to the liberal politician Joachim Stamp. “It is better that a politician does that job,” Knaus says on the phone that week. “I can do more from the sidelines. Stamp and I are in close contact. He might soon start the first negotiations with The Gambia and other African countries. He knows that there is no time to lose.’ Knaus emphasizes what that means: ‘Germany is going ahead, along with other countries that still believe in humane solutions in the fight against irregular migration.’

During a car ride from Nicosia to Larnaca, I overhear Knaus discussing matters with Adrian Praetorius, the German liaison officer in Greece in the field of migration. Praetorius does not want to be quoted, but his story agrees with what Knaus tells me. The German government wants an alternative to the pushbacks. Migration agreements with Africa are at the top of the list of priorities. Germany wants to find humane solutions to the migration crisis in voluntary coalitions with other countries, such as Switzerland and Austria. “In this way, someone like Viktor Orban cannot delay or stop initiatives at European level,” says Knaus.

Reverse Bataclan

After New Year, Knaus invites me to Klagenfurt, an Alpine town in southern Austria. The leadership of the Social Democratic Party (SPÖ) is meeting here to discuss migration. In the polls, the SPÖ is in a neck-and-neck race with the far-right FPÖ. As in Belgium, the number of asylum applications is historically high and is again becoming a key election issue.

If she can find a solution to this issue, SPÖ president Pamela Rendi-Wagner stands a good chance of becoming Chancellor in 2024. She has invited Knaus to explain his ideas on migration. “A great opportunity to pull Austria away from Orban’s camp,” says Knaus. “Under the previous Chancellor Sebastian Kurz, that path was widely pursued. There are also forces in that direction among the Social Democrats.”

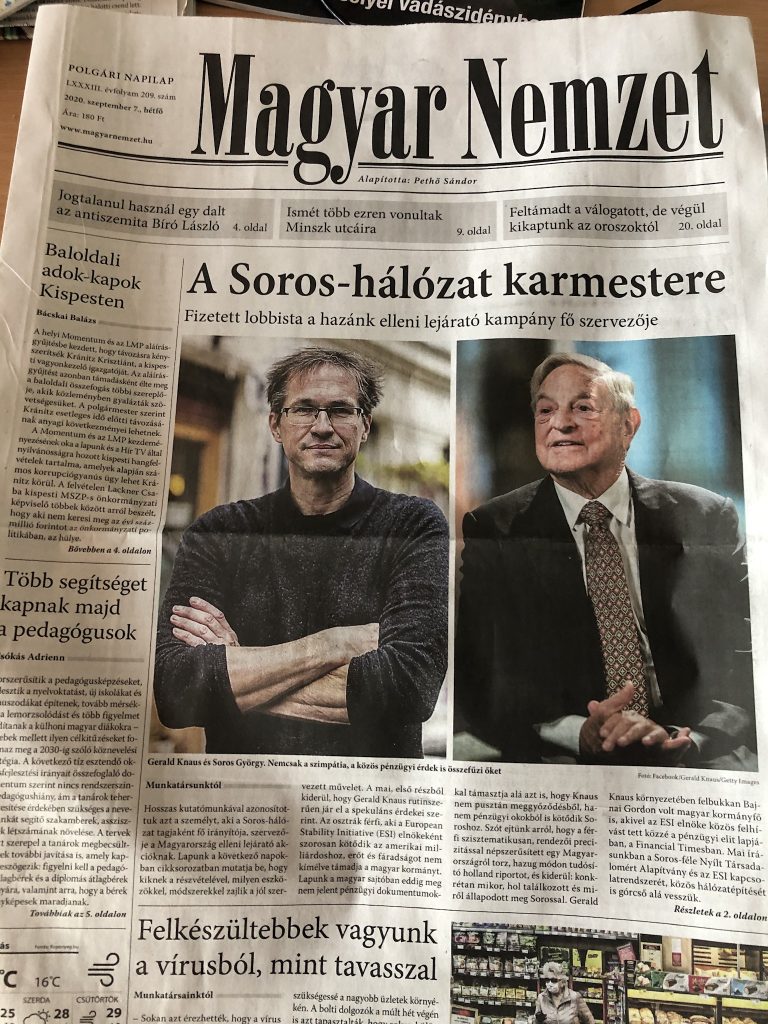

On the scenic train ride from Vienna to Klagenfurt, straight through the mountains, Knaus says Orban attacked him again over Christmas via the newspapers he controls. Since Knaus called him “the most dangerous man in the European Union” in 2015 and called for the suspension of EU subsidies to Hungary, state-run newspapers have been constantly attacking him. Knaus is described as a key figure in a global conspiracy to undermine Hungary. Knaus: “the most dangerous thing about Orban is not the plots, but rather his narrative of control and romanticism combined with language reminiscent of Europe’s darkest days.”

Knaus refers to Orban’s annual speech in Romania last summer. In it, Orban quoted The Army Camp of Saints, a 1973 book by French writer Jean Raspail. “I have read that book with horror. It is a far-right fever dream about a group of wild people from India overrunning France with a stolen fishing fleet. The book glorifies an armed response to migration and calls for genocide,” says Knaus. “Orban knows very well why he is quoting Raspail. He wants to mainstream the idea of migration as organised ‘repopulation’ and a ‘culture war.’”

This is precisely why the ideas of writers like Michel Houellebecq are also problematic, Knaus believes. “They poison the mainstream. Like Jacob Rees-Mogg in Britain, they nourish step by step the most inferior reflexes in human nature until they become widespread and common. This is not purely literary.” In media interviews, meanwhile, Houellebecq calls on French Muslims to emigrate, otherwise they will face a race war – ‘a reverse Bataclan’. “That rhetoric is not innocent. When Orban says: ‘The war starts at the border’, he means: we must also wage it in the cities.”

Finishing up in Klagenfurt

In Klagenfurt, Knaus debates behind closed doors with the party leadership of the Austrian Social Democrats. Afterwards, I speak briefly with chairman Rendi-Wagner. “I have known Knaus for three years and we have been consulting for longer. We share a belief in political policy based on facts. Especially on sensitive issues like migration. Knaus is not a theorist, but someone who provides us with practical, feasible solutions.” Asked about Orban, she says: “I believe in a politics of concrete European solutions, not hollow promises from populists. Not all 27 member states have to join right away. If it works, the rest will follow.”

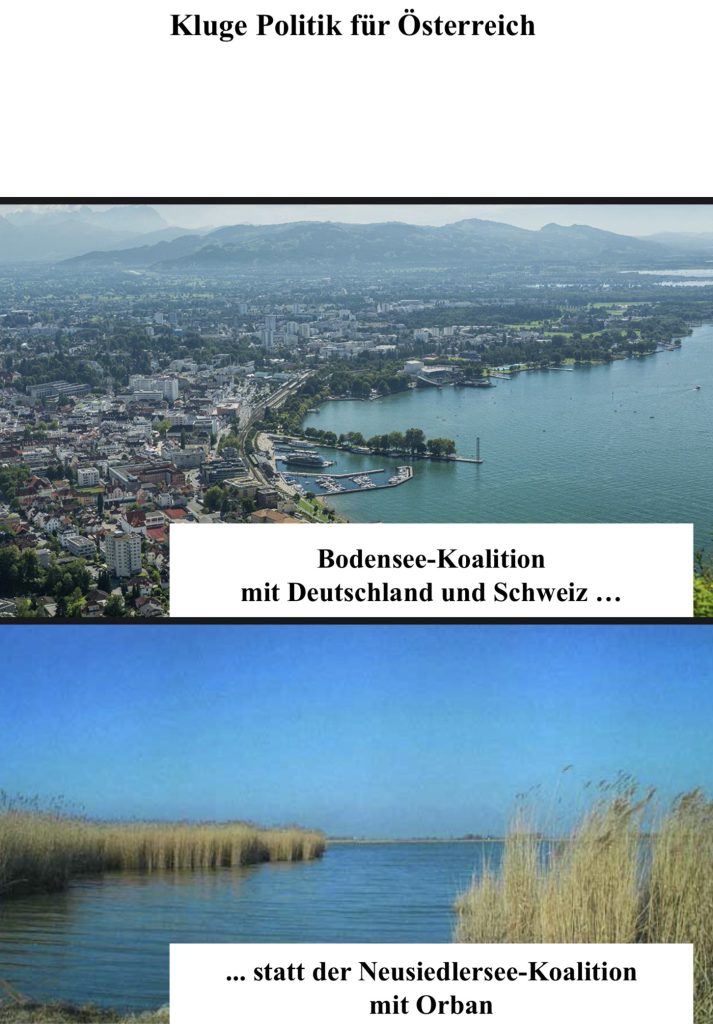

The next morning, I walk with Knaus around Wörthersee, Klagenfurt’s big lake. Knaus talks about the rule of law in Poland, a topic on which for years he has also been lobbying for, and about his hope that Rendi-Wagner will soon cite his proposal for a Bodensee-Allianz (a coalition of Austria with Switzerland and Germany) in her press conference. He talks about his time as a university lecturer in the Ukrainian town of Chernivtsi in 1993 and how the war threatened his friends there now. He recalls his memories of the elderly Jewish women he met then, who had miraculously survived the Holocaust.

Knaus: “You know who I would love to debate with?” He smiles. “Rutger Bregman. I’ve read his book ‘Humankind’ twice to see how he argues. It is very compelling, as a reader you gradually become captivated by his argument. There is only one problem: none of it makes any sense at all. Everything is pushed into the same mould to make a point that does not stand the test of reality. It is almost like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who sees the dangers of Islam everywhere and skilfully ignores all positive information about integration.”

Bregman clearly touches a nerve with Knaus. “The point that people are going to help each other more in a city that is being bombed is all well and good. But meanwhile, a city is still being bombed. That, too, is something being done by people. So are they virtuous?” The Austrian peered across the lake. “Here in Carinthia, the far-right receives the highest vote-share compared to anywhere in the whole country. They appeal to human nature, just as much as someone who calls for empathy and pity. This is precisely why the work is never over.”

In the hotel lift, Knaus tries in vain to load a web page on his phone. No internet. “What did she say? Did she adopt our idea?” Then his face brightens. “This gives hope for Cyprus. With this, we can claw further towards a different migration policy.”

He shows the title of the article: “Rendi-Wagner will ‘Bodensee-Allianz’ gegen illegale Migration”.