Slide presentation, discussion and public debate

Friday 26 November Haus der Musik (Vienna), 15:00

The future of liberal imperialism and European foreign policy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Minna Jarvenpaa |

|

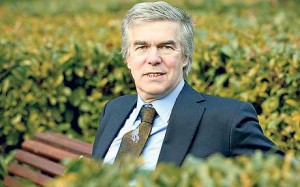

Gerald Knaus |

|

Miroslav Lajcak |

|

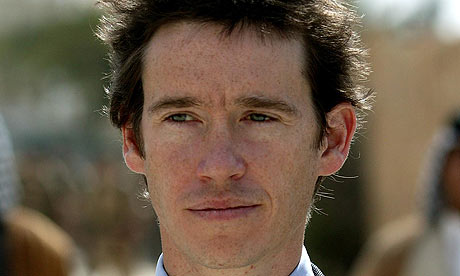

Rory Stewart |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ESI picture story: Liberal imperialism (2003)

In early 2010 Rory Stewart, then professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, and myself, a visiting fellow at the Carr Center, taught a joint weekly seminar on state building and intervention. Out of this grew an ambitious book project on the future of international interventions and an abiding interest in comparing experiences and possible lessons from the big interventions of the past two decades: Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Iraq and Afghanistan.

On Friday, 26 November 2010, Rory will come to Vienna. We will present at a public event jointly organised by Erste Stiftung and ESI, in the context of a debate on future visions for European foreign policy.

In Vienna we will be joined by two other panelists, experienced practitioners in the field of these ambitious state building missions.

One is Minna Jarvenpaa, who worked in senior positions for OHR (Bosnia), UNMIK (Kosovo), UNAMA (Afghanistan) as well as for former Finnish president Martti Ahtisaari. The other is Miroslav Lajcak, one of the most experienced European diplomats of his generation, former Foreign Minister of Slovakia, former High Representative in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and former Special Envoy in charge of dealing with the complex issue of Montenegrin independence.

For those who want to come to this event, please check out the official invitation here.

Also, if you are interested in doing some background reading on the topic, here are five of the most interesting background texts on the subject, capturing some of the debate in the past years.

Kofi Annan

1. Kofi Annan’s “Reflections on Intervention”

Against the background of a worsening crisis in Kosovo, UN General Secretary Kofi Annan gave a visionary speech on the future of intervention in 1998. He started out by presenting a traditional view in which “intervention” is seen as the enemy of state sovereignty and international law:

“Our century has seen many examples of the strong “intervening” – or interfering – in the affairs of the weak, from the allied intervention in the Russian civil war in 1918 to the Soviet “interventions” in Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan. Others might refer to the American intervention in Vietnam, or even the Turkish intervention in Cyprus in 1974. The motives, and the legal justification, may be better in some cases than others, but the word “intervention” has come to be used almost as a synonym for “invasion”. Article 2.7 of the [United Nations] Charter protects national sovereignty even from intervention by the UN itself. “

And yet, he continued:

“… in other contexts the word “intervention” has a more benign meaning. We all applaud the policeman who intervenes to stop a fight, or the teacher who prevents big boys from bullying a smaller one… a doctor who never intervened would have few admirers, and probably even fewer patients. So it is in international affairs. Why was the United Nations established, if not to act as a benign policeman or doctor? Our job is to intervene…”

What is the problem of the age? Annan described a new post-cold war world of collapsing, fragile and failing states, of warlords and ethnic warfare. In such as world the biggest challenge to security is no longer states fighting each other (a danger for which forms of containment offered a traditional strategy) but fighting their own citizens; and in which states collapse from within rather than being toppled from without. And thus he proceeds to assert a new doctrine, based on the notion that the suffering that is the result of civil wars and state failure cannot leave either the UN or other state’s indifferent: and that even the UN Charter protects the sovereignty of “peoples”, not “states”:

“This year we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights… the General Assembly had adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which puts all states under an obligation to “prevent and punish” this most heinous of crimes. It also allows them to “call upon the competent organs of the United Nations” to take action for this purpose. As for punishment, a very important attempt is now being made to fulfil this obligation through the ad hoc Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. And ten days ago in Rome I had the honour to open the Conference which is to establish a permanent International Criminal Court.”

The trauma of Rwanda is evoked as concrete illustration of the horrors of non-intervention: he refered to himself as “haunted” by the memory of actions for which he – as head of UN peacekeeping – was also responsible at the time:

“Personally I am haunted by the experience of Rwanda in 1994: a terrible demonstration of what can happen when there is no intervention, or at least none in the crucial early weeks of a crisis. General Dallaire, the commander of the UN mission, has indicated that with a force of even modest size and means he could have prevented much of the killing. Indeed he has said that 5,000 peacekeepers could have saved 500,000 lives. How tragic it is that at the crucial moment the opposite course was chosen, and the size of the force reduced.”

And then he made the immediate transition to the humanitarian crisis in Kosovo unfolding at that very moment:

“The last few months’ events in Kosovo present the international community with what may be its severest challenge in Europe since the Dayton agreement was concluded in 1995. As in Bosnia, we have witnessed the shelling of towns and villages, indiscriminate attacks on civilians in the name of security, the separation of men from women and children and their summary execution, and the flight of thousands from their homes, many of them across an international border. In short, events reminiscent of the whole ghastly scenario of “ethnic cleansing” again – as yet on a small scale than in Bosnia, but for how long? how can we not conclude that this crisis is indeed a threat to international peace and security?

This time, ladies and gentlemen, no one will be able to say that they were taken by surprise – neither by the means employed, nor by the ends pursued.

A great deal is at stake in Kosovo today — for the people of Kosovo themselves; for the overall stability of the Balkans; and for the credibility and legitimacy of all our words and deeds in pursuit of collective security. All our professions of regret; all our expressions of detemination to never again permit another Bosnia; all our hopes for a peaceful future for the Balkans will be cruelly mocked if we allow Kosovo to become another killing-field.”

Tony Blair – Gareth Evans

2. Tony Blair and Gareth Evans on the responsibility to protect

Less than a year later the theme of righteous intervention was defended in a speech of a British prime minister, Tony Blair, at the Chicago Economic Club in April 1999. The humanitarian crisis in Kosovo had given way to the first war ever fought by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation. As Nato planes bombed Serb forces, Blair said:

“Unspeakable things are happening in Europe. Awful crimes that we never thought we would see again have reappeared – ethnic cleansing. systematic rape, mass murder.… This is a just war, based not on any territorial ambitions but on values. We cannot let the evil of ethnic cleansing stand. We must not rest until it is reversed. We have learned twice before in this century that appeasement does not work. If we let an evil dictator range unchallenged, we will have to spill infinitely more blood and treasure to stop him later.”

He addressed the same dilemma which Kofi Annan had highlighted:

“The most pressing foreign policy problem we face is to identify the circumstances in which we should get actively involved in other people’s conflicts. Non-interference has long been considered an important principle of international order. And it is not one we would want to jettison too readily. One state should not feel it has the right to change the political system of another or foment subversion or seize pieces of territory to which it feels it should have some claim. But the principle of non-interference must be qualified in important respects. Acts of genocide can never be a purely internal matter. When oppression produces massive flows of refugees which unsettle neighbouring countries then they can properly be described as “threats to international peace and security”.

He then put the doctrine of intervention in the context of an emerging, interdependent, global community:

“We are witnessing the beginnings of a new doctrine of international community …”

Tony Blair thus outlined a “doctrine of the international community” based on the idea of a “just war”: a war to halt and prevent humanitarian disasters such as genocide or ethnic cleansing. United Nations secretary-general Kofi Annan raised the issue of humanitarian intervention in his speeches to the UN General Assembly in 1999 and 2000. And as a way to help forge a new international consensus the Canadian government established the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty in autumn 2000.

The report it published in December 2001 held that states have a “Responsibility to Protect”: where a population is suffering from mass atrocities, and the state is unwilling or unable to stop them, the principle of non-intervention is replaced by the international responsibility to protect. As one of the leading members of the Commission, former Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans, put it, the ambition was bold indeed: it was to “end mass atrocity crimes once and for all.” However, Evans was also careful to warn that this was not a doctrine legitimising any form of intervention:

“The responsibility to protect is not about conflict generally, or human rights generally, let alone human security generally, but rather about a small subset of cases where atrocity crimes are occuring, imminent or likely to occur in the foreseeable future if preventive strategies are not adopted.”

How many such cases might one anticipate? Evans notes that while there are at any given time hundreds of countries “subject of reasonable human rights concern” there are “only a dozen or so countries that can properly be regarded at any given time as being of responsibility-to-protect concern.”

Robert Cooper

3. Robert Cooper and liberal imperialism

Robert Cooper was one of the leading strategic thinkers in the UK government at the time of Blair’s 1999 speech on intervention as an advisor to the prime minister. He then moved to Brussels to become the leading EU foreign policy civil servant as Director-General for External and Politico-Military Affairs in the European Council under Javier Solana. Today he is again at the heart of efforts of building up a new European machinery (the External Action Service) for a common foreign policy.

Cooper also published in 2002 a widely discussed article “The new liberal imperialism”. This was followed by the book “The Breaking of Nations – Order and Chaos in the 21st Century”. These texts reflect both the Balkan experience and the new atmosphere of global crisis after the attacks on 11 September 2001. Cooper’s book begins with a warning in the very first sentences:

“The worst times in European history were in the fourteenth century, during and after the Hundred Years War, in the seventeenth century at the time of the Thiry Years War, and in the first half of the twentieth century. The twenty-first century may be worse than any of these.”

How could the 21st century be more dangerous than the period of two world wars or the utter devastation of the Thiry Years War, when one third of the population of Central Europe perished? The reason is the “spread of terrorism and of weapons of mass destruction”:

“Henceforth, comparatively small groups will be able to do the sort of damage which before only state armies or major revolutionary movements could achieve. A few fanatics with a “dirty bomb” (one which sprays out radiological material) or biological weapons will be able to cause death on a scale not previously envisaged.”

In his book Cooper divides the world into a post-modern world (the inter-dependent West), the modern world of traditional nation states and a pre-modern world. It is the pre-modern world, “the pre-state, post-imperial chaos”, a terra nullius, that poses, when allied to weapons of mass destruction, such a serious threat that it might even necessitate an armed intervention:

“The existence of such a zone of chaos is nothing new; but previously such areas, precisely because of their chaos, were isolated from the rest of the world. Not so today when a country without much law and order can still have an international airport.”

And:

“where the state is too weak to be dangerous, non-state acros might become too strong. If they become too dangerous for the established states to tolerate, it is possible to image a defensive imperialism. If non-state actors, notably drug, crime and terrorist syndicates take to using non-state (that is pre-modern) bases for attacks on the more orderly parts of the world, then the organised states will eventually have to respond.”

This is a major change in the international debate in security since the early 1990s. Then,Cooper noted,

“the chaos in Somalia and the breakdown of the state in parts of the former Yugoslavia excited pity, anger and shame, but they did not represent a direct threat to the lives or livelihoods of those living in safer, better organised territories … thus the initial Western response to the situation in the Balkans, in Somalia or Afghanistan was a combination of neglect, half-hearted peace efforts, plus a humanitarian attempt to deal with the symptoms, while steering clear of the (possibly infectious) disease.”

The lesson of 9/11, however, was that chaos in critical parts of the world matters and must be watched. It was not rival empires which brought down Rome, but the barbarian invasions.

What should be done when a zone of chaos turns into a major threat? Cooper presents no easy answer:

“The difficulty, however, is in knowing what form intervention should take: the most logical way to deal with chaos is by colonisation. If a nation state has failed why not go back to an older form – empire?”

Cooper sees clear problems with this, however:

“No Western country believes enough in their civilizing mission to impose their own rules permanently by force; nor could this be done, since the Western ideology is democratic and democracy cannot be achieved by coercion …Nor would traditional imperialism be acceptable to the peoples of failed states – except perhaps in an initial phase when they are rescued from chaos or tyrants.”

Here Cooper was much more cautious than many others who would come to accept a similar diagnosis of the threats posed by weak states . He noted that

“empire is expensive, especially in its postmodern voluntary form. Nation-building is a long and difficult task: it is by no means certain that any of the recent attempts are going to be successful. Great caution is required for anyone contemplating intervention in the pre-modern chaos.”

But at times a new, liberal imperialism may nonetheless be necessary.

James Dobbins – RAND Corporation building in Washington DC

4. Rand studies on Nation-building

Starting in 2002 ever more ambitious ideas emerged in the corridors of power in Washington DC. At the same time new thinking about “nation-building” (as Americans called it) was pushed forward by the world’s biggest think tank, the RAND corporation. A series of studies were produced which were soon widely quoted by practitioners involved in state building efforts. These studies, based on the case study method, expressed a simple core idea: that nation building interventions were above all a matter of organisation and resources. They were a managerial challenge above all.

The key argument is expressed in the aptly-titled “The Beginner’s Guide to Nation-Building”. Nation building is not only the inescapable responsibility of the world’s only super-power but it is also doable, if only the right lessons are learned from history. The authors of these Rand studies, under the leadership of former State Department intervention expert James Dobbins (who worked in senior positions on the Balkans as well as on Afghanistan), positioned different interventions on a spectrum from “co-option” (under which the intervening authorities “try to work within existing institutions”) to “deconstruction” (where the intervening authorities “first dismantle an existing state apparatus and then build a new one”):

“Where to position any given intervention along this spectrum from deconstruction to co-option depends not just on the needs of the society being refashioned, but on the resources the intervening authorities have to commit to that task. The more sweeping a mission’s objectives, the more resistance it is likely to inspire. Resistance can be overcome, but only through a well-considered application of personnel and money over extended periods of time.”

There are few references to the complexity of such missions, or to the serious possibility of failure, as Cooper had warned. There is little concern that interveeners might simply not know how to do nation building under certain conditions. For the Rand authors this takes becomes above all a matter of inputs and outputs:

“Mismatches between inputs, as measured in personnel and money, and desired outcomes, as measured in imposed social transformation, are the most common cause for failure of nation-building efforts.”

In a study of eight US-led nation building missions the authors underline:

“What principally distinguishes Germany, Japan, Bosnia and Kosovo from Somalia, Haiti and Afghanistan are not their levels of Western culture, economic development, or cultural homogeneity. Rather it is the level of effort the United States and the international community put into their democratic transformations.”

Putting in sufficient resources is the key to ultimate success. This is also important for another reason, as the authors of another Rand paper noted:

“There appears to be an inverse correlation between the size of the stabilization force and the level of risk. The higher the proportion of stabilizing troops, the lower the number of casualties suffered and inflicted. Indeed, most adequately manned post-conflict operations suffered no casualties whatsoever.”

Thus, with the right inputs, not only can almost all resistance be overcome; but this might also happened without any casualties!

If you are interested in these Rand studies:

Ted Galen Carpenter

5. Cato’s critique of nation building

As a leading libertarian think-tank in the United States, Cato favors limited government planning and is openly skeptical about “foreign military adventurism.” As such, the organization’s foreign policy department has worked hard to promote movement away from American imperialism. Scholars such as ed Galen Carpenter, vice president for defense and foreign policy studies at Cato, write extensively on nation-building. A typical argument is made in a short recent text Learning from our Mistakes: Nation-Building Follies and Afghanistan (Ted Galen Carpenter).

The author warns that all nation building missions are more or less doomed to failure:

“Afghanistan is an extremely unpromising candidate for such a mission, given its pervasive poverty, its fractured clan–based and tribal–based social structure, and its weak national identity. Furthermore, U.S. and NATO officials should be sobered by the disappointing outcomes of other recent nation–building ventures. The two most prominent missions, Bosnia and Iraq, ought to inoculate Americans against pursuing the same fool’s errand in Afghanistan.”

“The Dayton Accords ended the Bosnian civil war, but Bosnia is no closer to being a viable country than it was in 1995. It still lacks a meaningful sense of nationhood or even the basic political cohesion and ethnic reconciliation to be an effective state. If secession were allowed, the overwhelming majority of Bosnian Serbs would vote to detach their self–governing region (the Republika Srpska) from Bosnia and form an independent country or merge with Serbia. Most of the remaining Croats—who are already deserting the country in droves—would choose to secede and join with Croatia. Bosnian Muslims constitute the only faction wishing to maintain Bosnia in its current incarnation.

The economic situation is equally bad. Indeed, without the financial inputs from international aid agencies and the spending by the swarms of international bureaucrats in the country, there would scarcely be a functioning economy at all.

Although Bosnia is a nation–building fiasco, it eventually may be less of a disaster than Iraq. Americans who cheered the success of the surge strategy, and now swoon at the prospect of General Petraeus achieving a repeat performance in Afghanistan, were premature in their elation. Tensions are again simmering, both between Sunnis and Shiite Arabs and between Arabs and Kurds, and there have been numerous violent incidents. Months after national elections, the political squabbling is so bad that Iraqis have been unable to form a new government.

Moreover, Iraq has already ceased to be a unified state. Baghdad exercises no meaningful power in the Kurdish region in the north. Indeed, Iraqi Arabs who enter the territory are treated as foreigners—and not especially welcome foreigners. Although the Kurds have not proclaimed an independent country, the Kurdistan Regional Government rules a de facto state with its own flag, currency, and army.”

And he continues:

“Despite a 15–year effort and the expenditure of billions of dollars, the Bosnian nation-building mission is a flop. Despite a seven–year effort (and counting), the expenditure of at least $800 billion, and the sacrifice of more than 4,300 American lives, the Iraq nation-building mission is, at best, a disappointment Yet, instead of learning from those experiences, U.S. leaders seem intent on pursuing the same chimera in Afghanistan.

Foreign policy, like domestic politics, is the art of the possible. Containing and weakening al Qaeda may be possible, but building Afghanistan into a modern, democratic country is not. The increasingly evident failures of nation–building in Bosnia and Iraq—both of which were more promising candidates than Afghanistan—should have taught us that lesson.”

Some of the CATO studies that make this argument are the following:

Gerald Knaus – Rory Stewart

6. Finally, if you are interested in arguments made by Rory and myself, here are two short pieces on the same topic:

The European Raj (Gerald Knaus and Felix Martin) – 2003 / media reactions

and

The Irresistible Illusion (an essay Rory Stewart) – 2009 :

Here Rory argues:

“The fundamental assumptions remain that an ungoverned or hostile Afghanistan is a threat to global security; that the West has the ability to address the threat and bring prosperity and security; that this is justified and a moral obligation; that economic development and order in Afghanistan will contribute to global stability; that these different objectives reinforce each other; and that there is no real alternative. One indication of the enduring strength of such assumptions is that they are exactly those made in 1868 by Sir Henry Rawlinson, a celebrated and experienced member of the council of India, concerning the threat of a Russian presence in Afghanistan:

In the interests, then, of peace; in the interests of commerce; in the interests of moral and material improvement, it may be asserted that interference in Afghanistan has now become a duty, and that any moderate outlay or responsibility we may incur in restoring order at Kabul will prove in the sequel to be true economy.

The new UK strategy for Afghanistan is described as International … regional … joint civilian-military … co-ordinated … long-term … focused on developing capacity … an approach that combines respect for sovereignty and local values with respect for international standards of democracy, legitimate and accountable government, and human rights; a hard-headed approach: setting clear and realistic objectives with clear metrics of success.

This is not a plan: it is a description of what we have not got. Our approach is short-term; it has struggled to develop Afghan capacity, resolve regional issues or overcome civilian-military divisions; it has struggled to respect Afghan sovereignty or local values; it has failed to implement international standards of democracy, government and human rights; and it has failed to set clear and realistic objectives with clear metrics of success. Why do we believe that describing what we do not have should constitute a plan on how to get it? (Similarly, we do not notice the tautology in claiming to ‘overcome corruption through transparent, predictable and accountable financial processes’.)”

And Rory notes:

“We claim to be engaged in a neutral, technocratic, universal project of ‘state-building’ but we don’t know exactly what that means. Those who see Afghanistan as reverting to the Taliban or becoming a traditional autocratic state are referring to situations that existed there in 1972 and 1994. But the international community’s ambition appears to be to create something that has not existed before. Obama calls it ‘a more capable and accountable Afghan government’. The US White Paper calls it ‘effective local governance’ and speaks of ‘legitimacy’. The US, the UK and their allies agreed unanimously at the Nato 60th anniversary summit in April to create ‘a stronger democratic state’ in Afghanistan. In the new UK strategy for Afghanistan, certain combinations of adjective and noun appear again and again in the 32 pages: separated by a few pages, you will find ‘legitimate, accountable state’, ‘legitimate and accountable government’, ‘effective and accountable state’ and ‘effective and accountable governance’. Gordon Brown says that ‘just as the Afghans need to take control of their own security, they need to build legitimate governance.’

What is this thing ‘governance’, which Afghans (or we) need to build, and which can also be transparent, stable, regulated, competent, representative, coercive? A fact of nationhood, a moral good, a cure for corruption, a process? At times, ‘state’ and ‘government’ and ‘governance’ seem to be different words for the same thing. Sometimes ‘governance’ seems to be part of a duo, ‘governance and the rule of law’; sometimes part of a triad, ‘security, economic development and governance’, to be addressed through a comprehensive approach to ‘the 3 ds’, ‘defence, development and diplomacy’ – which implies ‘governance’ is something to do with a foreign service.”

For more: we look forward to see you at the Vienna event!

Haus der Musik – 26 November – 15:00