ЗОШТО МАКЕДОНИЈА НЕ Е ФИНСКА

Една од државите во светот за која сигурно очекувате да биде на врвот на сите национални рангирања сигурно е Финска. Не е важно што се мери – среќа, креативност, одржливост, родова еднаквост, благосостојба на децата…Финска секогаш завршува како глобален лидер.

Минатото лето патував во Финска за да научам повеќе за финската експертиза во менаџирањето на границите. Патував низ земјата со еден фински генерал и ги посетувавме границите со Русија, крајбрежната стража и аеодромот во Хелсинки учејќи за новите технологии и алатки за меѓународна комуникација во регионот на Балтичкото море.

Тоа беше една импресивна демонстрација на финската компетенција и потсетник за тоа како една мала нација е изложена геополитички со векови. Но, отвори и прашања – како финската нација станала толку просперитетна? Дали нивната приказна на напредокот и просперитетот содржи пошироки лекции и за други мали европски држави со проблематично минато и комплицирано соседство? Што би и требало на Македонија (Косово, Албанија, Босна или Србија) за да станат богати и просперитетни како Финска во некое време во иднина? Зошто Македонија не е Финска?

Во обид да „ископам“ што е можно повеќе за Финцките се обидов да ја најдам и прочитам сета достапна литература на германски и англиски. Се надевам дека моите фински пријатели ќе ме поправат доколку текстот содржи површни импресии и коментари и ќе ги додадат и своите гледишта.

Колку за споредба

Прво, нешто околу тоа како се мери успехот на земјата. Ако проучувате колку многу и колку различни интернационални рангирања постојат, сигурно ќе бидете во право ако решите да не ги земате пресериозно. Како и да е, земени како група рангирањата можат да раскажат интересна приказна. Еве една колекција од повеќе интернационали рангирања кои ги погледнав за минатата година пред да тргнам на пат кон Северот.

Постои Индексот на среќа на Обединетите нации кој е базиран на работата на Глобалниот институт на Џефри Сачс.

„Според извештајот за среќа на ООН од 2 Април Финска е рангирана како втора најсреќна земја после Данска“

Потоа, тука е и Индексот за просперитет од 2012 година каде што Финска е седма:

| 1 |

|

Норвешка |

| 2 |

|

Данска |

| 3 |

|

Шведска |

| 4 |

|

Австралија |

| 5 |

|

Нов Зеланд |

| 6 |

|

Канада |

| 7 |

|

Финска |

| 8 |

|

Холандија |

| 9 |

|

Швајцарија |

| 10 |

|

Ирска |

Потоа го имаме Индексот на одржливост на општествата каде што Финска повторно е во првите десет:

| Човекова благосостојба |

|

Економска благосостојба |

|

2006 |

2008 |

2010 |

2012 |

|

|

2006 |

2008 |

2010 |

2012 |

| Исланд |

5 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

|

Швајцарија |

9 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| Норвешка |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Шведска |

4 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

| Шведска |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

Норвешка |

12 |

9 |

3 |

3 |

| Финска |

3 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

|

Чешка |

8 |

5 |

4 |

4 |

| Австрија |

6 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Данска |

1 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

| Јапонија |

4 |

6 |

6 |

6 |

|

Финска |

6 |

7 |

7 |

6 |

| Швајцарија |

13 |

9 |

9 |

7 |

|

Естонија |

5 |

2 |

9 |

7 |

| Холандија |

12 |

14 |

14 |

8 |

|

Словенија |

3 |

4 |

5 |

8 |

| Ирска |

9 |

8 |

7 |

9 |

|

Австралија |

11 |

13 |

10 |

9 |

| Германија |

7 |

7 |

8 |

10 |

|

Луксембург |

2 |

12 |

8 |

10 |

Глобалниот индекс на креативноста се однесува на технологијата, талентите и толеранцијата. (Финска е прва во првите две категории):

1. Шведкса

2. САД

3. Финска

4. Данска

5. Австралија

6. Нов Зелан

7. Канада

8. Норвешка

9. Сингапур

10.Холандија |

Индексот за благосостојба на децата на УНИЦЕФ ја рангира Финска во првите 5 земји:

1. Холандија

2. Норвешка

3. Исланд

4. Финска

5. Шведска

6. Германија

7. Луксембург

8. Швајцарија

9. Белгија

10.Ирска |

Финска е и првата земја во светот која на жените им го дала правото на глас и правото да бидат бирани во парламентот. Првиот фински парламент во 1906 има 19 жени од 200 пратеници. Овој процент не беше достигнат во Турција се до 2011. Последниот Индекс за родовите разлики од 2012 покажува дека Финска се уште е лидер во однос на правата на жените и рамноправност на половите:

1.Исланд

2.Финска

3.Норвешка

4.Шведска

5.Ирска

6.Нов Зеланд

7.Данска

8.Филипини

9.Никарагва

10.Швајцарија |

Дури и неодамнешнио Индекс на земји со пријателска инфраструктура за велосипеди ја сместува Финска во топ петте земји:

1. Данска

1. Холандија

3. Шведска

4. Финска

5. Германија

6. Белгија

7. Австрија

8. Унгарија

9. Словачка

10.Обединето кралство |

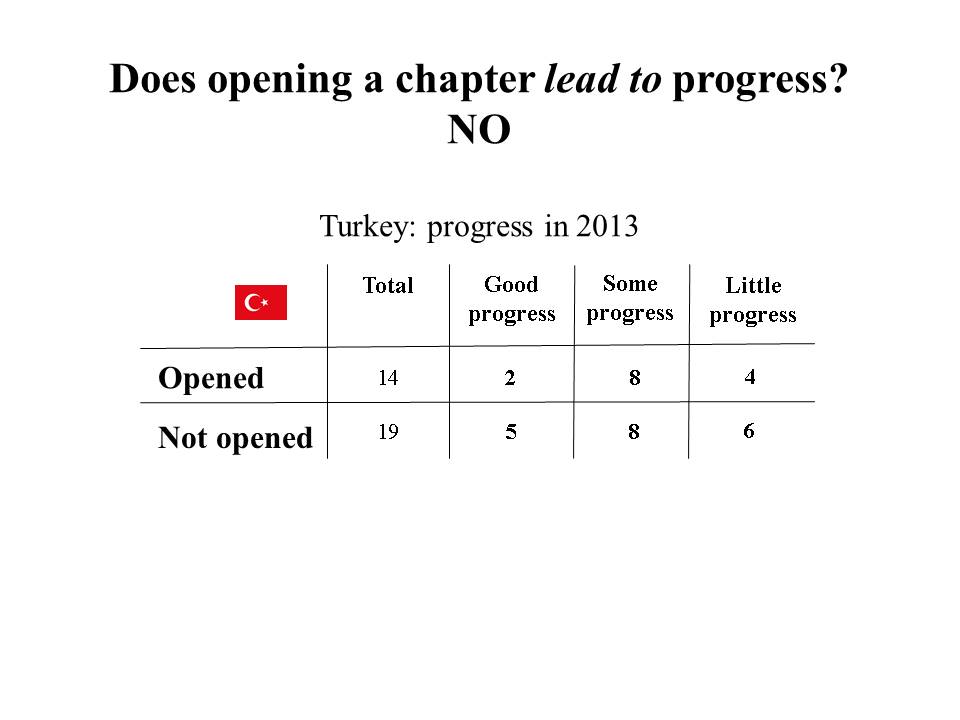

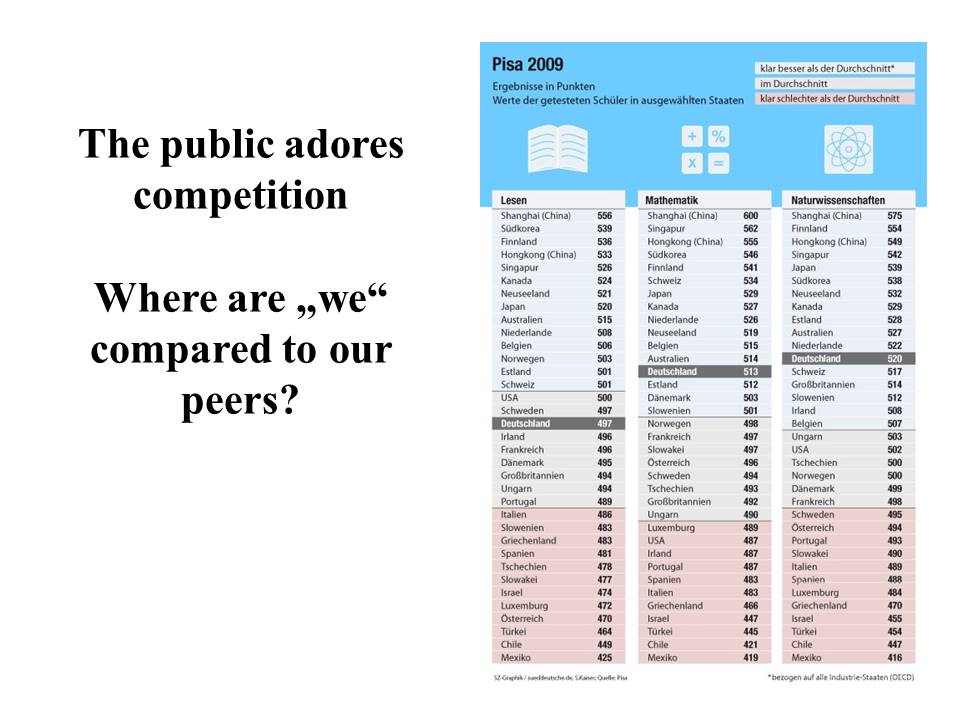

Конечно, рангирањата кои допринесуваат најмногу за тоа Финска да биде глобална сензација се ПИСА тестовите, односно Програмата за меѓународно оценување на учениците спроведена од Организацијата за економски развој и соработка (ОЕЦД). Тестовите мерат писменост, математика и научни вештини на 14 и 15 годишните ученици низ целиот свет. Финските резултати од овие тестови од 2001 наваму буквално донесоа илјадници делегати во северната земја кои сакаат да видат во што е тајната на финскиот успех.

Да, но зошто?

Накусо, на Финскаи оди добро. Очигледното прашање за Македонците, Албанците, Босанците и Србите кои гледаат на овие рангирања е дали тие воошто имаат некаква релевантност во нивните општества.

Која е причината и ефектот од ваквата успешна приказна? Дали е изненадување дека во општество во кое децата живеат добро и се здрави, растат во семејства чии родители живеат и работат во креативни градови и исто така, имаат добри училишта? Зарем не е очигледно дека држава каде што девојчињата живеат во околина која негува рамноправност на половите ќе биде подобра држава во однос на образованието што им се нуди на жените отколку патријархални општества каде што жените не можат да наследат земја како што е во случајот на Косово?! Дали финскиот успех е резултат на нивниот добар образовен систем…или е обратно?

Позади ова навидум нерешливо прашање лежи друго, поголемо прашање. Дали некој знае друга држава чиј што јазик го разбираат многу малку странци, а кои што успеале да произведат корисни патокази за домашните реформи?

“Ако племето од другата страна на реката преминало од камено во бронзено доба, тогаш вашето племе се соочува со изборот или да се држи до својата компаративна предност од каменото доба или да емулира со соседното племе во бронзената доба…стратегијата на емулација беше задолжителна премин-точка за сите нации кои денеска важат за богати“ (Ерик.С. Рејнерт)

Земете го образованието. Досега многу е напишано на тема „лекции од Финска“ и нивниот успех на ПИСА тестовите. Финските деца одат на училиште помалку часови од другите деца било каде на светот: 5.500 часа на возраст од 7 до 14 години споредено со повеќе од 7.000 часа во другите земји членки на ОЕЦД. Италијански петнаесетгодишник ќе оди на училиште две години подолго од негов фински врсник. Тие, исто така, тргнуваат две години порано на училиште. Италија е рангирана 32 во математика и наука и 27 во читање на ПИСА тестовите. Очигледно, успехот не е механички резултат на часовите поминати на училиште.

Ова покренува многу прашања. Што да се емулира? Што Финските ученици учат, кога тие не се во училиште? Во цело поглавје во неодамнешната книга за финското образование се опишува за учењето во не-училишната средина, улогата на музеите и библиотеките. Во 2010та година имало 790 главни и филијални библиотеки во Финска. Годишно, имало по 53 милиони посетители во библиотеките, а просечниот број на кредити по предметите годишно за секој Финец е 18. Би било интересно да се споредат статистиките од Македонија или Косово, почнувајќи со бројот на народните библиотеки и споредувањето на читателските навики Експертот за образование Паси Сахлберг, напиша:

Што прават учениците во Финска кога часовите им завршуваат порано за разлика од другите земји:? Во принцип, учениците слободно можат да си одат дома во попладневните часови, освен ако не им се нуди нешто во училиштето. Основните училишта се охрабруваат да организираат активности за најмладите после училиште и едуактивни или рекреативни клубови за постарите.

Тој додаде дека две третини од учениците на возраст од 10 до 14 години се дел од најмалку една младинска асоцијација.

Што се лекциите на политиката: Дали се тоа деца во земјите каде што има многу креативни симулации надвор од училиштето, па не треба да трошат премногу време за часовите… но, дали реверсот е точен во земјите кои немаат музеи или јавни библиотеки? Дури и во интернет ерата книгите и мрежата на јавни библиотеки е важна кога станува збор за симулирање на љубовта кон читањето? (Или, можеби е уште поважно кои видови на детски книги ќе се најдат на нивниот јазик, откако тие стапнале во библиотека?

Од друга страна, ако сѐ работи, бидејќи „тоа трае село да се едуцираат дете”, дали учењето на поединечните аспекти на финската политика нуди водич за македонскиот, косовскиот, албанскиот или босанскиот Министер за образование?

Всушност, вистинската лекција – главната поента е да се нагласи и дискутира од балканска перспектива – може да биде поинаква и многу базична. Не дека е најважен овој или оној аспект од финското образование, јавната администрација или социјалната политика. Тоа е општиот став кон напредокот и развојот, во смисла на она кои прашања најмногу значат, која обликува како да распределите дел од највредните ресурси … времето и вниманието.Реалната и значајна разлика меѓу Македонија и Финска се интересите на луѓето – носители на одлуки, родителите, наставниците – со што тие сметаат дека е доволно важно за да се борат сѐ додека не најдат поединечни подобрувања.

Sculpture in Helsinki overlooking the Baltic Sea Title: Happiness

Добро е познато дека финските учители се извонредно образовани. Во Финска наставниците во основно училиште мораат да имаат завршено магистерски студии и мораат да имаат направено вистинско истражување во образованието во рамки на студиите. Од нив се очекува да размислуваат сериозно за активностите во кои се впуштаат. Од нив се бара да размислуваат за основното образование, да поставуваат поинакви и нови прашања за тоа на што се базира и на што може да се базира успехот. На овој начин тие заземаат простор во широка национална диксусија.

Дали ова е дел од образованието на учителите низ Балканот? Дали учителите во Македонија или Косово имаат мислечки педагошки вештини? Дали образованието како такво е главен субјет на нивното образование?

А што е со креаторите на политики? Дали дебатите за образовните политики во Западен Балкан се продолжуваат на база на емириски истражувања? Дали реформите се темелат на реалните проценки на статус-кво? Дали образовните политики се дискутираат сериозно во националните парламенти?

Мислам дека повеќето од вас кои го читате ова ќе се посомневате дека воопшто постојат одговори на овие прашања. Но, како овие состојби можат да се променат? I

Да ги земеме резултатите од ПИСА од 2012 година и да ја споредиме Македонија со Финска:

ПИСА ресултати математика – 2012

| Шангај – топ држава |

613 |

| Холандија (топ ЕУ 15) |

523 |

| Естонија (топ ЕУ 13) |

521 |

| Хрватска |

471 |

| Србија |

449 |

| Турција |

448 |

| Бугарија (најслаба ЕУ држава) |

439 |

| Црна Гора |

410 |

| Албанија |

394 |

| Босна и Херцеговина |

– |

| Македонија |

– |

ПИСА резултати – читање 2012

| Шангај |

570 |

| Финска (топ ЕУ 15) |

524 |

| Полска (топ ЕУ 13) |

518 |

| Хрватска |

485 |

| Турција |

475 |

| Србија |

446 |

| Бугарија (најслаба ЕУ држава) |

436 |

| Montenegro |

422 |

| Albania |

394 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

– |

| Macedonia |

– |

ПИСА резултати – наука 2012

| Шангај – топ држава |

580 |

| Финска (топ ЕУ 15) |

545 |

| Естонија (топ ЕУ 13) |

541 |

| Хрватска |

491 |

| Турција |

463 |

| Србија |

445 |

| Кипар (најслаба ЕУ држава) |

438 |

| Црна Гора |

410 |

| Албанија |

397 |

| Босна и Херцеговина |

– |

| Македонија |

– |

Во 2012 Финска има најдобри резултати во наука и читање од сите членки на ЕУ. Полска и Естонија, исто така, имаат добри резултати. Србија е полоша од Турција. Албанија помина навистина лошо.

А Македонија? Воопшто и не зема учество на тестот! And Macedonia? It did not even take the test! Сето ова е сè повеќе и повеќе збунувачки со оглед на драматичните резултати кога Македонија го направи тестот, еднаш и за последен пат, во 2000 година:

“На најдолниот крај од скалата, 18 отсто од учениците од земјите на ОЕЦД и над 50 отсто од учениците во Албанија, Бразил, Индонезија, Македонија и Перу имаат Ниво 1 вештин или подолу. Овие ученици, во најдобар случај можат да се справат само со најосновните задачи на читање. Студенти кои учествуваа во тестот не се случајна група”, се вели во известувањето од тестот на ОЕЦД.

Процентот на студенти со сериозни потешкотии при читањето во 2000 е следниов:

|

Level 1 and below! |

| Финска |

7 |

| Полска |

15 |

| Унгарија |

23 |

| Грција |

25 |

| Бугарија |

40 |

| Македонија |

63 |

| Албанија |

71 |

Има и пошокантни детали:

|

под ниво 1 |

ниво 1 |

ниво 2 |

ниво 3 |

ниво 4 |

ниво 5 |

| Македонија |

35 |

28 |

24 |

11 |

2 |

0 |

| Албанија |

44 |

27 |

21 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

| Бугарија |

18 |

22 |

27 |

22 |

9 |

2 |

| Грција |

9 |

16 |

26 |

28 |

17 |

5 |

| Унгарија |

7 |

16 |

25 |

29 |

18 |

5 |

| Финска |

2 |

5 |

14 |

29 |

32 |

18 |

| Полска |

0 |

15 |

24 |

28 |

19 |

6 |

(Македонија токму сега по 14 поминати години реши да го земе учество во тестот по втор пат. Дали е ова можеби почеток на една поинаква дебата?)

Сите лидери имаат лимитиран буџет на внимание. Кои се мислите на премиерите и министрите кога си легнуваат навечер и кога се будат наутро? Кои прашања им ги поставуваат на странските гости? Таткото на модерниот менаџмент Питер Дракер, еднаш напиша:

“Ние со право сакаме да задржиме што е можно повече топки во воздухот како циркуските жонглери. Но, дури и тие го прават тоа околу 10 минути и не повеќе. Ако жонглерот пробуваше да го прави тоа подолго, сигурно кога тогаш ќе ги испуштеше топките“.

Најпосле, единствениот тотално нефлексибилен ресурс кај секој поединец е времето – родител или премиер – тоа е времето. Ова е се разбира точно и за политичката класа. На кои активности им се посветени? Што се дебатира во парламентот, во локалната самоуправа, во здруженијата на родители или наставници, што? Ако обрзованието не една од овие теми, тогаш е разбирливо зошто Македонија не може да фати чекор со остатокот од Европа. Може да се претпостави и дека моменталната генерација на млади кои излегуваат од училиштата нема да можат да се натпреваруваат со своите врсници низ Европа.

Но, како воопшто едно општество станало толку опседнато со човечкиот капитал, образованието и поттикнувањето на креативноста како што е оваа мала нордиска нација?

Во суштина, приказната за просперитетот и развојот на Финска е приказна за прераспределба на време и внимание. Тоа е приказна за фокус, за тоа како со текот на времето, делумните промени можат да доведат до драматични трансформации.

Финска не е отсекогаш успешна приказна за каква што ја знаеме денес. Овој успех е резултат на визијата на националната политика. Тоа е приказна за неверојатен успех.

“Финска без дилеми може да претендира за еден од најголемите успеси на модерната ера,” вака почнува предговорот на Дејвид Кирби во книгата „Кратка историја на Финска“.

Тој додава:

“Трансформацијата на она што безмалку еден век претставуваше лошо земјоделско земјиште на северната периферија на Европа во една од најпросперитетните држави на Европската унија денес е една извонредна приказна, но тоа воопшто не значи дека приказната е спокојна”.

Фред Синглтон ја започнува својата Куса историја на Финска вака:

“Денес Финците се една од најпросперитетните, социјално прогресивни , стабилни и мирољубиви нации во светот“.

Но, ќе запише Синглтон „домот на Финците од прва воопшто не ветуваше дека може да биде база за една успешна држава“.

Зошто успехот на оваа држава се именува како „неверојатен“? Повеќето пресметки за предодреденоста на успехот започнуваат со епската тема – природата. Фред Синглтон за ова ќе забележи „во текот на историјата Финска не можеше да привлече освојучи или трговци во една далечна земја на езера и шуми со студени зими“.

Со други зборови, природните богатства не можат да објаснат зошто Македонија е полоша од Финска денес. Ниту пак, климата. Финска има долги, темни и студени зими. Тогаш морето, главниот начин на транспорт, замрзнува во 90 проценти па мора вештачки да се одрзмнува за да може да биде функционално. Оваа клима претставува сериозно ограничување во земјоделството. Во северниот дел снегот ја покрива земјата дури 22 дена.

Успехот не е ниту прашање на суровини. Во споредба со своите соседи, Норвешка и Русија, Финска има ограничена природни ресурси, настрана шумите од бор и смрека кои покриваат половина од територијата. Поради студот, овде се е поскапо – од изградба на транспортни мрежа до фабрики за греење. Во 1918 година Финска уште беше првенствено земјоделски општество. Половина од нејзиниот БДП добиени од земјоделството. Повеќето не-земјоделски активности се фокусирани на дрво и пулпа.

А геополитиката? И дали балканските нации не се подеднакво „проколнати“ со својата географија?

Всушност, и геополитиката во Северна Европа во 20 век не е баш за оние со слабо срце. Со векови контролата врз Јужна Финска е од стратешко значење во големите борби за власт: помеѓу Шведска и Русија во 19 век; помеѓу Германија и Советскиот сојуз во 20 век.

Финците, исто така, се соочуваат со уште еден предизвик познат на балканските народи: јазичен конфликт. Со векови па до модерната ера, финскате елита зборуваше шведски. Финска икона од 20 век, генералот Густаф Манерхајм или финскиот ататурк – зборуваше многу подобро шведски од фински. На Финска и треба време за нејзината култура да биде признаена дури и од своите наблиски соседи, Швеѓаните.

Финците добиваат еднаков статус во администрацијата со Швеѓаните единствено во 1863. Кога еден барон во 1884 година на имот на благородништвото ќе се обрати на фински, тоа ќе предизвика сеопшт бес. Во 1880 помалку од една третина од училиштата се на фински јазик. Во 1900 тие се само две третини.

Реалноста на неодамнешното економско минато на Финска почива на длабока сиромаштија. Финците се соочуват со катастрафални времиња на глас во 1860 од кој што стотици илјади умираат. Слоганот по кој се живее во 1860 гласи „Природата го истура бесот врз нашиот народ. Емигрирај или умри!“ На почетокот на 20 век Финска е дом на земјоделци без земја и безимотни работници. почетокот на 20 век Финска беше дом на многу станари земјоделците и Безимотните работници. Во 1910 година повеќе од половина од фармите се помали од пет хектари, односно помали од минимумот со кој според прописите на Сенатот може да добијат субвенции. Ова ги потхранува политичките тензии и ги зголемува фрустрациите. Финските сиромашни селани се подготвени да ја излеат одмаздата кон побогатите земјоделци, па сето ова води до граѓанска војна веднаш по независноста во 1917 година.

Историјата на раната финска демократија е во знакот на конфликтите. Веднаш штом станува независна од руската импреија, Финска се втурнува во граѓанска војна помеѓу „Црвените“ и „Белите“. Исходот од војната само потврди дека германските трупи неминовно доаѓаат во Хелсинки. По инвазијата од страна на Русија во 1939 година, Финска беше принудена да ја отстапи територијата на посилниот сосед и да прифати поместување на 400.000 бегалци од Карелија. Потоа следи катастрофалниот сојуз на финската демократија со германските нацисти кога заедно се втурнуваат во „света војна„ за завземање на Карелија. Ова доведе од друга загуба на советсктите војници во 1944. Следи уште една војна против германските војници во Лапонија. На овој начин, во правата половина на 20 век Финците се бореа во три војни.

По втората светска војна Финска мораше да плати огромни репарации кон Советскиот сојуз. Повоена Финска беше принудена да расели стотици илјади, а остана и надвор од маршаловиот план и не доби американска помош. Финска дури не се ни приклучи кон Советот на Европа се до мај 1989 година.

По втората светска војна или непосредно пред навидум невозможната трансформација на грдото пајче во величествен лебед, финските лидери решаваат да ги напуштат сите поголеми геополитички аспирации. Тие се откажуваат од таканаречениот “Концепт на Голема Финска.” Нивните лидери сега го дефинирани финскиот национален карактер преку прагматизам. Манерхајм, генералот кој тогаш станува претседател, го предводеше патот:

“Манерхајм сфати дека Финска веќе не би можеле да биде бастион за судирите помеѓу христијанската цивилизација и варварските орди на болшевизмот. Немаше повеќе простор за крстоносните војни против исконските непријатели. Наместо тоа, имаше трезвени благодарност за тоа што ако Финска требаше да преживее и да успее како едно демократско општество, тогаш мораше да најде начин мора да опстојува во мир со џиновскиот источен сосед”, ќе забележи авторот Синглтон во книгата.

Синглтон ќе ја опише оваа точка на пресврт како вртење грб на романтичниот национализам.

Финска мораше „да се соочи трезвено и без илузии со мрачната вистина дека единствениот пат кој опстанокот води во обратна насока од оној кој претходно го следеа. Романтичниот национализам од 19 век кој одигра витална улога во формирањето на финскат нација повеќе не можеше да понуди ниту комфорт ниту поддршка“

Сега финските елити се фокусирани на растот, и покрај несигурното геополитичко соседство. Земјата систематски ги развива своите компаративни предности од дизајнирање на апарати за домаќинство до развивање дрвни продукти. Синглтон ќе забележи:

„Емерсон сигурно би можел да мисли на Финска кога рекол дека „ако човек може да ја напише подобрата книга или да направи подобра стапица за глувци од неговиот сосед, тој, дури и ако ја изгради својата куќа длабоко во шумата, светот ќе бетонира патека до неговата врата“.

Клучно за една од „подобрите стапици за глувци“ е финскиот образовен систем сам по себе. Во 1952 година 9 од 10 Финци имаат завршено само основно образование (7 или 9 години). Кон крајот на 1970 три четвртини од возрасните Финци имаат завршено само базична форма на образование. Финска беше извозник на работна сила се до 1980 кога бројот на Финци кои работат во Шведска изнесуваше 750.000 луѓе или најголемата емигрантска заедница во таа држава.

Да се образоваат луѓето најдобро што може, да се позајмуваат најдобрите идеи од другите и да се мотивираат луѓето во воспитно-образовниот процес….сето ова е центарот на финскиот идентитет. Класичната финска литература е интерпретирана токму во ова светло. Финската национална приказна е приказна за триумфот на образованието над сиромаштијата, триумф на умот над материјата. На наставниците во основните училишта се гледа како на носители на националните идеи. Тоа е наратив граден на морална бајка. Дури и финското национално движење од 19 век е интерпретирано низ образованието. Дури и на приказната од финскиот национален еп „Калевала“ се гледа како на славење на менталната агилност. Првата финска новела „Седум браќа“ е четиво кое ја слави вредноста на учењето.

Една симболична не-херојска приказна за креативноста насочена кон подобрувањето на животот доаѓа од учителката Маију Гебхард. Таа пресметала дека финските домаќинки поминуваат 30.000 часови од животот во перење и сушење на садови или еднакво на 3.5 години од нивниот живот. Така таа го измисли плакарот за сушење алишта кој денеска е инсталиран во секој фински дом. Финската фондација за иновации ова го смета за еден од најзначајните фински изуми на милениумот.

Креативност и секојдневен живот

Креативност и секојдневен живот

Всушност, финската приказна е како бајките – од партали до богатство. Како детските приказни за обичните луѓе кои се отпишани од сите како помалку вредни, а кои одеднаш застануваат под светлото на сцената и се испоставува дека се исклучителни.

Се уште не знам многу за Финска, но чувствувам дека нивната приказна вреди да се раскажува на Балканот. Во овој пост-хероиче наратив на една малечка земја, образованието се смета за тајната состојка на националната трансформација, еквивалент на спанаќот кој го трансформира Попај морнарот или магичната ламба на сирачето Аладин.

Тука е и централната лекција која нема ништо заедничко со бајките. Штедење на време и напор преку едноставни изуми за секојдневниот живот, креирање елегантна керамика за домаќинствата, промислување на сите аспекти на образовниот систем – сето ова бара време, но и уште повеќе внимание. Фокус. Фокус од страна на лидерите, интелектуалците и обичните луѓе.

Скопје 2014

А сега погледнете го Западен Балкан низ призма на раниот 21 век.

Погледнете ги нештата со кои се опседнати лидерите во Скопје. Големи престижни проекти на кои се фокусирани нивното време и внимание.(Да, некој можеби ќе рече „ете и тие позајмуваат нешто од соседите Грци, но, сепак, модерна Грција не е Финска со причина).

Погледнете ги нештата за кои дискутираат интелектуалците, академиците и политичарите во Босна и Херцеговина. Многу ретко тие дебати се за „правање подобра стапица за глувче“, а многу повеќе – ако постоеја бајки ние ќе имавме нов устав и сите одеднаш ќе бевме среќни.

Погледнете како се насочени времето, енергијата и парите на Косово. Колку споменици на војници се направија…а колку се направија библиотеки каде што би можеле да се образоваат идните генерации?

Веројатно сега можеме да дадеме одговор на прашањето зошто Македонија не е Финска. Недостига национален наратив кој ќе го слави прагматизмот, обичниот човек, образованието и просветителите како нациоални херои на иднината. Македонија застана онаму каде што беше Финска пред еден век во однос на зајакнувањето на позицијата на жената. Македонија не бега од националниот романтизам, туку напротив, се уште го слави.

Еден ден на Западен Балкан ќе се појават лидери со кои ќе се гордееме, лидри кои ќе градат музеи на науката и дизајнот наместо храмови на мртви воини и бандити. Но, кога ова ќе се случи, останува да видиме.