After 10 days of travel and research in Bulgaria and Brussels the plane from Sofia arrives back in Istanbul early on Saturday morning.

It is a glorious early spring day, warm and sunny. At 9 in the morning, as the taxi goes from the airport in the west of the city along the Byzantine walls towards the Golden Horn this metropolis is at its most attractive. There is little traffic, only some early pedestrians in the parks that stretch long the Marmara Sea. We cross the Galata bridge and continue along one of the most beautiful stretches of coast anywhere in Europe: from Ortakoy, underneath the first Bosporus bridge, to the affluent “village” of Bebek and further to the huge Ottoman fortress of Rumeli Hisari. We pass the fortress, turn left, and I am at home.

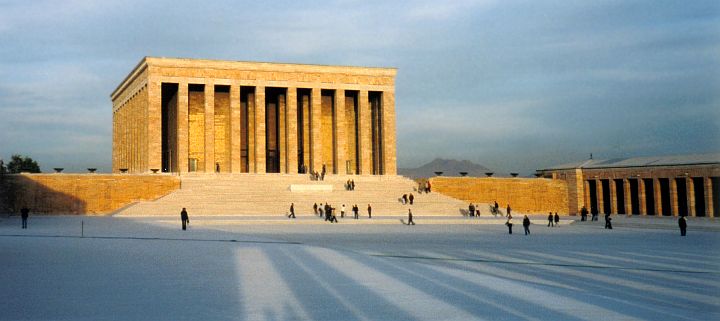

Mecidiye Mosque, Ortakoy (Istanbul)

Urban vitality

There is a game I have been playing for the last years upon every return to Istanbul after a trip abroad: to discover what has changed in the city this time. In fact, I do not remember ever having lived in a place – not post-war Sarajevo in 1996, not post-communist Chernivtsi in Ukraine in 1993, not transition Sofia in 1994 – where the feeling of witnessing constant change in the immediate physical environment has been as acute as in Istanbul today.

Today it is new, red road signs have been put up in all of Rumeli Hisari (and, I notice later, elsewhere in the city) during the past 10 days: quite elegant signs that indicate not only the names of streets that I have walked for years without knowing what they were called, but also the specific quarter (in this case Rumeli Hisari mahallesi) and the municipality (Sariyer). The signs have come accompanied by new red numbers pasted onto every house. Having struggled to find my way around the centre of Sofia, looking for non-existant street signs, only a day before makes me appreciate this change.

And it is not the only one that has transformed my mahalle: the reconstruction of the facade of a prominent old house in the main street leading up the hill from the Bosporus has also been completed. The enlargement of the pedestrian promenade along the water has also advanced. And these are just the changes I notice immediately upon arriving. It is this reality of small but continuous changes that conveys the sense of being in the most dynamic city in one of the most dynamic countries in Europe: a vitality and restlessness that does not cease to fascinate (one could make a long list of the large number of changes just in Rumeli Hisari in the past year).

Political crisis

Unfortunately, excitement and surprises in Turkey are today not restricted to urban improvement. There is a second aspect of life here that is no less constant: witnessing the twists and turns in an unending and often merciless power struggle that lies beneath the astonishing social and economic developments visible on the surface. It is almost a certainty that after a few days of absence reading a daily paper or visiting a Turkish website brings one face to face with the latest existential social crisis, atrocity, political turmoil or bitter confrontation, facts that often shock and surprise even the most seasoned observers of local politics.

To illustrate what I mean let me list only a few of the recent crises that have appeared like lighthing on a clear sky in recent years: the apprehension of two military men, caught planting a bomb in a bookshop in the town of Semdinli in late 2005. The murder of an Italian Catholic priest in his church in Trabzon. Protests preventing the holding of a conference discussing Armenians in the late Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. The assassination of a judge at the State Council in Ankara. The murder of Turkish Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in the centre of Istanbul. The killing of a group of missionaries in Malatya. A speech by (former) president Sezer warning that Turkey has never been in greater danger from turning fundamentalist. A dire warning by the Chief of Staff to the same effect. The removal of a prosecutor (in Van) who indicated that higher levels in the military might have been involved in the bombing in Semdinli. A violent demonstration in Diyarbakir, ending with young people killed in the streets by security forces. A terrorist attack by the PKK. Another terrorist attack. Media frenzy over an impending invasion of Northern Iraq. Airstrikes. An actual invasion of Northern Iraq. A frontpage story in March 2007, published in an Istanbul weekly (Nokta) how leading military officers were planning coups in 2004. The closing of that same weekly, never to reopen, a few days later, following pressure from the prosecutors. The opening of a trail against its editor. The threat of military intervention delivered through an email (the e-memorandum crisis) in April 2007. Mass demonstrations against the government. The sentencing of an academic who dared to question some aspect of the life of Ataturk. Trials of writers and journalists. The trial of Orhan Pamuk. The dissolution of a town council in South East Anatolia for using “languages other than Turkish” when providing services to citizens. The indictment of a Kurdish local politician. More indictments. A move to prohibit the DTP (Kurdish party) represented in the Grand National Assembly. The discover of a plot to kill the prime minister and his advisors in Ankara. The discovery of a large number of handgrandes in a house on the Asian side of Istanbul in summer 2007.

And finally, to top everything, the arrest of dozens of individuals who form an underground terrorist right-wing network in January 2008 and who appear to be linked to a large number of the incidents just listed … As I write this list I realise that I can easily do so from memory, without any real effort. I certainly have forgotten a range of smaller “existential crises”.

Every time one leaves Istanbul for a few days one thus returns to find the city that appears a bit richer, a bit more beautiful and yet also a city where the wildest political fiction is regularly surpassed by the reality of Turkey’s dark power struggles. Turkey is a bad country for those who do not want to believe in conspiracy theories. So this is a typical Bosporus weekend: walking along the water, drinking tea, looking at the rays of sun dancing on the small waves, enjoying a sense of peace and harmony, beauty and promise. And then turning to the papers and experiencing the opposite reaction: bewilderment.

Just consider the amazing turn politics took this weekend. On Friday evening (14 March) the Chief Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals, Abdurrahman Yalcinkaya, applied to the Constitutional Court to close the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), suggesting that it poses a threat to the secular order of the country. He calls for a ban on 71 of its leading members, including President Abdullah Gul and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, from politics for five years! Can this be true?

Turkish reactions

Most reactions in Turkey condemned the closure request. The daily Radikal titled on 15 March 2008: “It’s enough, anything else”, Taraf daily wrote: Put the Prosecutor on trail. On 17 March 2008 Sahin Alpay commented in Today’s Zaman: “The status quo fights back.” The Industrialist’s Association TUSIAD also criticised the motion: “In respect of Turkish democracy this trial is unacceptable.”

Instead of offering you my own analysis, let me quote a few of the local papers to share the full flavour of the local debate.

1. An article in Today’s Zaman:

“Left shocked by the lawsuit filed by the chief prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals against the powerful ruling party late Friday, pundits in Ankara have already begun to ponder how this judicial coup attempt will end. According to the Turkish Constitution, there is no timeframe for the Constitutional Court to decide on a party closure file. But, in 1997, it took only eight months for the court to close the Welfare Party, the predecessor of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP). This shows that there is not much time for the political engineers in the capital to direct developments to their advantage.

But what is more important then the timeframe is the member composition of the Constitutional Court, which has closed 40 different political parties since its foundation in 1961. Fikret Bila, daily Milliyet’s columnist, underlined this reality in his column yesterday but also drew attention to the fact that the parties were banned because of either acting against the unitary regime of the Republic or being a focal point of anti-secular activities. The ban of two political parties has been asked for: The AKP and the Democratic Society Party (DTP), Bila said, pointing out that the predecessors of these two parties were also closed down by the top court on the same charges.

Another point is that the general composition of the top court has not changed in the last 10 years. Political observers argued that the majority of judges in the Constitutional Court were appointed by former President Ahmet Necdet Sezer, a staunch secularist who was elected as president when he was the head of the top court in 2000. Out of 11 judges, at least seven of them would vote for the closure of the AKP, these observers claimed. Apart from these predictions, the court’s ruling last year to annul the presidential elections in Parliament with the votes of nine judges shows that life will no longer be easy for the AKP. But the court will signal its possible ruling on the closure of the AKP through another decision on the annulment of the recently approved constitutional amendments package that lifts the headscarf ban in universities, a move that sparked harsh accusation against the government from the judiciary and the military. Observers in the capital argued that if the court annuls the constitutional amendment on the basis of secularism principle of the Republic that will also send a strong warning to the ruling party.

In the event of the AKP’s closure, the ruling party will not only lose its chairman and Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan but also 41 seats in Parliament. The current government will collapse in the absence of its prime minister. But the AKP’s remaining 299 deputies could still form a new party, elect a chairman and of course the new prime minister of the country. Many observers argued that the party would face an in-house race for the party’s leadership but the new prime minister will be someone selected by Erdoğan himself. There are already names being mentioned in the capital for the leadership of the party such as Deputy Prime Minister Cemil Çiçek, Justice Minister Mehmet Ali Şahin, Foreign Minister Ali Babacan, Interior Minister Beşir Atalay, Parliament Speaker Köksal Toptan. Abdüllatif Şener who refused to participate in the July 22 general elections from the AKP ranks, is also seen a potential leader of the new party but Şener cannot be prime minister as he is not a lawmaker. Another possibility is that the country could face snap general elections as a result of the AKP’s closure depending on how long the file remains in court. The country will hold local elections next year in March, where general elections could also be held if the AKP’s possible successor decides to do so. The votes of 276 deputies suffice for calling a general election. Let them close us, we would get 50 percent of votes, Şahin told reporters in Antalya over the weekend. But there are more optimists among the AKP members. This time we’ll receive 70 percent of votes, said Bülent Arınç, an AKP heavyweight.”

2. An article by Fehmi Koru:

“We aren’t accustomed to having solely an “indictment,” written by the chief prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals, without a process — a process of a military intervention, prepared and executed by masters of psychological warfare. In 1960, after the army takeover, the military rulers brought all the politicians who had served the country in the proceeding 10 years before a specially designed tribunal, whose handpicked members tried them for misdemeanors. President Celal Bayar was accused of embezzling a gift horse. No kidding. The panel of judges later found that the horse had been delivered to a zoo together with a hound, also the gift of an Afghan king. The chairman of the panel waved a piece of ladies’ underwear in the face of Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, accusing him of secret liaisons, but it was later discovered that the underwear had been planted by a friendly hand. Prime Minister Menderes was also accused by the same tribunal of fathering a child out of wedlock. In 1980, after the army intervened, the new military rulers opened up court cases against politicians and their parties. Soon afterwards they closed all the parties and banned the politicians from politics. Almost all the politicians were brought before special tribunals, and their miserable spectacle they presented during these trials gave away the reality that they had been subjected to harsh torture and mistreatment.

Mere indictment by a chief prosecutor for the closure of a political party is a new phenomenon in Turkish politics. No direct military intervention, no taking politicians prisoner, no sending political leaders to exile, not even any forcing of a government from power… Only an indictment written by the chief prosecutor… The chief prosecutor has obviously spent a lot of time on preparing the text of the indictment. The 162-page text is made up of accusations against Justice and Development Party (AK Party) politicians, including President Abdullah Gül, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and former Parliament Speaker Bülent Arınç. The chief prosecutor collected all the utterances of AK Party politicians — the utterances he felt were against the secular foundation of the state — going back to the time they were members of the now-banned Welfare Party (RP).”

3. A comment by Sahin Alpay:

“chief prosecutor has asked the Constitutional Court to ban the ruling Justice and Development Party (AK Party) for allegedly having become a center of activities threatening the secular regime. This move is surely a severe attack against democracy, the rule of law and stability in Turkey. It is a shame for the country. The accusations leveled against the AK Party are wholly unjustified and have no legal basis, only an ideological one. It seems that the self-appointed bureaucratic guardians of the state want to punish the AK Party for not only daring to elect Abdullah Gül, whose wife wears the headscarf, as president, but also for trying to lift the headscarf ban at university, which has long been the symbol of authoritarian secularism. One can only hope that the Constitutional Court rejects this provocation against democracy and that Parliament finally moves to adopt the necessary constitutional and legal amendments to bring regulations concerning political parties in line with liberal democratic norms.

The chief prosecutor had previously asked the Constitutional Court to ban the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society Party (DTP) and now he is moving against the AK Party government, which received 47 percent of the national vote in last summer’s general election. These moves by the chief prosecutor indicate that the bureaucratic establishment in Turkey wants to uphold state policies adopted in the 1920s and 1930s under an authoritarian single-party regime. Those policies, drawn in line with the notion of modernity that prevailed in the founding period of the republic, essentially assigned the state the duty of secularizing society. This amounted to isolating society from the influence of Islam, which was regarded as the main source of the country’s backwardness. Identity policies adopted at the time were aimed at the forced assimilation of minority cultures into the majority culture.”

4. A comment by Bulent Kenes (columnist with Bugun and Today’s Zaman):

“Expecting this much from those who resorted to a midnight e-memorandum, those who provoked a certain segment of society to take to the streets while heaping all sorts of insults on the other segment, those who invented the problem of the “367 requirement” — at the cost of contravening the law — just to keep Sezer as president and those who tried to prevent the general elections by attempting to engage the country in a war in 2007 cannot be considered unreasonable. However, we are only human, and we are innately predisposed to looking at future possibilities optimistically, and we thought that this segment, however enraged it may be, would not dare to draw the country into a political turmoil and chaos it could not handle, thinking that they were on the same ship as us. But today what we understand from their efforts to have the ruling party shut down is that we have been a bit too optimistic.”

5. A comment by Yavuz Baydar (columnist with Sabah and Today’s Zaman):

“If the case is accepted, we shall have unprecedented case in world politics: The parties chosen by more than half of the voters will have faced an annulment of their political will, by the judiciary — the AK Party and Democratic Society Party (DTP), the latter earlier charged with separatist terror. Indictments question the legitimacy of some 360 seats of a total of 550 in Parliament. In other words, Turkey’s democracy is being led into a huge crisis with an unknown outcome.

In such a case the AK Party could, and should, take the lead: First, it should convene Parliament immediately and seek a consensus of urgent and comprehensive constitutional reform with revision also of the Political Parties Law. Second, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and Foreign Minister Ali Babacan should immediately visit Brussels and meet with major EU leaders in order to declare a national plan for democratic reform and a clear-cut road map for the rest of the year. It should immediately amend Turkish Penal Code (TCK) Article 301 to show its commitment to the democratic project in accordance with the EU. It is up to Erdoğan to convince the wide democratic opinion of Turkey that the AK Party will return to policies of change on a broader basis.

The AK Party’s only chance to save democracy is to again widen its circle of domestic alliance, re-embracing alienated non-AK Party segments for further reform and pressure Turkey’s friends in the EU to raise the level of support for a stable future. From today serious things are at stake, and hidden efforts will have a backlash.”

6. A comment by Mustafa Akyol (Turkish Daily News):

“The 21st century tactic is to stage coups via not the military but the judiciary. As I noted in my piece dated Jan. 24 and titled “The Empire Strikes Back (Via Juristocracy),” now the bureaucratic empire in Ankara attacks the representatives of the people with legal decisions, not armed battalions. If you talk to them, they will proudly tell you that they are saving Turkey from Islamic fundamentalism. You have to be a secular fundamentalist – or hopelessly uninformed – to believe that. The AKP has proved to be a party committed to the democratization and liberalization of Turkey, a process which, naturally, includes the broadening of religious freedom But that democratization and liberalization is the very thing that the empire fears from. If you look at the “evidence” that the chief prosecutor presented to the Constitutional Court to blame the AKP, you will see how fake all this “Islamic fundamentalism” rhetoric is. The anti-secular “crimes” of AKP include:

- Making a constitutional amendment in order to allow university students to wear the headscarf. (Maddeningly enough, this bill was accepted in Parliament with the votes of not just the AKP’s deputies but also those of the Nationalist Movement Party [MHP], and the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society party.)

- Supplying free bus services for the student of the religious “imam-hatip” schools, which are nothing but state-sponsored modern high schools that teach some Islamic classes in addition to the standard secular education.

- Naming a park in Ankara after the deceased leader of a Sufi order.

- Not allowing the public display of a bikini advertisement.

- Employing headscarved doctors in public hospitals.

- Allowing one of the local administrators to issue a paper which has the criminal sentence, “May God have mercy on the souls of our colleagues who have passed away.” (The simple fact that he dared to mention God [“Allah” in Arabic and Turkish] in an official setting was considered as a crime.)

Yes, this is absolutely crazy. It is like defining the Republican Party in the United States as an “anti-secular threat” and asking for its closure based on facts such as that it has pro-life (anti-abortion) tendencies and that President Bush publicly said that his favorite philosopher is Jesus Christ. The heart of the matter is that Turkey’s self-styled secularism is a fiercely anti-religious ideology akin to that of Marxist-Leninist tyrannies. And the AKP has been trying to turn Turkey into a democracy. That’s the party’s real “crime.””

7. Finally, a comment by a former Turkish ambassador to Germany and deputy leader of the major opposition CHP, Onur Öymen :

“The AKP’s members cannot expunge their guilt by blaming the judiciary for their actions. Everyone needs to respect the judicial process from now on. Parties need to respect the law.”

The opposition CHP noted that decisions by the courts “have to be respected”. Deniz Baykal, the CHP chairperson said: “the indictment is a legal one. It was not prepared with political aims and hostility; and it does not reflect emotional reactions. It was prepared objectively and within the borders of laws and responsibility.”