A crisis of trust

The ESI Roadmap Proposal for Enlargement

Belgrade presentation, November 2014

The ESI future of enlargement project is supported by ERSTE Stiftung in Vienna

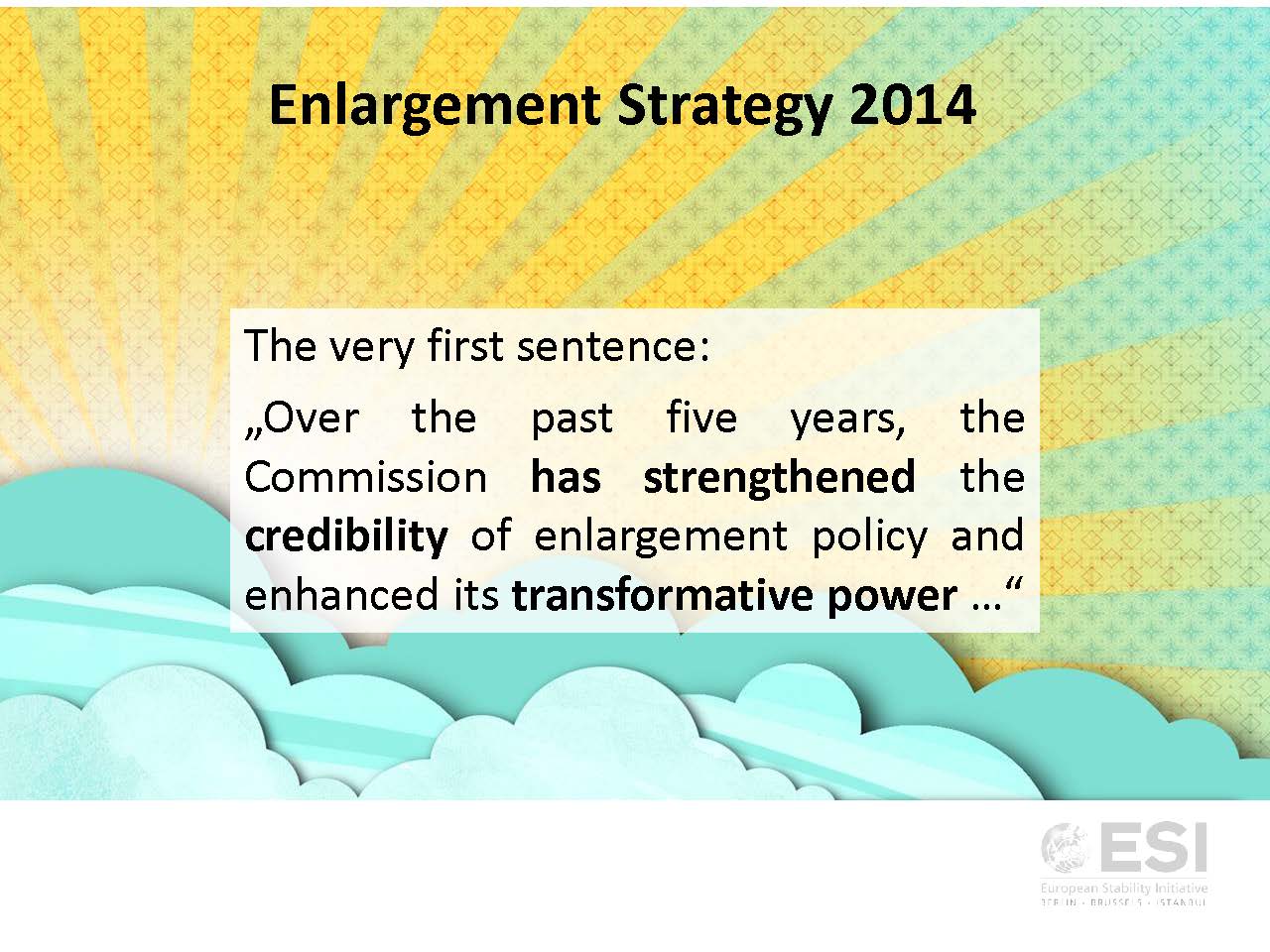

Every year the European Commission publishes its Enlargement Strategy. The 2014 Enlargement Strategy, presented in October, starts out on a very optimistic note with the following sentence:

This assertion raises questions, though. How does the Commission measure the credibility of enlargement policy? For whom is enlargement policy more credible today than five years ago?

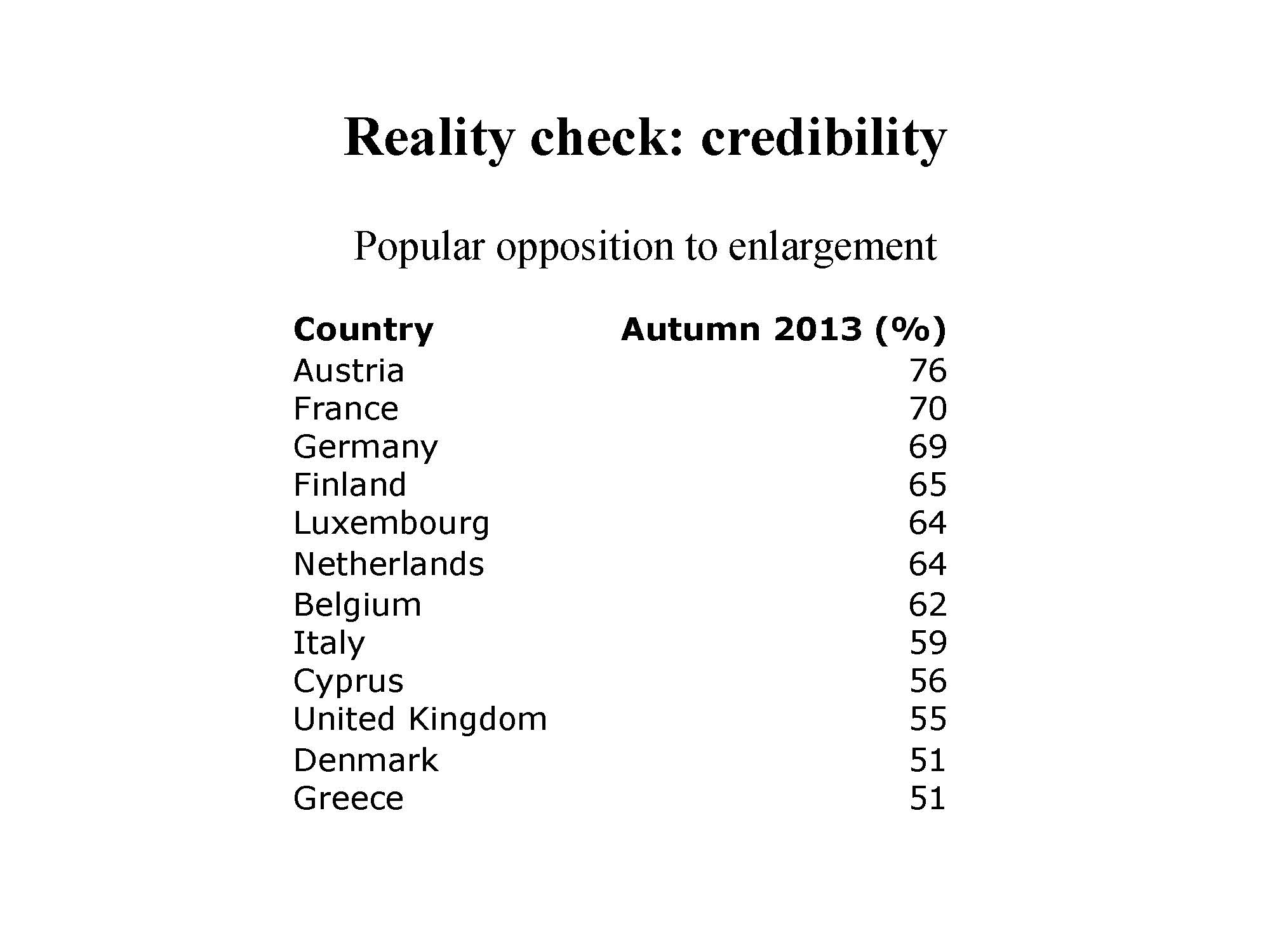

Here is a reality check. Eurobarometer surveys in 2008 and 2013 show growing opposition to enlargement in every single EU member state: old and new, rich and poor, those hit hard by the global economic crisis in 2008 and those relatively unscathed.

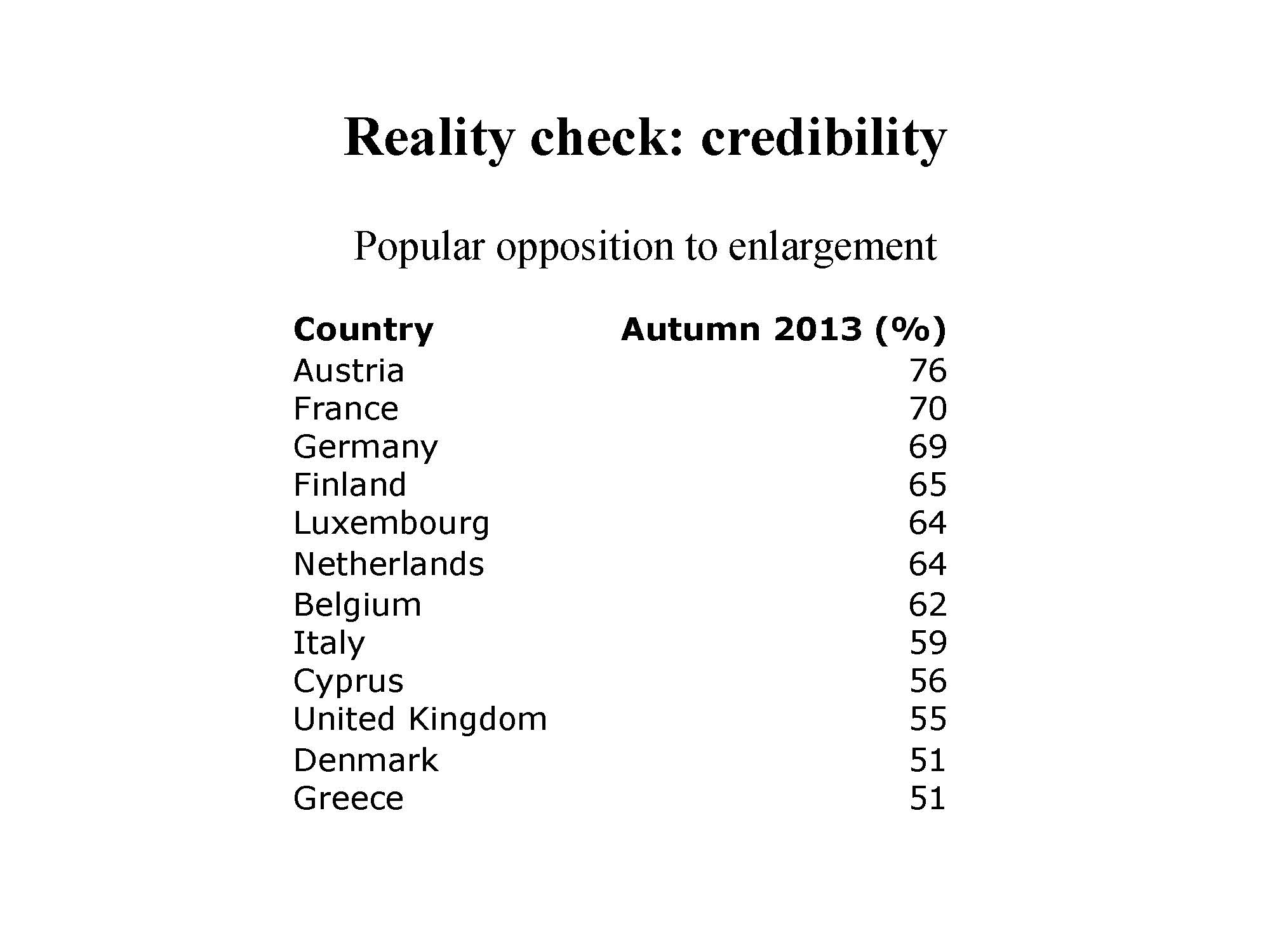

Enlargement has never been less popular in the EU than now. The 2013 Eurobarometer survey shows that an absolute majority of EU citizens oppose further enlargement (52 per cent). Opposition is stronger among euro area respondents (60 per cent). This table shows the significant lack of support for enlargement:

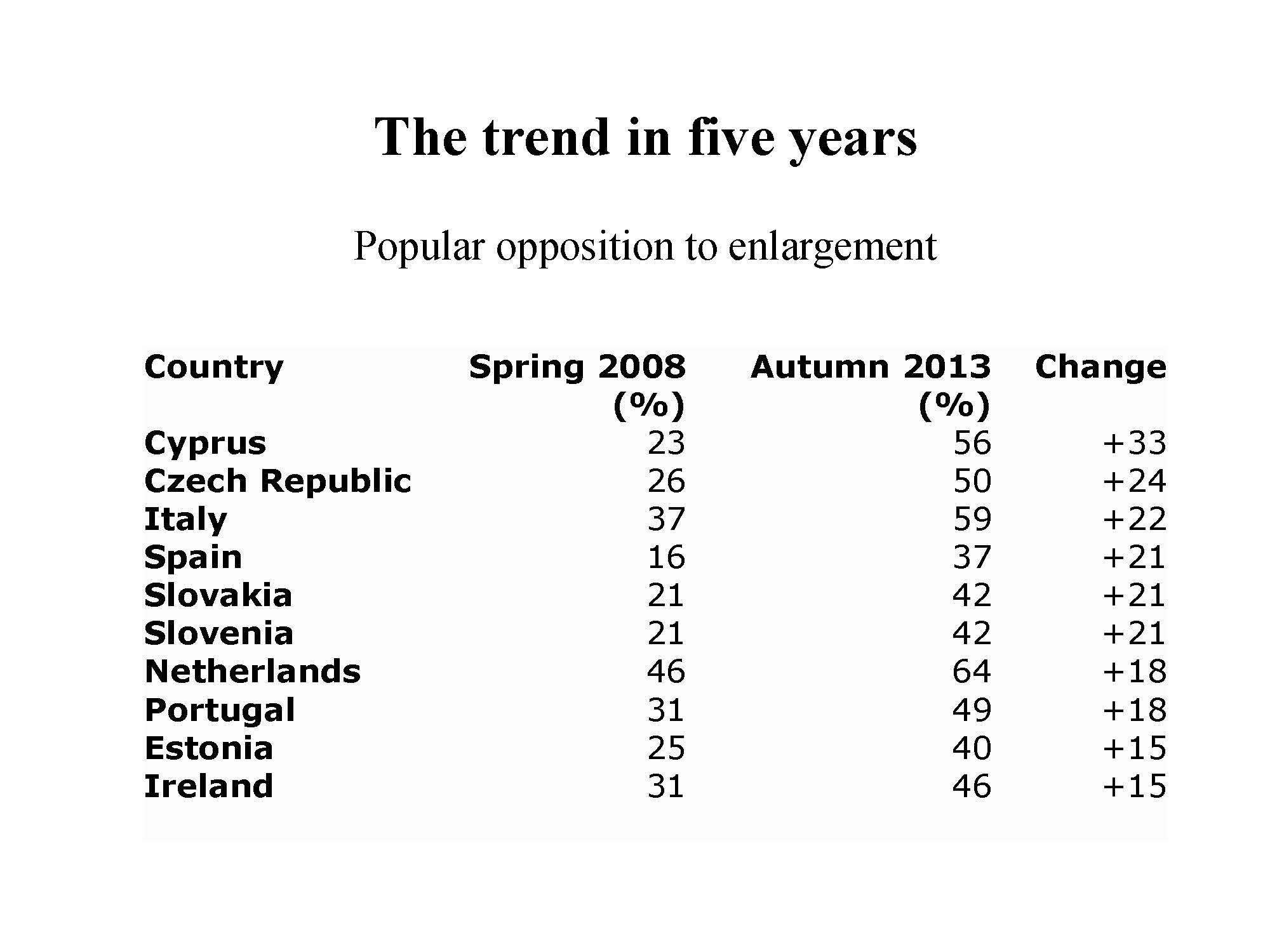

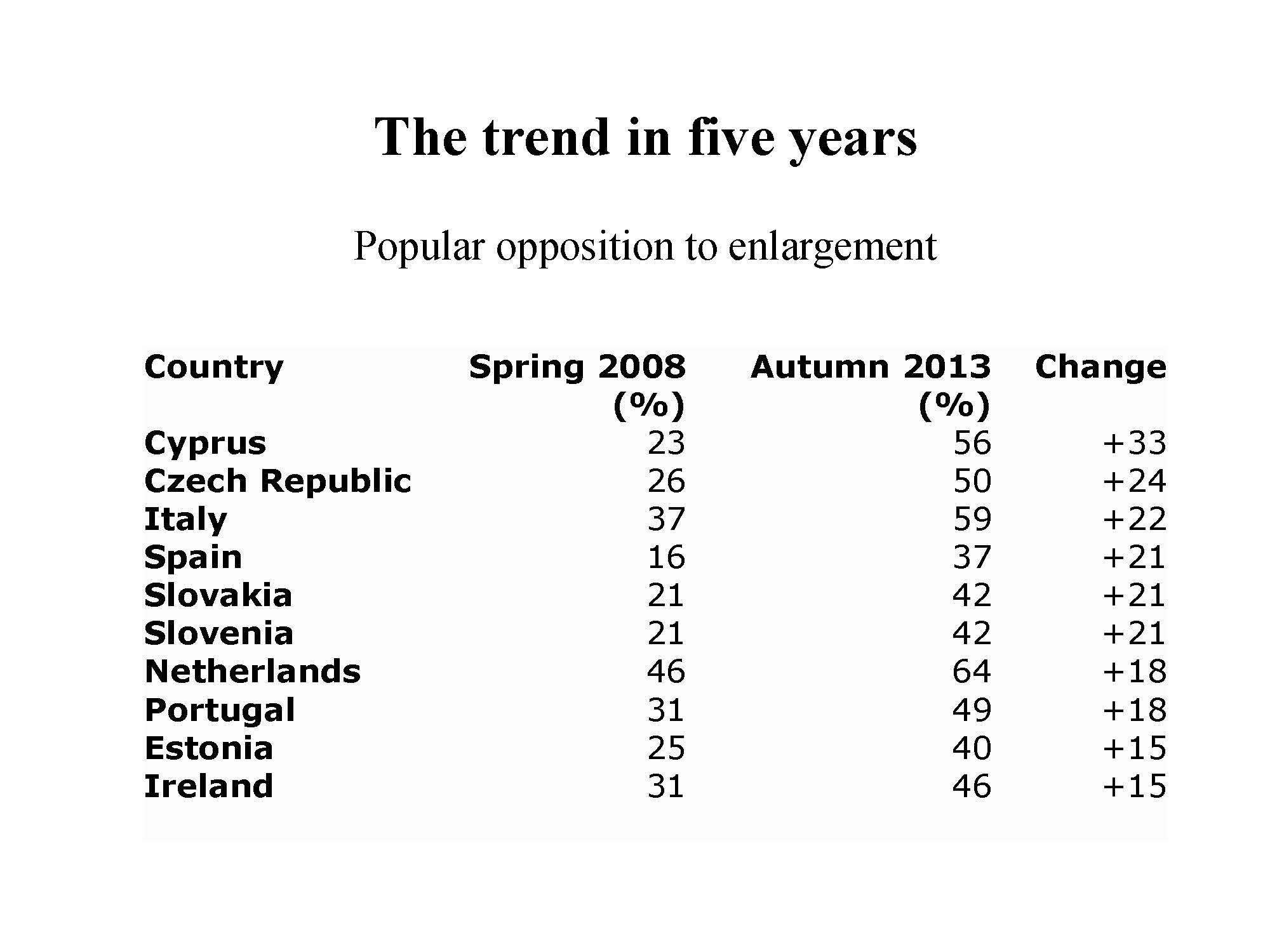

What is even more striking is the overarching TREND in the past five years: a dramatic drop in support across the EU. .

The fall in support for enlargement is sharpest in traditionally pro-enlargement countries such as Italy (where opposition to enlargement increased by 22 percentage points) or Spain (21). Post-2004 EU members, who initially were less sceptical, are rapidly catching up with pre-2004 members. The changes in Cyprus, the Czech Republic and Slovakia are dramatic.

Here opposition to enlargement has increased most since 2008:

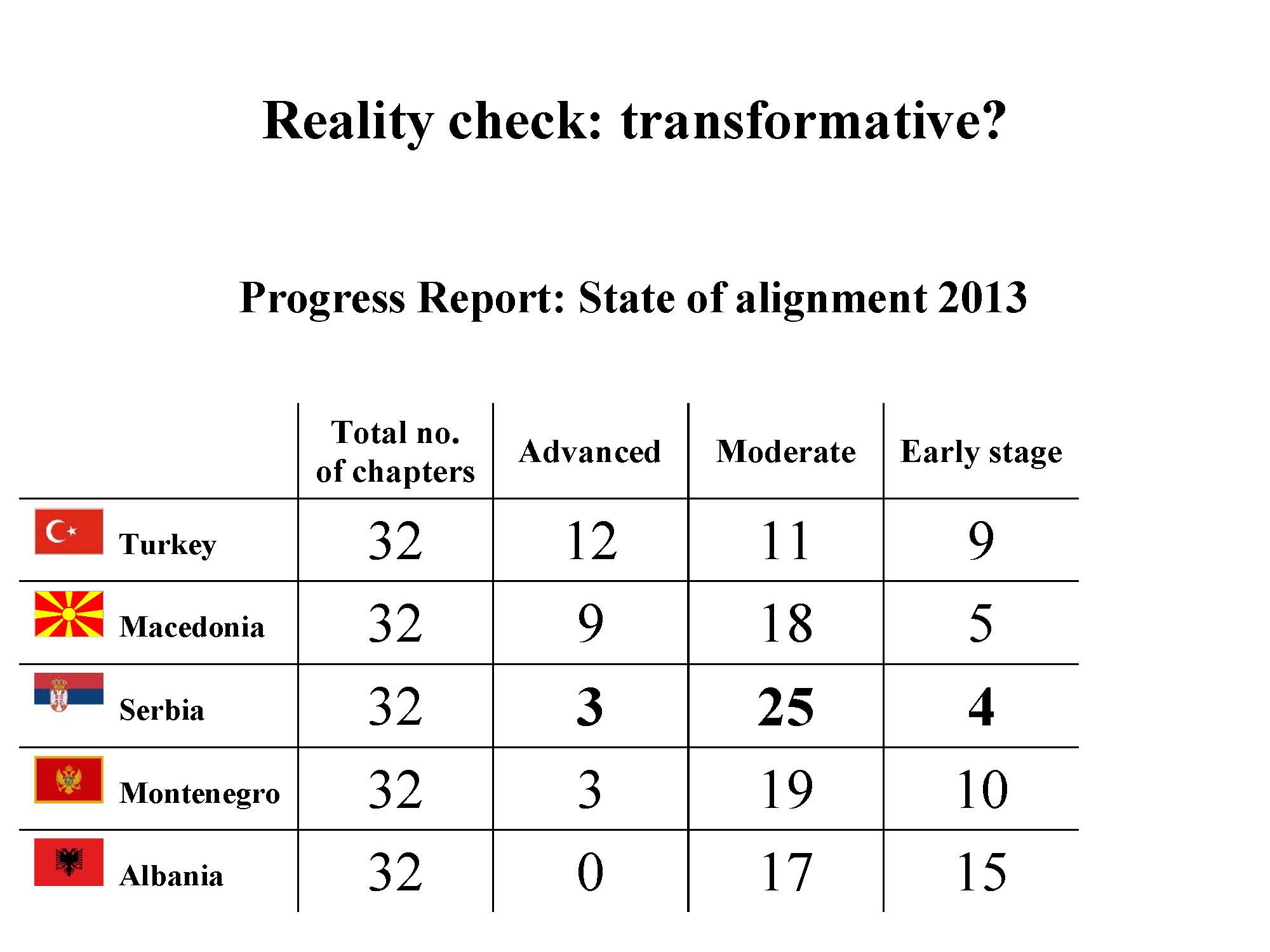

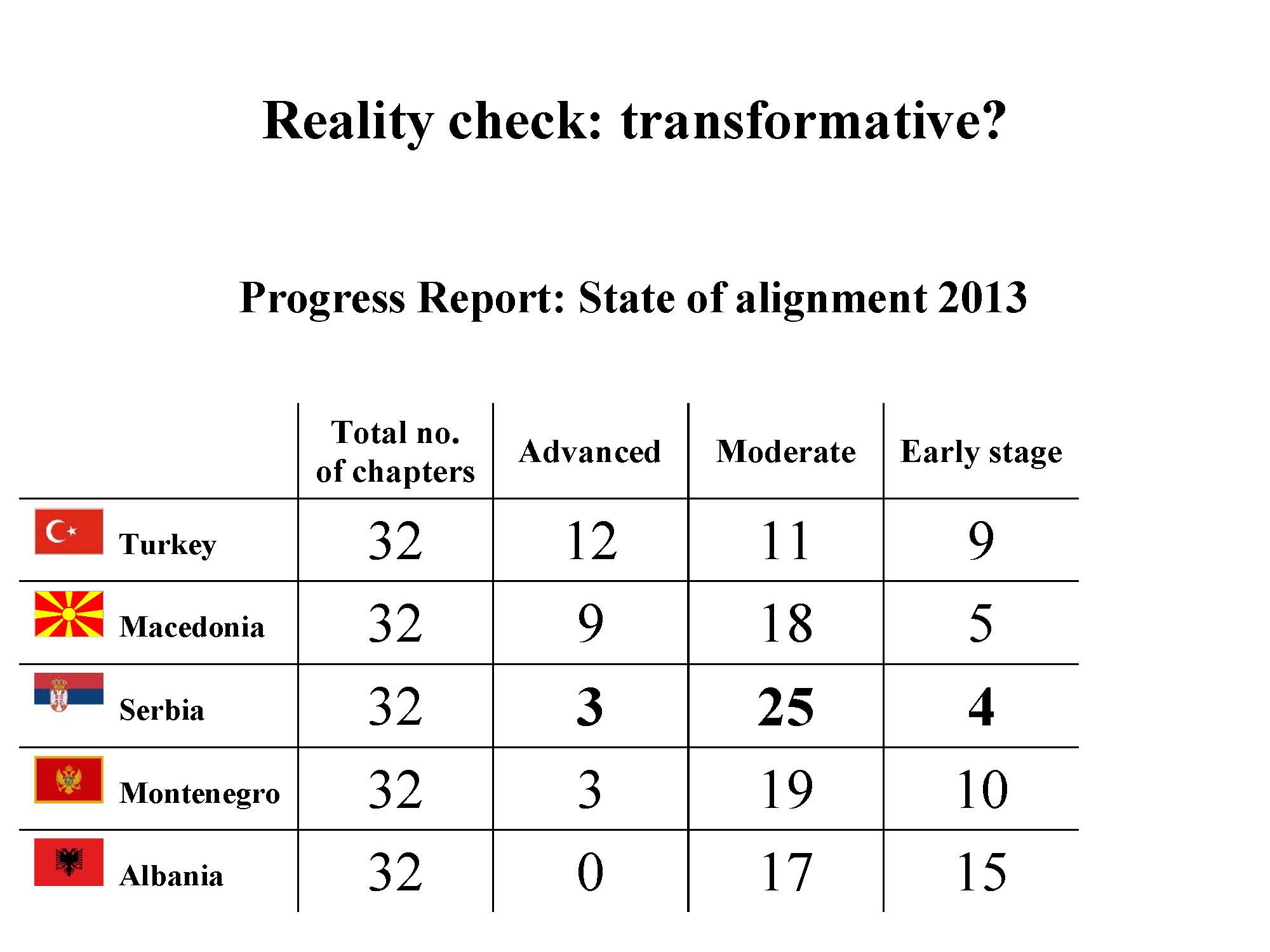

What about the second claim in the opening sentence: that the European Commission has enhanced the TRANSFORMATIVE power of enlargement policy?

Here is a second reality check. Every year the European Commission assesses progress and the state of alignment with EU rules and norms (the acquis) in its annual Progress Reports. It examines for all accession countries whether the alignment in each policy area is “advanced”, “moderate” or at an “early stage.”

Here is what the Commission found in 2013:

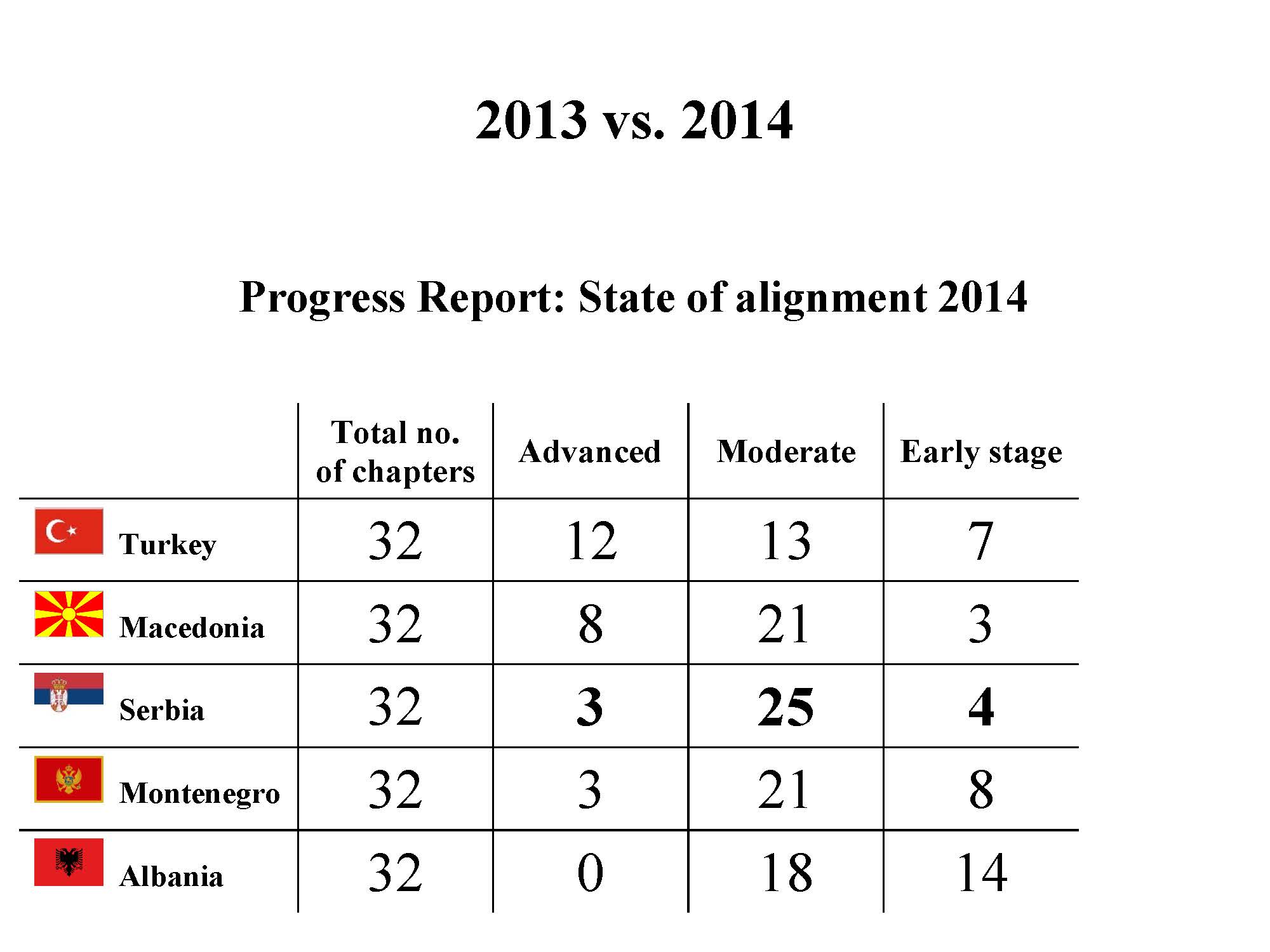

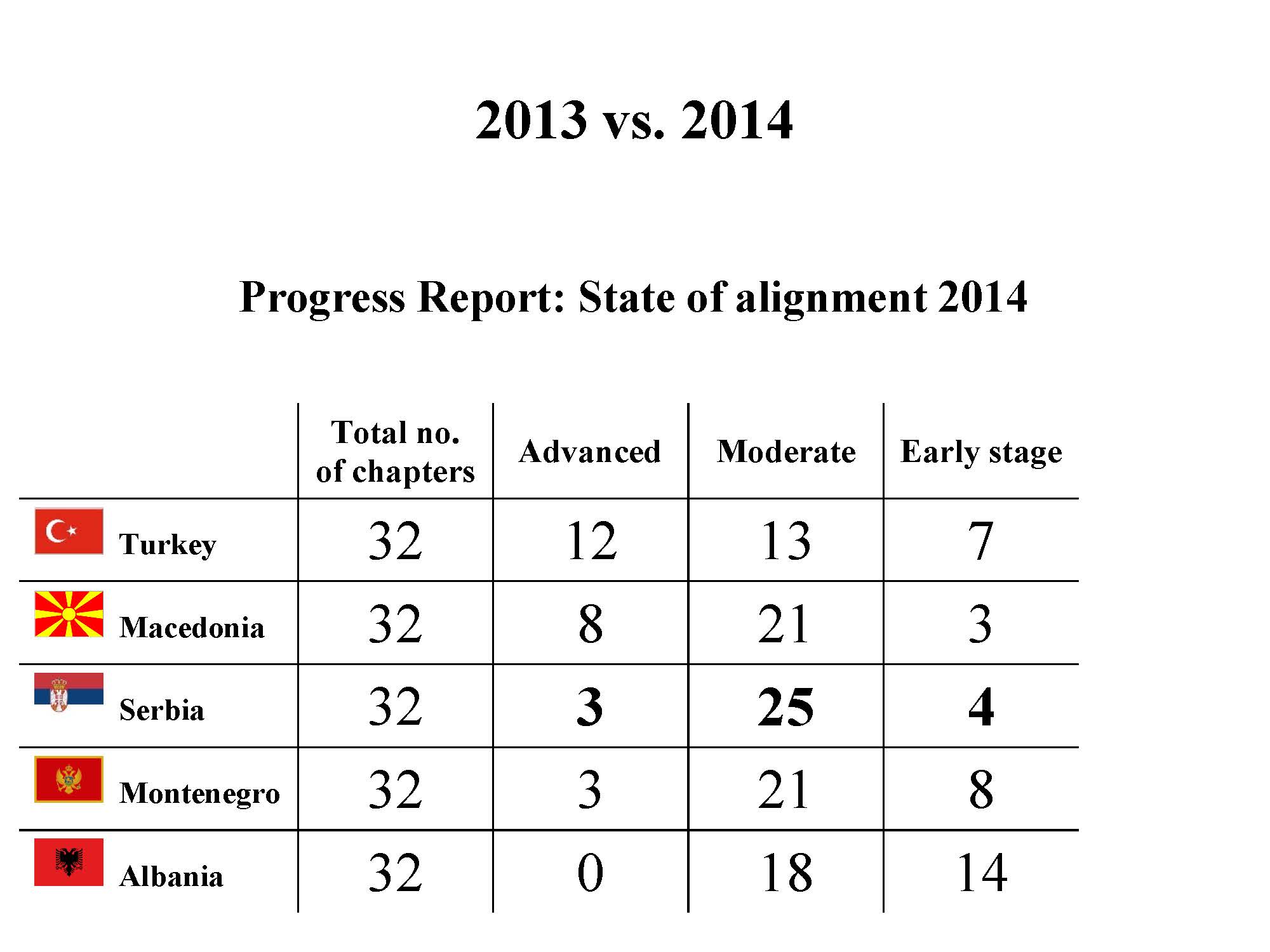

And here is what the European Commission found for 2014:

Comparing these two tables, based on the European Commissions’ own assessment of progress, on the TRANSFORMATIVE impact of the enlargement process, we see the following:

First: there is very little change anywhere.

Second: in the case of Macedonia the Commission finds regression (from 9 to 8 “advanced” chapters).

Third: in the case of Serbia – which also opened accession talks in January – the Commission finds no change at all!

Either the EU process is not actually transformative or the current way in which the European Commission measures transformation in its progress reports is inadequate. Or both. Regardless, the most important documents written by the European Commission to show transformative impact of the enlargement process do not support the sunny view of the Strategy paper.

There is a second striking sentence in the 2014 Enlargement Strategy:

This is a standard claim, made by EU member states and by the European Commission. On 7 June 2014 the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, made a video podcast on Western Balkan enlargement in which she asserted: “There are very clear criteria for the steps needed to move closer to the EU. In the end it is up to each country whether they pass through this process rapidly or not.” The message: “the process is fair. It depends on merit. It depends on you.”

This is a standard claim, made by EU member states and by the European Commission. On 7 June 2014 the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, made a video podcast on Western Balkan enlargement in which she asserted: “There are very clear criteria for the steps needed to move closer to the EU. In the end it is up to each country whether they pass through this process rapidly or not.” The message: “the process is fair. It depends on merit. It depends on you.”

Is this claim convincing?

Look again at the 2014 assessment by the Commission. Macedonia, which became an EU candidate in 2005, is ahead of all other Balkan countries when it comes to its alignment with the acquis according to the European Commission. And yet it is behind Montenegro, Serbia and Albania when it comes to accession. Clearly this is NOT about merit.

Is Macedonia an exceptional case? Hardly. As bilateral vetoes have proliferated, the political nature of every single step in this process has become ever more obvious.

In fact, the problem of merit and fairness goes very deep. Today the accession process is like a stairways with more than 70 steps: to obtain candidate statue, to open accession talks, to open (34 or 35) chapters, to close chapters; then ratification and finally accession. (Note: one could count many more small steps, including the adoption of screening reports, etc …)

For each step up thes estairways there are 28 gatekeepers, EU member states, which have to agree to EACH step taken. And these 28 decide on the basis of political criteria, not merit. Whether Turkey opens Chapter 23, or when and whether Albania, Serbia or Montenegro are allowed to open a chapter, or Macedonia starts accession talks, are all political decisions.

This image captures accession today: a stairways that may well appear to be a stairway to nowhere, given the many veto points and the huge potential for obstruction.

There is one more striking fact about this stairways that renders the current debate on accession puzzling.

Half of these stairs are linked to the “opening of chapters”. In fact, much of the political debate on enlargement today is focused on chapters: how many get opened, and when. But few people – including experts or journalists – ever ask themselves: what is the POINT of “opening a chapter”? What does it mean? What does it do?

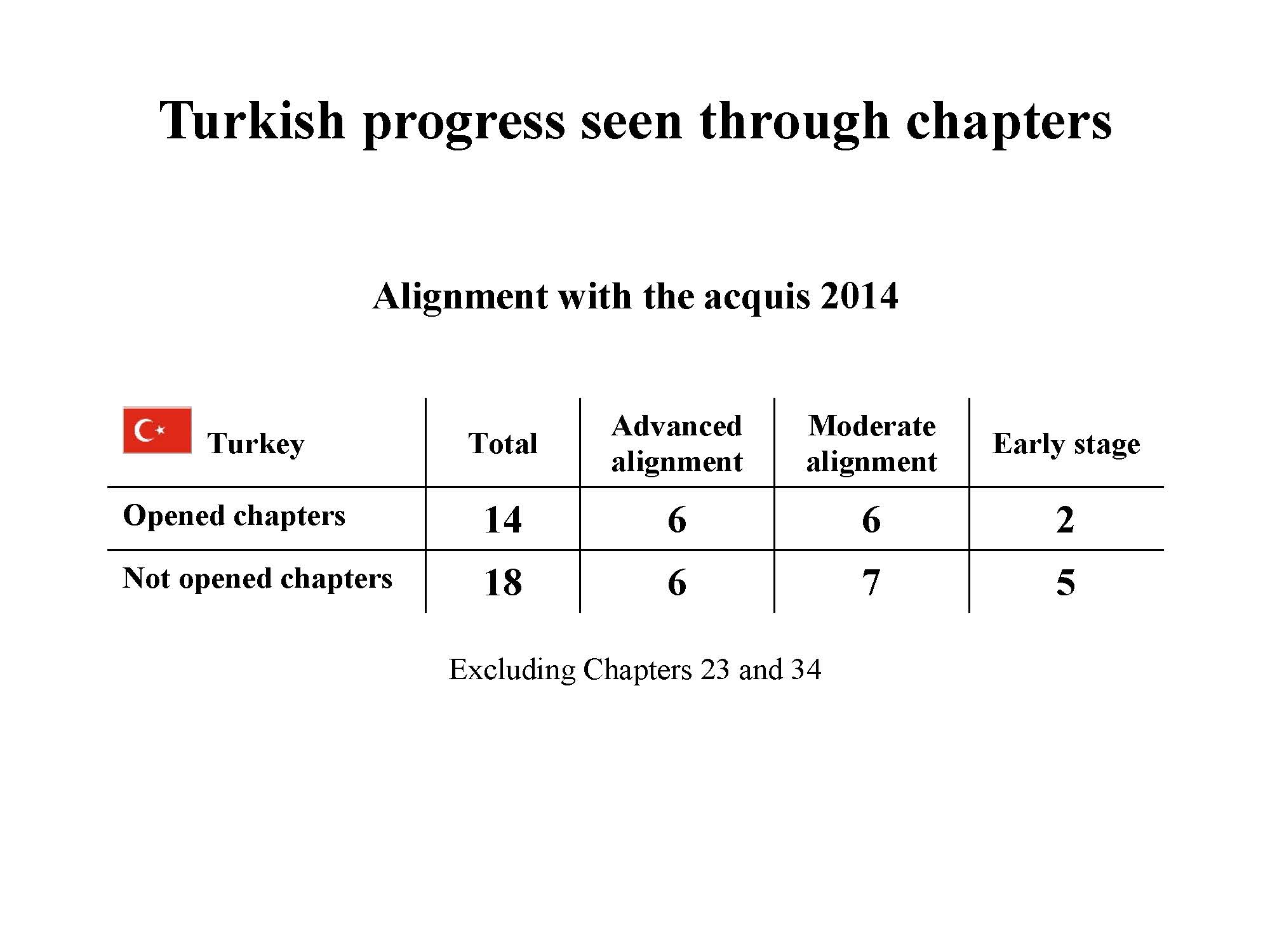

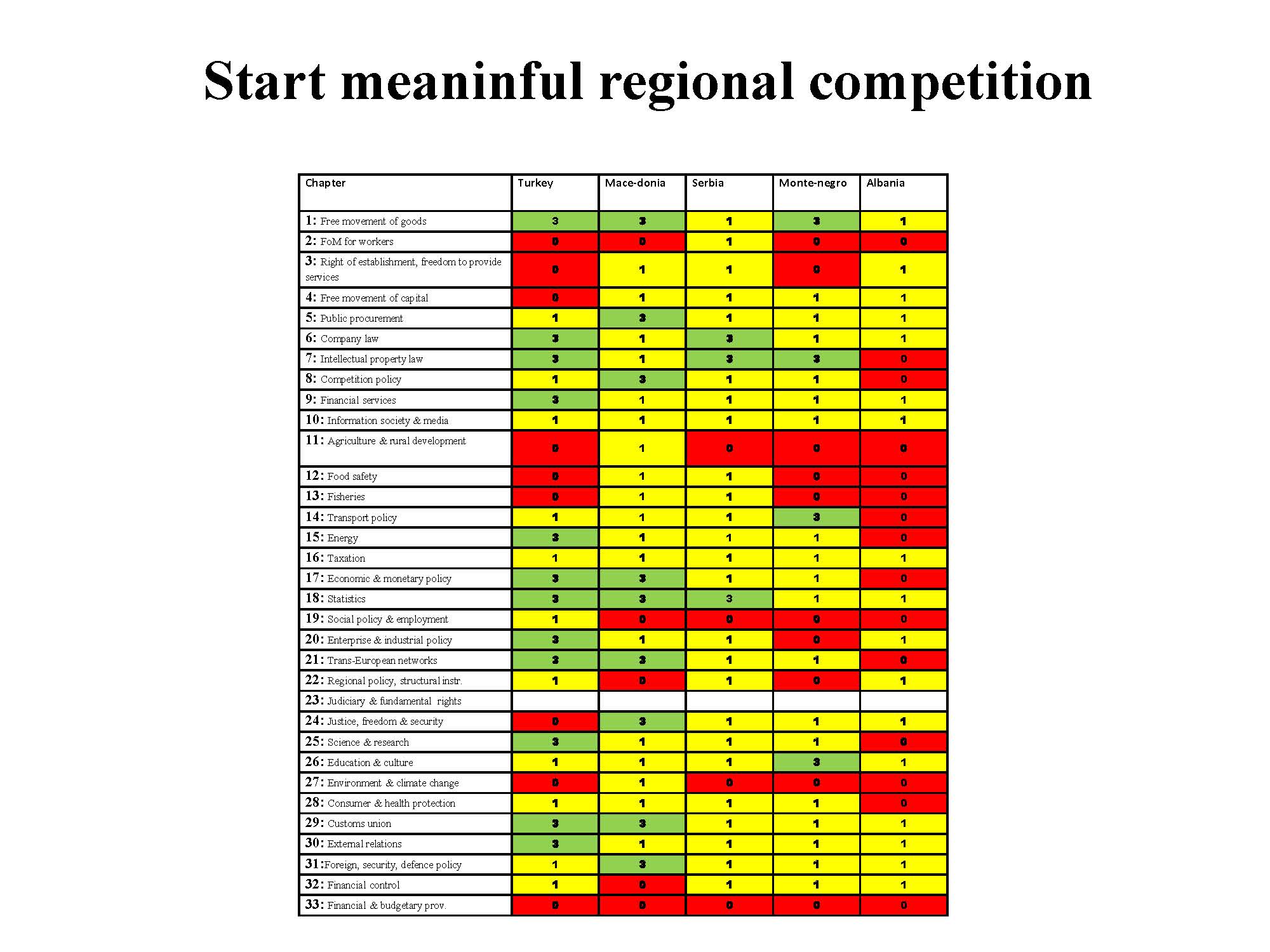

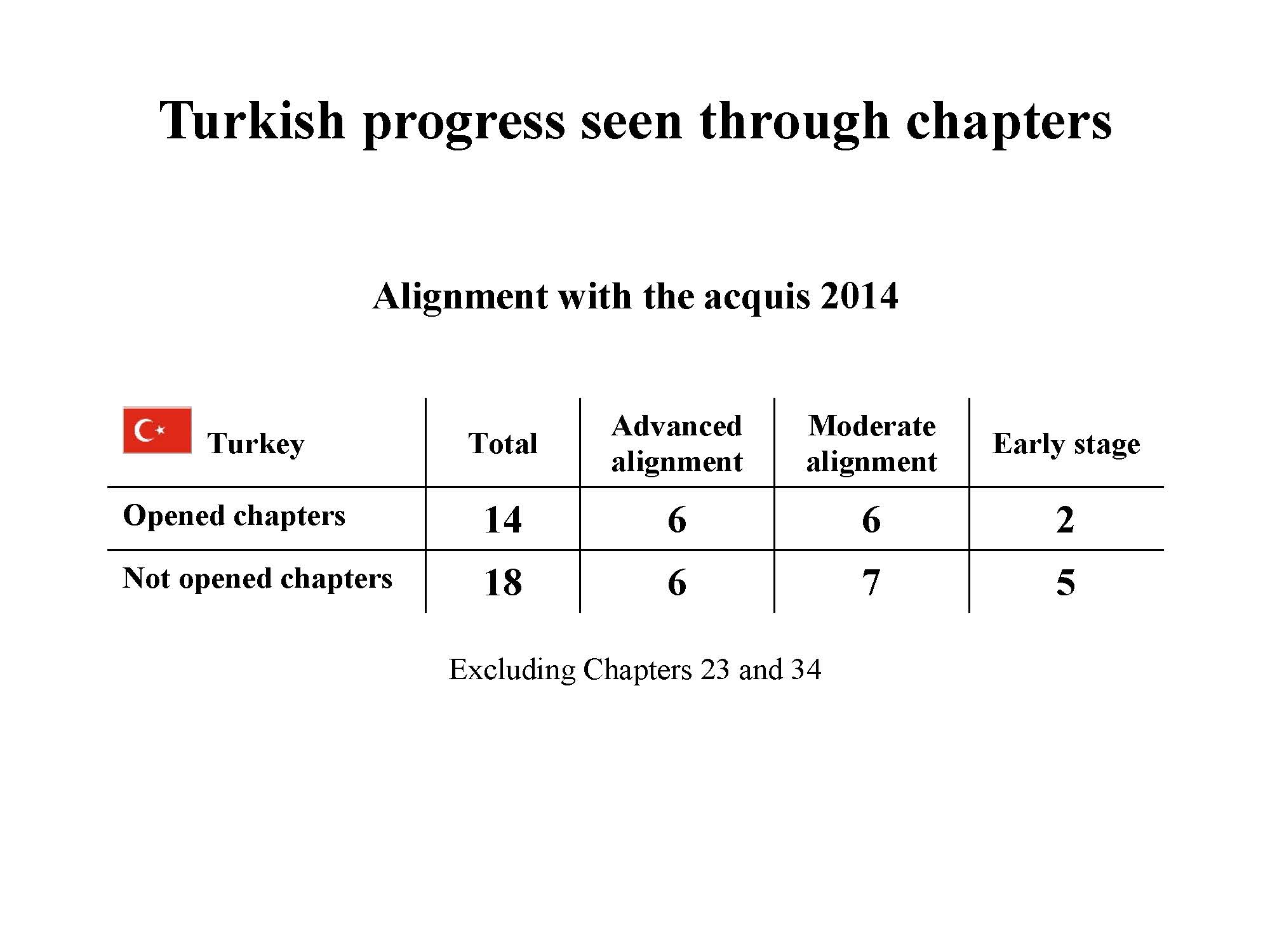

Take the case of Turkey, the most advanced country in its talks, having started in 2005, as an illustration. In 2014 Turkey had 14 open and 18 closed chapters (we leave two chapters, where the Commission provides no assessment of alignment, out of this table here – chapters 23 and 34).

As the following table – based on the Commission’s own assessments in its progress report – shows, there is no causal or other link between the alignment (state of progress) in a sector and whether a chapter is open or closed. This means: whether a country has many or few open chapters is no indicator of where it is in terms of its preparedness for EU accession.

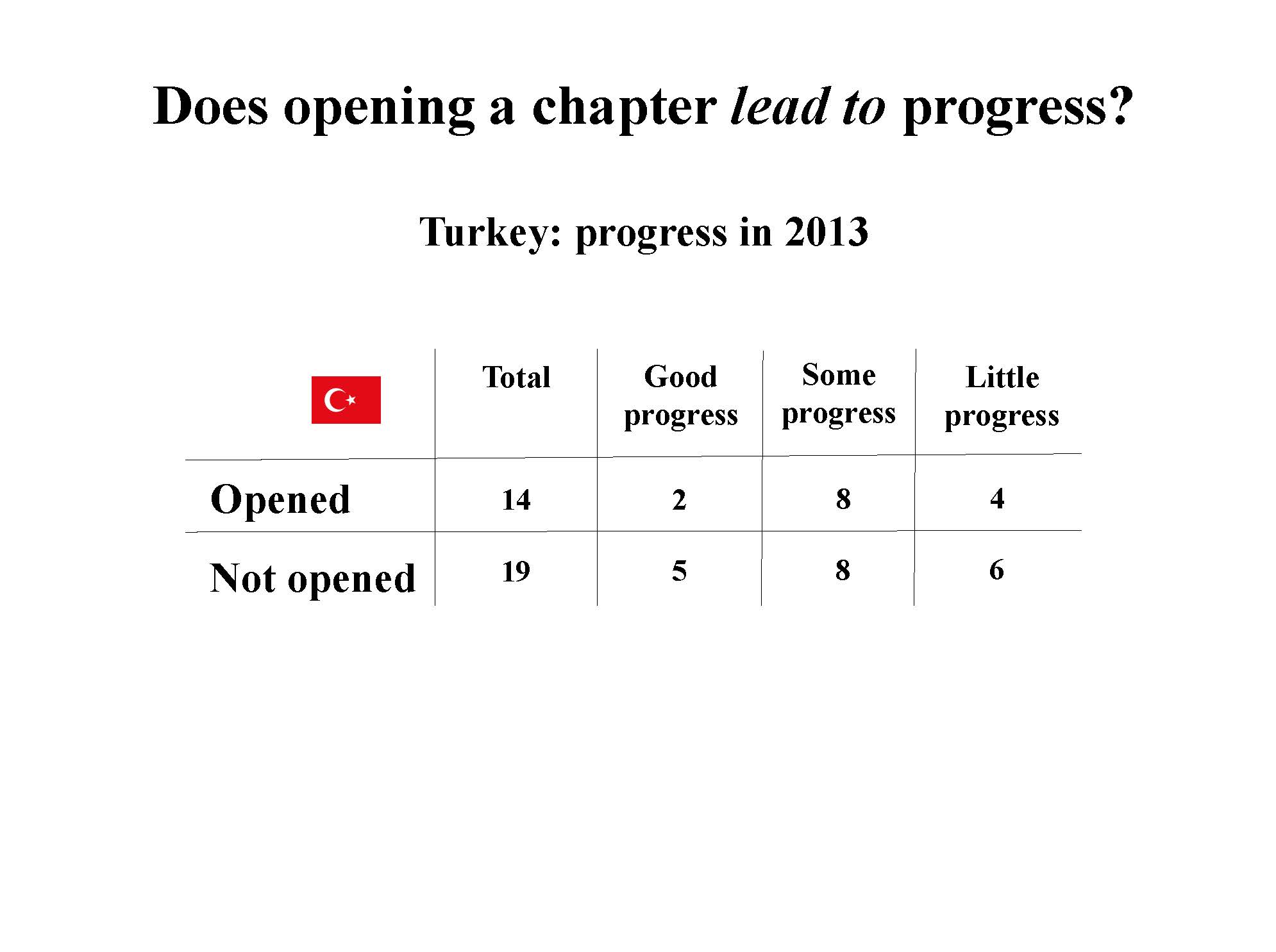

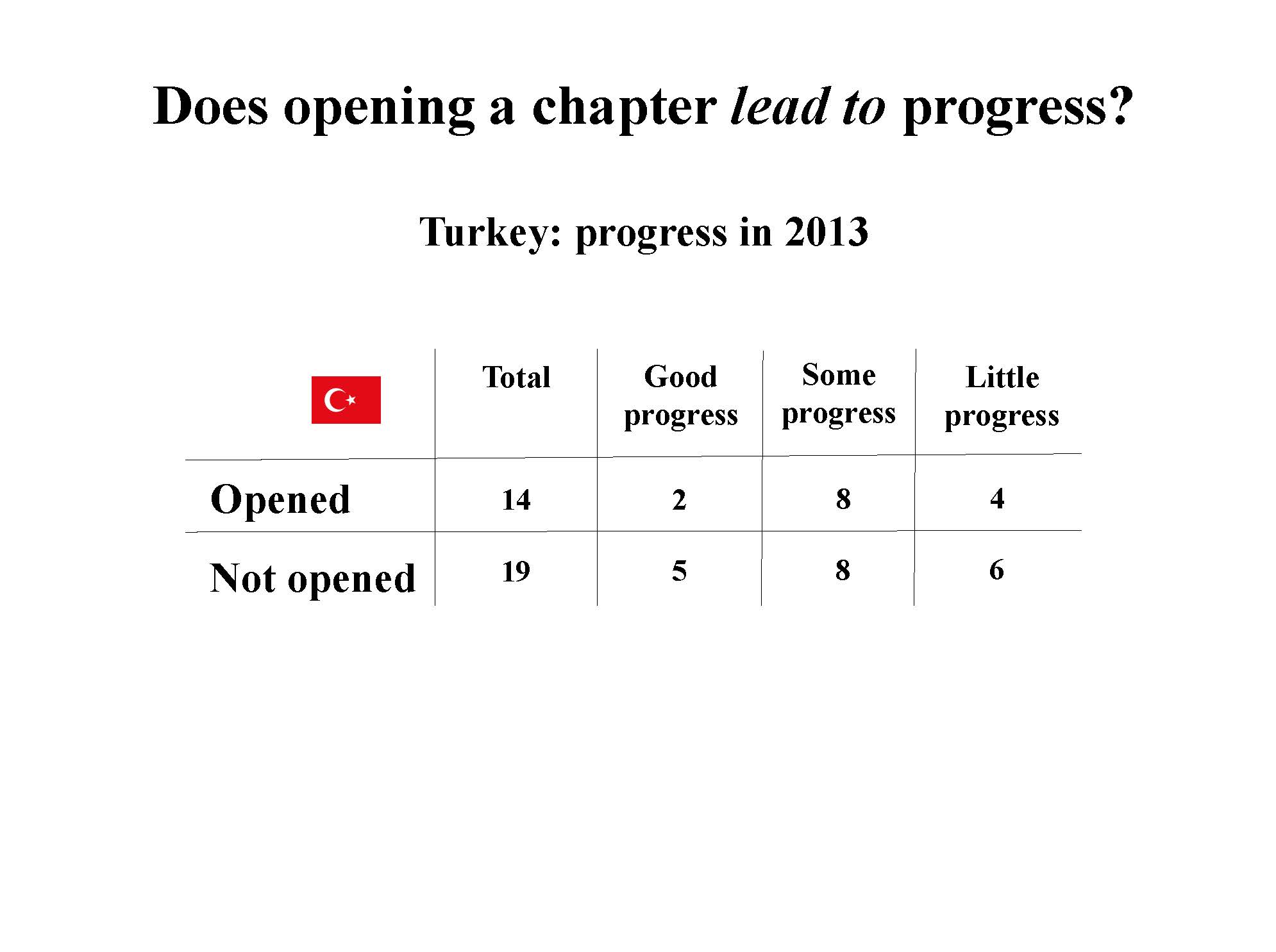

What is no less surprising: opening chapters is not only not a yardstick of progress; it is also not an incentive to make more progress in the future. This is what the European Commission found in Turkey in 2013: there was MORE progress in closed than in open chapters in Turkey during the year.

This raises a basic question: why is it so important to open chapters? Having many open chapters does not indicate progress towards meeeting EU standards. Having many open chapters also does not make future progress more likely.

A recent study of EU-Turkey relations made the following strong recommendation:

“In the light of the above it is stated that opening the chapters Energy (15), Judiciary and Fundamental Rights (23), Justice, Freedoms and Security (24) and Foreign, Security and Defense Policies (31) would facilitate Turkey’s drawing a robust road map under the EU umbrella at a time when the country faces three successive elections.”

This is the conventional wisdom, repeated in conference after conference, article after article. However, it is not explained HOW opening a chapter is crucial for either the EU or for Turkey; why a Turkish citizen, or a sceptical EU member state parliamentarian, should consider this significant.

In summer 2013 there was a heated debate in Turkey and in the EU whether to open a new chapter after many year in which none were opened: Chapter 22 (regional policy). There were many statements by politicians about how important this would be. Egemen Bagis, Turkey’s chief negotiator, explained in April 2013:

“Since no new chapter has been opened, I have kindly asked our prime minister to slow down everything until a new chapter is opened. I thank him for having done that. Now the process for the opening of the regional policies chapter has begun.”

Foreign minister Ahmet Davutoglu stated:

“No postponement or review of the decision to open it is possible. As we said before during the reform follow-up group meeting, we want not only the chapter 22 to open but also the chapters 23 and 24.”

The German government, on the other hand, insisted on delaying the opening until after summer 2013. In the end chapter 22 was formally opened in the autumn. Leaders – and international media – spoke about this as if something significant had happened (Die Welt: “Accession talks gain new momentum”)

In fact, following a meeting – the so-called Intergovernmental Conference – when it was declared that Chapter 22 was now “open”, nothing else happened. There was no additional meeting. There was no additional funding. There was no additional impetus for reform. The “opening” was political theater, for one day. It had no link to merit, criteria, or progress. Ultimately it made no difference.

We can now easily understand how all these dynamics create a deeply frustrating and dysfunctional process.

In the face of growing public opposition, many EU leaders have given up defending enlargement policy. Seen from Brussels, Berlin, Paris or The Hague, the current group of candidates are problematic. They are poorer, have weaker institutions and are more politically polarised than any previous group of applicants. This has created a vicious cycle. As enlargement loses popularity in EU member states, EU leaders try to reassure their voters that the process is stricter than ever. Yet as the hurdles to be jumped appear more and more arbitrary, candidate countries find it harder to take difficult decisions in pursuit of a goal that is increasingly distant and uncertain. The stairways approach makes vetoes extremely easy. And the public debate is focused on whether chapters are open or closed, not on whether reforms are taking place.

This is not enlargement “fatigue”, suggesting a temporary state of exhaustion. It is a chronic ailment, which is getting worse.

And at the heart of this frustration are the annual Progress Reports. As ESI found, discussing these in many European capitals during the past year, few people, even EU foreign ministry officials, read these carefully. The reports are not doing a convincing job measuring progress. They do not allow for comparisons between countries in any operationally meaningful detail. They do not educate the public about what needs to happen. Above all they do not make real transformation – if it happens – visible also to sceptics. It is as if everyone – reformers in candidate countries, publics, policy makers in the EU – is proceeding through thick fog.

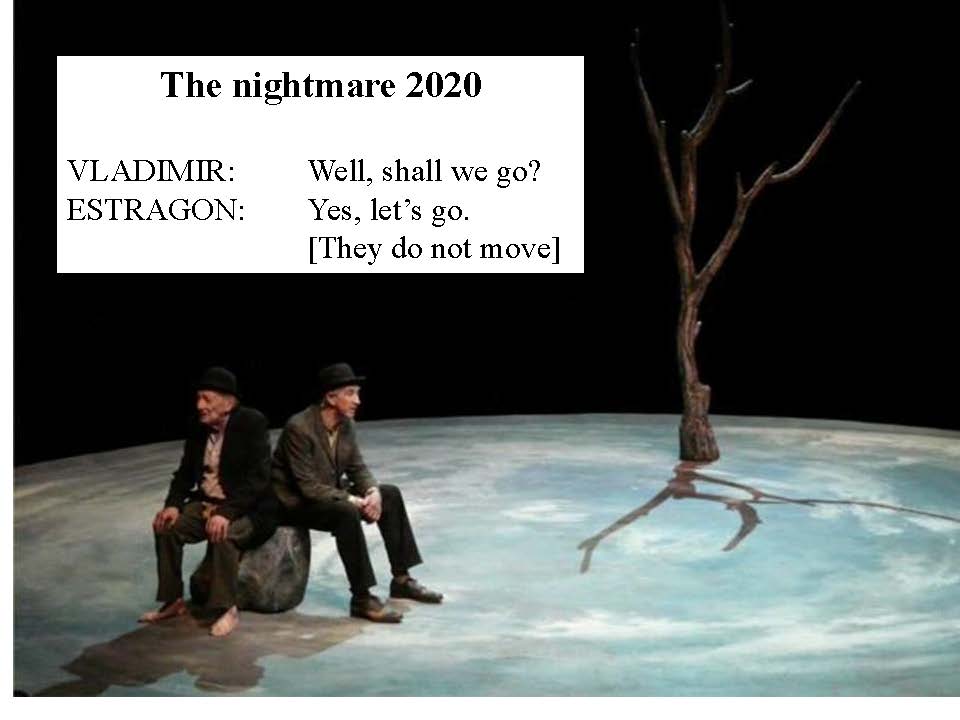

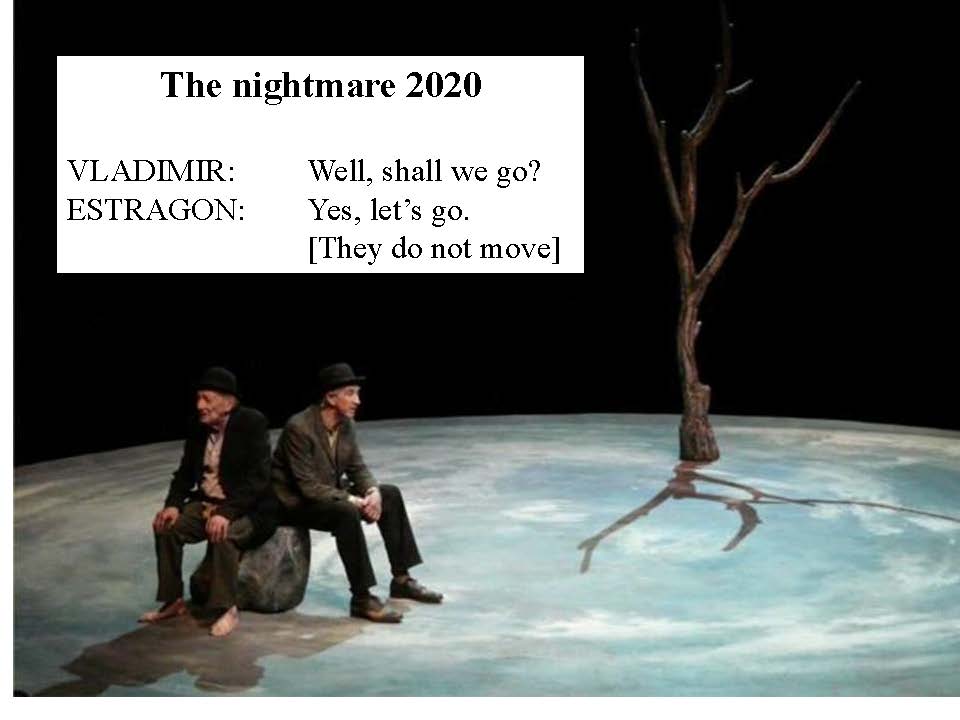

Such a proces increases frustrations. We have called this the Godot effect. It is today most pronounced in Macedonia and Turkey. However, unless the process change we may anticipate that something similar could soon happen in Montenegro, Serbia and Albania, as cynicism increases. In Bosnia and Kosovo, there is today frustration, cynicism and apathy before any EU accession process has even begun. Bosnia has not yet applied for accession. Kosovo is not even able to apply.

So what is to be done? In order to answer this question let us imagine a very different approach to defining and assessing progress; one that is strict, fair and transparent. A process as follows:

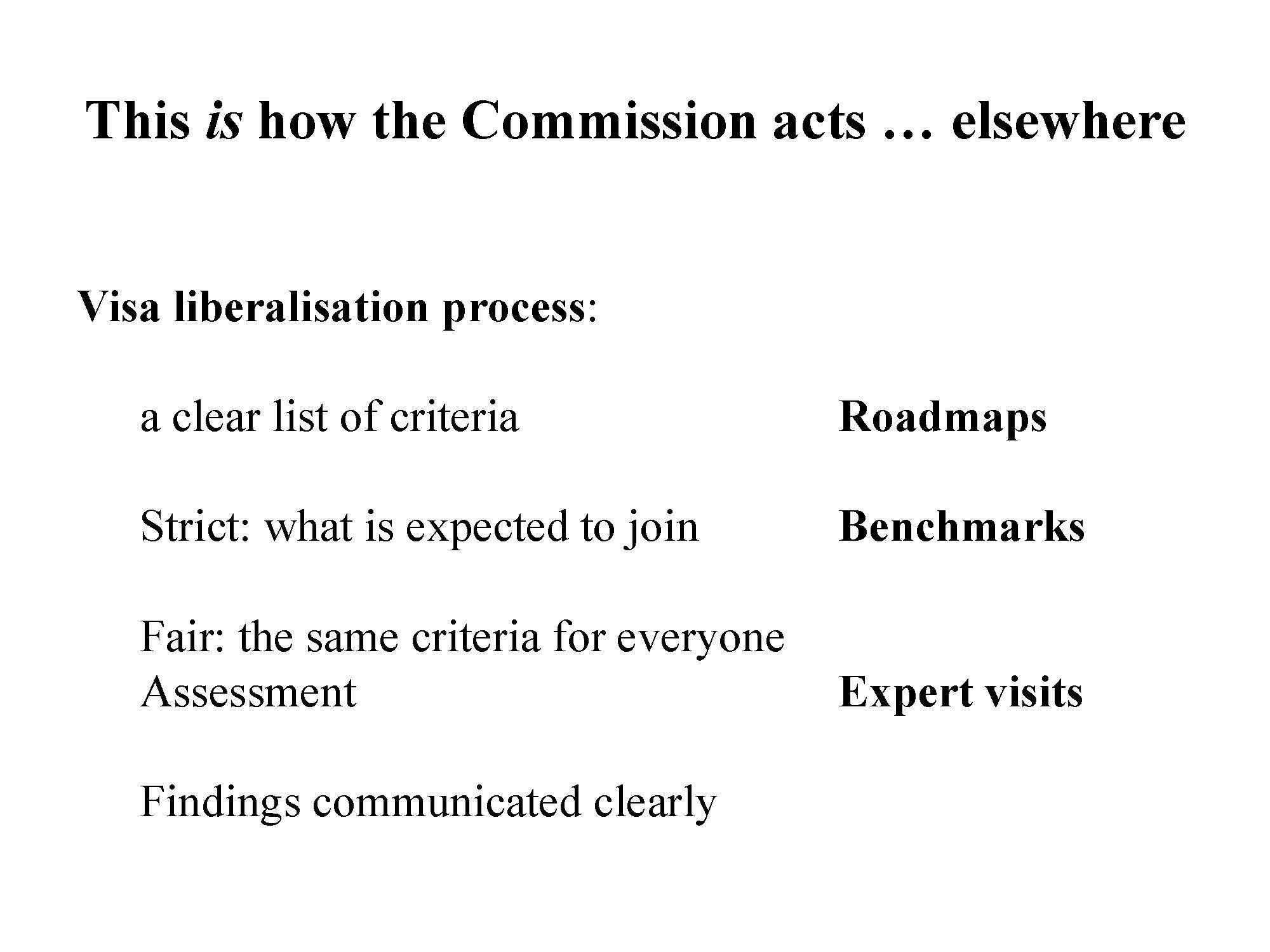

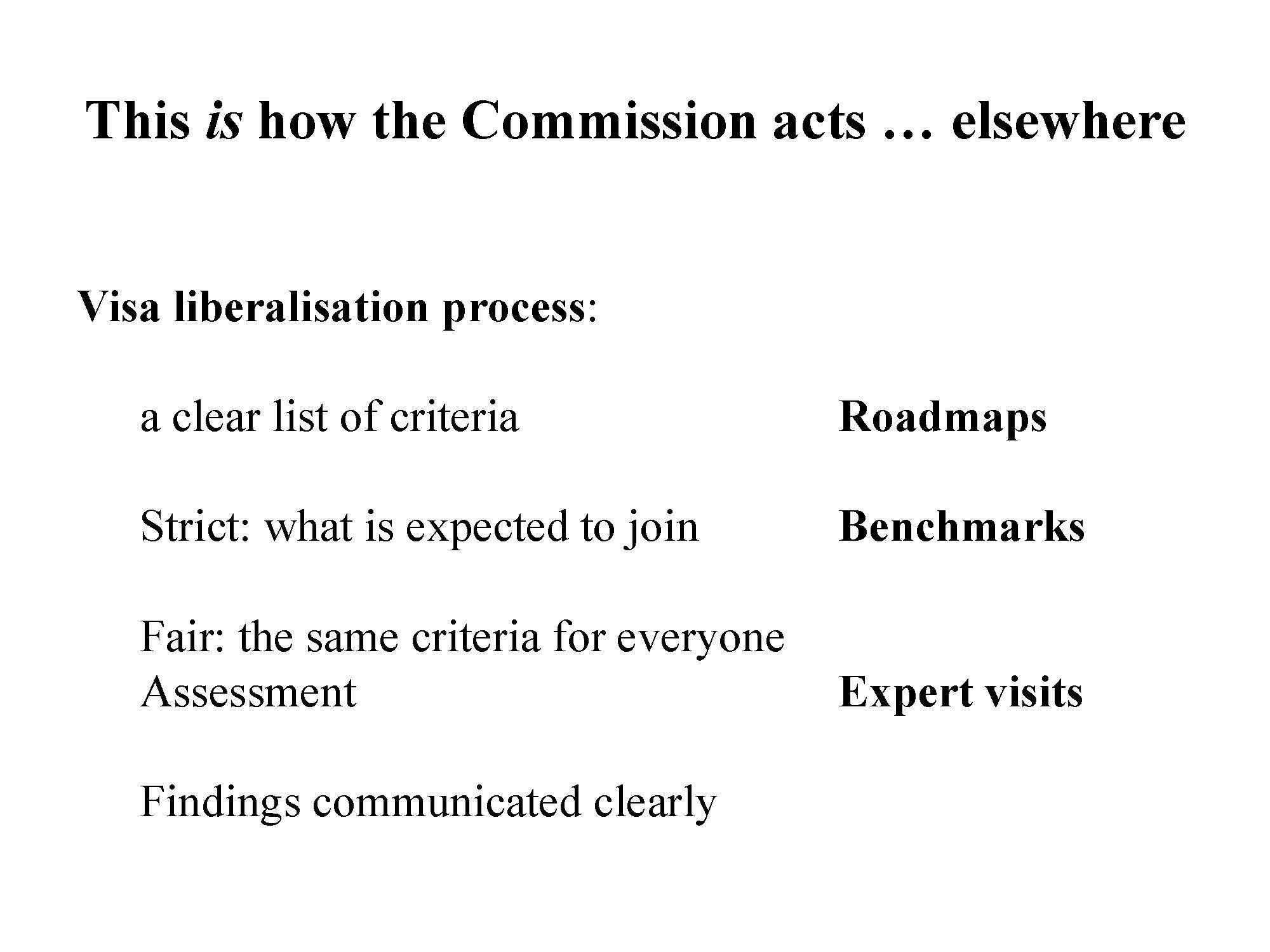

To imagine such a process is not to daydream. For this is how the Commission has acted for years in the context of visa liberalisation.

In this crucial area ALL countries in the Balkans were given precise visa roadmaps with dozens of benchmarks. These roadmaps set out clearly what the Commission expected. They listed all individual criteria. There were no short cuts. And these roadmps, based on the acquis, were essentially the same for all countries, and thus progress easily compared.

The Commission then organised a serious monitoring and assessment effort. This involved experts from the Commission and from member states. Based on their findings detailed progress assessments were issued.

The whole process was developed by the Directorate General for Home Affairs together with the Directorate General for Enlargement. And it worked. It inspired many reforms. It made it possible to see where real reforms happened … and when they did not. Above all it convinced even sceptical EU interior ministers that when the Commission did find progress they could trust it.

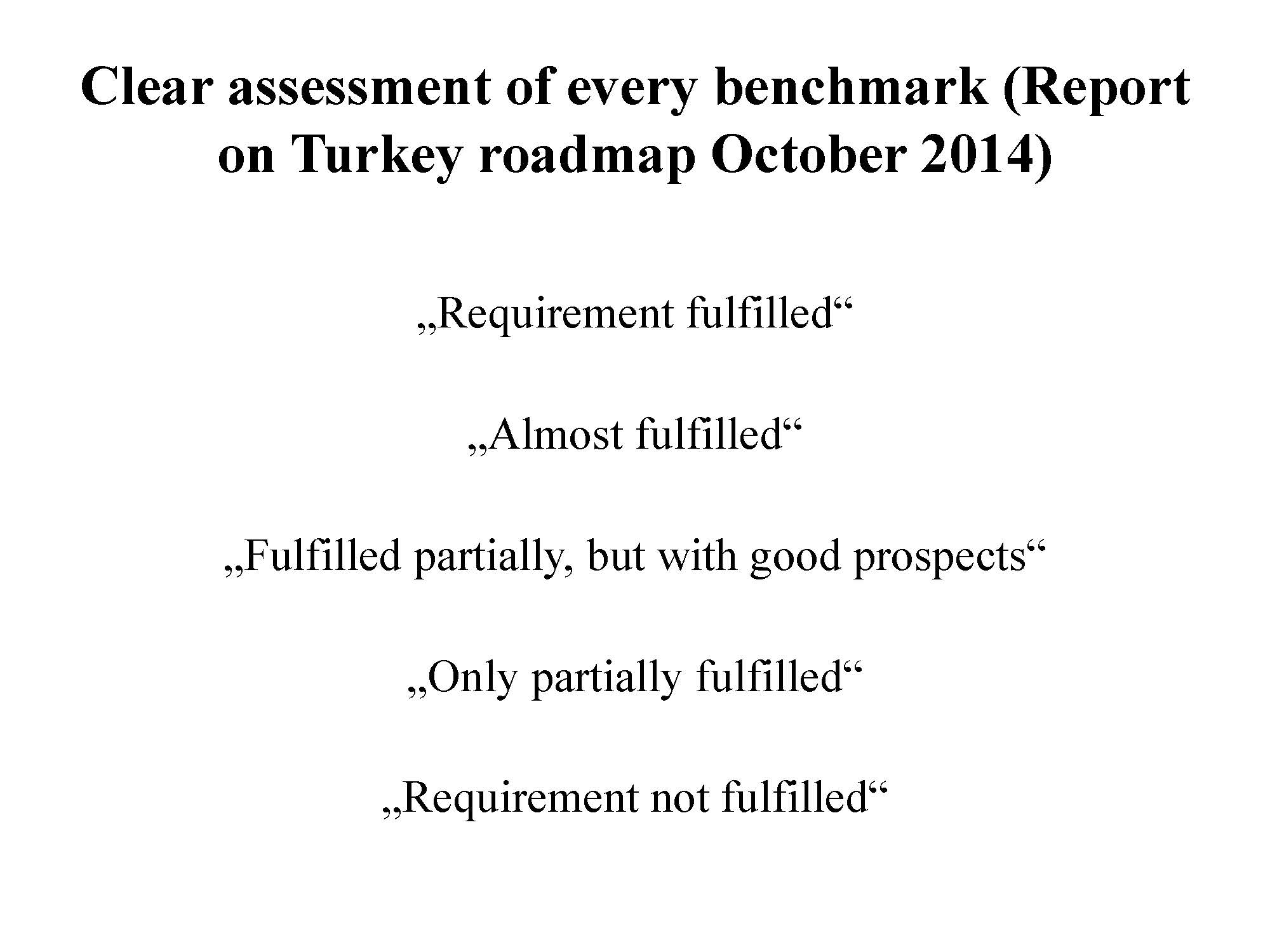

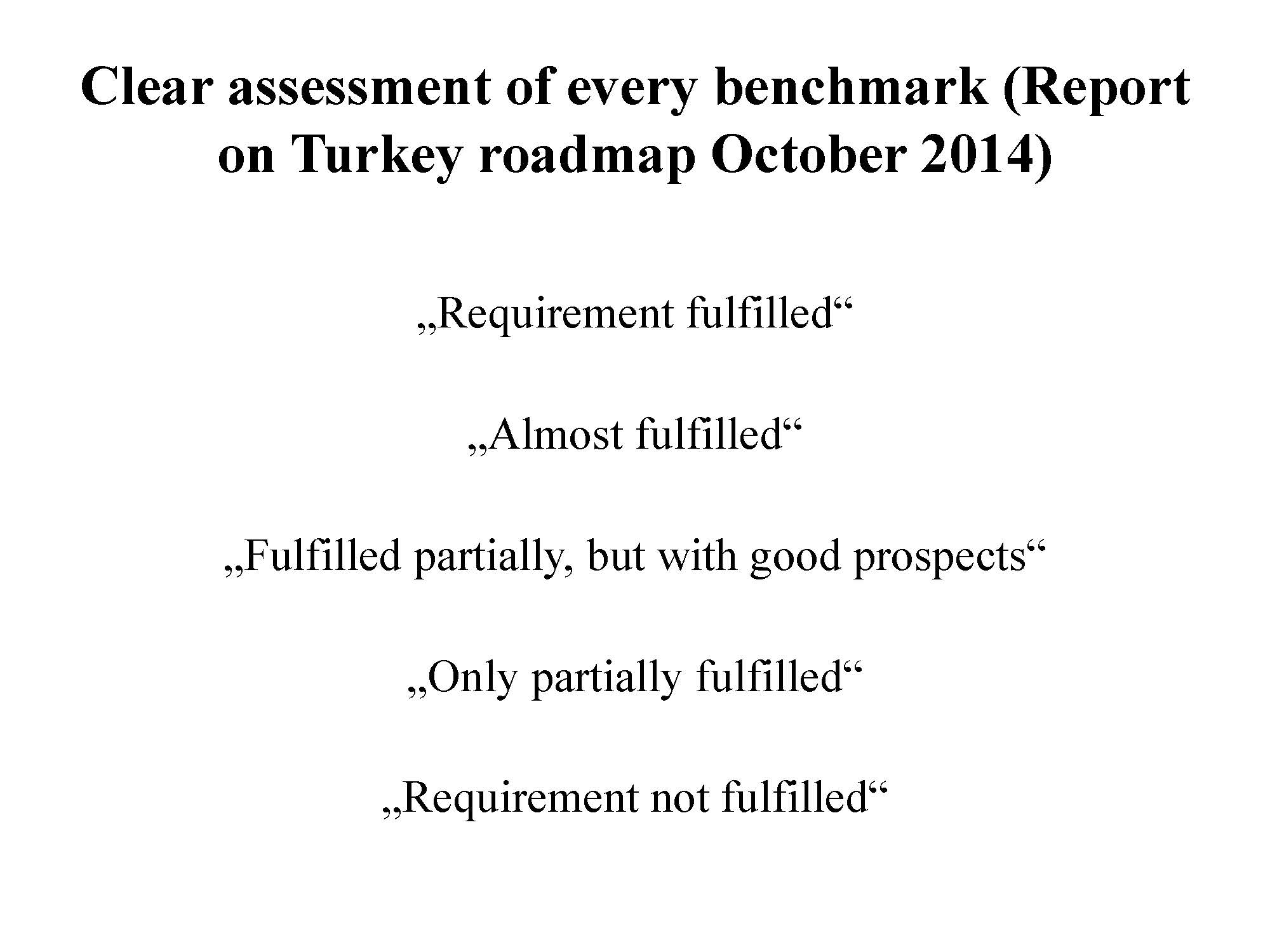

In fact, in October 2014, while DG enlargement published its regular progress reports, another part of the Commission also published a detailed document on progress made in the field of visa liberalisation by Turkey. It offers a clear, readable, strict and fair description of where Turkey stands. Each benchmark is assessed, using the following categories:

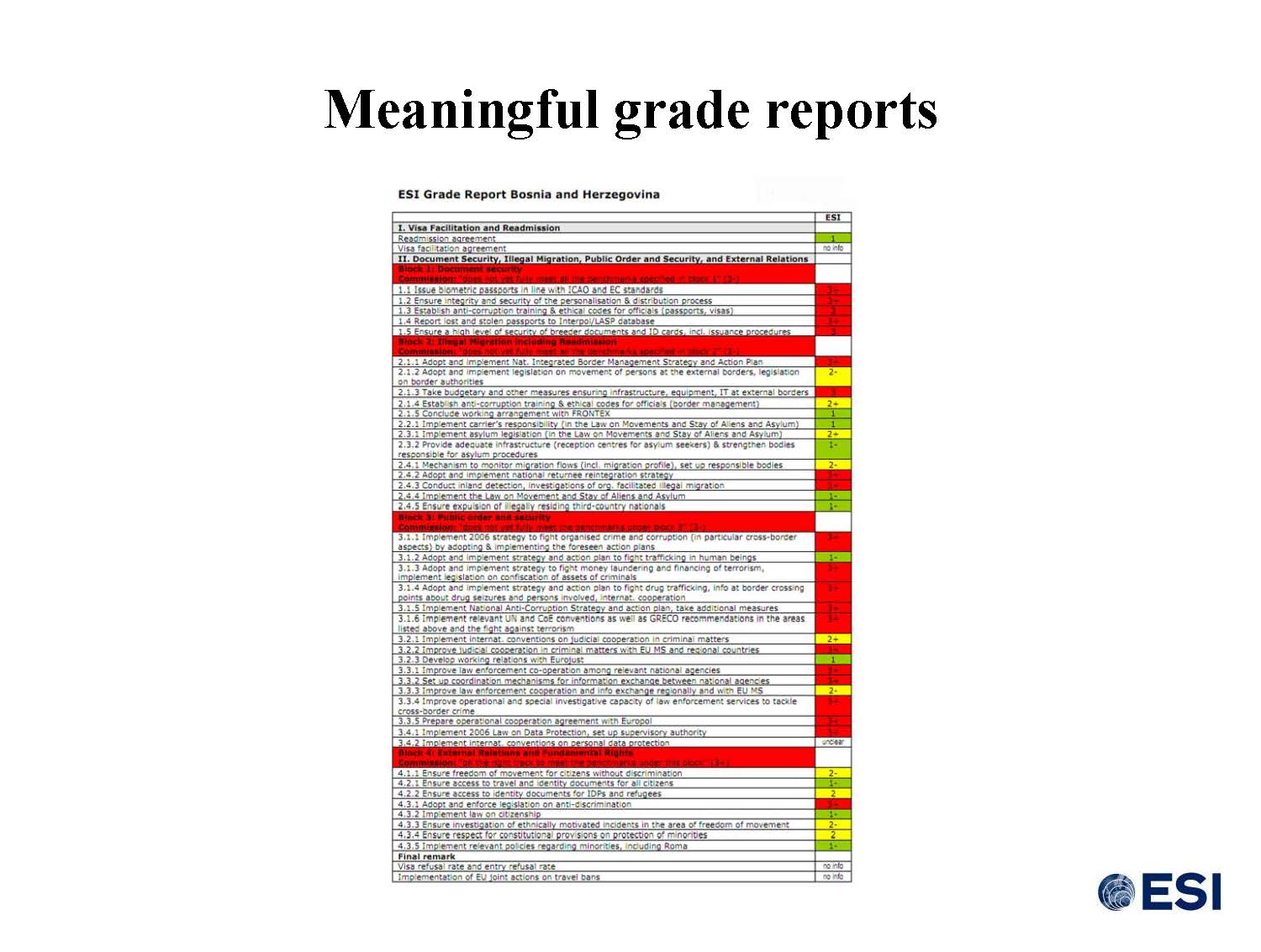

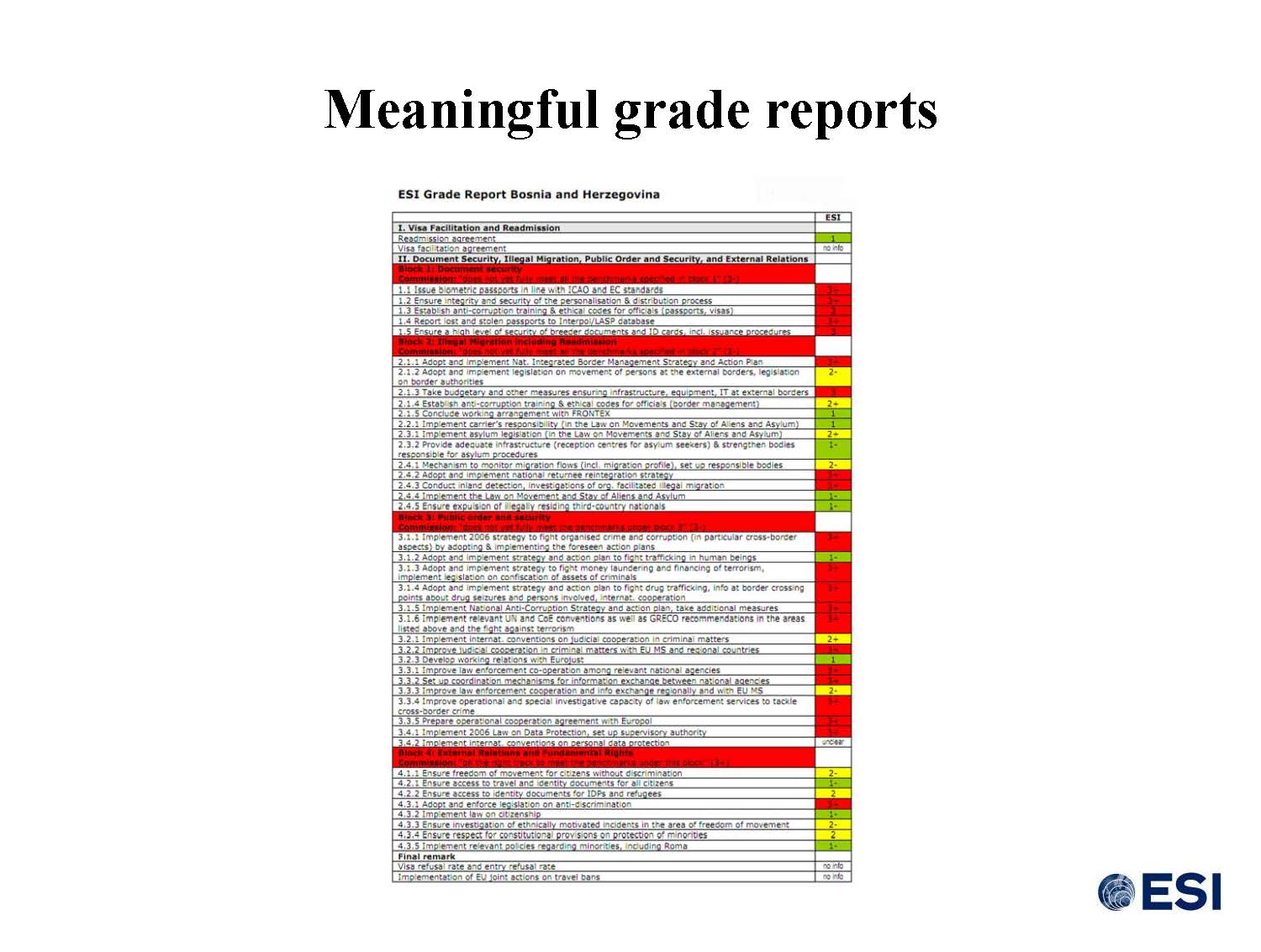

The result of such a strict, fair, and meritocratic process in the case of the Western Balkans was to inspire civil servants. It was also clear to them what needed to be done. All countries were assessed based on the same criteria. It was possible to make transformations visible; even in special grade reports, that ESI issued at the time, based on the Commission experts’ assessments:

We can compare the thoroughness of this process with the current assessment of progress in key chapters in the Progress Reports. Let us take just one subject, Chapter 18 (Statistics).

Look at the current assessment of progress in the field of statistics in Turkey, which has been in this process the longest. In 2014 the European Commission published just four short paragraphs, about half a page, on this chapter in the Turkey progress report. A reader does not understand from this how far Turkey has come, what remains to be done to reach EU standards, or in what specific areas most efforts are still needed. Nor can one see how Turkey compares to other candidates.

This is surprising for many reasons:

1. The recent experience with Greece. Following the discovery of just how unreliable key statistics provided by the National Statistical Service of Greece (NSSG) had been before 2010, a new statistical agency, ELSTAT, was created. This was a priority for reform for the EU!

One might expect the EU to be just as keen to see all Balkan countries reach EU standards for all their key statistics, as soon as possible, and well before actually joining the EU, in order to be able to develop a credible track record.

2. The importance given to “economic governance” in the accession process. Without reliable economic statistics, from GDP per capita to employment, from the FDI stock to exports, discussions of economic governance in progress reports are of little use; and any evidence-based policy making on the part of governments is very hard.

3. One objective of the annual progress reports is to assess whether a country is a “functioning market economy” or FU-MAR-E. How can this be done without comparable and solid numbers and statistics?

The sooner all accession countries reach EU standards in the field of statistics the better. Now imagine a scenario where the European Commission draws up a roadmap for Chapter 18, gives it to every country, and thus spells out what all the key benchmarks for a future EU member are … and then assesses the state of affairs against these benchmarks every year with the help of experts, in order to produce a document on statistics that is similar to the recent October report the Commission produced for the Council and the European Parliament on visa liberalisation.

The current EU accession process has not halted the erosion of trust in the policy since 2008. It has not led to measurable transformative impact in key policy areas. The visa roadmap process, on the other hand, has inspired and encouraged change. It has also – crucially – made this change visible and credible to sceptical outsiders.

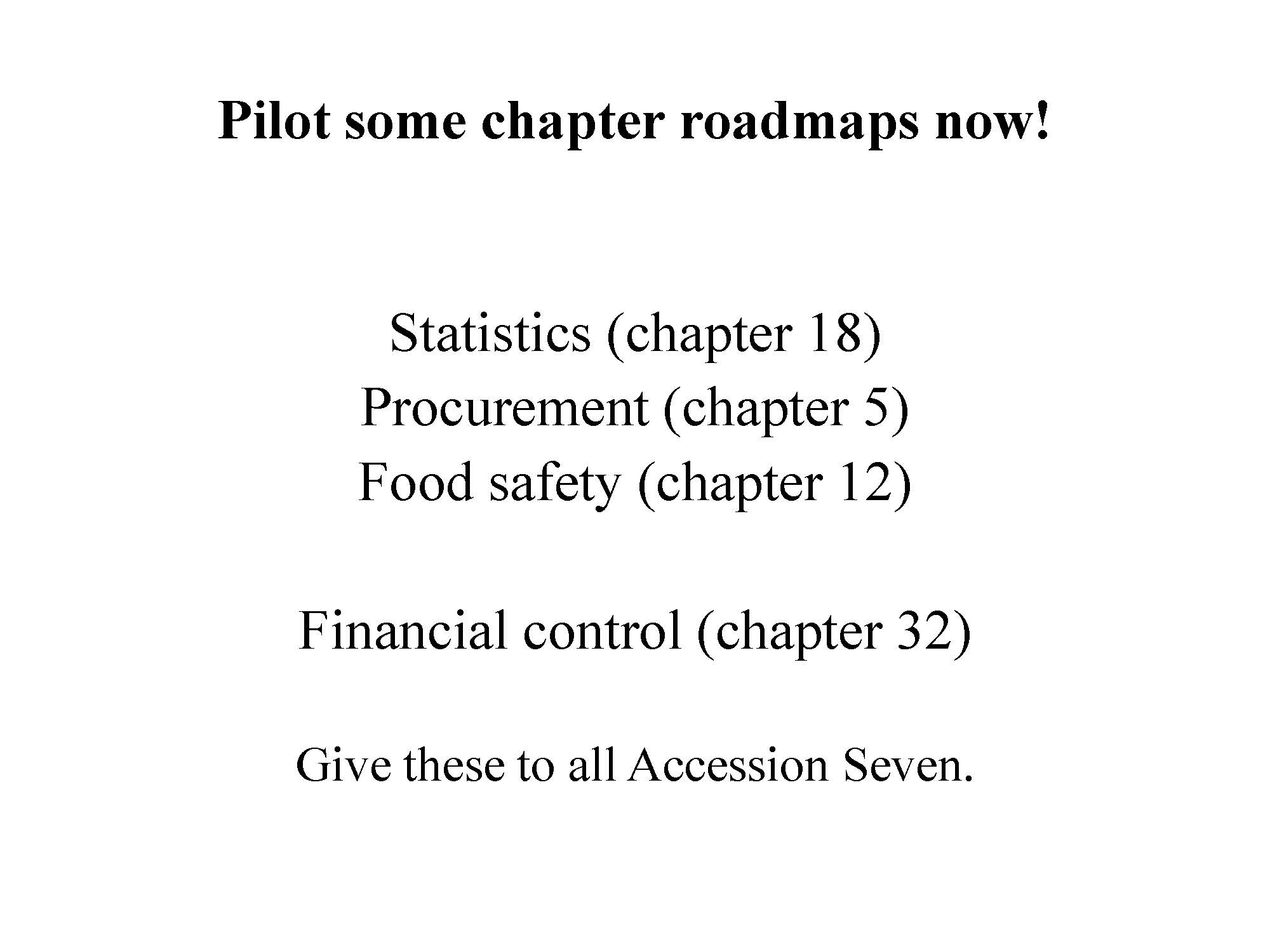

Given these experiences ESI proposes to the European Commission to put the idea of chapter roadmaps to the test as soon as possible.

We propose that DG enlargement develops four pilot roadmaps, and then assess progress in these four fields similar to the way the Commission has done with visa roadmaps; for all accession countries, already in the 2015 Progress Reports: Statistics (fundamental for economic governance), Procurement (central to progress in the rule of law and the fight against corruption), food safety (key to attract FDI in a vital sector) and Financial Control.

Giving such chapter roadmaps to all seven countries, and assessing them by reference to these benchmarks in 2015, would mark a small but very important improvement in the current process of writing progress reports.

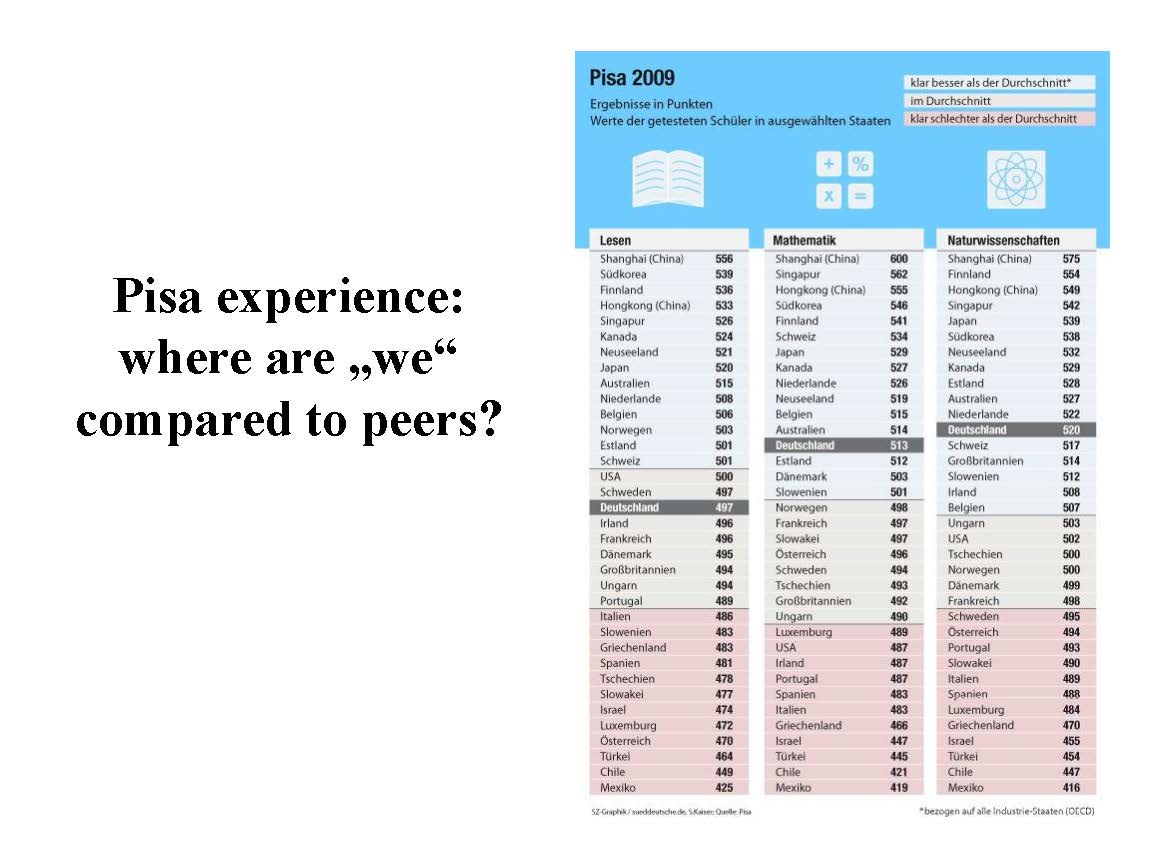

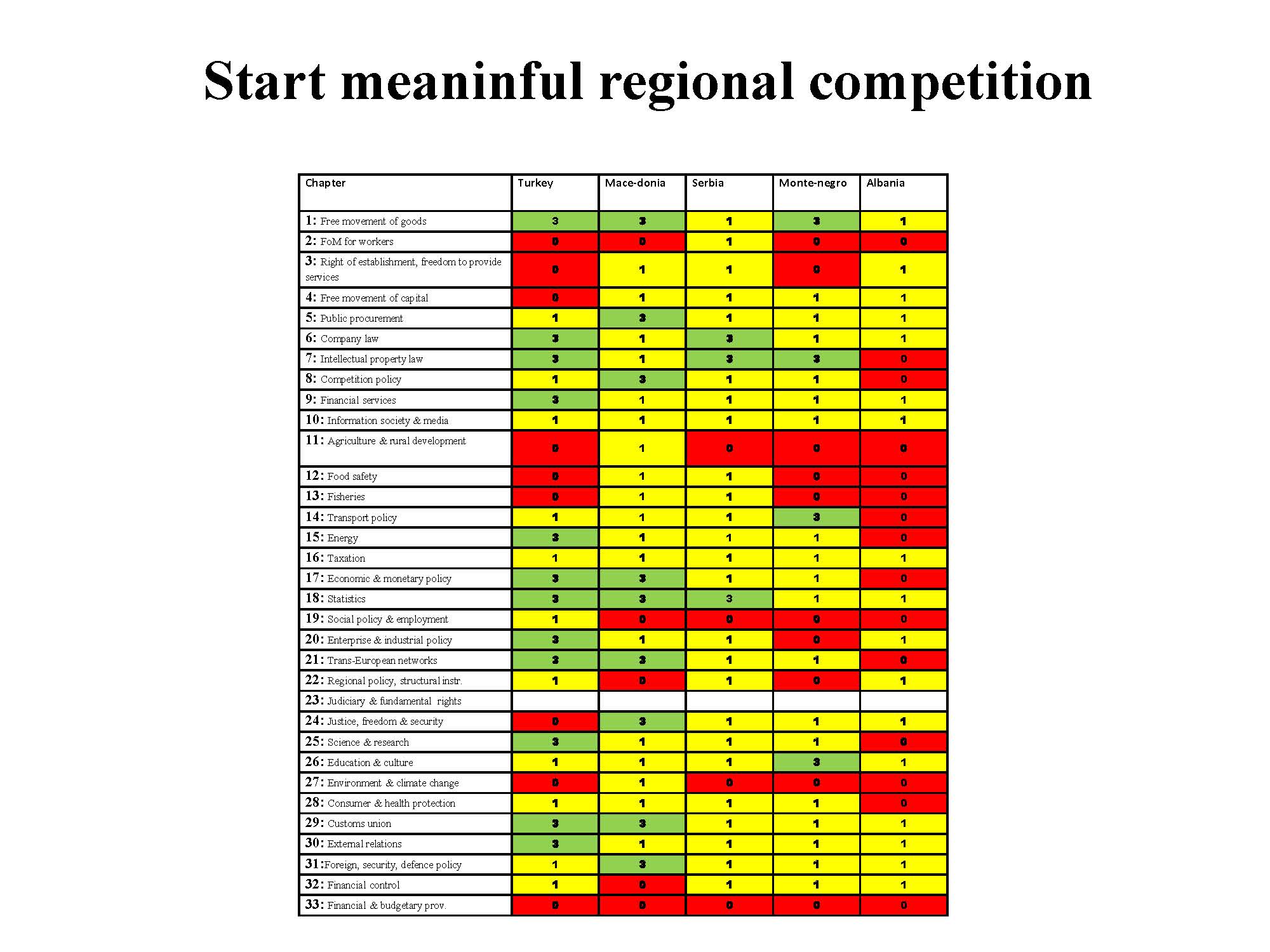

One additional effect would be similar to the regional competition we have seen in the field of visa liberalisation. Or to the debates on public policy triggered by the Paris-based OECD with its regular publication of results of its PISA tests in the field of education.

ESI has recently presented these ideas in many capitals. Here are five of the most frequently asked questions concerning this CHAPTER ROADMAP PROPOSAL

The first question often posed concerns incentives. In the case of visa roadmaps, we hear, there was a clear “reward” at the end of the road: visa liberalisation. This was popular with the broader public. Would elites and civil servants in accession countries be equally motivated to carry out reforms in fields such as Statistics or Procurement, without a similar tangible reward?

We believe that this question puts the issue of incentives upside down.

When elected governments say that they want their countries to join the EU as a matter of national interest – and embark on a many-years-long process that requires work, focus, human resources, and that remains uncertain until the very end – they state that they have an intrinsic motivation to carry out reforms. The notion that the EU should “bribe” governments to incentivise them to carry out reforms on this path is wrong. Governments that need to be bribed in such a blunt manner should never apply, and simply risk being exposed as uninterested in the EU accession process. Then it depends on publics and voters who they will react.

The EU acccession process is more similar to a young football player being offered a place at La Masia, the famous football school of FC Barcelona; or to a budding entrepreneur admitted to Harvard Business School.

People do not get paid to submit themselves to rigorous training at these institutions of excellence. Instead they have to work hard. If they do not have intrinsic motivation this will become apparent very quickly, but in a fair manner.

However, no one would think that a young footballer might just as well practice all by himself in the street, rather than benefit from the training system of La Masia; or that a great business school has nothing to offer to those who come prepared to work hard. What such centers offer is excellent coaching by experts, precise feedback, a system of instruction that will make those who take part better at what they say they want to do in the future.

Of course there are also more specific rewards: prestige and certificates to validate progress. In the case of chapter roadmaps more FDI – if investors believe that institutions and rules are becoming more predictable. One can even imagine more donor aid for those who perform best. But the real reward is for leaders – and civil servants, who do most of the extra work and are not paid more for it – to feel that what they do is taking their countries forward; that is makes sense for their country and for them professionally. For this incentives must be intrinsic.

Can such chapter roadmaps be done for every chapter? No. We believe that they cannot be done for some chapters where there is no clear acquis (Chapter 23 or Chapter 30).

But this does not mean it cannot or should not be done for most chapters.

Does such a roadmap-approach encourage superficial reforms? Not if the roadmap – like visa roadmaps – is done well, and measures not just laws but institutions and performance. Then it becomes a very good tool also to assess progress over time and track records.

Is this a dramatic change in enlargement policy?

No. Member state do not lose their veto. They still have to agree – unanimously – to give candidate status, to open accession talks, to open chapters, to close chapters. However in the meantime the Commission helps these students get better … and provides member states with more information and feedback to assess how accession countries do.

Such an approach allows the European Commission to do better what it is already doing and already has a mandate for: assess annual progress according to the Copenhagen criteria in all countries in a strict and fair manner, provide feedback, and encourage reform.

Such a change puts the substance of actual reform back at the heart of the accession process. This is win-win situation for everyone.

Not everything will be in such roadmaps. Some reforms only make sense just before accession. The aquis changes, so it also makes sense to adapt roadmaps every two years. It is always possible for member states to insist on additional reforms as preconditions for them allowing a chapter to be closed (or even opened, though this can both happen at the same time later; Croatia actually opened and closed a number of chapters all in the final year of its talks).

These chapter roadmaps would likely capture 95 percent of reforms needed in key areas. This would be a flexible tool (fishery benchmarks might be of different importance in landlocked Macedonia than in Turkey), but in the end the idea is that the acquis is the same for all future members, as they are all heading for the same horizon.

The past five years have seen a steady erosion of trust in enlargement across the EU and in many accession countries.

Turkey has been negotiating since 2005 and has not yet opened even half its chapters.

Macedonia is a candidate since 2005 and has not yet been given a date even to open talks.

Albania became a candidate this year, but has been warned already that it could be years away from opening accession talks.

Bosnia and Herzegovina concluded its negotiations on the Stabilisation and Association Agreement in 2008 without seeing the agreement enter into force.

To an increasing number of people in accession countries the current process appears to be a stairway to nowhere. And yet, reforms in all these countries are in the interests of their citizens. They are also in the interests of the EU. As the new Commission reassesses how it can best promote reforms, we believe it should seriously look at what has worked in recent years.

We believe that improving the work that goes into the progress reports does not constitute a change in enlargement policy, and that therefore the European Commission can act on its own to improve what it is already doing. However, such a change does alter the way the Commission works. It is a real challenge, and it makes sense to implement it gradually, testing it along the way. It remains to be seen whether the new European Commission is able to carry out such reforms.

For the sake of all Europeans, we can only hope it is.

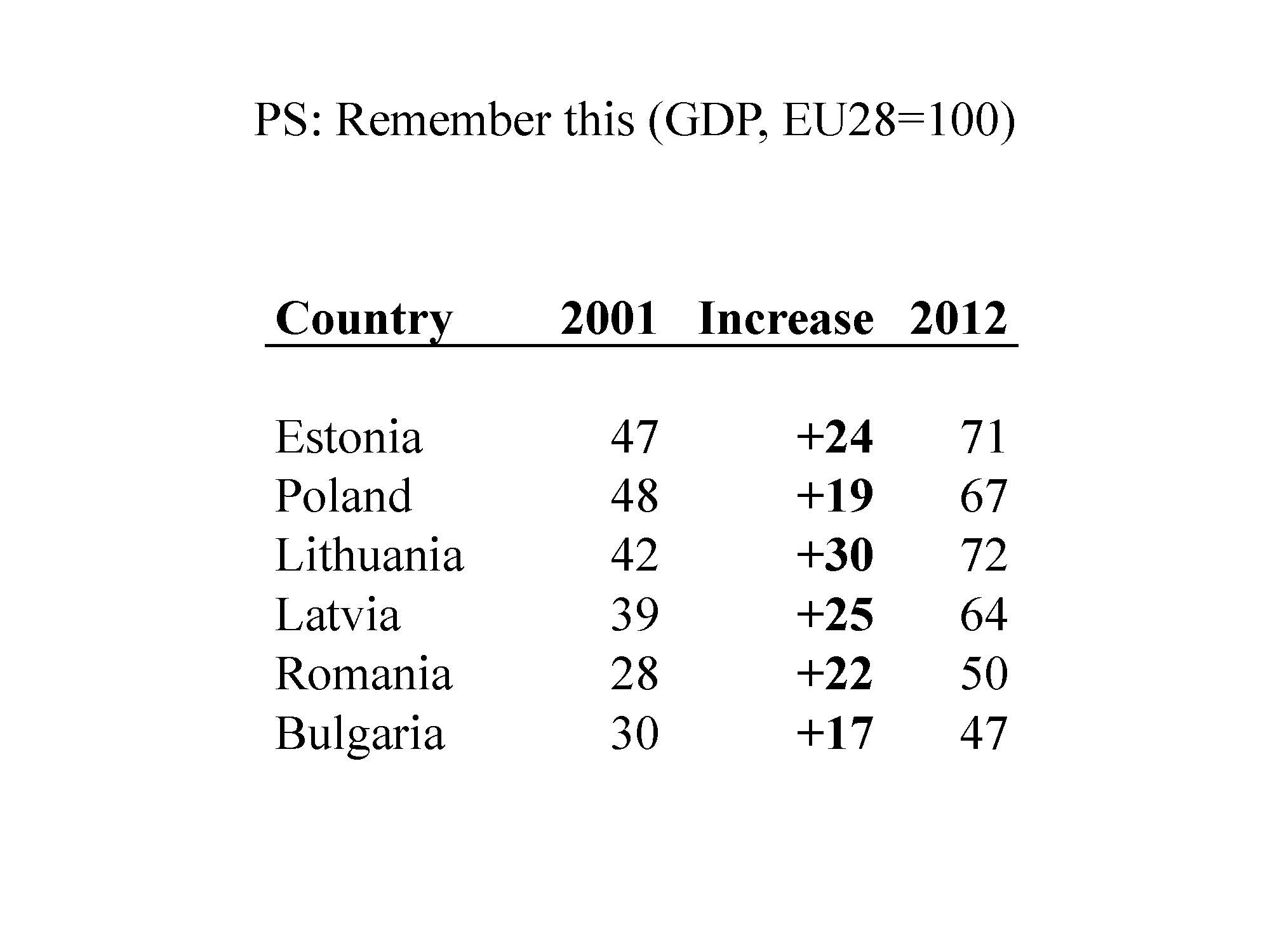

Earlier presentation:

See also:

This is a standard claim, made by EU member states and by the European Commission. On 7 June 2014 the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, made a video podcast on Western Balkan enlargement in which she asserted: “There are very clear criteria for the steps needed to move closer to the EU. In the end it is up to each country whether they pass through this process rapidly or not.” The message: “the process is fair. It depends on merit. It depends on you.”

This is a standard claim, made by EU member states and by the European Commission. On 7 June 2014 the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, made a video podcast on Western Balkan enlargement in which she asserted: “There are very clear criteria for the steps needed to move closer to the EU. In the end it is up to each country whether they pass through this process rapidly or not.” The message: “the process is fair. It depends on merit. It depends on you.”