Ein Artikel in der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung vom 27 September 2016 (Brüssel: Vertrag mit Türkei bewährt sich, FAZ, Seite 2, Dienstag) zeigt zweierlei: die Europäische Kommission erkennt nicht, was notwendig ist, um das EU-Türkei Abkommen umzusetzen. Sie versäumt es, Politiker und die Öffentlichkeit aufzurütteln. Stattdessen verschleiert sie Probleme. Das ist unverantwortlich und gefährlich. Wenn nichts passiert, könnte das Abkommen in den nächsten Wochen in sich zusammenbrechen. In diesem kurzen Überblick stehen die Aussagen der Kommission, die in dem Artikel zitiert werden, den tatsächlichen Entwicklungen gegenüber. Ein aufmerksamer Leser kann von selbst erkennen, dass hier vieles nicht zusammenpasst:

Die Zahl der Flüchtlinge, die in der Ägäis ankommen

Der Artikel beginnt optimistisch:

„Das vor sechs Monaten zwischen der EU und der Türkei vereinbarte Flüchtlingsabkommen scheint sich insgesamt zu bewähren. Zu dieser positiven Einschätzung ist die Europäische Kommission in einer Bilanz gelangt. ‚Ich habe keine großen Befürchtungen, dass das Abkommen zwischen der EU und der Türkei scheitert. Es steht für beide Seiten zu viel auf dem Spiel’, sagte ein mit dem Dossier betrauter Beamter am Montag.“

Dafür bietet der ungenannte Beamte folgende Argumente:

„Die Zahl der über die Ägäis aus der Türkei auf die griechischen Inseln gelangenden Flüchtlinge sei mit zuletzt durchschnittlich hundert am Tag auf einem ‚historisch niedrigen Stand’.“

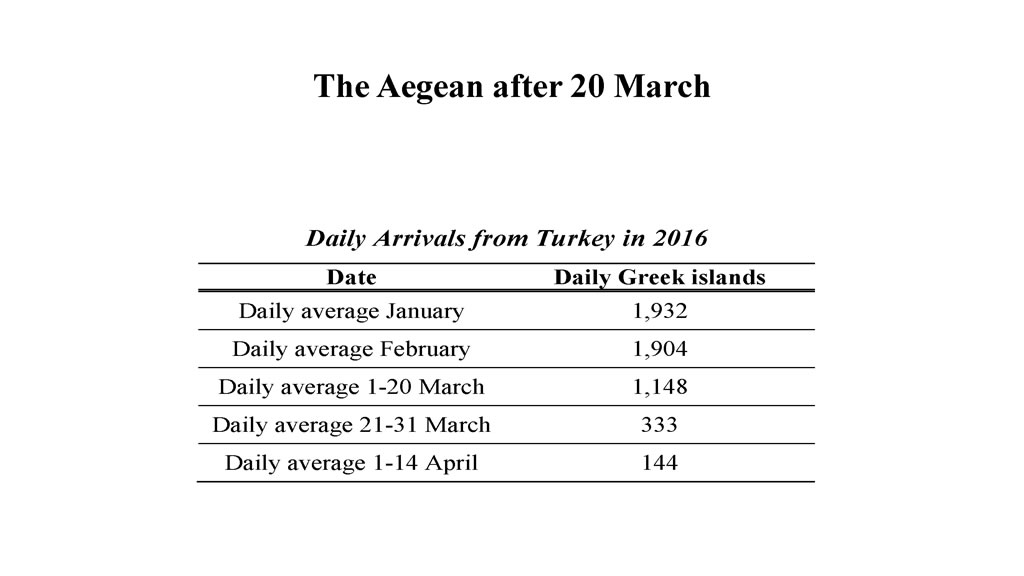

Ankunft von Flüchtlingen aus der Türkei auf griechischen Inseln (2016)[1]

| Datum | Ankommende Flüchtlinge |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt Januar | 1,932 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt Februar | 1,904 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt 1-20 März | 1,148 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt 21-31 März | 333 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt April | 121 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt Mai | 55 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt Juni | 51 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt Juli | 59 |

| Täglicher Durchschnitt August | 111 |

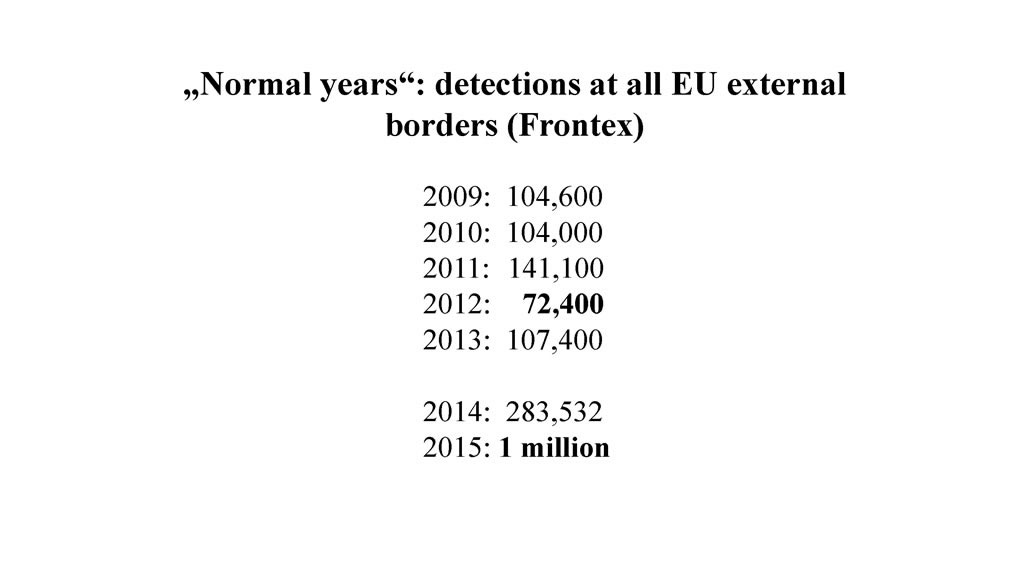

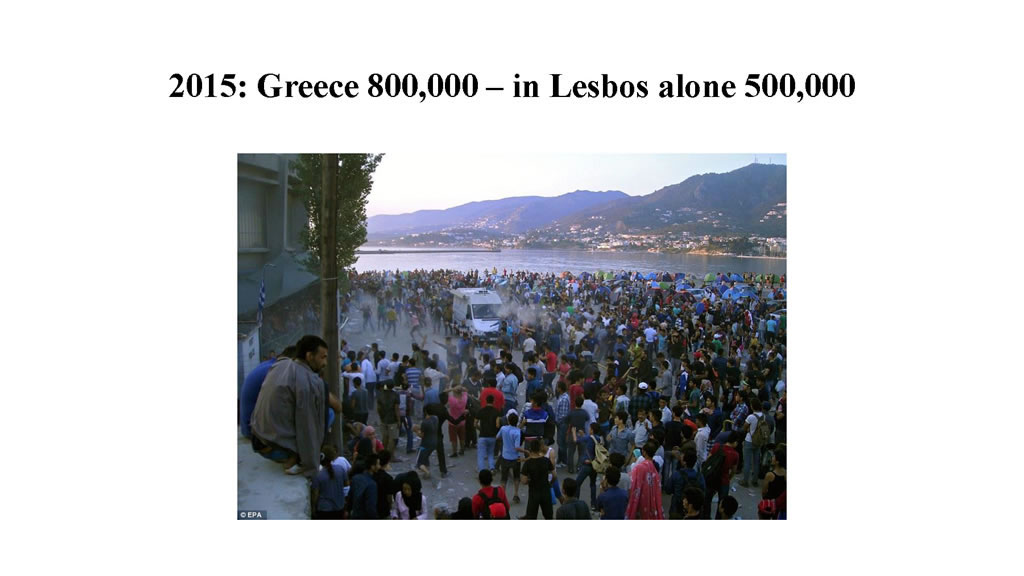

Die Zahl der ankommenden Flüchtlinge lag im August bei durchschnittlich 111 am Tag. Das sind doppelt so viel wie im Mai oder Juni. Dieser Trend ist besorgniserregend. Es ist auch kein „historisch niedriger Stand“: auf ein Jahr umgelegt bedeuten 111 Ankommende am Tag insgesamt etwa 40,000 Ankommende im Jahr.

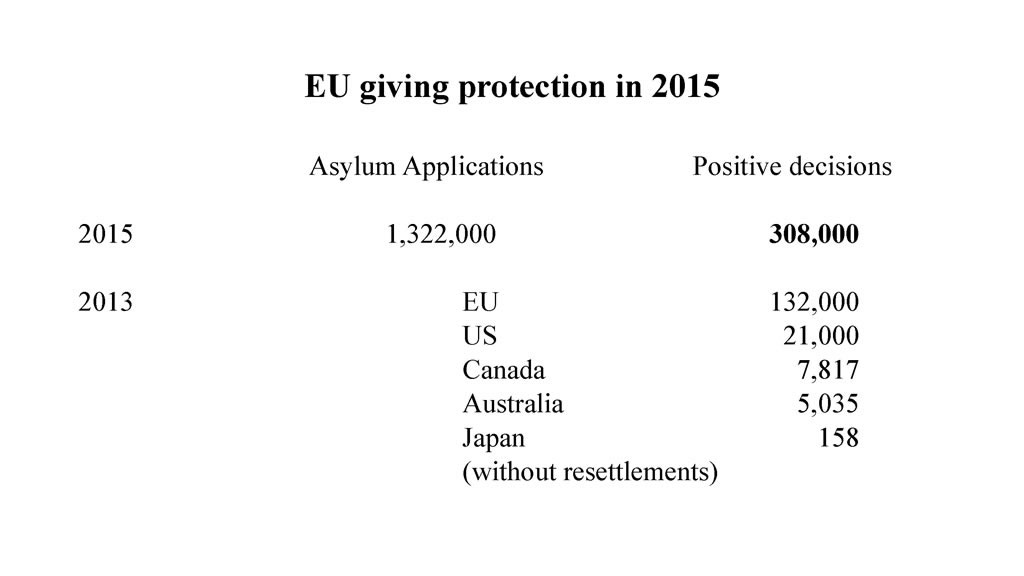

Um das einzuordnen hilft es, sich die Gesamtzahl ALLER, die die EU Außengrenzen in den letzten Jahren überquert haben, vor Augen zu halten: das waren von 2009 bis 2013 jährlich durchschnittlich 110,000 an ALLEN EU Außengrenzen. 40,000 im Jahr nur in der Ägäis wären eine historisch hohe Zahl, die nur verglichen mit dem Ausnahmejahr 2015 (als über 800,000 ankamen) „niedrig“ erscheinen mag. Dass der negative Trend der letzten Wochen nicht einmal erwähnt wird ist auch merkwürdig.

Die Zahl jener, die von den Inseln in die Türkei zurückgeschickt werden

„Positiv wird in der Kommission herausgestellt, dass seit Inkrafttreten des Abkommens von den griechischen Inseln bis zum Montag insgesamt 578 Flüchtlinge in die Türkei zurückgeschickt worden seien. Allein am Montag brachte ein Schiff 70 Migranten von der Insel Lesbos in die Türkei Dikili zurück.“

Das bedeutet, dass seit Inkrafttreten des Abkommens im Durchschnitt pro Monat weniger als 100 Flüchtlinge in die Türkei zurückgeschickt wurden – weniger als derzeit täglich auf den Inseln ankommen.

Was die Kommission nicht erklärt, ist erneut der tatsächliche Trend. Der sieht nämlich so aus: auch im September wurden insgesamt nur 90 Leute zurückgebracht. Im August waren es 16, im Juli niemand, im Juni 21 und im Mai 55. Die allermeisten wurden zu Beginn des Abkommens, im April (386), zurückgebracht. In der ersten Oktoberwoche ist noch einmal ein Transfer von 75 Menschen geplant. Doch danach ist es wieder unklar aus wie es weitergeht. Von einer Trendwende kann derzeit keine Rede sein.

Transfer von Migranten aus Griechenland in die Türkei bis 27 September 2016[2]

| Date | Transfers |

| 4 April | 202 |

| 8 April | 123 |

| 26 April | 49 |

| 27 April | 12 |

| 18 May | 4 |

| 20 May | 51 |

| 8 June | 8 |

| 9 June | 13 |

| 16 June | 6 |

| 17 August | 8 |

| 18 August | 6 |

| 25 August | 2 |

| 7 September | 5 |

| 8 September | 13 |

| 23 September | 7 |

| 26 September | 70 |

| Total | 579 |

Die Kommission erklärt übrigens selbst, warum es auch in den nächsten Monaten nur sehr wenige Rückführungen geben wird:

„Derzeit gibt es mit jeweils drei Mitgliedern besetzte Berufungsgremien, die derzeit monatlich nur 200 Fälle zum Abschluss bringen können Zur Bewältigung dieses ‚Flaschenhalses’ müssten die Verfahren gestrafft, mehr Personal müsse eingestellt werden. Ziel sei es, die Dauer des Prüfverfahrens auf zwei bis drei Wochen zu begrenzen.”

Das bedeutet: egal wie viele Fälle die Asylbehörde in erster Instanz derzeit bearbeitet (und es sind nicht viele – siehe weiter unten), die erwartete Zahl derjenigen, die von der zweiten Instanz monatlich „zum Abschluss“ gebracht wird, liegt bei „nur 200“ … und das bedeutet noch nicht, dass alle 200 auch in die Türkei zurückgebracht werden.

Derzeit gibt es noch keine Erfahrung mit den Berufungsgremien, aber selbst wenn ALLE 200 Fälle pro Monat in einem Rückführungsentscheid in die Türkei enden, wären das weniger als derzeit in ZWEI TAGEN auf die Inseln kommen.

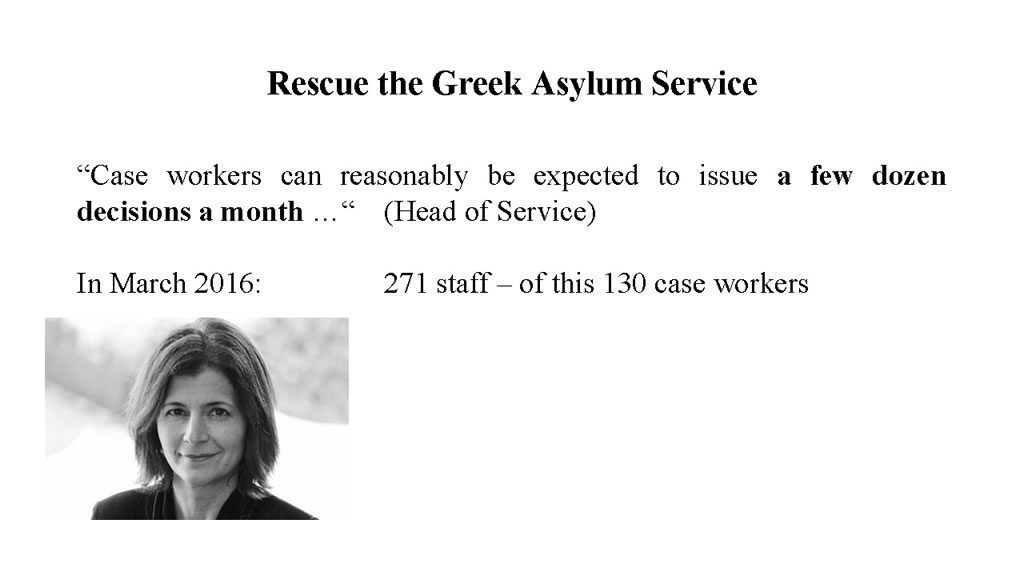

Die kleine griechische Asylbehörde ist der Aufgabe auf den Inseln nicht gewachsen.

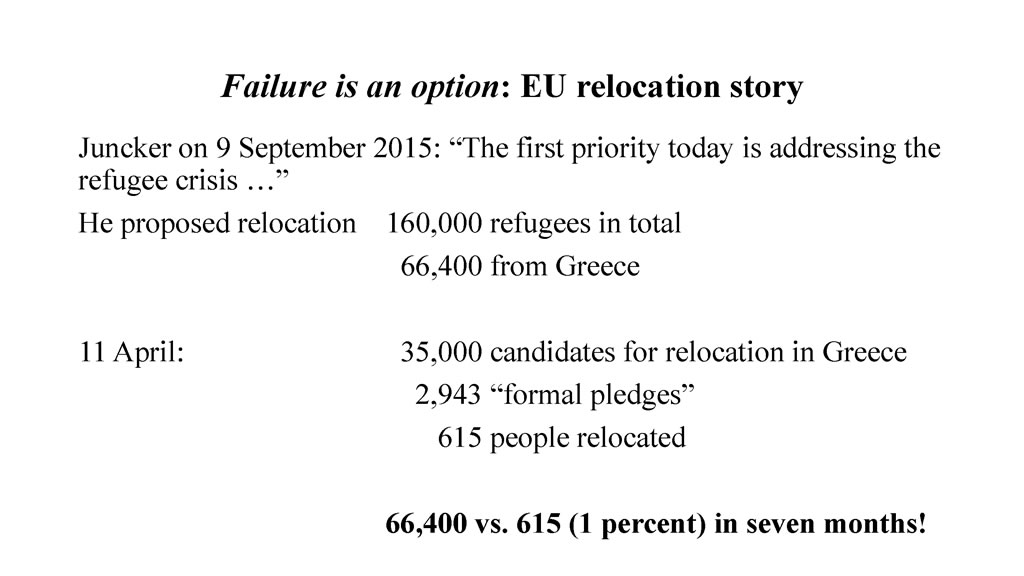

„In der EU-Behörde wird zudem erwartet, dass auch die Zahl der ‚Rückführungen’ von Flüchtlingen aus Griechenland in die Türkei in Kürze deutlich zunehmen wird. Inzwischen sei in Griechenland über die Zulässigkeit von rund 3500 Asylanträgen – davon gut 3000 von syrischen Flüchtlingen – entschieden worden. Dies entspricht der im März gegebenen Zusage, Asylanträge im Schnellverfahren zu prüfen.“

Doch selbst wenn 3,500 Anträge in sechs Monaten entschieden wurden, dann sind das weniger als 600 im Monat. Derzeit kommen PRO WOCHE mehr Flüchtlinge und Migranten auf den Inseln an.

Man kann es drehen wie man will: sechs Monate nach Inkrafttreten des Abkommens haben weder die erste Instanz der Asylbehörde, noch die Berufungskommissionen, noch die – immer noch dramatisch unterbesetzte – EASO Mission auch nur ansatzweise die Ressourcen, die notwendig wären zu verhindern, dass die Schere zwischen der Zahl der Ankommenden und der Zahl der in die Türkei zurückgeführten nicht weiter aufgeht.

Die letzte der zitierten Aussagen der Kommission wirkt vor diesem Hintergrund bemerkenswert:

„Günstig habe sich zuletzt die Versorgungslage für die Flüchtlinge entwickelt.“

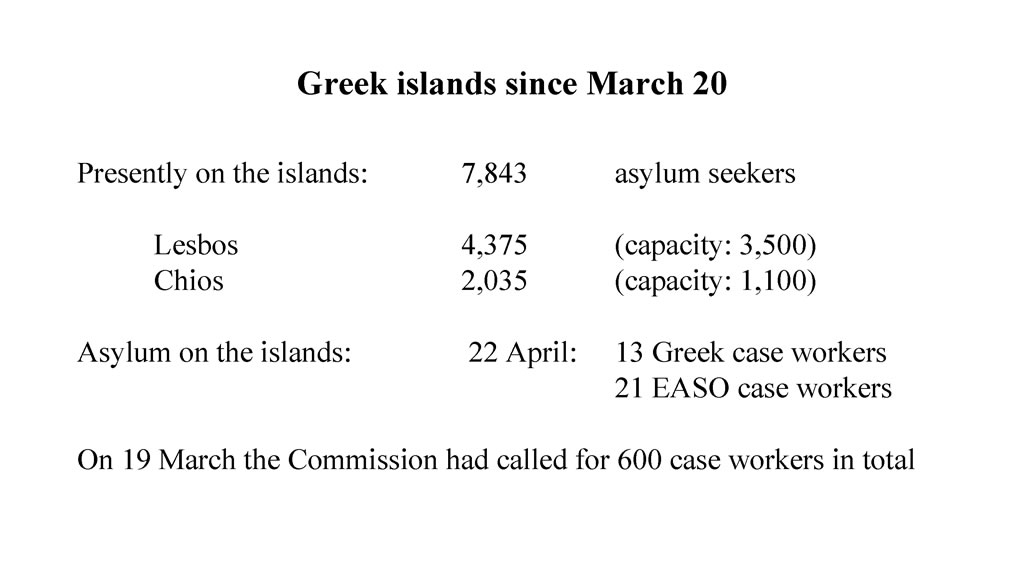

Dass sich die „Versorgungslage“ auf den Inseln günstig entwickelt haben soll, nachdem das wichtigste Lager Moria auf Lesbos erst vor kurzem brannte, während die Differenz zwischen Bedarf und Resourcen immer grösser wird, und obwohl Proteste der Bevölkerung auf den Inseln immer mehr zunehmen, ist schwer zu glauben. Es widerspricht auch dem, was Journalisten und Menschenrechtsorganisationen von den Inseln berichten. Abgesehen davon ist jedem Laien klar was es bedeutet, wenn

- sich heute doppelt so viele Menschen auf den Inseln befinden als Kapazitäten vorhanden sind, sie gut zu versorgen (UNHCR);

- jeden Tag so viele Menschen auf den Inseln ankommen wie durchschnittlich im Monat in die Türkei gebracht werden;

- der Trend zeigt, dass die Zahl der Ankommenden steigt, die Effizienz der Behörden aber seit Monaten stagniert.

All das wirft die Frage auf: Wie kann eine Organisation, die bestehende Probleme und alarmierende Trends nicht wahrnimmt, diese Probleme lösen? Und was macht die Europäische Kommission, wenn in wenigen Wochen die griechischen Behörden das Handtuch werfen müssen und tausende von den Inseln wegbringen, und damit den Schlepper in der Türkei signalisieren, dass das ganze Abkommen einzustürzen beginnt?

Kapazität und Auslastung in den Lagern auf den griechischen Inseln, 13. September 2016[3]

| Island | Kapazität | Auslastung |

| Lesvos | 3,500 | 5,660 |

| Chios | 1,100 | 3,598 |

| Kos | 1,000 | 1,540 |

| Samos | 850 | 1,425 |

| Leros | 1,000 | 702 |

| Rhodes | 136 | |

| Karpathos | 71 | |

| Kalymnos | 24 | |

| Megisti | 14 | |

| Total | 7,450 | 13,171 |

PS: Was tatsächlich – schnell – passieren müsste hat ESI erst vor kurzem in diesem Papier beschrieben: Background paper: On solid ground? Eleven facts about the EU-Turkey Agreement (12 September 2016)

Wir haben unsere Vorschläge auch in vielen Gesprächen, in internationalen Medien oder bei Veranstaltungen in Den Haag, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Wien und Berlin erkläutert:

- ORF, “Im Zentrum” – Gerald Knaus in TV debate on the refugee crisis – (“In focus”) (25 September 2016)

- Vienna – Meetings and presentations on the implementation of the EU-Turkey Agreement (22 September 2016)

- Athens – ESI presentation at ELIAMEP: The EU, asylum, and borders after Brexit (21 September 2016)

- Netherlands – ESI meetings and presentations on the current state of the implementation of the EU-Turkey Agreement (7 September 2016)

- Nieuwsuur, “Bedenker Turkijedeal vindt uitwerking een schande” – interview with Gerald Knaus – (“The architect of the Turkey deal considers its effects a disgrace”) (1 September 2016)

- Kathimerini, Eurydice Bersi, “Κνάους: «Eλλειψη σοβαρότητας στο προσφυγικό»” (“There is a lack of seriousness in how we deal with the refugee issue”) (22 September 2016)

- ORF, ZIB24, “Migrationsfachmann Knaus: ‘Alle EU-Pläne gescheitert'” (“Migration expert Knaus: ‘All EU plans have failed'”) (22 September 2016)

- De Redactie (Belgian TV), “50.000 vluchtelingen in Griekenland zijn ten einde raad” – interview with Gerald Knaus – (“50,000 refugees in Greece are desperate”) (22 September 2016)

[1] Source: UNHCR (Weekly report, 4 August 2016)

[2] Source: European Commission

On Dutch news show

On Dutch news show