How long does it take for the whole proud city of New York to be swallowed by nature?

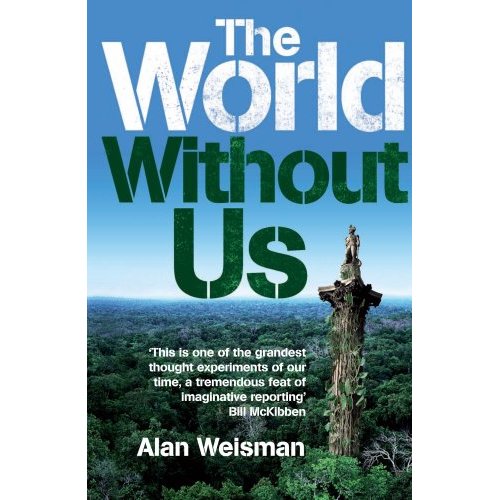

In his magical “The World without us” (a good christmas present for friends, by the way) Alan Weisman makes a thought experiment: he imagines a world without human beings and asks what would happen, among other things, to the urban landscape of Manhattan. His conclusion is that “the time it would take nature to rid itself of what urbanity has wrought may be less than we might suspect.”

Without the pumps being maintained, which every day keep 13 million gallons (49 million liters) of water from overflowing the subway tunnels these tunnels would quickly fill up: within half an hour water would reach a level where trains can no longer pass. Within 36 hours the tunnels would fill up completely. Within 20 years the steel columns which support the street above the train-lines would buckle. By then the city would be well on its way to revert to a forest (click here for his slideshow):

“In the first few years with no heat, pipes burst all over town, the freeze-thaw cycle moves indoors, and things start to seriously deteriorate. Buildings groan as their innards expand and contract; joints between walls and rooflines separate. Where they do, rain leaks in, bolts rust, and facing pops off, exposing insulation. If the city hasn’t burned yet, it will now … Within two decades, lightning rods have begun to rust and snap, and roof fires leap among buildings, entering panneled offices filled with paper fuel … Red-tailed hawks and peregrine falcons nest in increasingly skeletal high-rise structures.”

In the same way, Weisman notes, Europe without human beings would revert to original forest. Soon much of the old world would turn into the “misty, brooding forest that loomed behind your eyelids when, as a child, someone read the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales.” (to see Weisman in action in the Daily Show go here: “a lot of stuff would go down rather fast”).

There are a number of serious points in this tale.

First, decline is not a “problem” that human ingenuity can “solve”. All we can do is keep going: once those pumps go off, all the wisdom and craft that have gone into the New York subway system cannot prevent it to come to a halt within hours. Second, although crises and decay are not exceptional moments but the stuff of life itself what constitutes a serious crisis very much depends on the perspective of the onlooker. The collapse of Manhattan might be a serious example of decline for some, but as ornithologist Steve Hilty told Alan Weisman “If humans were gone at least a third of all birds on Earth might not even notice.”

Turning from birds to humans and from Manhattan to Brussels – and keeping in mind those two points (1. things are always in decline and 2. assessing how serious it is depends on where we stand) – the real concern I hope to share with you today is whether it is true, as a recent gathering of smart people discussed in Vienna, that today – at the end of the first decade of the third millenium – “Europe” is “in decline”?

Note that even as we pose the question, we can see what is wrong with it. Of course Europe is in decline if we look at it from the biological perspective. And as many have recently pointed out, with seriously raised eyebrows, the mere fact that there are less of us (Europeans) in the future than there are today suggests that there is something to this biological perspective. Pointing to Europe’s low birthrates, one concerned American, Robert Samuelson, writes in the Washington Post in June 2005 (title: “The end of Europe”) that

“in a century – if these rates continue – there won’t be many Germans in Germany or Italians in Italy. Even assuming some increase in birthrates and continued immigration, Western Europe’s population grows dramatically greyer, projects the US Census Bureau …”

And not only the Census Bureau. As Rainer Munz, a leading European demographer, told our group at the very outset of our seminar, demography is about slow processes which advance with a degree of inexorability: thus “we can see ahead for the next 45 to 50 years” (which for many of us is the rest of our lifespan), and what we see is this: for the period up to 2050 “without immigration, the population of western and central Europe would have declined by 57 million by 2050.” The working age population would shrink by a striking 88 million people!

This is obviously going to cause some problems: retiring at age 60, or 62 (as recently proposed by the French President, triggering major protests), is not going to be an affordable option, if we want to maintain even a rudimentary welfare state and old age pension system. To maintain their living standards Europeans will have to work longer; more people will have to work (including more women); and Europe will need to remain open to immigration from parts of the world where there is still (for now) population growth. The only countries in Europe with a growing domestic population are small Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Ireland and Turkey (where population growth will also come to an end in the foreseeable future, however).

All of this, so Robert Samuelson, ensures that Europe is “history’s has-been”: wherever they look, Europeans see their way of life threatened. At the same time they remain immobilised by their problems. European do not want more migration. They also do not want to become more competitive by adapting the American way of running their economies (i.e. reduce regulations and taxes). Therefore, “Europe as we know it is slowly going out of business.”

This sounds ominous. Of course, there are things that could be done for Europeans to remain in business, Rainer Munz tells us. The average age for people to retire in Austria today is still only 58: this could and should rise. Many more women could work (in some European countries, particularly in Scandinavia, they do). People could decide to have (some) more children. We could consume less in old age. And there could be more immigrants. But even if all of this happens, there might still be less Europeans in 2050 than now, and less people adding to Europe’s GDP.

So Europe is in decline. And this means inevitably a loss of influence also on the global stage. As Robert Samuelson concludes:

“Ever since 1498, after Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and opened trade to the Far East, Europe has shaped global history, for good and ill. It settled North and South America, invented modern science, led the Industrial Revolution, oversaw the slave trade, created huge colonial empires, and unleashed the world’s two most destructive wars. This pivotal Europe is now vanishing …”

But hold on, I wonder: what does it really mean to say that pivotal Europe has shaped history “for good and ill”? Let’s ask ourselves three naive questions:

1. Clearly “Europe” (and “European influence”) is an abstraction? Throughout the 19 century European Empires were actually bitter rivals, fearful of each other. Even if they had global Empires, as countries such as the Netherlands or Belgium had until the middle of the 20th century in Asia and Africa, these European nations were extremely vulnerable in the face of hostile neighbours (and were indeed invaded a few times by some of them in the 20th century). Also, the colonial era ended many decades ago (which was not obviously a loss to the world, or to European citizens, but that is a different debate). During the cold war, peace in Europe was in part the result of the fact that Europe’s most powerful previous trouble-maker (Germany) was divided, with Nato and Warsaw Pact troops, armed to the teeth, staring at each other across the Fulda gap. Clearly the average Central and East European had little global influence then either (or should he or she have felt pride that some citizens of the world were in awe at the combined military machine of the Warsaw Pact?).

In general, when did the average Portuguese or Spaniard, Austrian or Swede last feel that her opinion, or the leaders elected by her, had more global influence than they have today? Is the late colonial era really the yardstick by which to measure declining European influence? (at this stage of our musings we might notice how very Anglo-Saxon, or rather British, so much current thinking about European decline is: it assumes first that European colonialism was more or less a civilising and beneficial force, and second that the end of world power status was relatively recent. Few Poles or Greeks would recognise themselves in such a narrative).

2. Has the influence of the European Union also declined in recent decades? If we look at it as a concrete “European” geopolitical entity the story of the past three decades suggests otherwise. The EU has grown substantially as a result of successive enlargements, from some 300 million people to more than 500 million. Arguably, the EU today has more potential clout than the European Economic Community had at any moment during the Cold War. Or than the EU had in the 1990s, when Europeans stood by helplessly and watched the Balkans burn.

3. What is so bad about getting older? Rainer Munz presents a striking statistic: “in the course of the twenty-first century, our life expectancy is likely to rise by another 20 years. If we extrapolate the pace of recent decades – a plus of three months per year – then the gain would even be significantly greater.” This means that de facto we do not live just 24 hours, but at least 25 hours every day – although we only get to consume the extra time at the end of our lives (which I certainly regret on many busy days).

In short, we all understand the problems caused by an aging work force. But we might also pause to note that behind this “cause of decline” stands a major positive trend: the dramatic improvement in the chance for all of us (Europeans of our generation) to live to old age. We are likely to see our children and grand children – if we chose to have them -grow older as well. Yes, we might be lonely in old age but this is our choice in a way it never was for previous generations. Let’s plan to work until we are 70. And let’s assume that we will need to change profession at age 40, again at 60 and still learn new tricks when we are 75. This will be stressful. But we will not be dead.

What all of this means is that we – European societies and citizens – have choices our ancestors never had before. We can chose what to do with our longer lives. We can chose to have children and (because others have fewer) these might have to worry less about finding work. We certainly have to worry less about them going off to fight in a major war.

We can also chose to shape a credible EU that at least retains the global influence it has at the moment (and whose leaders do not indulge in fantasies inspired by a supposed Siglo de Oro of European imperialism of the kind “if only Europeans could – like Hernan Cortes in 1519 – set out and conquer a nation of seven million Indians with a few hundred adventurers”). Of course, Europeans will disagree on how such an EU should look like. Therefore changing anything will have to be incremental and slow. This will be true for reforming the Euro. This will also be true for future enlargement. It has generally been true in the history of European integration.

And, above all else, we should think hard how to best meet the challenges which we know we are going to face: further immigration, (somewhat) more diversity, and the obvious fact that a growing minority in our aging European societies are going to be Muslim. We could chose to go down the Thilo Sarrazin route: to deplore, as the former Bundesbanker did in a best-selling book (“Germany abolishes itself”) the fading of an era when most of Berlin’s population was Christian (or at least Judeo-Christian, to judge by the new rhetoric which even far-right anti-Islamic parties across Europe have cynically started to embrace) and white. Judging by this reference point it is those countries which never had or are unlikely to soon have large religious or ethnic minorities that are going to inherit the future … Only: where does this theory place aging Japan? Most of the multicultural rest of the world? Africa, Brazil, India, China, Indonesia? Multi-ethnic countries which grow and homogenous countries which do not? Or we could see the challenges or growing societal pluralism as a sideproduct of our success: as a result of peace and prosperity.

Where does this debate on the decline of Eurabia leave the US? There was, after all, also an American Sarrazin, another elderly man with grey hair, the late Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington, making a rather similar case. Not about Islam only, which he did already in 1993 (in his bestselling and terrible “Clash of Civilisations”), but about the challenges posed to America’s national identity by … Hispanization! Huntington warned a few years ago that Mexican immigration

“looms as a unique and disturbing challenge to our cultural integrity, to our national identity, and potentially to our future as a country.”

This challenge to US identity is of a quasi-military nature:

“In almost every recent year the Border Patrol has stopped about 1 million people attempting to enter the US illegally from Mexico. It is generally estimated that about 300,000 make it across illegally. If over 1 million Mexican soldiers crossed the border, America would treat it as a major threat to their national security and react accordingly. The invasion of over 1 million Mexican civilians is a comparable threat to American societal security, and Americans should react to it with comparable vigour.”

Thus, while Latinos are the problem in the US (for Huntington), Muslims are the problem in Europe (for Sarrazin and many, many others), and both for the same supposed reason: they cannot be integrated into mainstream culture! in the US it is Anglo-Protestant Culture which is under siege … in Europe it is the Abendland which is set to decline. Thus Europe is doomed just as California (which was one of the whitest states in the US) is doomed, and arguably both are in decline since the 1960s … Some years ago former CIA director William Colby warned about the future emergence of a “Spanish speaking Quebec in the US Southwest.” Stefan Luft, a German author, makes the same claims for Germany’s cities. So then both the US and Europe are doomed …

This theory – Muslim migration causes the decline of Europe – is also developed in Walter Laqueur’s “The last days of Europe“, another book which starts with demography and ends with the near certain failure of integrating Muslims. For Laqueur the best place to observer the death of old Europe is “Neukolln or Cottbusser Tor” in Berlin. He sees a dark future for a doomed continent which is all the more dangerous because it is still hidden: “on the surface, everything seems normal, even attractive. But Europe as we knew it is bound to change, probably out of recognition for a number of reasons …” A similar theory of decline is developed by Bruce Thornton in Decline and Fall – Europe’s slow motion suicide (2007) and in Christopher Caldwell’s Reflections on the Revolution in Europe (2009). And these were books written before the global economic crisis or the latest troubles of the Euro …

Islamisation is, of course, only one (if for many the most popular) explanation, besides aging, why Europe in the early 21st century is supposedly in decline. Different authors present different arguments, so let us look at a few more “causes of decline”:

- there is the theory of Huntington presented in the foreword of his book “Who are we?” that “so long as Americans see their nation endangered, they are likely to have a high sense of identity with it. If their perception of threat fades, other identities could again take precedence over national identity.” Hm. While I can see how this could be applied to today’s Europeans, less likely to go to war than at any point in history, interesting policy conclusions follow from this analysis …

- there is the identification by Walter Laqueur of another crucial reason for the “aggressiveness” of Muslim communities in Europe in particular: “Sexual repression almost certainly is another factor that is seldom if ever discussed within their communities or by outside observers. It could well be that such repression generates extra aggression …”. We learn: a Europe which is less sexually repressed is less aggressive. This seems intuitively right, except that in the aggregate Europe was probably never in its history less sexually repressed than today (certainly this seems to be true for Berlin …) and yet, its decline is still not stopped by the neo-pagan attitudes to sexuality. And where does this theory leave China or the US, clearly some way behind most Europeans on the scale of licentiousness?

- there is the claim in an article (Europe’s Determination to Decline) by Bjorn Lomberg that it is Europe’s commitment to deal with climate change which explains its looming decline: unilaterally reducing carbon emissions will cost the EU “$250 billion a year by 2020”:

“Unfortunately it seems as if Europe has decided that if it can’t lead the world in prosperity, it should try to lead the world in decline. By stubbornly pursuing an approach that has failed spectacularly in the past, Europe seems likely to consign itself to an ever dwindling economic position in the world, with fewer jobs and less prosperity”

Even being successful in attracting tourists is a sign of decline for some! This is the Venice-Disneyland theory of the last days. Walter Laqueur writes:

“Given the shrinking of its population, it is possible that Europe, or at any case considerable parts of it, will turn into a cultural theme park, a kind of Disneyland on a level with a certain sophistication for well-to-do visitors from China and India, something like Brugge, Venice, Versailles, Stratford-on-Avon, or Rothenburg ob der Tauber on a large scale … This scenario may appear somewhat fanciful at the moment, but given current trends it is a possibility that cannot be dismissed out of hand. Tourism has been of paramount importance in Switzerland for a long time; it is now of great (and growing) importance in France, Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal and some other countries.”

Surely it is a worrying sign of decline if too many other people would want to come and visit your hometown or country?

The end is near…

During our seminar on European decline Wolfgang Petritsch pointed out that in fact some countries in Europe were not doing too badly even at this particular moment in time: Scandinavia for instance. Others added Germany, Poland, Central Europe in general. Looking at this list makes it obvious that identifying simple causes of decline (high taxes? openness to immigration? Protestantism? Catholicism?) is almost as hard as identifying simple causes for success. But if our theories are not simple, how are we going to sell our books?

It is an akward fact for declinists that most Europeans live better today than either their parents or grandparents or great grandparents (not to go back even further). Let us certainly heed the call of Timothy Garton Ash in a recent article (Europe Wake up!):

“The eurozone is in mortal danger. European foreign policy is advancing at the pace of a drunken snail. Power shifts to Asia. The historical motors of European integration are either lost or spluttering. European leaders rearrange the deckchairs on the Titanic while lecturing the rest of the world on ocean navigation.”

But Tim also notes, in the same article, that “for standard of living and quality of life, most Europeans have never had it so good. They don’t realise how radically things need to change in order that things may remain the same.” This sums up the nature of the current crises perfectly. It also explains why most European voters do not look for a Churchill.

It is banal but it remains true: every generation faces crises. Greeks face a very serious crisis, for instance, and much will depend on the way its leaders (and voters) respond to it. It may indeed enter a period of decline, paying a price for many years (or decades) of overspending. And yet, while all this is true few Greeks would probably chose to go back to the social problems of the 1960s (when a different crisis ushered in a military coup and seven years of torture and authoritarianism), to those of the 1940s (a time of war and invasion followed by civil war) or those of the 1920s (when following a split of the country and a lost war over two millions displaced needed to be resettled in an impoverished nation).

Let us admit then that Europe is indeed in crisis and undergoing decline. But so is – depending on what criteria one choses – much of the rest of the world, if not now, then soon enough. In any open society a sense of crisis, and the threat of decline, is as enduring as the sense of hope and the awareness that good policies might improve things. And certainly both complacency and misleading crisis talk (such as identifying Hispanics or Muslims as the core problem threatening national identities) could lead to bad policies.

In the end one of our Greek seminar participants summed up the problem of European “crisis talk” best: perhaps a near permanent fear of decline is what any society needs in order to remain on its toes and adapt? Rather like those men and women looking after the pumps in the New York subway, aware that water is always there, ready to submerge their construction, we also must never feel secure. Like them, however, a state of near panic at all times is also certain to lead us to make many more bad decisions.

In an interview Alan Weisman, the author of “The World Without us” is asked whether, after writing his book, he is still “hopeful for the future”? He answers:

“I was very worried about the fate of the world, but I’m no longer worried about it. I think the world is going to be fine. Now whether the world as we know it is going to survive – that’s an open question.”

Indeed. And it always will be, says the pessimist in me. Or was this the optimist?

“Will Europe end like Venice?” Wolfgang Petritsch and Rainer Münz. Photo: ERSTE Stiftung

“What is the future of EU-Turkey relations?” Discussion with Alexandros Yannis, Kai Strittmatter, and Gerald Knaus. Photo: ERSTE Stiftung

“Is Europe a continent in decline” – Alex Rondos, Andreas Treichl, Boris Marte, Peter Hagen, Wolfgang Petritsch and Rainer Münz. Photo: ERSTE Stiftung

“From Brussels to Belgrade” – different perspectives on EU policy from Emine Bozkurt, Samuel Zbogar, Kristof Bender, Milica Delevic. Photo: ERSTE Stiftung

“Will Europe run the 21st century?” Mark Leonard discusses with Vessela Tscherneva, Ivan Krastev with Aleksandros Yannis. Photo: ERSTE Stiftung

Vienna Seminar 2010 – session with Nicu Popescu, Gerald Knaus, and Heather Grabbe on the EU and the European neighbourhood. Photo: ERSTE Stiftung