Today Monday, 2nd of June, at 4 pm in Berlin ESI, together with the German Federal Commissioner for Human Rights, organises a public debate on the future of political prisoners in Europe. Our goal is to raise the awareness about this issue and about the current failure of international organisations. It is also to discuss concrete proposals on what to do next.

It certainly seems the right moment to focus on this issue. A few days ago I got a message from Leyla Yunus, one of Azerbaijan’s most respected human rights defenders:

“No support from CoE!All of us hostages. procurator do not return our passports, which they took illegally!

Leyla”

Leyla Yunus

Leyla Yunus

We are hearing a lot from people already in prison in Azerbaijan about the economic hardships faced by their families as a result of their captivity. They also often rely on lawyers they cannot afford to pay and who therefore work pro bono, with a significant risk of later being harassed for this very work.

For all these reasons ESI and the Norwegian Helsinki Committee have put together a set of concrete proposals for discussion in Berlin. We will share it at the conference, discuss it more on Tuesday with leading practitioners, and then put it online after receiving more ideas. Here are some of these concrete ideas – an excerpt from our paper – for your feedback:

Introduction

In 2014 there are, once again, a growing number of people in Europe who are jailed for no other reason than for disagreeing with their government.

In Azerbaijan, we witness at this very moment a wave of repression against independent journalists, youth protesters, election observers, opposition leaders and Muslim believers, with many receiving long jail terms. In Russia, people who participated in peaceful protests in Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square after Vladimir Putin’s re-election in 2012 have received tough sentences. Many other activists and government critics have also been brought before the courts. Ukraine, until recently, held political prisoners. There are many political prisoners in Belarus.

Europe has the densest network of human rights NGOs in the world. All European states, with the exception of Belarus, are also members of the Council of Europe. They have thus signed and ratified the European Convention on Human Rights. They have committed themselves to respecting fundamental rights and freedoms. Belarus has accepted the human rights obligations of OSCE membership. But the problem persists, and is in fact getting much worse.

Proposal I: a European website on political prisoners

We propose to create a website on political prisoners in Europe, supported by a coalition of human rights NGOs. This could help focus and mobilise public attention.

The website would highlight all cases of people arrested for their views or on other politically motivated grounds in European countries.

In particular, it would include and consider as political prisoners for this project the following individuals, and make clear these sources:

– all prisoners of conscience recognized by Amnesty International,

– all presumed political prisoners identified by PACE rapporteurs,

– all other relevant cases identified by reputable human rights organisations, including Human Rights Watch, Reporters without Borders, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Article 19, as well as leading national human rights organisations, which have a methodology and resources and a definition to establish their lists.

Such a website would feature prisoners’ photos, biographies and information on developments in their cases. The aim would help raise awareness of political prisoners among the European public.

There might also be a separate section on alleged political prisoners. NGOs and human rights activists can submit information to the website administrator on who in their view should be included in this category and whose case would deserve to be looked at more closely. These would add pressure on the Council of Europe to find ways examine these prisoners’ cases and establish whether there are systemic patterns of politically motivated persecutions.

Proposal II: Effective support mechanisms for families

and lawyers of political prisoners

How can one most effectively mobilize support for families of political prisoners and their lawyers? What existing aid channels are there, and which organizations have already been involved? Where do gaps exists? Are there opportunities for better cooperation in raising the awareness of the need for support among different NGOs?

There appears to be a need for new support mechanisms, for ordinary people to contribute to them and for better ways to advertise them.

Proposal III: Establish a standing Expert Commission on Political Prisoners

The Council of Europe needs a new professional and credible mechanism to address the issue of political prisoners. The mechanism must be potentially applicable to any member state where a systemic pattern of repression is suspected. Its work must be compatible with the work of other institutions (the Court and rapporteurs) and complement their work. A new Expert Commission on Political Prisoners could meet both requirements.

The initiative for creating such a panel can come from the Secretary General or the Committee of Ministers. The panel then would be set up by the Committee of Ministers, which is authorized to set up “advisory and technical committees or commissions.”This would require a two-thirds majority of votes cast with a minimum of 24 votes in favour. No member state would have a veto. This panel would become active if one of the following Council of Europe institutions finds a systemic pattern of politically motivated repression!

The proposed panel on political prisoners could be composed of 3 to 7 experts. These should be former judges, presidents of national courts or senior human rights lawyers. . They would act in their individual capacity. The panel would receive necessary resources and a budget for travel, translation, legal aid, and other expenses.

Several institutions would have the right to independently appeal to this Expert Commission to begin work and examine the situation and cases in any country where they are suspecting systemic repression.

– PACE rapporteurs of any committee; the president of PACE; or the PACE bureau.

A new PACE rapporteur on political prisoners could also ask the Commission to examine – with more resources than a rapporteur will ever have – whether there is a pattern of systemic repression, which would make his or her political work easier.

– The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights.

– The Secretary General.

– A number (to be determined) of member states of the Committee of Ministers

The commission’s work would consist of investigating individual cases in a quasi-judicial capacity, but not leading to legally binding judgements, to see if there is a systematic pattern of abuse. Suggestions for cases to examine would be submitted both by the Council of Europe’s own institutions and by local and international NGOs or human rights defenders.

The panel would select a limited number of pilot cases and examine them first. Then, it would complete draft opinions on whether these individuals are political prisoners according to the PACE 2012 definition and ask the authorities of the country for feedback. After this, it would finalize its opinions and set a reasonable deadline for the authorities to react by granting a release or retrial and carrying out reforms to stop systemic abuse of this kind.

After the deadline, either the Secretary General or a PACE rapporteur for political prisoners or the Commissioner for Human Rights should assess whether the authorities have acted on the findings of the experts.

If this is not the case, the Assembly and the Committee of Ministers should consider sanctions, including a boycott of official Council of Europe meetings in this country and loss of voting rights. Also, no such country would be able to assume the chairmanship of the Council of Europe as long as the situation is not resolved.

A similar panel of legal experts was already successfully used by the Council of Europe in 2001-2004 for Azerbaijan. The combined efforts of the experts and PACE rapporteurs led to the determination that there were 62 presumed political prisoners in Azerbaijan and to the release of hundreds of alleged political prisoners in the country.

Currently in the case of Azerbaijan, PACE did already adopt a resolution on 23 January 2013 stating that there were not only individual cases but in fact a systemic pattern of arrests. The Council’s Commissioner for Human Rights has also identified “selective criminal prosecution” of dissenters in Azerbaijan. Either of these findings would in the future automatically trigger the Commission to look into the situation more closely.

Proposal IV: The future of the Russian delegation in PACE

In April 2014, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and military involvement in the Ukraine crisis, PACE voted to suspend the voting rights of the Russian delegation until the end of the year. It should be considered to link the restoration of voting rights to progress on other human rights issues, not limited to Ukraine, and in particular to addressing all concerns about political prisoners.

Proposal V: Azerbaijani chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers

On 14 May, Azerbaijan assumed the six-month chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers. There is consensus among human rights NGOs that the situation with political prisoners has markedly deteriorated in Azerbaijan. This has also been publicly confirmed by various institutions of the Council of Europe. On 29 April, the Council’s Human Rights Commissioner Nils Muiznieks issued a statement on Azerbaijan, in which he condemned “unjustified or selective criminal prosecution of journalists and others who express critical opinions.”

On 22 May, Secretary General Thorbjorn Jagland published an op-ed in European Voice, in which he conceded that Azerbaijan was “known in Western capitals for stifling journalists and locking up opposition activists” and maintained that the Council of Europe was not blind to violations. The same day, ECtHR issued a judgment saying that the Azerbaijani authorities had arrested opposition leader Ilgar Mammadov to “silence and punish” him for criticising the government.

On 23 May, PACE President Anne Brasseur spoke in Baku, mentioning a “more than worrying state of affairs” in Azerbaijan, criticising the deterioration of freedom of expression, assembly and association, and calling on the government to release Ilgar Mammadov.

There is a consensus on the seriousness of the problem. There should now also be an appropriate reaction. One clear measure to be considered now would be to hold no Council of Europe meetings and events in Azerbaijan until Ilgar Mammadov, on whom the ECtHR has already ruled, is released.

Secondly Azerbaijan should officially agree to the appointment of a new PACE rapporteur on political prisoners and commit itself to cooperation.

Thirdly, the Secretary General and the Committee of Ministers should establish an Expert Commission as outlined above.

Proposal VI: an EU visa panel for human rights violators

The European Union has the power to sanction human rights violators. One type of sanctions (“restrictive measures”) are travel bans. Traveling to the EU is not an inherent right. It is a privilege that governments are free to deny. Sanctions can be proposed by member states and the High Representative for Foreign Policy, who can also act together with the European Commission.

The body responsible for imposing sanctions is the Council of Ministers. It does so by adopting – unanimously – a document called a “decision”. For travel bans, no additional legislation is necessary, and member states are obliged to directly implement the Council’s decision. Travel is a privilege, not a right. The EU needs to develop a forward-looking policy of denying entry and visa to human rights violators from Russia, Azerbaijan and other states.

To do this, member states could sponsor an independent commission of senior former judges, who would make annual recommendations to the Council of Ministers on who should be barred from entry.

This proposal avoids two pitfalls: it is not summary justice and it provides a mechanism for appeal. The independent commission would review its recommended blacklist annually, providing room for appeal. The whole process would also ensure transparency. This would increase pressure on EU governments to act, spur debates, and create a credible process that human rights defenders can use.

Conclusion: a campaign “2015 For a Europe without political prisoners”

Many of the most respected human rights organisations have their roots in campaigns on behalf of political prisoners: Amnesty International (the 1961 letter by Peter Berenson on “The forgotten prisoners”), Human Rights Watch (the Helsinki committees to support dissident in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union).

After the end of the Cold War it seemed for a short moment as if this particular problem no longer haunts Europe. Now it has returned. This is a test of the ability and compassion of European civil society, and of the organisational capacity of human rights defenders. A reactive approach is clearly no longer enough.

Combined efforts pay off. Concrete initiatives and proposals can be brought together under the banner of a Europe-wide campaign “2015 For a Europe without political prisoners.” Such an effort would be a joint effort of different independent human rights NGOs. The strategy could encompass all these various elements:

– highlighting stories of individual victims better;

– mobilising support for victims, their families and lawyers;

– mobilising think tanks and NGOs to monitor and analyse PACE and its members;

– taking back and using existing mechanisms in the Council of Europe;

– setting up a new mechanism in the Council of Europe to look into systemic imprisonments on political grounds in member states,

– institutionalising a process for visa bans for human rights offenders by the EU.

In accordance with Article 17 of the Statute of the Council of Europe: “The Committee of Ministers may set up advisory and technical committees or commissions for such specific purposes as it may deem desirable.”

PACE Resolution 1917 (2013) “The honouring of obligations and commitments by Azerbaijan”, 23 January 2013, para. 14.

Nils Muiznieks, “Freedom of expression, assembly and association deteriorating in Azerbaijan”, 23 April 2014.

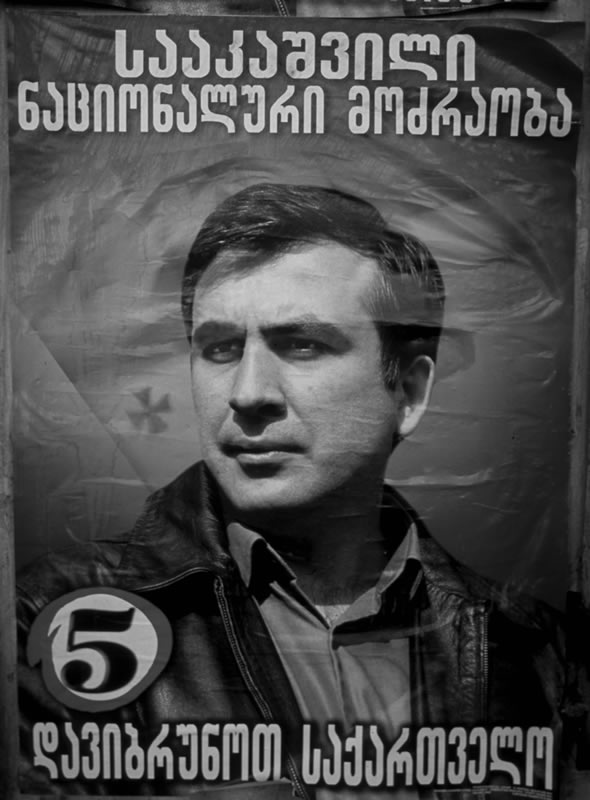

Ilgar Mammadov and Tofiq Yagublu, two political prisoners in Azerbaijan

A few days ago a relative of another political prisoner in Azerbaijan, Tofig Yagublu, forwarded me this appeal:

“I have been sentenced to prison term on absurd charges since I fight for democratization of Azerbaijan, for its transformation into the part of the progressive world. So that you have an idea about absence of any justification for charges against me, I would like to state that, those charges have as much relevance to you as it has to me.

Due to aggressive actions of Russia against Ukraine the humanity is on the brink of its another tragedy. It is a problem of lack of democracy. Russia’s complacent, illogical and unfair actions are due to lack of democratic society and democratic government formed in accordance with popular will. Would Russia be able to act complacently and carelessly like this, had it had democratic societies in the countries surrounding it?

Therefore, one of the most effective ways of helping Russia is seriously supporting democratization process in surrounding former soviet countries. The Azerbaijani authorities are illegitimate and corrupt. The amount of money stolen by these authorities from the people is way more than the state budget. There have not been any free and fair elections in Azerbaijan since Aliyevs came to power in Azerbaijan. The OSCE ODIHR opinion on the presidential elections held in the autumn of 2013 was the most critical and strict among the opinions stated until present. But even this critical evaluation is lenient compared to the objective reality.

The statements of the authorities with regards to absence of democracy and human rights problems in Azerbaijan is similar to what the USSR leadership used to say on the same topic, and to what the North Korean leadership is saying now. The incumbent government is using energy resources and its important geographical location to refrain from carrying out its international obligations on democracy and human rights. Unfortunately, they have been successful in this until present.

Take into consideration that, political parties and civil society organizations fighting for democracy in Azerbaijan unambiguously see the happy future of Azerbaijan in integration to the West, to EU and NATO. Under such circumstances, the interests of the Azerbaijani people and the progressive world will be ensured more effectively and in a more guaranteed way, unlike in case of existence of the regime, which is staying in power through the Kremlin’s support.

Therefore, it is obvious that, significant pressure on the incumbent regime to start democratic reforms in Azerbaijan is an objective necessity. Under such circumstances, carrying out of the June session of OSCE PA in Baku is withdrawing in front of the Azerbaijani authorities, which have closed the Baku office of this organization and have declared war against the Warsaw bureau due to its negative opinion on the elections. It is difficult to understand this step.

The First European Olympic Games will be held in Baku in the summer of 2015. Shortly after this competition the parliamentary elections will be held in the country. It is very illogical and unfair that, such an event will be held in a country which lacks basic freedoms, prisons of which are full of political prisoners, where free press is mercilessly strangled, on the brink of another election fraud. Those Games shall be boycotted. Until the start of real democratic reforms under the monitoring and guarantee of the international organizations in Azerbaijan, all possible sanctions shall be applied against the Azerbaijani authorities.

Tofig Yagublu, political prisoner 17.03.2014 “

The Palace of Europe in Strasbourg

The Palace of Europe in Strasbourg Council of Europe

Council of Europe

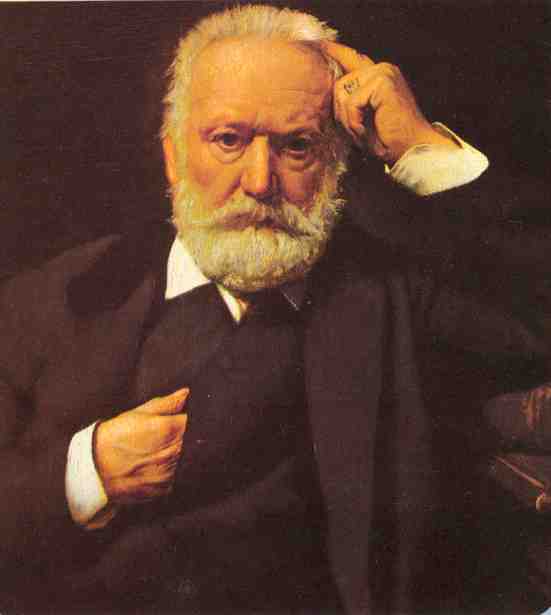

Viktor Hugo, writer, author of Les Miserables and visionary who wrote the

Viktor Hugo, writer, author of Les Miserables and visionary who wrote the