Navalny’s health is deteriorating rapidly. Is Russia’s president letting his most important opponent die in custody? If the Council of Europe does not act now, it will make itself superfluous.

Hardly anyone shaped post-war Europe as much as the Frenchman Pierre-Henri Teitgen. And hardly anyoneis so forgotten today.

Teitgen fought in the resistance against Hitler. He was arrested by the Gestapo and narrowly escaped the concentration camps. After 1945, he rose to become France’s Minister of Information and Justice under de Gaulle and helped found the daily newspaper “Le Monde”.

Above all, Teitgen was one of the initiators of the Council of Europe, an association of European states whose most important body is the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg.

A question of life and death

The Holocaust was on Teitgen’s mind all his life. “Democracies do not become Nazi states overnight,” he said. “Evil spreads cunningly. Step by step, freedoms are suppressed.”

Teitgen and his comrades-in-arms wanted to ensure that such a catastrophe would not happen again in Europe. The Council of Europe was supposed to prevent democracies from turning into dictatorships. It is one of the great achievements of the post-war period. Now, however, it is about to become irrelevant.

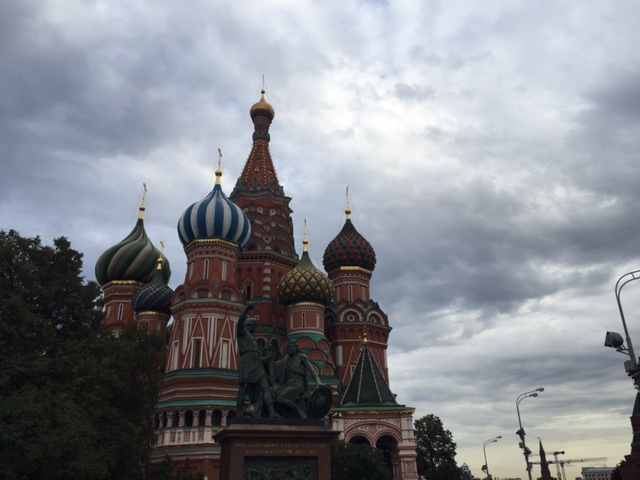

Although the number of members in the Council of Europe has grown from ten to 47 in recent decades, many states no longer feel bound by its word. Russia, in particular, is systematically undermining the body.

The Kremlin, like all other Council members, has officially committed itself to implementing ECHR rulings. In reality, however, it mostly ignores them. For a long time, this was a nuisance for the Council of Europe. Now it is a matter of life and death.

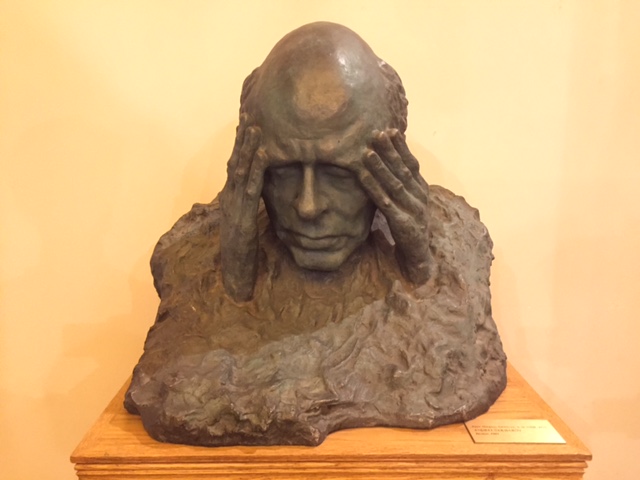

Russia’s most prominent opposition figure, Alexei Navalny, has repeatedly appealed to the ECHR, a total of twenty times, more than any other citizen. As recently as February, the ECHR ordered that Navalny be immediately released from prison in Russia. However, the Russian regime has defied this ruling as well.

Everything depends on Germany

Navalny, who only last summer narrowly survived a poisoning by the Russian secret service, has since gone on hunger strike. His health has deteriorated dramatically. His lawyers warn that he could die any day.

The Europeans have a number of options to influence Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. They could impose sanctions against his regime, Germany could stop the construction of the Nord Stream pipeline.

But the Council of Europe in particular has seldom been so challenged. It must exert pressure on Moscow. The „European Stability Initiative“ (ESI), a think tank based in Berlin, shows how.

In a recent paper, Gerald Knaus’s experts at ESI argue that the Council of Europe could issue an ultimatum to Russia with a two-thirds majority in the Committee of Ministers. If the Kremlin does not release Navalny, Russia could be temporarily expelled from the Council of Europe. It would be a sign that Europeans are not willing to accept Russia’s internal and external aggression without further action.

Germany is now likely to be the main player in the dispute with Moscow. The German government still holds the chairmanship of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe until the end of May. In a speech to the Council of Europe on Tuesday, German Chancellor Angela Merkel promised to stand up for Navalny. „We are very worried,“ she said.