…. continued from Peddling Ideas Around Schuman I (Brussels in January: Coweb)

EPC and the future of screening

Graham Avery Judy Batt Jacques Rupnik

Institutions like EPC are another fixture in the Brussels policy landscape. I have come here quite often in the past, for debates and presentations. Last year I was invited to join EPC’s international advisory board. This time the occasion to come was the ECP “task force” on the Balkans.

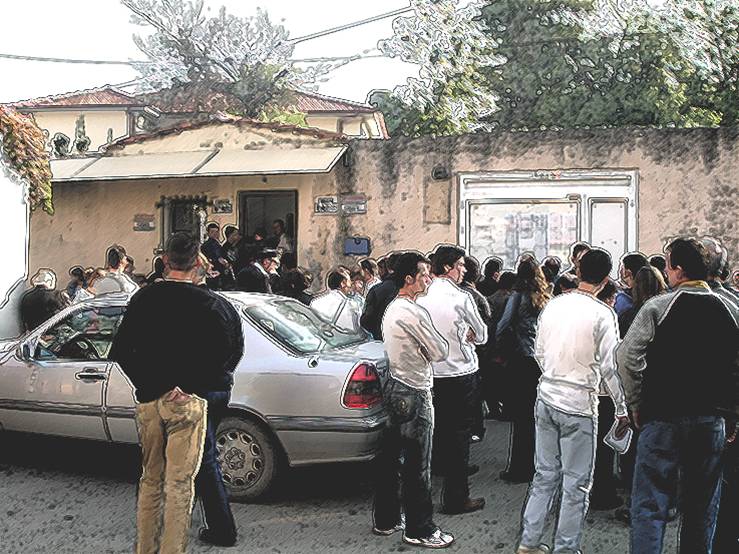

EPC is, to those not familiar with Brussels, the equivalent of an intellectual club for Brussels policy-makers: they can come to listen to arguments and debates without really having to leave their offices (the Residence Palace, where EPC is based, is right across the road from all the main EU buildings). But EPC also aims to generate ideas. This is why a small group of Balkan experts had been invited to come together a few times this year and debate. Chaired by Graham Avery, some 10 experts took up the offer.

Again Alex and myself distributed our most recent reports. Again we tried to challenge some conventional wisdoms about the Balkans (particularly about Bosnia this time). And once again we had a specific proposal which we sought to put up for debate: the notion that screening for all the countries of the Western Balkans should begin later this year, even before the start of full accession negotiations. For details on this proposal see my next entry on Rumeli Observer; let me make a more general point about the spreading of policy ideas here.

My first observation: policy proposals are often most effective when their origin is forgotten. One of the attributes of a successful think tank is not to be possessive about “ideas”: the more an idea, analysis or policy proposal becomes part of a new “received wisdom” the more likely it is to be adopted. A policy proposal for real change needs to become part of a new consensus. For this to happen the gatekeepers in public policy debates (journalists and policy analysts) need to find it convincing.

The EPC meeting was a gathering of such gatekeepers. There are others in other places. In fact, like a wandering circus, seminars and conferences on the Balkans take place across Europe every few weeks (or more). I sometimes wonder why “the future of Kosovo” needs to be discussed by a similar crowd of people every other month in another European holiday destination (Paris, Athens, Rome, Vienna ….). However, in the end the intellectual activity that takes place (or does not) at these events matters. This is true for better or worse: when such meetings generate no ideas, or the wrong ones, the consequences will also usually be felt before long …

Compared with other sumptious gathering this EPC task force meeting is a frugal affair. A small group, exchanging ideas over sandwiches, with the vague notion to “contribute to the debate” on the future of EU policy. What exactly we would contribute is left open, it is only agreed that there would be some paper at the end, still to be determined. Participants prepare presentations for each other and then discuss them. I volunteer for a presentation in February on lessons for the Western Balkans from the Eastern Balkans.

Who are the members of this group? There is the chair, a former senior commission official in charge of enlargement, Graham Avery. There is Judy Batt (now based in Paris), Jacques Rupnik (from Paris), Tim Judah (based in London), and others. These are all familiar faces. I had recently met Jacques in Tirana at the Albanian ambassador’s conference (see The gate-crashing principle), Judy in Belgrade a few months ago and Tim in Pristina. I narrowly missed him at an event in Georgia, and would have seen him at another event in DC next February, if I would have accepted the invitation. This indicates the nature of this loose network of Balkan watchers: as a group, people who work on the Balkans in policy institutes across Europe probably meet at least as often as their political counterparts from European foreign ministries. And like them, the thing they do is talk.

Does this kind of talk matter? There are many bad conferences, badly prepared speakers, repetitive moments at conferences around Europe. However, listening to Jacques explain the latest thinking in France about the future of enlargement, hearing Tim’s first hand information about his latest encounters with diplomats and politicians in Belgrade, learning from Judy about whatever her latest trip to the region revealed about the mood in Belgrade or Podgorica is always of enormous benefit. So is seeing their reactions to concrete ESI proposals.

What does Lajcak really want to achieve in Bosnia? (Judy has become one of his outside advisors). What is Tim’s latest impression of the political dynamics in Belgrade? (where Tim goes all the time). How genuine is the new French rhetoric about enlargement? (Jacques explains that it is real, having discussed this on a panel recently with the Minister for Europe in Paris, Jean-Pierre Jouyet). How might the idea of an early screening in the Western Balkans be received by the Commission? (I note with relief that Graham Avery finds the idea interesting). Etc …

Malcolm Gladwell has written about the “law of the few” in the spreading of ideas, distinguishing between connectors, mavens and salesmen. Connectors are people who know lots of people. Salesmen are those “with the skills to persuade us when we are unconvinced of what we are hearing.” Mavens (a Yiddish word which, Gladwell tells us, means one who accumulates knowledge) are people “who read more magazines than the rest of us, more newspapers, and they may be the only people who read junk mail”:

“What sets Mavens apart, though, is not so much what they know but how they pass it along. The fact that Mavens want to help, for no other reason than because they like to help, turns out to be an awfully effective way of getting someone’s attention.”

Mavens are “really information brokers, sharing and trading what they know.” This is perhaps the best way to describe this EPC meeting: as a gathering of Balkan mavens.

Connectors in Brussels

L. Keith Gardiner notes in an article written in 1989 (Dealing with Intelligence-Policy Disconnects) that policy analysis “cannot serve if it does not know the doer’s minds; it cannot serve if it does not have their confidence.” He also writes that

“most policy-makers probably would welcome analysis that helps them to develop a sound picture of the world, to list the possible ways to achieve their action goals, and to influence others to accept their visions.”

This calls for “colorful, anecdotal language”:

“analysts strongly prefer to transmit knowledge through writing, because only writing can capture the full complexity of what they want to convey. Policy consumers, however, tend to seek what can be called “news” rather than knowledge; they are more comfortable with a mode of communication that more closely resembles speech.”

This, then, is the third reason to come to Brussels (and do so regularly): one-on-one meetings with EU officials, with friends, like Heather Grabbe, from the cabinet of Olli Rehn, who is in charge of Turkey; old friends like Michael Giffoni, now heading the Balkan department in the Council (we worked together in Bosnia almost a decade ago). The Balkan team in the Slovenian permanent representation in Brussels. Ben Crampton, working on Kosovo in the council, another old hand from the Balkans (whose father, one of the leading historians on South East Europe, I had known in Oxford). Stefan Lehne, the director for the Balkans and East Europe in the EU Council …

Until the next trip …

The fourth task, finally, is the real bread and butter of our work, without which there would be nothing to share, no ideas to present, and no reputation to open any doors: sitting and grappling with the draft of future ESI reports with Alex. Sitting in her apartment in Ixelles we prepare a short intervention for the upcoming debate on the future mandate of the OHR (which will be discussed at the PIC at the end of February). We discuss the Austrian debate on Turkey (a report which has been depressing me for a few months now). We talk through in detail our upcoming report on the German debate on Turkey. And then there is another amitious report on Central Bosnia to finish ….

In the end the whole trip to Brussels lasts a mere three days. As I leave a new long list of dates has been fixed which imply coming to Brussels: a presentation in February to the EPC taks force; a presentation of the Balkan film project with the Slovenes; a presentation on energy policy in the Balkans at EPC; a meeting with Olli Rehn; another one with Javier Solana; a brainstorming with Peter Feith, the future head of the International Mission in Kosovo, and his senior team. Thus the cycle of trips to the European capital never ends …