Reading what some of Turkey’s best journalists – and many friends – describe as happening in Turkey right now – while sitting in France and reflecting on how this country’s very similar polarised and fractured politicaul culture changed in past decades, is an interesting experience. So before I am heading back to Istanbul here is a view from France: all this might be falsified within days: but as a momentary glimpse into the past and future of two proud nations, but perhaps this is interesting nonetheless. Here is why.

It is to France that Turks looked so often in the past when they built their state. It is to the French ideal of an elected but then imperial presidency that Turkey’s leader, prime minister Erdogan, may have unconsciously aspired as his plan for the next years. And it may well be that the most fruitful analogy for what happens in Turkey today is May 1968.

The popular protest revolt in May 1968 took place at a time of the fastest and most sustained period of economic growth in France. There was a youth bulge as the post war baby boomers reached adulthood, with universities expanding rapidly. There was an elected, conservative and increasingly autocratic president, who had gone from election victory to election victory, and was seen by his supporters (and saw himself) as saviour of the nation from the instability of a previous regime (in France the 4th Republic with ever changing governments, in Turkey the 1990s). But he also had lost touch with a young and urban population uninterested in the battles of the past that define him. The protestors cared less about France leadership role in the world and its prestige than about participation. They wanted a society attuned to different values than their president did, more diverse, less deferential. He, however, could not understand how – having restored his nation’s prestige and leading it to stable government and steady growth – he could be thus challenged.

As protests started over seemingly small issues (students in conflict with the university in Nanterre) heavy-handed responses by the police inflamed them and they spread like wildfire. The president is confused, outraged at this challenge; he first goes abroad, and then turns to the one answer he believes will resolve the fight over legitimacy. It is one he has chosen before in the face of challenges: early elections.

This dramatically changes the atmosphere, and indeed: his party wins the elections, again, as no clear opposition emerges among other established parties to channel the energy of the street into electoral change … and as the silent majority in this conservative country fears anarchy and chaos more than it welcomes dramatic change.

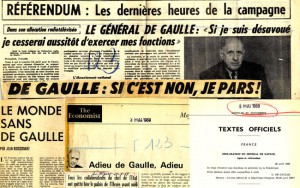

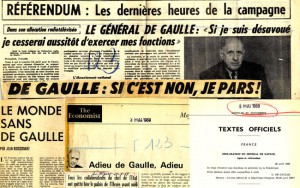

But for De Gaulle this broad challenge still has profound consequences. He cannot understand how a nation he has served can be so ungrateful. A year later De Gaulle puts himself behind a referendum over a constitutional issue. In this referendum it turns out that his former close collaborators are lukewarm or oppose him:

“De Gaulle announced that if the reforms were refused, he would resign. The opposition urged people to vote no, and the general was equally hindered by popular former right-wing prime minister Georges Pompidou, who would stand as a presidential candidate if de Gaulle were to leave, reducing the fear of a power vacuum felt by the right-wing gaulliste electorate. Also, former finance minister Valéry Giscard d’Estaing declared that he would not vote yes.”

1969 turned into a referendum on the president himself and on his style. He looses and resigns.

As everybody gazes into a crystal ball, and nobody knows, this is certainly an interesting analogy. Who would be Turkey’s Pompidou in this scenario: The convervative successor of the autocratic father-of-the-nation president, less polarising than his predecessor?

The fact that the parliamentary opposition in France was divided, and ambiguous on where it stood on democracy itself, with its roots in an undemocratic ideology (French communism) also undercut it. Fill in the blanks in the analogy for Turkey.

Is it also true that super-centralised regimes with imperial (albeit elected) leaders – here the France of the 60s, there the Turkey of today – are most vulnerable to being out of touch when there is rapid generational change – and yet also find it hardest to transform changes in the mood into changes at the ballot box.

All this assumes that the response eventually chosen by the Turkish government remains “European”, becoming of a Council of Europe member, and will not be inspired by the real autocracies in Turkey’s neighourhood; in other words, it is not resolved by an escalalation of violence and repression. Of this I still remain confident: Turkey is not Russia or Azerbaijan, and the AKP is not United Russia or the party of Ilham Aliyev. The most interesting issue for how things will develop might now well be the calculations within the broad conservative majority and its various leaders – in office and outside.

PS: A quick reader for those who are interested in the analogy: http://martinfrost.ws/htmlfiles/paris_1968.html.

PPS: Two of the best Turkish journalists and their observations of events are here. Cengiz Candar: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/06/turkey-velvet-revolution-istanbul-protests.html. Amberin Zaman here: http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/06/istanbul-protests-who-are-protesters-turkey.html.

Amberin wites: “Be it through restrictions on alcohol or disregard for the environment, people who do not share Erdogan’s worldview are being made to feel like second-class citizens. The sentiment is especially strong among the country’s large Muslim Alevi minority whose long-running demands for recognition continue to be spurned much as they were by past governments. Hard-core secularists who massed in the district of Kadikoy, a CHP stronghold on the Asian side are keen to paint the protests as a backlash against the “Islamist” AKP. It’s not just CHP supporters who feel their lifestyles are being infringed upon. Conscientious objectors, atheists and gays, almost anyone who falls outside the AKP’S conservative base is feeling squeezed. The majority, however, are sick of old-style politicians and their tired ideas. So where will they go? The question is growing ever more pressing in the run-up to nationwide local elections that are to be held next year.”

She concludes: “Turkey is not on the brink of a revolution. A Turkish Spring is not afoot. Erdogan is no dictator. He is a democratically elected leader who has been acting in an increasingly undemocratic way. And as Erdogan himself acknowledged, his fate will be decided at the ballot box, not in the streets.”