I gave the keynote speech (“Orderly migration and social cohesion”) at the annual conference of the German asylum agency BAMF in Nuremberg.

More on the event on the ESI website.

I live in Berlin. It is from here, the very centre of modern Europe, that I observe the world. Some of these observations I will share on this blog.

I gave the keynote speech (“Orderly migration and social cohesion”) at the annual conference of the German asylum agency BAMF in Nuremberg.

More on the event on the ESI website.

Also available in Turkish:

06 Mart 2016 Tarihli Davutoğlu-Merkel Buluşmasında Ne Oldu?

There has been a lot of speculation about the (allegedly) surprising, for some even shocking, proposal Turkey made on 6 March in Brussels at a meeting in the evening at the Turkish embassy between Ahmet Davutoglu, Angela Merkel and Mark Rutte, on the eve of the European leaders discussing refugees with Turkey on 7 March. EU Observer wrote:

“The bombshell came during lunch when a new plan, to the surprise of many EU leaders, was put forward by Davutoglu. Only a handful had previous knowledge of the plan, and only a few moments before. It appeared that the plan – the quid pro quo mentioned above – has been discussed by Davutoglu, Merkel and Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte on Sunday evening at the Turkish EU mission in Brussels.

A source close to Merkel now says that she discovered the plan at the meeting and only discussed it with Davutoglu and Rutte to make it workable. But for most of the participants who discovered it on Monday, she was the brain behind the Turkish paper. “Stop saying it’s a Turkish plan, they haven’t written it,” an angry official from a small member state told a group of journalists.”

In fact, the official quoted here (and many others, including European leaders such as French President Francois Hollande) was wrong.

Turkish officials had discussed ideas similar to those Davutoglu presented to Merkel and Rutte – which were public since September 2015 – for a long time; ESI reports developing these proposals had been translated into Turkish many months before; and ESI analysts have presented these ideas in Istanbul and Ankara numerous times. In early 2016 we made another concerted effort to promote these ideas in Turkey. At the end of February we sent a series of letters to Turkish officials and ambassadors, followed by more meetings, arguing that it was in Turkey’s interest to adopt the Merkel-Samsom Plan. Letters like this one:

29 February 2016

Dear … ,Please find a short paper with ideas, following up on the things we discussed. I hope it is useful.Those in the EU who say Merkel has to give up on her idea to work with Turkey are growing stronger. Merkel remains strong in Germany. If there is a real breakthrough in the next days and weeks she could retake the initiative in Europe – but only if joined by Greece and Turkey. This would benefit refugees, a liberal EU, and Turkey all at the same time.One additional issue we discussed was the paragraph in the paper “Key elements of a resettlement/humanitarian admission scheme with Turkey” that was not agreed upon yet. It would be much better to have a direct link to readmission from Greece, like this:“The Member States participate in voluntary resettlement on the assumption that Turkey fully implements the existing readmission agreement, agrees to be considered a safe third cojntry by Greece, and that it will cooperate with Greece and the EU efficiently and speedily.”These are not subjective criteria; they would depend on Turkey – assuming that Greece is helped now to handle readmission.It would be great to talk soon. Lets hope the next week brings a breakthrough. The key for this lies in Berlin and Ankara.Best wishes from Istanbul,Gerald Knaus

Together with such letters we sent policy makers the following short paper with concrete suggestions:

Suggestions for the Coalition of the Willing and Turkey

European Stability Initiative – 29 February 2016

There is a dramatic loss of trust around Europe in current policies on the refugee crisis. However, all the alternatives to close cooperation with Turkey –reducing the refugee flow in the Balkans as decided at the recent Balkans summit in Vienna or pursued already for a long time by the Visegrad group led by Hungary – will not work. Failure only benefits the illiberal, pro-Putin, anti-refugee and anti-Muslim coalition across Europe.

There is a need for a strategy that:

– turns a chaotic and disorderly process into an orderly one,

– supports Turkey immediately through humanitarian resettlements

– supports Greece for it to be able to readmit people to Turkey,

– gets a commitment from Turkey to accept readmitted people speedily from Greece,

– observes international, European and national legislation on refugees.

What has to take shape in March

– A process of orderly resettlement of Syrian refugees from Turkey, beginning in March, of 900 a day, every day (27,000 a month, 108,000 in four months, 324,000 a year). This will continue for the foreseeable future – like the Berlin airlift, which had no end date.

It is crucial that this process begins in March. The fewer intermediaries are involved, the better. Each nation that participates should examine its own legal provisions, see how they can be adapted to this emergency, and how soon they will be able to take people. The perfect is the enemy of the good.

Reach agreement with Turkey that 900 a day for a year is the target but also the minimum goal; if there are further huge waves of refugees in the future from Syria it may be extended. It is a floor, not a ceiling.

– Readmission to begin, ending the movement along the Western Balkan route in the Aegean. Turkey to commit to take back (in principle) everyone who reaches Greece after the day on which the first group of 900 is resettled from Turkey.

Change the incentives for refugees. Readmission from Greece to Turkey and relocation from Turkey will make the crossing of the Aegean pointless and redundant. The better and faster it works, the less people Greece and Turkey would need to deal with four months from now.

What is needed:

– Greece prepares where to hold and process any claims of those to be returned to Turkey.

Setting ambitious/realistic goals, in a permanent working group supported by the coalition of the willing and with Turkey present. Can Greece manage to return all North Africans immediately in March? Can it do the same for all Pakistanis? And some from other groups for maximum impact?

– Strong and simple communication: “Greece considers Turkey a safe third country. Turkey accepts that it is a safe third country for Greece. Your asylum applications will be declared inadmissible. Do not risk your lives, or the lives of your children.”

Very important: images of significant numbers being returned from Greece to Turkey; and of people returning from Turkey to their home countries.

– Turkey does not want to readmit Syrians.

Agree instead that until the summer Greece will not send back Syrians. Then, by the summer, once Ankara (and Syrian refugees) see that the resettlement to the EU is serious and substantial Turkey will start taking back also Syrians. Turkey will want to first see that the EU does help with Syrian refugees directly and in a substantial way. This will coincide with visa free travel in place for Turkish citizens.

– Greece does not have the capacity to hold people and to process the asylum claims of those who decide to make one in Greece instead of being returned right away. This has to be build up.

– Turkey and Greece need to review the protocols and practices of their existing readmission agreement (for instance: it seems that the “accelerated procedure” of 7 days for Turkey to deal with Greek claims is only applicable to the land border; the normal procedure is 75 days. It should be 5 days for every case; etc.).

– Turkey and the EU need to develop a strategy to provide incentives to as many as possible of those who are returned to go on and return voluntarily to their home countries – vouchers for North Africans and Pakistanis to fly back right after they return to Turkey, etc …

– For those who decide to then apply for protection in Turkey and become asylum seekers there: Turkey needs to be ready to deal with this. And should get immediate support to build reception facilities.

Some issues to address

TURKEY: committing to larger and faster readmission from Greece is not easy politically. The history of negotiations over the Turkey-EU readmission agreement testify to this. And yet it is crucial: no resettlement is sustainable without such control in the Aegean.

There is, however, more that the EU can do to help Turkey – and convince the Turkish public:

– The European Commission begins right away the process of lifting the Schengen visa requirement for Turkey, launching the process to amend regulation 539/2001. This legal process always lasts a few months.

But the EU should hold out a concrete promise to Turkish citizens with concrete dates:

“If Turkey implements the existing readmission agreements with Greece in full and agrees to take back all new arrivals from 15 January 2016 and implements all requirements from the visa roadmap concerning the rights of refugees and asylum seekers in Turkey until 30 April, Turkish citizens will be able to travel without a visa to the EU as of June 2016.”

If this is backed by the Commission and Germany and others, this would be a powerful signal.

This should be targeted at the two key requirements Turkey must meet:

fully implement the readmission agreement with Greece,

be a safe third country and fully implement its 2013 law on foreigners.

There is no good reason at all to either link visa liberalisation to the EU-Turkey readmission agreement (rather than to effective readmission from Greece) or to delay it until October. The EU needs Turkish support now. And Turkey should get visa free travel as soon as possible.

– The EU offers to delink visa liberalisation and the EU-Turkey readmission agreement provision for third country nationals (which was supposed to enter into force only in 2017, and was then brought forward to June 2016).

The EU-Turkey Readmission Agreement is the worst of both worlds: Under this agreement in theory everybody who reached the EU from Turkey in the past five years could be returned. (Article 2 – Scope) There is no provision that says only people who arrive in the EU after a certain date qualify. At the same time the agreement does not work, beyond what already exists in the Turkey-Greece Readmission Agreement, since none of these people reached the EU directly from Turkey (they left Greece and re-entered the EU from Serbia).1

GREECE: For Greece to send larger numbers of refugees for readmission to Turkey is a major administrative challenge. In addition, most people in Greece do not believe Turkey will take people; many (including people close to Tsipras) doubt that the EU will resettle serious numbers from Turkey. I heard this many times in Athens recently.

Due to the above, for Greece the following is important:

– Greece sees resettlement from Turkey taking place.

– The EU will help Turkey concretely to improve conditions for asylum seekers and Syrians offered protection in Turkey (as part of the 3 billion package, or through direct bilateral aid).

– Germany, the Netherlands and others will strongly oppose any talk of Greece being suspended from Schengen.

– The European Commission and major EU members will not support any efforts to build a wall across the Balkans north of Greece to keep refugees from moving on.

– The strategic (and achievable) goal of German-Dutch policy is to have no Balkans route at all. But until the readmission-relocation scheme starts to work in the Aegean, the route should remain open.

On the key practical issue of preparing for and implementing readmission Greece will receive strong support from Frontex and EU member states.

The case to suspend relocation

Putting an end to the current relocation scheme from Greece (and Italy) would make all the above steps easier to reach. It would send a strong signal that Germany and the EU have learned from the experience of recent months. What is now proposed is different (and as opposed to previous relocation, it will work).

The basic argument is here: Relocation – even when it works it fails.

See more here: ESI Post-summit paper: The devil in the details (29 November 2015)

An early suspension of this would achieve other positive effects:

– The limited Greek administrative capacities are better focused on preparing for readmission – the same is true for technical help to Greece.

– This would make it easier to enlarge the Coalition of the Willing. Every country should be invited to take voluntarily at least the same number of Syrian refugees from Turkey as they would have taken from Greece.

END

So was the breakthrough on 6 March also a surprise for us? Yes, it was.

Since September 2015 ESI had argued – in presentations and meetings – that Turkey should offer to take back everyone who reaches Greece and that in in return the EU should resettle substantial numbers of refugees directly from Turkey. However, by early March we had concluded that Turkey was not in fact prepared to take back Syrians before summer 2016 and before there was serious resettlement and visa liberalisation was within reach. It was a surprise for us, therefore, to learn that on 6 March Turkey was ready to embrace the whole Merkel-Samsom Plan immediately … a bold move by the Turkish prime minister.

What was not a surprise at all was the fact that in return Turkey would demand that visa liberalisation be realised before summer 2016 … we had been arguing for this for months already in every one of our meetings in Ankara and Istanbul.

‘Ik was in Izmir en zag: we hebben geen tijd meer’

I was in Izmir and saw: we have no time anymore

The article explains how Diederik Samsom [leader of the PvdA, the Dutch Labour party], on a trip to Turkey that started on 5 December 2015, went on a patrol with the Turkish coast guard and realized that things had to be done differently. From this emerged his new plan to stop the flow of refugees. Prime Minister Rutte immediately called it “Plan Samsom”, with Samsom commenting in response: “Mark does this always very smartly.”

The article notes that it is the height of the waves at sea that determines how many people cross, “not our action plans”. He writes, summarising Samsom’s view, that “we need to move towards a system where the crossing is pointless”.

The article continues that “the district of Izmir in Turkey where refugees and smugglers meet” is a small Syria. Diederik Samsom realised that “this is totally uncontrollable. The squares, the bazaar, the restaurants and the shops, they form a single market for illegal travel to Europe elusive to police control.” The same night Samsom met motivated and frustrated police and border guards in Cesme, opposite the Greek island of Chios. The article quotes Samsom about the island: “You can almost touch it, it is so close”. There is a 20 kilometer-long coastal road. The author quotes Samsom:

“A beautiful coastline with little beaches, with the same scene on each of these beaches. Refugees come running down goat paths, carrying folded rubber boats and luggage. On the beach, [the boats] are inflated quickly, by hand or with air cartridges. Within 10 minutes they leave. The only one that can stop them is the coastguard. But it cannot be everywhere at once.”

“The night when I was there, twenty boats left. We did not manage to catch even one of them. The following day there was a picture in the newspaper of two drowned children, on one of the beaches where I had been.”

When Samsom returned to The Hague he realized that the long-term idea – that asylum claims are handled outside Europe – had to be brought forward dramatically. Samsom elaborated:

“For me it was clear: we do not have years. This should be put on track before the new refugee season, this spring. On the Turkish coast, a kind of highway to Europe has been built. With a complete infrastructure of smuggling networks and – since the Turkish authorities have banned the import of Chinese dinghies – illegal boat factories. This attracts more and more people, especially North African men. The refugee stream will double easily.”

A few days later, Samsom was sitting with Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte.

“I told him, it is an illusion to think that if we deploy the coast guard, Frontex in the middle and if we pay the Turkish police, a solution will be found. All these measures contribute, they are needed, but they are not sufficient. The height of the waves at sea determines how many people cross, not our action plans. We need to move towards a system where the crossing becomes pointless. As long as the crossing offers a chance, however small, people seem willing to even lose their children on their way.”

The article notes that the plan that Samson put to Rutte has the charm of simplicity:

“The asylum request of everybody that arrives on Chios, Lesvos, Kos or any other Greek islands is declared inadmissible because [the refugees] come from Turkey, which is a safe country for refugees. They will be returned back there by ferry. However, Turkey will accept them only if large numbers of recognized refugees can go to Europe from Turkey in a legal manner. [There must be] a legal asylum route for a couple of hundred thousand refugees per year. Of this I [Samsom] convinced Mark [Rutte]. On the same day, he called it immediately the Samson plan. Mark does this always very cleverly, in this way we commit to each other.”

More excerpts from the interview with Samsom:

How many refugees can go yearly to Europe from Turkey?

The Turkish say 500,000, as many as possible, but that’s not going to happen. Between 150,000 and 250,000 per year …

Will EU countries receive compulsory quotas?

That was the next issue and we worked on it last month. At first you think: of course everyone has to contribute. However, we did this experiment in the EU last summer with the redistribution plan for 160.000 refugees who were already in Italy and Greece. I remember that I thought at the time: good, those who were not ready to cooperate were outvoted. No single country can block the solution anymore. However, they can actually undermine it and they managed to do so. Compulsory quotas do not work.

So it will happen on a voluntary basis?

Yes. There will be a little table with all the Member States and then there will be many empty spaces after their names. There may be 18 empty spaces, and in ten spaces there will be numbers. I am in intense contact with some of these ten because there are Social Democrat in government. These are Germany, Austria and Sweden, all countries that, just like the Netherlands, have large numbers of refugees. Countries that are convinced that the current influx is unsustainable. The welfare state, which all Social Democrats promote, will collapse if we do not control the refugee flow. In the worst case scenario, only these countries will cooperate with others such as France, Spain and Portugal. If there will be 250,000 legal refugees, Netherlands will have to accept 20,000-30,000. This is considerably fewer than the 58,000 who came last year.

So, even if only a small group of Member States participate, the number of 150-250,000 refugees coming to Europe must be respected?

The leading group that participates will have to accept this number. Otherwise, Turkey will not cooperate.

Then the rest will just lean back (and do nothing).

The risk is enormous. You could also lean back, but this does not work. Germany is convinced that a leading group has to step forward, this is how the EU makes progress. Gabriel (leader of German Social Democrats and Vice PM) said to me: ‘Imagine that we take 300,000 refugees from Turkey every year and we Germans are the only crazy ones to do this – we will still be better off than with the more than one million last year.

Thus, the countries that receive the most refugees will continue to do so?

Yes, but the numbers will be lower and more controllable. Now the refugee stream is Darwinism at its best, the law of the jungle. Look at all the men coming from North Africa. If we make an agreement with Turkey on a legal route, it will be only families coming from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia.”

Nonetheless: you reward the countries that disrespect European agreements.

But we will lead a European project. Because the financing will be done with EU money. The costs that the leading group will incur by receiving the refugees will have to be shared by everyone, because this will become the permanent asylum system. I do not have endless patience, even Poland will have to accept it.

You negotiate with Germany, Sweden and Austria. Why not with France, there is also a Socialist government?

France is dodging the issue. PM Valls says ‘intéressant, très intéressant’ when I call and then hopes that I will not inquire further. What I notice is that the French are hoping that this problem will pass them. However, in the meantime Calais is on fire! Paris will need to participate, however, for this some German pressure is needed.

You accept division in the EU on a crucial proposal: that does not look good.

Even if everyone participated, it would not influence the numbers much, the ‘refusers’ are mostly small Member States. It is more a principle than a necessity that ten Syrian families should soon be able to go to Latvia or Czech Republic. We could accommodate these ten families also in the Netherlands, really. What matters is that big countries such as Italy and the UK participate. Receiving refugees and the preservation of the welfare state are fundamental issues. You resolve them only if you dare to look at them from a practical point of view.”

…

Why will Turkey agree? Now 1.5 million leave for Europe, soon it will be only 250,000.

Turkey knows that the situation is unsustainable. It is like a business deal: If you pull someone’s skin over their ears [meaning: paying someone way too much], then that is immediately the last deal. We need each other. The 3 billion Euros that EU has promised to Turkey will otherwise disappear fast.”

Turkey is not a safe country, according to the UN you cannot send refugees back there.

The developments go fast. I see Alexander Pechtold (leader of the D66, whose party supports the ruling coalition) still stand in the debate on the asylum letter, with such a dismissive gesture: who invents this, what nonsense, this will never happen. No one could foresee back then, not even Pechtold, that Turkey would give Syrian refugees the right to work, that their children are even sooner allowed to go to school before they get asylum status. We are not far from the moment that Turkey will receive the status of a safe [third] country. Then it is possible to return refugees to Turkey under the UN convention. Will this be on time? The puzzle pieces need still to be put, however, we have them all in our hand.

Rutte said in January in the European Parliament that the refugee flow will be reduced in eight weeks. Is the Samsom plan a European policy by the end of March?

I consider the chance realistic that this spring a leading group of EU countries will have an agreement with Turkey over a legal migration route for a couple hundred thousand refugees per year in exchange for the direct readmission of everyone that enters via Greece.

What is Rutte doing this week to put forward the plan in Brussels?

The same as me, but with more executive power. Rutte… spends many hours every day working on. He is very hands-on, almost un-European, where often the meeting is the message. Rutte is well placed in order to solve this problem … When Rutte sees that the time is right he will present it in Brussels.”

And if that time never comes?

That is unacceptable. Then every country puts their own fences which will become a meter longer every passing month. Then all Member States set ceilings for the influx of refugees. The result is the worst of the worst: humanitarian dramas and a still more uncontrollable refugee stream. People will not get discouraged by fences, on the contrary: they will be more motivated to pass them with all the bad consequences. Not long ago we thought people would not be crazy enough to go with their small children in wrecked boats. But they so, even in winter. Refugees deserve a safe haven but the people who live here deserve that we protect their welfare.

If the Turkey-Greek route closes, migrants will choose another way.

The flow will not disappear. Europe is a destination for life. For this we must be proud, but it has also disadvantages. Migrants will indeed try to find another way, however, this Turkish-Greek “highway”, which by now all of North-Africa has discovered, needs to be closed. Let us start with that. I don’t understand how we can put up with an illegal migration of this magnitude.”

Merkel Plan B – Der nötige Befreiungsschlag

Wenn der türkische Premierminister Ahmet Davutoglu diese Woche nach Berlin kommt geht es um viel: die Zukunft europäischer Asylpolitik, die Glaubwürdigkeit Deutschlands in der Flüchtlingskrise, und die Frage, ob Angela Merkel einen Plan hat, der funktionieren kann. Regierungschefs in Europa beschuldigen Merkel sie habe Hunderttausende „eingeladen“ und wisse nicht weiter. Ehemalige Verfassungsrichter und Bundeskanzler beklagen Planlosigkeit. Dabei hat Merkel einen Plan: er beruht auf der Erkenntnis, dass sich Kontrolle über Europas Außengrenze nur in Zusammenarbeit mit der Türkei zurückgewinnen lässt. Dafür muss die EU der Türkei etwas bieten: die geregelte Übernahme von Flüchtlingen, Finanzhilfen, Visumfreiheit. Dafür setzt sich Merkel seit Oktober ein.

Hat sie sich geirrt? Nichts deutet darauf hin, dass sich 2016 weniger Menschen über die Ägäis auf den Weg machen werden als im letzten Jahr. Oder dass weniger Kinder ertrinken werden. Dennoch ist die deutsche Kanzlerin ihren Kritikern voraus. Wer deren Alternativen durchdenkt, erkennt, wie wenig Substanz sie haben. Manche träumen von einem Zaun nach israelischem Vorbild an der deutsch-österreichischen Grenze; oder von Australien, wo Flüchtlinge, die über das Meer kommen, auf Inseln gebracht werden. Doch der israelische Zaun wird von Soldaten mit Schussbefehl bewacht; der Bau hatte Jahren gebraucht. Und die EU hat im Gegensatz zu Australien keine Nachbarn wie Nauru, wo sie Flüchtlinge absetzten könnte. Von rechtlichen, politischen, moralischen Fragen einmal abgesehen: wie das „Schließen“ der Grenzen Deutschlands praktisch aussehen solle sagen Merkels Kritiker nicht.

Denn Merkel hat grundsätzlich recht: wenn Europa die Kontrolle über seine Grenzen wiedergewinnen will, geht das nur mit Hilfe der Türkei. Doch ihre Kritiker haben auch recht, wenn sie an der derzeitigen Strategie zweifeln. So wie man sich in Brüssel die Zusammenarbeit mit Ankara vorgestellt hat wird sie nicht gelingen. Versprechen sind zu vage. Es fehlt an Vertrauen und an klaren Signalen.

Und auch an Realismus. Selbst wenn türkische Politiker etwa regelmäßig versprechen, die Ägäis für Migration schließen zu wollen, wird ihnen das nicht gelingen und es genügt auch nicht zu versichern, dass sie „sich bemühen“. Notwendig ist eine Zusammenarbeit zwischen Griechenland und der Türkei wie es sie noch nie zuvor gab. Die Türkei müsste sich bereit erklären, jeden Flüchtling, der die griechischen Inseln erreicht, zurückzunehmen. Dafür gibt es schon das griechisch-türkische Rücknahmeabkommen; es ist kein rechtliches, sondern ein politisches Problem. Denn es fehlen noch zwei Voraussetzungen: die Türkei müsste im Einklang mit dem griechischen Recht ein sicherer Drittstaat sein, und dafür ihr Flüchtlingsgesetz, das seit 2014 in Kraft ist, umsetzen und bereits gestellte Asylanträge im Land sofort bearbeiten. Und Griechenland müsste sich logistisch vorbereiten, um jeden, der etwa nach dem 31. Januar Lesbos und andere Inseln erreicht, in die Türkei zurückschicken zu können. Das wäre sinnvoller als Hotspots für die Verteilung von Flüchtlingen aus Griechenland in andere EU Staaten, denn letzteres würde an der Zahl der Ankommenden nichts ändern. Die Planung müsste heute beginnen. Dafür bräuchte Athen Hilfe und die erklärte Bereitschaft der Türkei. Dann ginge es um zählbare Ergebnisse: wie viele Asylverfahren werden in der Türkei abgewickelt? Wie viele Leute werden von Griechenland jeden Tag zurückgenommen? Die Umsetzung türkischer Zusagen könnte man täglich überprüfen.

Warum sollte die Türkei darauf eingehen? Hier kommt Deutschland ins Spiel. Es ist unvorstellbar, dass die Türkei in den nächsten Monaten jeden Flüchtling, der Griechenland erreicht, zurücknehmen wird ohne konkrete, substantielle und sofortige Hilfe. Es fehlt in Ankara an Vertrauen in die Zusagen der EU, und dafür gibt es gute Gründe. Von den drei

Milliarden Euro Hilfe für Flüchtlinge ist nichts zu sehen. Das Versprechen auf Visaliberalisierung ist unverbindlich. Der Plan, Kontingente von Flüchtlingen aus der Türkei aufzunehmen, ist derzeit so wenig glaubwürdig wie der blamabel scheiternde Plan 160,000 Flüchtlinge innerhalb der EU zu verteilen. Bei der Kontingentlösung versteckt sich Deutschland hinter der Europäischen Kommission, und diese hinter dem Flüchtlingskommissariat der UN. Man kann eine richtige Idee auch durch schlechte Planung ad absurdum führen.

Denn auch hier gilt: Versprechen genügen nicht. Wenn Deutschland will, dass die Türkei ab dem nächsten Monat Flüchtlinge zurücknehmen soll, dann muss Deutschland bereit sein in diesem Jahr hundertausende Syrer direkt aus der Türkei aufzunehmen. Das kann gelingen, wenn deutsche Behörden dies direkt mit den Behörden in Ankara planen. Dafür bedarf es weder der Europäischen Kommission noch der UN. Merkel könnte Davutoglu anbieten, in einem ersten Schritt bis April 100,000 anerkannte syrische Flüchtlinge direkt aus den türkischen Flüchtlingslagern aufzunehmen. Diese sind bereits erfasst, man kennt ihre Nationalität, es kämen Familien, nicht nur Männer, und man könnte die Fingerabdrücke mit europäischen Datenbanken abgleichen. Dann könnte die Türkei täglich zählen, wie viele Flüchtlinge ihr abgenommen werden. Es gibt auch keinen guten Grund, warum Deutschland oder Schweden ihren Anteil an den 3 Milliarden Hilfe nicht direkt über nationale Organisationen ausgeben sollen, ohne Umweg über Brüssel. Es geht darum Schulen und Kliniken für Flüchtlinge noch in diesem Jahr zu bauen, Lehrer zu bezahlen. Wo Vertrauen fehlt, wie heute zwischen Ankara und der EU, müssen konkrete Resultate dieses erst aufbauen.

Bedeutet dies, dass sich Deutschland damit von einer notwendigen Reform des europäischen Asylwesens abwendet? Nein, im Gegenteil. Eine solche Reform kann nur gelingen, wenn die akute Krise unter Kontrolle ist. Erst dann kann Berlin fordern, dass ab jetzt in jedem Jahr bis zu 100,000 Flüchtlinge, die die EU erreichen, verteilt werden, als Preis für Schengen und Ersatz für das Dublin-regime. Dies entspräche der Anzahl von Menschen, die vor 2014 im Durchschnitt jedes Jahr die EU Außengrenzen überwunden haben. Gelingt es Merkel aber nicht in den nächsten Wochen einen Plan zu entwickeln, der Ergebnisse zeigt, dann führt dies zum weiteren Erstarken jener Kräfte in der EU, die das Asylrecht überhaupt abschaffen wollen; jener die gegen Flüchtlinge, die EU, die Türkei, für Putin und gegen Muslime agitieren.

Deutschland, Europa und die Türkei brauchen einen Merkel Plan B. Darüber müssen Merkel und Davutoglu reden. Davon muss Berlin Ankara überzeugen.

INTERVIEW IN DIE ZEIT

»Erdoğan needs Germany«

October 15, 2015

The political scientist Gerald Knaus on working together with Turkey, border controls and Germany’s role in receiving refugees.

DIE ZEIT: Mr Knaus, while Germany finds itself confronted with one million refugees, you are calling for taking in another 500,000.

Gerald Knaus: This is not as absurd as it looks at first sight. After helpless politicians proposed many faulty solutions in the past few weeks, chancellor Merkel needs to present something credible and tangible.

ZEIT: The plan that Angela Merkel will bring to Ankara comes close to a proposal you made already weeks ago – and now it became EU foreign policy. What exactly did you propose?

Knaus: Greece declares Turkey a safe third country. Turkey commits to readmitting all refugees that reach Greek islands through the Aegean, from a point in time to be specified. In return, Germany commits to granting asylum to 500,000 Syrian refugees from Turkey in the next twelve months. In addition, the EU visa requirement for Turkish nationals will be waived next year.

ZEIT: Why should this reduce the number of refugees who want to come to Europe?

Knaus: This offer is only for refugees who are already registered in Turkey. Thus no new incentives for refugees to travel to Turkey would be created by this plan. Then refugee families – half of the Syrians in Turkey are children – would no longer need to make the dangerous trip across the sea and the Balkans. This would quickly reduce the number of boats heading towards the Greek coast. The result would be what Angela Merkel and Horst Seehofer both demand: control of the external borders and an orderly process – and German emergency relief for refugees in a real crisis situation.

ZEIT: But Turkey is currently reeling from a terrorist attack of which nobody knows who was behind it. Kurds and members of the opposition are brutally persecuted. How is one supposed to declare such a country a safe third country?

Knaus: You have to differentiate between a safe third country and a safe country of origin. For refugees Turkey is a safe third country – even if it is not necessarily a country of safe origin for its own citizens. Currently, these two things are often confused. Under the new Turkish asylum law, refugees can apply for asylum, are not persecuted in Turkey, and are also not deported to Syria. And that’s decisive for this proposal. Whether the EU should declare Turkey a safe country of origin as the EU Commission suggested, raises doubts indeed.

ZEIT: But is it wise to demonstrate to an autocrat like Erdoğan in the run up to the elections how much one is dependent on him?

Knaus: Even Erdoğan needs Germany. Turkey finds itself in the biggest security crisis since the end of the Cold War. Russia is waging war north of Turkey, in Ukraine. The Russian air force is bombing Turkish allies in Syria in an alliance with Assad and Iran, both adversaries of Turkey. And Turkey itself is at war with the »Islamic State« and the PKK. The economy is no longer growing as it was in the last decade, and taking care of two million Syrian refugees is not easy. The refugee issue plays hardly any role in the electoral campaign.

ZEIT: Part of your proposal is visa free travel for Turkish nationals to the EU – what effects would this have in practice?

Knaus: I do not believe in a mass exodus of Turks. In the past few years the trend went the other way; especially from Germany more Turks immigrated to Turkey than did immigrate to Germany. For the young generation in Turkey, Europe only has a real meaning if they can actually travel there. The only danger that I see is if the situation in Southeast Turkey would descend into a full blown war like in the 90s.

ZEIT: But in the current political climate it is completely unthinkable that the chancellor would speak about a number of 500,000 she actively wants to bring to Germany.

Knaus: I know that in the first moment this sounds counterproductive. But you can make it clear to people that without an agreement more refugees are to be expected. Even now there is talk of one million. And in talk shows superficial solutions like fighting root causes, solving the situation in Syria and Libya, or sharing the burden in the EU are being floated.

ZEIT: What about the magic formula “transit zones”?

Knaus: What the German federal minister of the interior proposes would indeed reduce the number of applicants from Balkan countries who are being rejected anyway – but this is not about them. Above all, it is about civil war refugees. Often people will say that the EU needs to better secure its borders, introduce stricter border controls and better equip refugee camps in the region. But none of these proposals will solve our most acute problem: How to reduce the number of refugees reaching the external borders of the EU. No Frontex mission, no European quota, no perfectly equipped refugee camp will stop the desperate from trying to flee to Europe. But if there’s an impression in the public debate that there’s no limit at all for the number of refugees, then soon the readiness to help will turn into fear. That’s why I believe that we need to move fast. Angela Merkel and her political allies in Europe need to show that they – and not the extreme right – have a real solution to offer.

ZEIT: Why should European solidarity suddenly work now if there was already a lack of it in past months?

Knaus: If hundreds of thousands of Syrian children grow up without schooling and without perspective, if we lose an entire generation, this will not be without consequence for European security. There’s a helplessness among the political elite in the entire EU, from Greece to Sweden, nobody has an idea what to do. And extreme right parties profit from this, while having no real solutions to offer either. In this situation Germany is the only country that has the political credibility and economic clout to take the initiative. If Germany can’t deal with the problem, nobody else will manage to do so. But if Germany takes the lead, countries like Austria, Italy, France and Sweden will follow.

ZEIT: Viktor Orban accuses Angela Merkel of moral imperialism. This argument also goes down well with many Germans.

Knaus: Orban is right if he calls the hitherto existing international refugee policy hypocritical. On paper there’s a generous right to asylum. But at the same time everything has been done to prevent refugees from claiming this asylum. In recent years, UNHCR resettled only 100,000 refugees worldwide per year to wealthy countries. That’s of course a ridiculously low figure. But Orban’s response to this is to by de facto get rid of the right to asylum altogether. He regards refugees as criminals, as enemies, and refers to Hungarian experiences with the Ottomans, as if they were an invading army. He also says that the refugee crisis is a good opportunity to overcome the “liberal age of human rights.” Le Pen in France, Strache in Austria and others join in into that chorus. In the general helplessness such slogans are becoming more and more appealing.

ZEIT: The right and the left claim that 60 million people are fleeing and that we are only talking about a fraction.

Knaus: That figure is totally misleading. The biggest part of all refugees worldwide stay within their home countries. Syria is the biggest disaster. One fourth of all refugees outside of their home country are Syrians. Most of them now live in Turkey, in Jordan, and in Lebanon. Only a few years ago the number of migrants who tried to enter the EU illegally was 72,000. So this is not about a massive migration of the planet’s poor to the rich North that has been going on for a long time and will never end. This is a specific emergency situation.

ZEIT: Why should erecting borders not work?

Knaus: Angela Merkel said that she has lived behind a fence long enough and she knows that fences won’t help. At first sight that’s a strange argument: The Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall worked very well and repelled refugees for decades. But for that you need a death strip and a firing order. And even that could not deter many desperate people to try nevertheless. Merkel made it clear that she will not build this kind of fence. You could militarise your borders and regard refugees as enemies. But then you would need to give up European asylum law as we know it.

Gerald Knaus is chairman of the European Stability Initiative, a think tank advocating unconventional solutions to European crises.

Interview by MARIAM LAU and MICHAEL THUMANN

NEW ESI DISCUSSION PAPER – SUMMARY

17 September 2015

The situation on the European Union’s external borders in the Eastern Mediterranean is out of control. In the first eight months of 2015, an estimated 433,000 migrants and refugees have reached the EU by sea, most of them – 310,000 – via Greece. The island of Lesbos alone, lying a scant 15 kilometres off the Turkish coast and with population of 86,000, received 114,000 people between January and August. And the numbers keep rising. The vast majority of people arriving in Greece during this period were Syrians (175,000). They are all likely to be given refugee status in the EU if they reach it; in 2014, the recognition rate of Syrian asylum applications was above 95 percent. But to claim asylum in the EU, they need to undertake a perilous journey by land and sea.

In the face of this massive movement of people – the largest in Europe since the end of the Second World War – there have been two diametrically opposed responses.

Germany has responded with open arms to the tide of Syrian refugees pouring into its train stations. At the beginning of the year, Germany anticipated some 300,000 asylum claims. By May, this prediction had been revised to 450,000. The German ministries of interior and social affairs are now making preparations for 800,000 this year. The German vice chancellor and Social Democrat Party leader has stated that Germany can cope with a half a million refugees a year for the coming years. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, has become the face of this generous asylum policy. She has been widely hailed for her moral leadership; but she has also been accused by other EU leaders of making the situation worse, by luring ever more refugees into the EU.

A radically opposed agenda has been pushed by Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime minister. In early 2015, Orban vowed that Hungary would not let any Muslim refugees enter, making this promise in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre in Paris. He repeated this pledge in May, when the EU discussed quotas for sharing the refugee burden among member states. He warned in a speech in July that Europe was facing “an existential crisis.” He blames the refugees themselves, whom he labels economic migrants, and EU migration policy for the current crisis. And he does not mince his words: quotas for refugees are “madness”; “people in Europe are full of fear because we see that the European leaders, among them the prime ministers, are not able to control the situation”; European leaders live in a dream world, failing to recognise that the very “survival of European values and nations” is at stake. Orban declared the issue a matter of national security, ordered a fence to be built, deployed the military, used teargas and passed legislation to criminalize irregular migration. He has also taken this message to the country at the core of the refugee debate, Germany, convinced that before long German public opinion will force Merkel and her allies around to his way of thinking.

In reality, neither the German nor the Hungarian approaches offer a solution to the ever-increasing numbers of Syrian refugees crossing into Greece and on through the Balkans. Neither a liberal asylum policy nor a wire fence will prevent people from drowning in the Aegean. Although they are diametrically opposed in their views of the Syrian refugee crisis, neither approach is sustainable. This is because it is not the EU but Turkey that determines what happens at Europe’s southeastern borders. Without the active support of the Turkish authorities, the EU has only two options – to welcome the refugees or try – futilely – to stop them.

ESI proposes an agreement between the EU and Turkey to restore control of the EU’s external border while simultaneously addressing the vast humanitarian crisis. Rather than waiting for 500,000 people to make their way to Germany, Berlin should commit to taking 500,000 Syrian refugees directly from Turkey in the coming twelve months. While this would be an extraordinary measure, it is a recognition that the Syrian crisis is genuinely unique, creating a humanitarian crisis on a scale not seen in Europe since the Second World War.

It is essential that these 500,000 asylum seekers are accepted from Turkey, before they take to boats to cross the Aegean. As a quid pro quo, it is also essential that Turkey agrees to take back all the refugees that reach Greece, from the moment the deal is signed. It is the combination of these measures that will cut the ground from under the feet of the people smugglers. If Syrian refugees have a safe and realistic option for claiming asylum in the EU in Turkey, and if they face certain return back to Turkey if they cross illegally, the incentive to risk their lives on the Aegean will disappear.

These two measures would restore the European Union’s control over its borders. It would provide much-needed relief and support to Syrian refugees. And by closing off a main illegal migration route into the EU, it would reduce the flood of people now trying to reach Turkey from as far away as Central Asia. This would help to manage the huge burden currently faced by Turkey.

This proposal would take Germany’s readiness to welcome hundreds of thousands of refugees and redirect it into an orderly process where refugees no longer have to take their lives into their hands in order to claim asylum. At the same time, it would stop the uncontrolled flood of people across Europe, something Orban’s fence can never do.

If this agreement could be put in place quickly, before the seas get even rougher and the cold season closes in on the Balkans, it could save untold lives.

What might work: a two-pronged strategy

We therefore propose the following two-pronged strategy for addressing the refugee crisis.

First, Germany should commit to taking 500,000 Syrians over the next 12 months, with asylum applications made in an orderly way made from Turkey. The German government is already anticipating and preparing for this number of arrivals. But instead of waiting for them to make the sea and land journey, with all its hazards, they should accept claims from Turkey and bring successful claimants to Germany by air. Of course, Germany cannot, and should not, bear the whole refugee burden. Germany’s offer must be matched by other European nations – ideally through a burden-sharing arrangement agreed at EU level. It may make sense for the EU itself to manage the asylum application process. But such agreements take time to achieve.

Second, from the date that the new asylum claims process is announced, any refugees reaching Lesbos, Samos, Kos or other Greek islands should be returned back to Turkey based on a new Turkey-EU agreement. Initially, there would be huge numbers of readmissions – tens of thousands – presenting a major logistical challenge. But once it is clear that (i) the route through Greece is closed, and (ii) there is a real and immediate prospect of gaining asylum from Turkey, the incentives for the vast majority of people to pay smugglers and risk their lives at sea would disappear. Within a few months, the numbers passing through Greece would fall dramatically.

There are many reasons why this two-pronged strategy is the most credible solution to the crisis. It would place a cap on the number of Syrian refugees accepted into Germany. While amounting to an extremely generous response, it would not be the open-ended commitment that Merkel’s critics fear. It would enable the German government to assure the public that the crisis is under control, helping to prevent public support from being eroded.

It would provide Merkel with a ready answer to Orban’s criticism. The asylum process, while generous and humane, would no longer be generating incentives for desperate people to risk their lives at sea. Hungary and other transit countries would be relieved of the security challenge – and the political pressure – created by the mass movement of refugees, taking the heat out of the debate. It would destroy the business model of the whole criminal underworld of human traffickers.

Finally, it would relieve Turkey of a major part of its refugee burden. Furthermore, with the route into Greece closed, Turkey would cease to be a magnet for migrants from as far away as Central Asia. This would relieve the pressure building up on Turkey’s eastern borders. With Europe finally making a genuine effort to share the burden with Turkey, it can legitimately ask for more cooperation on managing the remaining migration flows.

In the interim, the solution is in the hands of Germany and Turkey. And a quick solution is sorely needed, before the seas grow even rougher and the cold season closes in on hundreds of thousands of desperate refugees seeking a route across the Balkans.

Presentation of these ideas on Austrian public television: http://tvthek.orf.at/program/ZIB-2/1211/ZIB-2/10595483/Gespraech-mit-Tuerkei-Experten-Gerald-Knaus/10595689

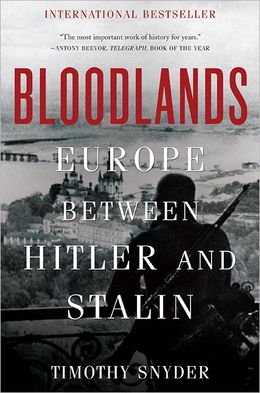

Looking to Kiev, as violent repression returns to the 20th century bloodlands of Europe (read Snyder’s excellent and haunting book, if you have not yet). It is heartbreaking.

It is also an urgent cause to reflect on one of the biggest policy opportunities by the European Union. Just as the experience of the Kosovo war in 1999 led a generation of European policy makers to reflect on the costs of disengagement in the Balkans, the experience of Kiev in 2014 should lead to a reflection on the costs of disengagement in Eastern Europe.

If one wants to find a date for when the EU lost the thread in this region I would suggest summer 2005.

2005 was one year after the big Central European enlargement. This remains the single biggest foreign policy success of any big power in the past 20 years. The EU – led by Germany – had done the right thing in 1997 when it decided to open accession talks with five, and in 1999 when it decided to open accession talks with another seven countries. This has remade the geopolitics of half of the continent. Germany under the Red-Green government, supported by France under Chirac and in alliance with the Prodi commission of the EU, had made this big enlargement their priority, (and a German close to the chancellor, Günter Verheugen, was put in charge of pushing it through) after 1999.

But then came the great disappointment. Following the 2004 enlargement, the EU – and Germany – failed to provide leadership, vision, and a strategy. Ukraine should have been offered a clear EU perspective after the Orange Revolution – and with it, serious EU involvement to help guide its transition and focus its reforms. This chance was missed.

The same offer should have been on the table in Vilnius in 2013 for Moldova and Ukraine. Another missed opportunity.

2005 was the turning point in this story. During the Ukrainian Orange revolution in early 2005 crowds in Kiev were waving European flags as they protested against election fraud. (Just as Ukrainian protestors in Kiev would wave European flags again after November 2013.)

The notion that continued EU enlargement was a good peace policy for the whole continent was still defended in Germany in early 2005, not only by the Red-Green coalition of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and his foreign minister Joschka Fischer, but also by Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats, then in opposition.

In January 2005 the opposition CDU in the German Bundestag called on the Red-Green government in power to offer the Western Balkans a more concrete accession perspective (Antrag der Abgeordneten und der Fraktion der CDU, Fuer ein staerkeres Engagement der Europaeischen Union auf dem westlichen Balkan, 25 Januar 2005). Signatories included, among others, Wolfgang Schaeuble, Ruprecht Polenz, and Angela Merkel.

Furthermore, in spring 2005 the CDU faction in the Bundestag, led by Angela Merkel, prepared a motion calling on the German government to also offer a concrete European perspective to Ukraine. Following the Dutch and French referenda in spring 2005, rejecting the EU Constitutional Treaty, this motion was silently buried and astonishingly never tabled!

In early 2005, there was still talk across the continent about the EU’s ability to attract and thereby transform the states around it. As Mark Leonard, a prominent think-tanker, argued in a book that appeared in 2005:

“The overblown rhetoric directed at the ‘American Empire’ misses the fact that the US reach – militarily and diplomatically – is shallow and narrow. The lonely superpower can bribe, bully, or impose its will almost anywhere in the world, but when its back is turned, its potency wanes. The strength of the EU, conversely, is broad and deep: once sucked into its sphere of influence, countries are changed forever.”

This was not based on wishful thinking, but rather on the real experience of the previous decade in Central Europe. Enlargement had helped overcome age-old suspicions. It had helped stabilise a young democracy. It had helped rebuild economies in turmoil following the collapse of communism. It also helped resolve bilateral conflicts for good. The experience of Germany and Poland was only one dramatic illustration of this promise in action. In 1990 the number of Poles who feared Germany still stood above 80 per cent. By 2009 it had fallen to 14 per cent.

In 1999 in Helsinki the EU gave candidate status to Turkey. In 2000 in Zagreb, and even more explicitly in 2003 in Thessaloniki, the EU held out the promise of accession to all of the Western Balkan states. Turkey received a date for the opening of accession talks in December 2004, and EU enlargement commissioner Gunther Verheugen confided to associates at the time that he expected Turkey to likely be a full member by 2014. Following the Rose Revolution in Georgia in 2004, the idea of offering a European perspective to the first South Caucasus republic did not appear far-fetched. European flags were put up outside all of the government buildings in Tbilisi.

This was all to change after summer 2005. First, the crisis over the EU’s constitutional treaty, followed by the onset of a global economic crisis in 2008, dramatically changed the policy discourse on enlargement in Europe. Almost as soon as Mark Leonard’s book praising the EU for its policy of transformation through enlargement – Why Europe will run the 21st century – was published, the book’s premise came into doubt. Inside, the EU policy makers questioned whether the Union had already over-expanded. This further undermined the EU’s self-confidence. Then came the Euro-crisis. There were concerns over populism in new member states – with the focus first on Poland, then Slovakia, and finally Hungary. The Euro-crisis after 2008 undermined the notion that EU enlargement actually changed countries “forever.” Concerns mounted over weak institutions and corruption in Romania and Bulgaria. There was intense frustration over administrative capacity in Greece, a long-time member state.

An air of fragility and doubt took hold. In light of multiple European crises, a different consensus emerged: enlargement, the EU’s flagship policy of the early 21st century, is not a solution to the problems of the continent, but rather a source of its problems. Enlargement had already gone too far. It could not continue as it had in the past. In 2005, following the French and Dutch referenda which rejected the EU constitutional treaty, Michael Emerson predicted that while accession treaties have been signed with Bulgaria and Romania, “ratification by the French parliament cannot be taken for granted. For other candidates or would-be candidates, the general message is ‘pause’.” [1]

And doubt was infectious. As the EU began to doubt its ambitions, its neighbors, from the Balkans to Turkey, from Ukraine to Georgia, began to doubt its commitment. They no longer took for granted that article 49 of the EU’s own treaty (!) really applies – which states that “any European State which respects the European values and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union.”

Doubt undermined trust, which has since translated into a sense of betrayal, most visibly in Turkey. Turkey has been negotiating with the EU since late 2005. With the Turkey-EU accession process in crisis, further enlargement as a strategy for peace-building and conflict prevention in Europe came to sound almost utopian. Former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer, a champion of EU enlargement when in office, has now wrote in a book on Europe 2030: “while almost all of the EU’s neighbors wish to join, its own citizens increasingly oppose not only further expansion but also deeper political integration.” Fischer concluded:

“I doubt that Europe’s malaise can be overcome before 2030… While the partial creation of a common defense system, along with a European army, is possible by 2030, a common foreign policy is not. Expansion of the EU to include the Balkan states, Turkey and Ukraine should also be ruled out.”

However, here is the catch: enlargement has found no successor as a strategy to overcome conflicts on the European continent. All attempts to find alternative foreign policy strategies to tackle conflicts have failed.

This is obvious from Ukraine to the Balkans to the South Caucasus. Tensions remain high everywhere once enlargement is put on hold and discarded. Take the Caucasus for instance. Recent years have seen a war (Georgia in 2008). There are continued casualties along the Armenian-Azerbaijani cease-fire line. The borders between the territory controlled by Georgia and the land controlled by Abkhaz and South Ossetian troops are tense. International diplomacy has resembled a string of failed initiatives by the US, Russia, Turkey, Germany or the EU whenever one of them made an effort to actually try to solve any of these seemingly intractable conflicts.

This failure to find alternative policies to avert regional conflicts is the conundrum facing European policy makers today. Neither Europe nor the US have shown any evidence that they can remake either Afghanistan or the Middle East. But in South East and Eastern Europe, all the tools exist to prevent a return to the tragedies of the 20th century. In this case, it really is a matter of will and vision. Or sadly, lack thereof, as we see now in Kiev.

In the Western Balkans the process of enlargement linked to conflict has produced the most impressive results for EU foreign policy anywhere in the world, post 1999. (This too might be put at risk unless enlargement retains its mobilising power for reforms).

In the South Caucasus the absence of even a vague promise of enlargement coincides with paralysis, frozen conflicts, closed borders, and rising regional mistrust.

As for Ukraine, the images from Kiev speak for themselves. Where just recently peaceful crowds were waving the European flag, snipers have moved in.

Enlargement has stabilized the continent like no other policy. There is still demand for it. And yet, for now, there is no supply.

And so today, ten years after 2004, there is a choice again between two courses of action in the face of failure.

One seems easier in the short term: to resign. To note that “the late 90s are over,” that enlargement has “not really worked” (as if the EU crises today had been caused by Bulgarian accession), that it cannot be defended in front of sceptical publics, that the EU lacks leaders.

The alternative option is to recognise and explain, again and again, what a nightmare of insecurity a small EU would face today. One in which Bulgaria, Romania, and certain Baltic countries would not have been admitted, and no promise would have been made to Serbia and other Balkan states in 2003 at the EU Thessaloniki summit.

It is to make a strong case to offer a membership perspective to Moldova and Georgia today – and expect them to meet the Copenhagen political criteria.

To maintain the pan-European instruments to defend democracy also in the East – ODIHR for election monitoring, the Council of Europe (today almost farcically useless in the East).

To take a serious look at the instruments the EU is currently using – in Turkey, in the Balkans – and sharpen them.

For the EU to use all available tools – visa bans, competition policy, support to independent media – to confront the Russian vision of “managed democracy” (which is just neo-autocracy).

To fight for release of all political prisoners. And to focus on the East not just when the streets are burning… and not only in Vilnius or Stockholm, but also in Madrid and Rome.

To defend the vision of “one Europe, whole and free.”

This is still the only credible alternative to a return to 20th century horrors. And the cheapest security and foreign policy there is for the EU.

PS: Anne Applebaum’s review of Bloodlands:

“This region was also the site of most of the politically motivated killing in Europe—killing that began not in 1939 with the invasion of Poland, but in 1933, with the famine in Ukraine. Between 1933 and 1945, fourteen million people died there, not in combat but because someone made a deliberate decision to murder them. These deaths took place in the bloodlands, and not accidentally so: “Hitler and Stalin rose to power in Berlin and Moscow,” writes Snyder, “but their visions of transformation concerned above all the lands between.”

[1] Michael Emerson , “The Black Sea as Epicentre of the Aftershocks of the EU’s Earthquake”, CEPS Policy Brief 79, July 2005, p. 3.

The Future of European Turkey

Gerald Knaus and Kerem Öktem

17 June 2013

On Saturday night, central Istanbul descended into apocalyptic scenes of unfettered violence. The police targeted tear gas, water cannons and plastic bullets at protestors, and stormed a hotel near the park, which had set up a makeshift clinic to treat children and adults caught up in the events. Among those trapped in the hotel was the co-chair of Germany’s Green Party, Claudia Roth, who is an avid follower of Turkey’s politics, a witness to the decade of violence in the 1990s in the country’s Kurdish provinces, and politician who supported the Turkish government’s democratic reform process. Shaken and affected by the teargas fired into the hotel lobby, she described her escape from Gezi Park, which she had visited in a show of solidarity. “We tried to flee and the police pursued us. It was like war”.[1] She added the next day that it is the peaceful protestors in Gezi Park and elsewhere, braving police violence to stand up for the democratic right to speak out, who are providing the strongest argument for advocates of the future European integration of Turkey.

Only a few hours before Roth’s initial statement on Saturday, the protestors in the Gezi Park and Taksim Square were discussing the results of a meeting of their representatives with the Prime Minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Erdoğan seemed to have made some concessions and accepted part of the requests of the protestors to reconsider the construction scheme on Taksim and wait for a pending court decision. The Taksim Platform, the closest there is to a representative body of the protestors, had decided to take down the different tents of trade unions and political organizations and only leave one symbolic tent. Most protestors were getting ready for a final weekend in the park, before returning to their lives as usual. True, the Prime Minister had delivered a warning for the park to be cleared, but such warnings had been made before and passed without decisive action. The mood among the people in the park was to wind down the protests and consider new ways of political mobilization. So hopeful was the spirit on Saturday that families took their children to the park to plant trees and flowers and get a sense of what has arguably been Turkey’s largest and most peaceful civil society movement ever. No one was expecting a major crackdown. They have been proven terribly wrong.

Should they have listened to Egemen Bağış, Turkey’s EU minister and chief negotiator? On Saturday, well before the evening raid, he not only scolded international news channels like CNN and BBC for having made a “big mistake” by reporting the protests live and accused them for having been financed by a lobby intent on “doing everything to disturb the calm in our country.” He also declared that “from now on the state will unfortunately have to consider everyone who remains there [i.e. the Gezi Park] a supporter or member of a terror organization”.[2] In the last three weeks of the Turkey protests, we have already witnessed the Prime Minister turning to a progressively belligerent rhetoric for reasons of his power-political calculus. Now it appears that the Minister responsible Turkey’s European future has not only been aware of the massive police brutality that was to be unleashed on the peaceful protestors, but also that he fully endorsed it. No European politician, no representative of any European institution will be able to meet Mr Bağış from now on, without taking into consideration his justification of the breakdown and his inciting rhetoric, which confuses citizens pursuing their rights to free assembly with terrorists.

Within only a few hours, the government of Prime Minister Erdoğan has destroyed all hopes for a peaceful resolution of the conflict, which is now spreading all over the country. Yet no friend of Turkey would want to see the country descending into violence. So what remains as a possible way out of ever deepening polarization?

In recent weeks some members of the Justice and Development Party have publicly expressed their dismay at the unfolding events and the polarizing rhetoric of Erdoğan. President Abdullah Gül has voiced concern too, but he has stopped short of condemning the police violence and criticizing the Prime Minister openly. Gül is a respected politician and enjoys considerable public sympathy. Many have praised the President’s conciliatory style of politics. The time has come for him to show his statesmanship and to speak out clearly and forcefully against the abuse of power, which the government of the Justice and Development Party has been engaging in in recent days.

The president should in particular oppose the witch hunt against protestors and against the doctors and lawyers who have supported them. Such action may yet avert the country’s deterioration into further violence and polarization. The president would also do a great service for those, Turkey’s citizens and many European friends alike, who continue to believe in a common European future.

Gerald Knaus, European Stability Initiative, Berlin/Paris/Istanbul

Kerem Öktem, St Antony’s College, University of Oxford

PS: See also the appeal, in German and Turkish, just published by director Fatih Akin:

„Sehr geehrter Herr Gül,

ich schreibe Ihnen, um Sie über die Ereignisse vom Samstagabend zu informieren, da die türkischen Medien kaum bis gar nicht darüber berichtet haben.

Samstagabend wurden in Istanbul erneut hunderte von Zivilisten durch Polizeigewalt verletzt. Ein 14jähriger Jugendlicher wurde von einer Tränengaspatrone am Kopf getroffen und hat Gehirnblutungen erlitten. Er ist nach einer Operation in ein künstliches Koma versetzt worden und schwebt in Lebensgefahr.

Freiwillige Ärzte, die verletzten Demonstranten helfen wollten, wurden wegen Terrorverdacht festgenommen. Provisorische Lazarette wurden mit Tränengas beschossen.

Anwälte, die gerufen wurden, festgenommene Demonstranten zu verteidigen, wurden ebenfalls festgenommen.

Die Polizei feuerte Tränengaspatronen in geschlossene Räume, in denen sich Kinder aufgehalten haben.

Die bedrohten und eingeschüchterten türkischen Nachrichtensender zeigten währenddessen belanglose Dokumentarfilme. Diejenigen, die versuchen über die Ereignisse zu berichten, werden mit hohen Geldstrafen und anderen Mitteln versucht, zum Schweigen zu bringen.

Eine Trauerfeier für Ethem Sarisülük, der bei den Demonstrationen ums Leben gekommen ist, wurde verboten!

Stattdessen darf ein Staatssekretär hervortreten und alle Demonstranten, die am Taksim Platz erschienen sind, als Terroristen bezeichnen.

Und Sie, verehrter Staatspräsident, Sie schweigen!

Vor zehn Jahren sind Sie und Ihre Partei mit dem Versprechen angetreten, sich für die Grund- und Bürgerrechte eines jeden in der Türkei einzusetzen.

Ich möchte nicht glauben, dass Sie sich um der Macht wegen von Ihrem Gewissen verabschiedet haben. Ich appelliere an Ihr Gewissen: Stoppen Sie diesen Irrsinn!

Fatih Akin

Die türkische Version des offenen Briefes:Sayın Cumhurbaskanım,

Belki duymamissinizdir diye dusunerek yaziyorum.

Dun aksam saatlerinde yeniden baslayan polis siddeti sonucunda yuzlerce insan yaralanmıstir.

14 yasinda bir cocuk, polisin attigi biber gazi mermisiyle beyin kanamasi gecirdi. Ameliyatin ardindan simdi uyutuluyor. Hayati tehlikesi yuksek.

Yaralilara yardim etmek isteyen gonullu doktorlar, terorist diye gozaltina alınıyor. Revirlere gaz bombalarıyla saldırılıyor.

Gozaltina alinanlarin haklarini savunmak isteyen avukatlar gozaltina alınıyor.

Polis, kapali alanlarda gaz bombası kullaniyor. Bu yetmezmis gibi, insanlarin kendilerini korumak için taktigi basit gaz maskelerini cikarttiriyor. Sularina el koyuyor.

Tehdit ve gozdagiyla susturulan medya, belgesel yayinlamaya devam ediyor.

Gercekleri gostermeye calisanlar agir para cezalari ve baskilarla susturulmaya calisiliyor.

Milletvekilleri de polis siddetinden payina duseni aliyor.

Gosterileder polis kursunuyla oldurulen Ethem’in cenaze torenine bile izin verilmiyor.

Bir bakan cikip, Taksim Meydanda olan herkesi terorist ilan edebiliyor.

Polis hicbir ayirim gozetmeden halka tonlarca biber gazi, gazli su, plastik mermiyle mudahale etmeye devam ediyor.

Ve siz, susuyorsunuz..

Cok degil, on yil once, temel hak ve ozgurlukleriniz icin mucadele eden siz ve sizin partiniz… Bu halki en iyi sizin anlamaniz gerekmez mi?

Iktidar gomlegini giyen digerleri gibi vicdanınızı soyunup bir tarafa biraktiginizi dusunmek istemiyorum.

Vicdani olanlara sesleniyorum; bu vahseti durdurun!

Fatih Akin

Leader of the German Green Party Claudia Roth, attacked by tear gas

Her interview on what this means for Turkey-EU relations is here (in German)