On 5th October I was invited to the anniversary conference commemorating the overthrow of Slobodan Milosevic in Serbia one decade ago. It was a thought-provoking gathering with a wide range of speakers: Serbian president Boris Tadic, Bozidar Djelic, Mikulas Dzurinda, Vuk Jeremic, Eduard Kukan, George Papandreou, Francois Heissbourg, Goran Svilanovic, Pavol Demes and others.

I also gave a presentation, a short version of arguments my colleagues and I are developing fully for a forth-coming ESI paper on the Balkans – any feedback at this stage is very welcome!

Belgrade, 5th October 2010

Dear friends,

It is a great privilege and pleasure for me to come to Belgrade on this special occasion, to look back at an eventful decade with so many friends, to take stock, to take heart, and to share ideas about the lessons the recent past holds for all of us, interested in democratisation in general and in South East Europe in particular.

At the same time this event is more than a celebration of the breakthrough in October 2000. It finds many of us impatient; it is not merely, or even mainly, an occasion to rejoice in what has been achieved, but more importantly a chance to assess what still needs to be done. In recent months we have all come across symptoms of “Balkan fatigue” in many quarters, a sense of frustration that things are not moving along faster.

So let me take a closer look today at some causes behind the impatience many of us feel; at some specific challenges the Balkan region faces in realising the vision of a “return to Europe” that president Tadic outlined at the opening of today’s event; and in particular at the role, policies and responsibilities of the European Union.

Battle of ideas

There are different ways to convey how far the region, and Europe as a whole, has come since the 1990s. One is to focus on the battle of ideas. So here are two prominent European thinkers looking at the Balkans in the first half of the 1990s. One is French philosopher Jean Baudrillard. In 1994 he published an article in the Belgrade paper Borba, under the titel “Without Pity”. There he argued, against the background of the war in Bosnia, that “all European countries are going the way of ethnic cleansing. That is the real Europe … Bosnia is only its new frontier.” Two years earlier an Irish writer, Conor Cruise o’Brien, had offered an equally glommy take on the Balkans. He wrote in 1992:

“There are places where a lot of men prefer war, and the looting and raping and domineering that go with it, to any sort of peace time occupation. One such place is Afghanistan. Another is Yugoslavia …”

These deeply pessimistic visions, arguing either that the whole edifice of post-World War II European civilisation was brittle, and all of Europe was doomer to a “normality” of clashes of civilisation and ethnic hatred OR that, at the very least, Balkan people and societies belonged to a different, pre-modern world distinct from the “civilised” rest of Europe, were actually widely shared in the 1990s … not only in Belgrade or Zagreb, but also in Paris, London, Athens and elsewhere in the EU. This also explains how it was possible for a UN general, Canadian Major General Louis MacKenzie, head of the UN peacekeepers in Bosnia, to tell the US congress in May 1993 that the law of the jungle was the true law of humanity: “Force has been rewarded since the first caveman picked up a club, occupied his neighbour’s cave, and ran off with his wife.” This explains how it was possible for Karadzic and Mladic to be welcomed as heros in Athens in the early 1990s. It explains why some leaders thought that the most “realistic” response to the Balkan tragedy was to let events run its “natural” course. If soft power is the ability to get others to want what you want, then European soft power in the 1990s suffered from the obvious: that it was not clear what Europe wanted.

Ideas matter. Nationalist ideas. Ideas of Balkan exceptionalism. Erik Hobsbawm has underlined that intellectuals are to national movements what”poppy growers in Pakistan are to heroin addicts – the suppliers of the raw material for the market.” There were many such poppy growers, mainly but not only, in the Balkans. They prepared the ground, first for the disastrous wars of the 90s, then for the failures to stop them.

At the same time during the 1990s the notion of a “return to Europe” was a complex one. There was a time, not long ago, when “Europe” did not stand for values of democratic governance and peaceful interdependence: when, as historian Mark Mazower reminds us in Dark Continent, European civilisation was not actually tending towards democracy. Mazower writes that “though we may like to think democracy’s victory in the cold war proves its deep roots in Europe’s soil, history tells us otherwise. Triumphant in 1918, it was virtually extinct twenty years on.” There is a strong non-democratic, nationalist, militaristic and authoritarian 20th century European tradition, and it is one that Balkan leaders such as Slobodan Milosevic could refer to when they stressed the supposed debt Europe owed to Serbia. As he put it in his infamous 1989 speech in Kosovo Polje, he too was in favour of a “return to Europe”:

“Six centuries ago, here on Kosovo field, Serbia defended herself. But she defended also Europe. She stood then on the rampart of Europe, defending European culture, religion, European society as a whole. That is why today it seems no only unjustified, but also unhistorical and completely absurd to question Serbia’s belonging to Europe.”

Of course, after world war II Western Europe embraced other values. The question in the 1990s was in which European tradition Serbia and other Balkan countries saw themselves: the first or the second half of the 20th century. The Central Europeans made a clear choice in 1989. The results were dramatic. In 1990 the number of Poles who feared Germany was above 80 percent. By 2009 it had fallen to 14 percent. After 1989 the goal of joining an integrating democratic continent spread across the whole of Central Europe. And in October 2000, on the day we remember today, it finally became realistic to imagine that the same ideas would be embraced across the whole of the Western Balkans as well. It was also a major breakthrough in the battle of ideas.

October 2000 was followed by the EU Balkan Zagreb summit in 2000. There and then the EU stated that it “reaffirms the European perspective of the countries” of the Western Balkans. This was an interesting way of bracketing the disastrous 1990s, in which few people – in the region and in the EU – had spent much time to think about this vision. This was in turn re-reaffirmed in the Thessaloniki Agenda for the Western Balkans in 2003 when the European Council “reiterated that the future of the Western Balkans is within the European Union”. Then the 2006 EU Salzburg Declaration noted: “the EU confirms that the future of the Western Balkans lies in the European Union.” Affirmed, reaffirmed, confirmed … the story of EU-Balkan relations in the decade since 2000 is the story of an increasingly dominant narrative, in which, officially, the future of the whole region is clear and settled. There would only be one Europe, and the Balkans were destined to be part of it.

The advantage of this kind of vision is that it leaves little space for alternative, and often dangerous, ideas. To be able to predict the future of a whole region reduces uncertainty and fear. French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner and Sweden’s Carl Bildt wrote in Le Figaro in 2008, for instance, that: “it is certain that Serbia will soon be a member of the EU, because there is no alternative. This is in tune with the march of history.” Lady Ashton, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, told civil society representatives in Belgrade in February this year that “the EU is determined that the future of the whole region lies in eventual accession to the EU.”

Malaise

So far, so good. However, if the direction of the “march of history” is clear, why is there such a feeling of unease across the whole region today? Is it really only because leaders in the region are not doing enough to reform their countries, which is a herculean task that will take more time? Or are there deeper reasons for concern?

In a recent book on Europe 2030, former German foreign minister Joschka Fischer, a big supporter of enlargement when in office, presented his personal view that the future of enlargement is grim: “while almost all of the EU’s neighbours wish to join, its own citizens increasingly oppose not only further expansion but also deeper political integration.” Fischer sees no happy end soon: instead, the spectre is of a Balkan accession process which will never end. He concludes:

“I doubt that Europe’s malaise can be overcome before 2030 … While the partial creation of a common defense system, along with a European army, is possible by 2030, a common foreign policy is not. Expansion of the EU to include the Balkan states, Turkey and Ukraine should also be ruled out.”

Fischer’s expectations echo and reflect the general debate in political circles in Berlin. We all remember the statement in the CDU election programme of 2009, which called for a “enlargement pause”:

“The enlargement of the EU from 15 to 27 members within a few years … has required great efforts. As a result the CDU prefers a phase of consolidation, during which a consolidation of the European Union’s values and institutions should take priority over further EU enlargement. The only exception to the rule can be for Croatia.”

Unfortunately, even at the time these were not just words: in March 2009 Germany – backed by Belgium and the Netherlands – blocked forwarding the application of Montenegro to the European Commission for an opinion. This had in the past been a mere technical step. And this, once established as a precedent, has now been repeated in the case of Serbia. Signals from Berlin today are that this could be overcome soon … but what to expect from the next government in The Hague, now dependend on the a good will of a politician, Geert Wilders, who told Euronews in 2009 that “no other country should join Europe. I’m even in favour of Romania and Bulgaria to leave [sic] the EU” ?

In the 1990s, in the streets of Belgrade in 2000, it was clear what supporters of a European democratic Balkans had to struggle against. Today the alternative ideologies inspired by early 20th century Europe have largely been defeated; the region has dramatically demobilised, cutting defense spending and ending conscription; key political actors everywhere have embraced the rhetoric of a European future for the Balkans. So has the EU, its leaders repeating the mantra at every gathering for a decade.

And yet, enormous uncertainties persists. As a very senior European official working on the Balkans told me just a few weeks ago:

“I do not know if the EU perspective is 10 or 100 years. I am selling 10, but in my heart of hearts I do not know if it is not in fact 100.”

If this is what people in the EU, working on the region, feel, one cannot blame people in the Balkans for wondering how certain their European future really is. This is the current EU-Balkan problem in a nutshell: few question the “perspective”. And nobody knows if it will be realised by 2020, 2030 or 2050.

The problem of the next step

Let us break down the problem to make it more manageable. To simplify, one could say that we have today an immediate “problem of the next step”: now that all the countries in the region (who are able to) have submitted their official applications for EU accession, the ball is in the EU’s court. But finding a coherent response is proving hard. Let me look at four specific problems in turn.

Bosnia-Herzegovina:

One can speak for days about Bosnia and its problems, which are as complex as its recent history; ESI has written many reports expressing our views, from the influence of a continuing (and increasingly discredited) international protectorate to the most promising way to advance a constitutional reform debate that makes Bosnia more functional. But there is one obvious reason why EU soft power is still so ineffective in Bosnia.

To have an EU perspective a country needs to find a consensus to apply and to meet the conditions to become a candidate. Yet the formal obstacle is obvious: as enlargement commissioner Olli Rehn stated clearly less than a year ago:

“Let me put it as plainly as I can: there is no way a quasi-protectorate can join the EU. Nor will an EU membership application be considered so long as the OHR is around. Let me even repeat this, to avoid any misunderstandings: a country with a High Representative can not become a candidate country with the EU.”

Olli Rehn is no longer enlargement commissioner, but Carl Bildt, who remains Swedish foreign minister, made the very same point in October 2009, “As you know the European Union is a union of sovereign democracies, not of protectorates. So, the presence of the OHR is, of course, blocking both the EU accession process and the NATO access process.”

This is not an isolated opinion at all. On 30 June 2010 the Communiqué of the Peace Implementation Steering Board repeated for the umpteenth time that this is remains the position of the PIC as well: http://www.ohr.int/dwnld/dwnld.html?content_id=45102

“The EU Member States of the PIC Steering Board reiterated that the EU would not be in a position to consider an application for membership by BiH until the transition of the OHR to a reinforced EU presence has been decided.”

This position also makes eminent sense: a country that is, supposedly, too fragile to cope without an international overlord, that is allegedly about to collapse if there is not always the option of a decree imposed from the OHR’s White House, is not meeting the minimum standards of being a stable democracy.

Behind the notion that Bosnia cannot cope without international protectorate institutions, however, stand a number of highly damaging attitudes towards Bosnia in general. Look, for a clear illustration, to the latest controversy over visa free travel for Bosnian citizens. As French state secretary for Europe Pierre Lellouche put it on 29 September, explaining why France at first suggested to postpone this step once more:

“La position du Gouvernement est la suivante : les visas relèvent de la sécurité et doivent donc s’accompagner de garanties très sérieuses. Or vous connaissez l?état politique de la Bosnie. Et pour qu’il y ait visa, il faut un État.”

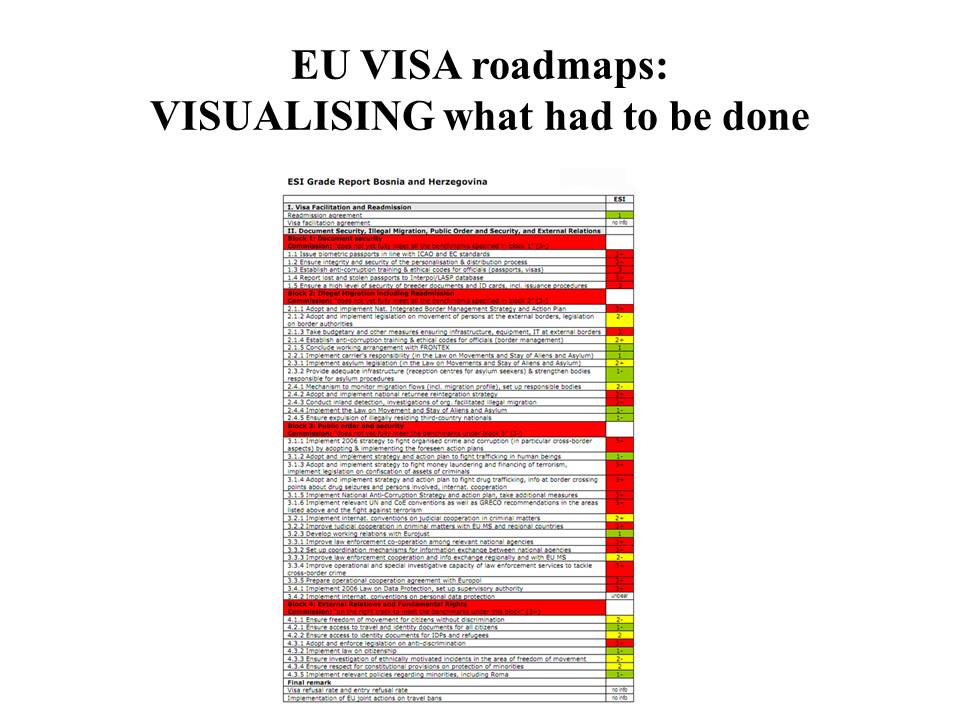

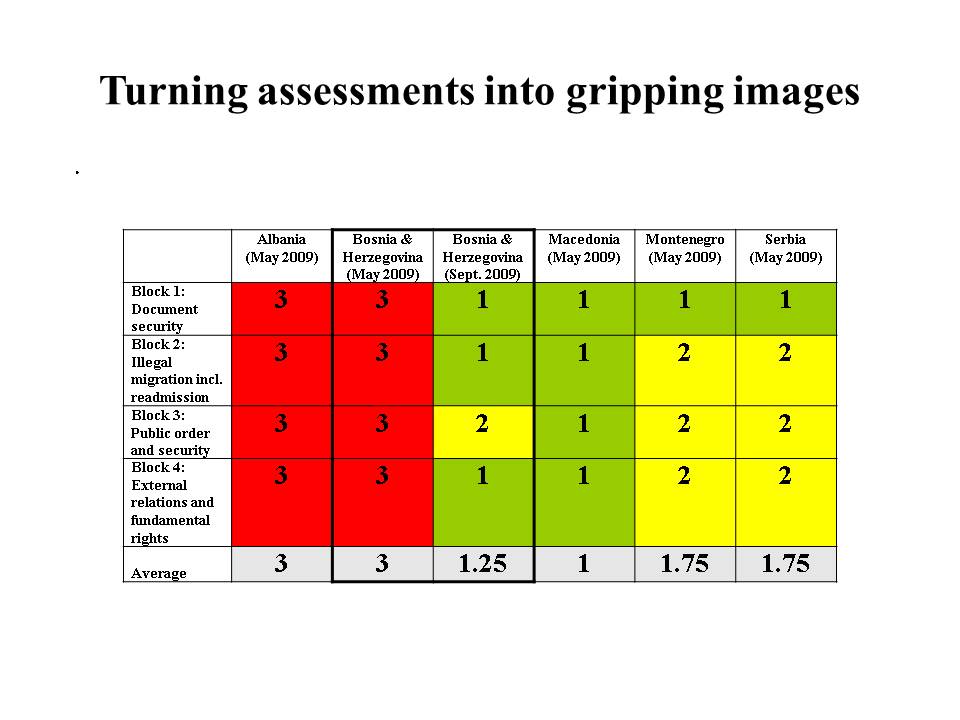

What makes this position – “for there to be visa there needs to be a state” both ironic and tragic is that this senior European politician willfully overlooks the fact that in this specific and demanding case Bosnian leaders and institutions WERE able to meet all the EU conditions.

Bosnia has carried out complex and demanding reforms, passes laws and reformed institutions – and ESI has looked into this in great detail, as have the EU experts and the Commission. However, this story does not fit into the narrative of a political class unable for a variety of reasons to respond to normal incentives.

To paraphrase Lellouche, in order to meet the visa roadmap conditions Bosnia DID have to show that it was capable of acting as a state. And indeed it did. But the real lesson is ignored: that when the EU treats Bosnia like a normal state, “strict but fair”, it also gets results.

Bosnia politics is indeed complicated, and will always be complicated; that is the fate of complex multiethnic democracies, from Belgium to Spain. At the same time, no other country in the region needs the EU pre-accession process more badly than Bosnia. To provide a clear anchor for reforms. To provide specific roadmaps. To translate a shared vision of the future into concrete tasks. This makes it all the more tragic that Bosnia is also trapped by exaggerated defeatism, which prevents outsiders from offering credible incentives.

Kosovo:

Here I can be even shorter, given the constraints of time and space. Kosovo does not at this moment have a European perspective, because, for the EU 27, it is still not a state. At the same time Kosovo does not have a credible Europeanisation process either. In legal terms and in the way its political debates develop, independent Kosovo is still a protectorate.

How long will the ICO remain the supreme legal and executive authority in Kosovo? It is unclear. How long will EULEX have an exectutive mandate? It is unclear. How long will EU member states disagree on Kosovo? For the foreseeable future.

Under these conditions Kosovo has no European perspective. This also means, however, that the EU also has very little and indeed diminishing leverage in Pristina. It is common in European capitals to blame Kosovo’s love for all things American on an irrational infatuation of the elites in Kosovo with the large power that brought about independence. However, the limited leverage of the EU is above all a reflection of the lack of any clear pre-accession process.

Unless the EU finds a way to develop a status-neutral Europeanisation process. Some in the Commission are trying to work on this, but without political commitment they will not get far.

Macedonia:

Macedonia was awarded candidate status in 2005. Four years later Macedonia received a positive assessment by the European Commission.

“The country fulfils the commitments under the Stabilisation and Association Agreement, has consolidated the functioning of its democracy and ensured the stability of institutions guaranteeing the rule of law and respect of fundamental rights and the country has substantially addressed the key priorities of the accession partnership”.

In 2009 also Macedonia signed and ratified the border demarcation agreement with Kosovo, thus solving a decade-long bilateral problem.

Finally, in October 2009 the Commission recommended Macedonia’s transition to the second stage:

“In the light of the above considerations and taking into account the European Council conclusions of December 2005 and December 2006, the Commission recommends that negotiations for accession to the European Union should be opened with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”.

At the EU Council in December 2009 the matter was postponed:

“The Council notes that the Commission recommends the opening of accession negotiations with the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and will return to the matter during the next presidency.” …

However, at the same time the Council asserted:

“maintaining good neighbourly relations, including a negotiated and mutually acceptable solution on the name issue … remains essential.”

This did not happen. So the Council did not return to the “Macedonian matter’ during the next (Spanish) presidency. For now, and unless and until this is resolved, Macedonia is as trapped as Kosovo and Bosnia.

Serbia:

Serbia, of course, is facing its own problems. What is problematic is never the reality of EU conditionality: this is, on the contrary, a positive tool to promote reforms and modernisation, as the President put it earlier today. The problem is that it is not always clear what exactly the conditions are.

One problem is expectations regarding Kosovo. Since the EU itself is divided over Kosovo, it is not always clear what it wants Serbia to do.

As the Belgian ambassador to Serbia noted recently Belgrade “must improve its relations with Kosovo” if it wants to join the EU and to “find a lasting modus vivendi”. French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner noted that “The independence of Kosovo is irreversible. The opinion of the ICJ signals an important step towards putting an end to the legal debate on this issue, which will enable all parties to devote themselves, from now on, to other pending issues.” And he went on: “Kosovo and Serbia must now also find the path of political dialogue in order to overcome, by adopting a pragmatic approach, the concrete problems that remain between Belgrade and Pristina, in the interest of everyone and, above all, the Serbian community of Kosovo.” As Beta news agency noted a few weeks ago “EU circles and the member states who have recognized Kosovo are increasing pressure on Belgrade over Kosovo”:

“Last week, top officials of Belgium, which currently holds the EU rotating presidency, made it clear to President Boris Tadic that granting Serbis the status of candidate country would depend on Belgrade’s moves concerning Kosovo … Now, the stand that Kosovo and Serbia’s accession to the EU are two separate processes is no longer mentioned in European Union circles.”

Indeed. But what does this mean in practical terms? The EU places a lot of trust in a dialogue, as Kouchner also explained:

“Such a dialogue is important for the stability of the region. It is also necessary because the two States, Serbia and Kosovo, intend to become Member States of the European Union, and because their accession will be based on the assumption that they have established normal inter-State relations with each other enabling them to work together towards European integration.”

When expectations are clear, as we have seen recently in the context of the UN debate, Serbia has in fact responded very constructively. But this needs to become the model: expectations and red lines need to be defined by the EU, based on a principled approach which envisages the whole region as future members of the EU. It often is not.

Then, however, Serbia complied and the focus of conditionality has shifted to ICTY. Again, there is a consensus in the EU on the need for Serbia to cooperate and for Ratko Mladic to end up in The Hague. However, it would be fatal if the impression gains ground, in Serbia and in the region, that general enlargement skepticism is hiding behind the argument that Serbia is not performing on this sensitive matter even if there might be evidence to the contrary. This would only help those in Serbia who do have an interest to torpedo its European perspective.

At this stage, the EU would do well to allow the technical process of integration – including the writing of an opinion on Serbia’s application – to go ahead. This must not mean abandoning the focus on ICTY, but it could mean applying a similar standard as the one which was applied to Croatia in its own accession process.

What is to be done?

In short, there is a clear need for fresh thinking. The bull needs to be taken by the horns: issues which have been left ambiguous need to be addressed.

It would be tragic if, having come so far, the EU accession of the Western Balkans now gets stuck at this stage. This calls for a proactive EU policy.

In Bosnia, the EU should move to bring the protectorate to an end, and to treat Bosnia fairly, like all other Balkan countries.

In Kosovo the EU needs – in its own, the Kosovo and even Serbia’s interest – define a way for Europeanisation and European leverage to work. This requires a credible European perspective, if need be a status-neutral accession process, as a recent ECFR paper has argued.

In Macedonia it is high time to find a creative solution – ESI has proposed one possible way forward recently, to link the entering into force of a new agreed name to the date of the countries’ actual EU accession.

And when it comes to Serbia the EU should be both “strict” and “fair”: conditionality must be transparent, based on clear principles and standards, not non-transparent and a moving target. This applies to expectations regarding Bosnia, Kosovo as well as ICTY.

Serbia, the EU and the whole region have come a long way since October 2000. But the journey is far from over, and it is not only the countries of the region which need to take a hard look at what would need to be done to ensure that in the end the destination of a Europe whole and free, integrated and including the Balkans, will be reached.