F.D.P. politician Joachim Stamp on his new post as special representative for migration agreements, the deportation of foreigners who commit crimes and the idea of transferring asylum procedures abroad.

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

This interview was first published in German by Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung on 4 February 2023:

“Manche Jungs glauben, dass sie bei uns fürs Fußballspielen bezahlt werden“

Excerpts from the interview:

Mr. Stamp, you have just taken office as the German government’s “special representative for migration agreements.” A tabloid called you “Germany’s top deportation commissioner.” Is that how you see yourself?

It’s explicitly not just about deportations, especially since the federal states are still responsible for that. It’s about a fundamentally new political approach: comprehensive agreements with the countries of origin, so-called migration agreements.

These agreements provide for a country to be granted a quota of legal immigration if it accepts back its own citizens who have committed criminal offenses in Germany or whose asylum applications have been rejected.

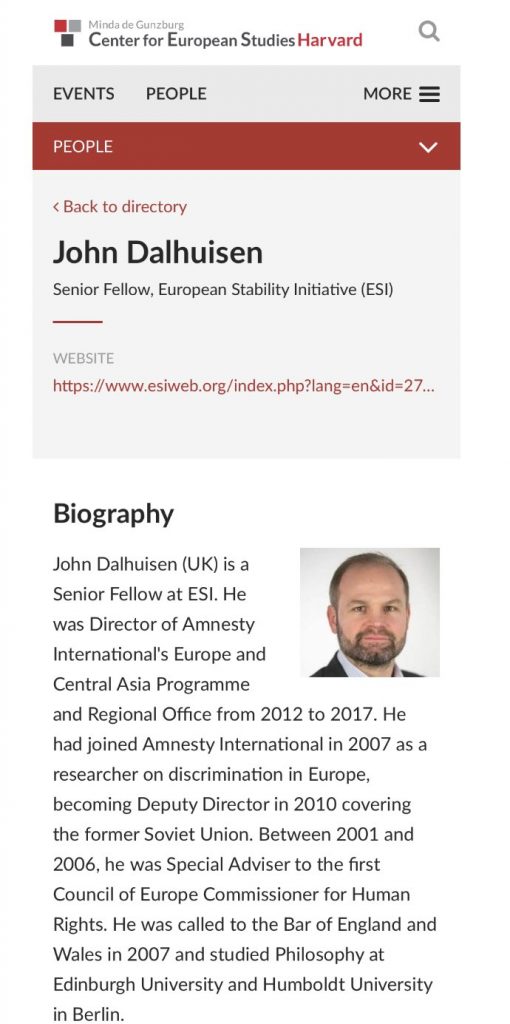

Such agreements would have to vary from country to country. But in principle, we agreed in the coalition agreement between the two parties to reduce irregular migration and strengthen regular migration. The idea goes back to proposals such as those made by migration researcher Gerald Knaus, with whom I am in regular contact.

In 2019, Knaus proposed concluding an agreement with The Gambia as a model: Legal immigration within a certain quota, if Gambia first takes back criminals as well as, from a cut-off date, all other nationals who come to Germany outside this quota.

This is actually a model that is very conceivable.

…

But the coalition agreement also says: “Not every person who comes to us can stay. We are launching a repatriation offensive to implement departures more consistently, especially the deportation of criminals and dangerous persons.” How is this to be achieved?

In the past, there were always steep announcements about deportations from certain politicians, but experience shows that nothing happens without the willingness of the countries of origin to take back their citizens who are obliged to leave the country. Some countries of origin also refuse to take back their citizens because a strong diaspora in Germany is economically important to them through remittances. Such transfer payments are often much higher than German development aid, which is why threatening to cancel them makes little impression. We have to convey to these countries that it is better for them if their people do not live here in illegality but in a regular way, because then they are of course much stronger financially and can better support their home country. For this, we can offer a certain number of regular visas to study here, to do an apprenticeship or to go directly into the labour market. Through the newly created right of opportunity to stay, we also offer those who are already here and who have a job here a prospect of legalizing their status. But we also have a clear expectation: in order to provide the integrated majority with a regular status, countries must take back their citizens who are considered criminals and dangerous persons here – and, from a certain date, all other of their citizens who still come to Germany irregularly.

The 2016 agreement between the EU and Turkey was based on a similar model. However, it has failed.

Initially, the agreement helped to greatly reduce migration flows on the Balkan route. This was also because Turkey was given the means to integrate millions of refugees from Syria, who then did not even make their way to Europe. The fact that this later developed differently due to the policies of Turkish President Erdoğan is another matter.

Some EU states have other ideas for controlling the so-called Balkan route than migration agreements. Vienna, Budapest or Athens, for example, are calling for EU funds to further expand Greece’s and Bulgaria’s border fences with Turkey.

I am sceptical about this. Of course, Europe’s external borders must be protected. But barbed wire and fences alone are not enough to stop irregular migration. Instead, agreements with the countries of origin can ensure that people don’t venture into the desert in the first place, don’t board unseaworthy boats in the Mediterranean, and don’t climb over barbed-wire fences only to end up here in an asylum system where they don’t belong because they are not persecuted in their countries. We want to create opportunities for a limited and contingent number to apply regularly for the German labour market, provided that those who try to do so on their own and who have no right of asylum here are readmitted by their countries of origin without further ado. We have had good experience with the Western Balkans arrangement. While the circumstances are somewhat different in this case, we want to extend the principle similarly to other countries and regions of the world. Of course, there are countries with which we cannot reach agreements at present for fundamental reasons, such as Syria or Afghanistan. But we will seek dialog with many other countries.

…

Your title “Special Representative of the Federal Government” sounds solemn, but you are a king without a country, since you have no real powers. Who are your most important partners?

That remains to be seen. We have excellent civil servants in the ministries, but there has been a lack of a body to bundle the initiatives of the various ministries into a strategy. That is also my task. If, for example, the Ministry of Labor wants to recruit workers in a particular country, this should be coordinated not only with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Development, but also with the Ministry of the Interior in such a way that the obligation to leave the country for people without the right of residence is also integrated into the agreements from the outset. We also need to bring practitioners together, even beyond the usual hierarchies. In my years as Integration Minister in North Rhine-Westphalia, I often experienced criticism from the federal police to the municipalities and from the municipalities to the federal police because there was a lack of agreements. There continue to be errors and gaps in logistics that repeatedly lead to delays or cancellations of deportations. Practitioners from all agencies involved can certainly achieve many improvements by talking directly with each other.

…

Many companies that have found workers abroad and can present signed employment contracts complain that this is not the case.

This has been a problem for a long time. In my time as minister, companies complained about this time and again. We need to make greater use of digitization here, and we also need to increase the number of staff in the relevant departments. We also need to become more flexible in the recognition of educational and vocational qualifications if we want to manage labor immigration well. However, I would caution against exaggerated expectations. None of this will bring quick results overnight. What is important is that we start down this new path and network the work between the ministries more closely.

According to the coalition agreement, the traffic lights also want to examine whether asylum procedures can be relocated to third countries. What does that mean exactly?

That we want to examine whether asylum procedures can be carried out in third countries, for example under the umbrella of the UNHCR, in compliance with the Geneva Refugee Convention and the European Convention on Human Rights. Then people rescued on the Mediterranean would be brought to North Africa for their proceedings. But that requires a great deal of diplomacy and a long lead time. And it is clear that a country like Libya, for example, cannot be a partner for this in its current state. We need to take a close look at developments in potential partner countries. We are not talking about a quick fix, as former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson did with Rwanda.

Whereas British courts have ruled that Johnson’s move to transfer British asylum procedures to Rwanda is compatible with the UN Refugee Convention.

It is important that the standards of international law are upheld; anything less is out of the question. But on this basis, we actually want to think about it.

You will certainly get applause for this from parts of your party – but will the Greens go along with it?

It is crucial that we both end the deaths in the Mediterranean and the pushbacks at the EU’s external borders and reduce irregular migration. To do this, we need to remove the motivation for people to embark on the life-threatening crossing in the first place. This can be accomplished by providing regular alternatives to entry for a select group, if all others without asylum rights are consistently deported. Another case is those who entered irregularly, but who have abided by all the rules here for years. People who are integrated into the labour market and learn the language, whose children go to school, who have become a natural part of our society. We want to make it possible for them to stay permanently. On the other hand, we want to put all our concentration into getting rid of those who don’t play by the rules.