Later this week – on Friday at 3 pm in Haus der Musik in Vienna – ESI and Erste Stiftung will organise a public debate on lessons from internationnal interventions.

One of the panelists, Minna Jarvenpaa, is an ESI founding member who was already present at our creation in 1999 in Sarajevo. She is also both a previous and future ESI senior analyst – but managed to squeeze in between time advising Martti Ahtisaari, Carl Bildt (in Bosnia), Michael Steiner (in Bosnia and Kosovo), the British ream preparing their Afghanistan operations and most recently UNAMA in Kabul. Few people know more about state building efforts in the past two decades than Minna does, having worked on the issue in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan.

This summer I was happy that Minna joined me – busy drafting the outlines of a book on the subject of intervention that I am writing together with my friend Rory Stewart – for a few days of brainstorming on the shores of the Bosporus. In the end we hardly left the cafes along the sahilyolu, the coastal road, in Rumeli Hisari as we tried to make sense of our various experiences. There and then we also refined ideas for a future ESI project on the subject with Minna back on board – how to learn some of the right lessons from the big interventions of the past 20 years relevant for the future EU foreign policy.

To participate in this exchange – in particular if you are unable to join us in Vienna later this week – please find below some thoughts which Minna prepared in anticipation of our panel.

MINNA JARVENPAA: INTERVENTIONS FROM BOSNIA TO AFGHANISTAN

Special contribution for Vienna Seminar, November 2010

The story from Bosnia to Afghanistan, over the last fifteen years, is of increasingly complex international interventions. The initial aims were simply to halt ethnic cleansing, remove abusive regimes and stop wars. But since the mid-90s the international community has struggled to build up state institutions and spread democracy and development in places like Afghanistan, Bosnia, Congo, East Timor, Iraq, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Somalia and Sudan. Now, with the Afghanistan strategy in a quagmire, questions are being raised about the limits of international power. Calls to avoid foreign entanglements are growing louder, and the pendulum has started swinging back to a more isolationist position.

Despite good intentions – seeking to safeguard human rights and promote state structures that will serve the populations in war-torn countries – the international community has often made things worse. But not intervening can in some cases also be disastrous, as the dismal failure to stop genocide in Rwanda and Srebrenica in the mid-1990s demonstrated. Future foreign policies will need to strike a delicate balance, weighing the morality of preserving human rights against the unintended consequences of intervention. How are we to navigate a course between disastrous inaction and misconceived and sometimes equally disastrous action? What are the moral and ethical guideposts to follow? What can the experiences of intervention and state-building over the past fifteen years, from Bosnia to Afghanistan, tell us about how to act in the future?

The era of intervention

When the bipolar world of the Cold War collapsed, the majority of nations found themselves in agreement on a set of universal human rights. Yet the end of the Cold War also meant the end of simple answers, a lack of order and predictability in international relations. Who was responsible for protecting the human rights we all now claimed to value? How were these rights to be enforced? There was a need for a new narrative. This is when the narrative of humanitarian intervention was born, as well as the idea that the international community could keep countries from descending back into violence and launch them onto a path of stability through some form of trusteeship – or through what has come to be called state-building.

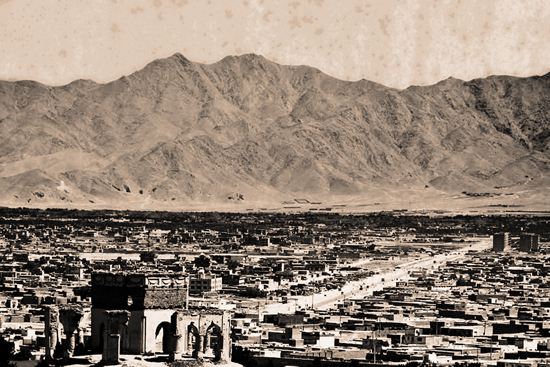

Some interventions in the 1990s succeeded beyond original expectations. After much hesitation in Washington and European capitals, the internationally brokered peace deal in Bosnia ended a brutal war, and the presence of international military forces restored a multi-ethnic democracy, without a single soldier being killed. In Kosovo, ethnic cleansing was reversed through a war that was fought solely from the air. In Afghanistan the original aim of toppling the Taliban regime was achieved within two months with small numbers of US special forces working together with the Northern Alliance, a loose union of Afghan commanders. In Sierra Leone, a limited British intervention led to the resumption of the peace process. These successes, coming after the paralysis in decision making in the face of genocides in Rwanda and Srebrenica, led to the articulation of a doctrine of humanitarian intervention: the ‘responsibility to protect’. It was morally imperative and practically possible to intervene.

Fixing failed states

However, because of the ease with which these interventions in Bosnia, Kosovo, Afghanistan and Sierra Leone fulfilled the original aim of ending war, it appeared to Western policy makers and thinkers that it was possible to do much more. There was a growing conviction that intervention should be followed by an all-inclusive state-building effort to transform the social, political and economic circumstances that had led to violent conflict. After 9/11 this view was reinforced. The fact that the Taliban government in Afghanistan had hosted Osama bin Laden was taken to suggest that failed and fragile states posed a direct threat to national and global security. To protect its own vital national security interests, the West needed to contend with state weakness far away from home

While ‘nation-building’ was initially mocked by the neo-conservatives in the US administration, an all-encompassing counter-insurgency doctrine that incorporated these ambitions was developed already under President Bush for Iraq and Afghanistan. The current strategy for Afghanistan, led by President Obama, requires tackling everything from building efficient institutions to upholding women’s rights to fighting the narcotics economy and supporting agriculture.

The rush to fix failed states has led to problematic ways of thinking about social change. It is assumed that countries are a tabula rasa where institutions can be built as a technical exercise on the basis of organisational charts and laws copied from other countries. Superficial lessons have been transferred across from one country to another. When Bosnians voted in nationalist parties in their first post-war elections, a general lesson was taken that the holding of elections should be delayed for some years after conflict. When the Kosovo Police School has hailed as a success the same curriculum was applied to Afghanistan. With General Petraeus at the helm, the military surge in Iraq is being replicated in Afghanistan, as is the search for tribal deals to turn the tide against the insurgency.

Even more worrying are the unintended consequences of deploying militaries and spending aid dollars that are also becoming increasingly apparent. In Iraq a brutal dictator has been removed at the cost of thousands upon thousands of civilian lives. Damaging war economies have developed around military deployments and aid flows, whereby Afghan, Congolese, Sudanese and other elites operate in a political marketplace where conflict is a lucrative business. To supply the NATO military bases in Afghanistan, trucking companies and private security contractors compete for patronage to gain access to multi-billion dollar contracts. Competition for access to foreign assistance projects and mineral resources fuels further conflict, as in the case of blood diamonds in Congo or inter-tribal skirmishes spurred by unequal shares in aid.

Lessons for future interventions?

As the international community stumbles along responding to crises, we have made some situations better and some much worse. Careful, prudent and limited missions to stop or contain conflict have worked, especially when carried out on the basis of political settlements or peace agreements. In other cases, with the best intentions, we have ended up supplying the resources that fuel the conflict, and have been manipulated by local power-holders who have pursued their own goals. Rather than focusing on the technical aspects of state-building, we would do well to increase our understanding of local politics. Democratisation is about power relations and about how the abuse of power can be prevented. Institutional reform can only take place if there is political will.

Instead of reaching for generic lessons, like those in “The Beginner’s Guide to Nation-Building”, published by the Rand Corporation in 2007, more time needs to be spent learning about the local context and thinking through the consequences of specific actions in that context. There is an argument that needs to be made for upholding democracy and human rights and containing conflicts, but with a realistic assessment of the opportunities and limits of international power.

An excellent succinct overview from an astute observer. I can only assume world leaders read this in timely fashion before deciding on the strategy to be adopted in Libya. It will be interesting to see what unravels in Bahrain, Yemen, Syria in terms of the nature of the international response (if there’s one at all).