A disclosure at the very outset: since 2000 Swedish governments have been among ESI’s most faithful supporters.

This is hardly a coincidence. On every foreign policy issue important to us Sweden is a strong advocate within the EU, from support for EU enlargement to the Balkans and Turkey to a European perspective for countries in the Eastern neighbourhood. Being one of the wealthiest member states, having a good record of implementing European legislation, and not being suspected of having a secret agenda of undermining the European project, adds to its credibility.

What would it take for EU-ropeans, old and new, social-democrat, liberal and conservative, to embrace the Swedish outlook on Europe’s future? To share the vision one finds in the speeches of Sweden’s current foreign minister, Carl Bildt, for instance in his presentation delivered in 2007 in Bruges at the College of Europe:

“In Maastricht in 1991, the then European Community decided to transform itself into a more ambitious European Union, and soon this Union was prepared to open up not only to old former ‘neutrals’ like Austria, Finland and Sweden but also – and far more important – to all the countries of Central Europe, the Baltic region and down towards the Black Sea.

There is no doubt that it was the magnetism of the Union and the model it provided that made the transformation we have since seen in all of these countries possible. When – at some time in the future – the history of the Union is written, this might well be seen as truly its finest hour.

Today, we see 10 nations with some 100 million people from the Gulf of Finland in the north down towards the Bosporus in the south creating a new belt of lasting peace, stable democracies and bubbling prosperity in an area that history had otherwise reserved for instability, conflicts and great power rivalry.

Our Union today is a union of approximately 500 million people. It is the largest integrated economy in the world. It is by far the largest trading power of the planet – larger than the second and third put together. It is the biggest market for more than 130 nations around the world. It provides more than 60 per cent of all ODA to the developing countries. And – remarkable as it sounds – the value of the euros in circulation on global markets exceeds the value of dollars.

We certainly have our problems – but we should not overlook the weight and importance that we have in the global economy. Others do not.”

And then Bildt continues:

“What is needed is a profound strengthening of the soft power of Europe. We certainly need to strengthen the hard power as well – but at the end of the day peace is built by thoughts and by ballots more than by tanks and by bullets.

A critical part of the soft power of Europe lies in the continued process of enlargement – a Europe that remains open to those in our part of the world who wish to share their sovereignty with us, accept the rule of law and commit themselves to the building of open, secular and free societies.

There are those who want to slow down or perhaps even stop the process altogether. We have heard talk of the need to define the borders of Europe. And to draw these borders as close to the present borders of the European Union as possible. But drawing big lines on big maps of eastern Europe risks being a dangerous exercise for us all.

Because it means defining firmly not only for whom the doors will remain open, but also slamming the doors in the face of some for whom the magnetism of Europe remains a major driving force for profound political and economic reforms. It means telling them to go elsewhere. And that means doing things differently also in terms of the evolution of their societies. If we put out the light of European integration in the east or southeast of Europe – however faint or distant that light might be – we risk seeing the forces of atavistic nationalism or submission to other masters taking over. And if that happens, no lines on maps will be able to protect us from the consequences.”

At a recent ECFR meeting in Stockholm Carl Bildt reiterated these positions, striking a positive tone that stood in marked contrast to the pessimism about Europe’s future I noticed among many of the other ECFR members.

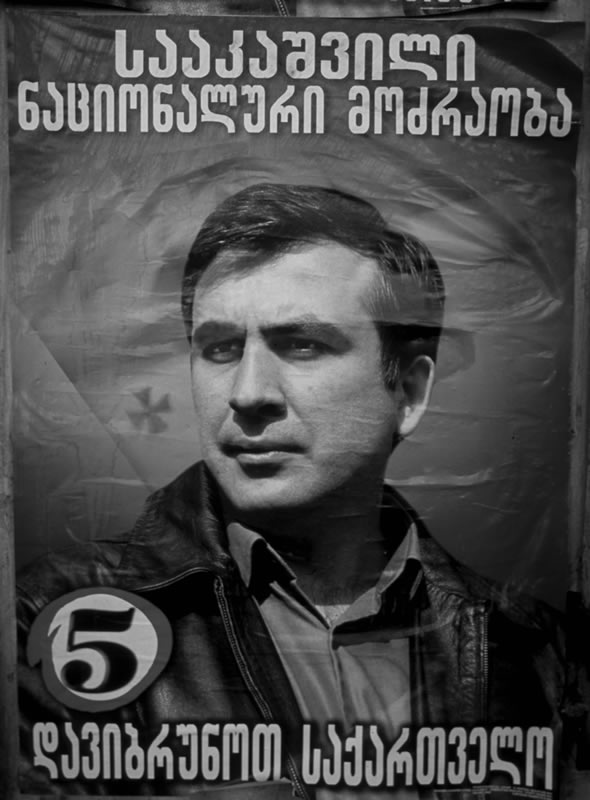

Strikingly, in Sweden support for enlargement is not controversial. Swedes of all political families believe that European values can be shared by Turks and Moldavians, Ukrainians and Georgians, to the benefit of all of Europe. As Goran Lennmarker, chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Riskdag (parliament), told me just this week, the Swedish consensus today is that when any European country meets the conditions for accession, it has a right to be accepted as a member.

Public opinion is also supportive and so far the Swedish political elite have decided not to strike a populist tune on enlargement. 63 percent of Swedes argue that enlargement has strengthened the EU: this is the highest support among the 15 ‘old’ member states, where an outright majority for this view exists only in Spain (59 percent), Denmark (53 percent) and Greece (53 percent). A clear majority of Swedes is in favour of the integration of each of the Western Balkan states (see below the Spring 2008 Eurobarometer results).

|

SWEDISH ATTITUDES TO FURTHER ENLARGEMENT (Eurobarometer):

|

|

Spring 2008

|

Alb

|

BiH

|

Cro

|

Kos

|

Mac

|

Mon

|

Ser

|

Tur

|

|

For

|

58

|

66

|

71

|

61

|

66

|

66

|

61

|

46

|

|

Against

|

32

|

25

|

20

|

29

|

24

|

24

|

30

|

45

|

|

Undecided

|

10

|

9

|

9

|

10

|

10

|

10

|

9

|

9

|

Some years ago, the Swedish parliament passed a resolution offering Moldova, Ukraine and Belarus a European perspective (provided, of course, that they meet the Copenhagen criteria).

All of this raises interesting questions: why is a position that seems mere common sense in Stockholm so controversial in Paris and Berlin? Namely, that previous enlargements have made the EU stronger, and that future enlargements – as long as they are carried out cautiously – will do so as well?

Of course, some might say, Sweden is doing particularly well. This is true. Until the current economic crisis unemployment was low (it is now rising fast, however, to almost 8 percent in the first quarter of 2009). The country ranks among the 10 richest countries in the world in terms of per capita GDP. Combining GDP per capita with indicators for eduction, literacy and life expectancy, Sweden came 7th worldwide in the latest Human Development Index published in December 2008. Sweden’s economy is highly competitive: in international surveys of competitiveness, Sweden excels, coming 4th in the World Economic Forum competitiveness ranking 2008/2009, just behind the US, Switzerland and Denmark.

Perhaps one reason for the strong consensus in favour of EU enlargement is a general confidence in the Swedish model of balancing freedom and security? Perhaps Swedes are more prepared to take risks, since failure is not so disastrous, for individuals and for groups in society? According to this logic it becomes easier to embrace EU enlargement against the background of a public commitment to social welfare. This promises that within society burdens are shared, so the benefits of enlargement do not accrue only to a few social groups. A domestic welfare bargain appears to underpin support for an outward looking EU: relatively low levels of income inequality, and comparatively high per capita income taxes (in 2006 Swedish wage taxes were the second highest in the world, behind Denmark: see here).

Confidence in the future is also expressed in one of the most striking recent policy innovations: a reform of the rules for labour migration, adopted by parliament in December 2008. As a result of this reform, a Swedish employer is now the one to decide whether a given non-EU foreign worker is needed for hire (before these reforms the Swedish Public Employment Service decided this; for more details go to the website of the Swedish Migration Board). This is implemented in a country in which 12 percent of residents are born abroad.

How about gender policies? It is certainly interesting that the country with the strongest commitment to European soft power is also the one with the largest number of women in positions of political authority: in the most recent survey by the IPU on women in national parliaments, Sweden comes out second in the world, just edged out by Rwanda. Or is having low rates of corruption a key to a shared belief in soft power in foreign policy? In the 2008 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index Sweden comes 2nd in the world, only beaten by Denmark.

Transparency in policy making might also help support a pragmatic EU policy. Sweden is famously transparent in its public administration, making it perhaps harder for theories of elite conspiracies (“enlargement is a capitalist plot”) to gain ground. Sweden’s freedom of information policies ensure that all external communications with ministers and state secretaries are made public. In principle all items of mail to the government and government offices are public documents, something that has led to clashes between Sweden and the rest of the EU (see here for one example).

Are people who are satisfied with their lives more likely to be open to others? Swedes score well in international happiness indicators: in one table based on the 2005 World Values Survey Sweden also comes in 2nd place. (Behind Iceland, which was probably before its economy crashed! Let me admit, though, that I am not all confident about international “happiness rankings”, with Bangladesh coming out on top in one global happiness survey, and Nigeria in first place in another).

And then there is the structure of the Swedish economy: its openness to the world economy, the large number of Swedish multinationals, traditional support for free trade policies. Sweden’s relatively small population (9 million) lives in Europe’s fourth largest country in terms of land mass; its economy has historically been dependent on export: first of its raw materials, then its industrial goods and finally its ideas, to world markets.

But neither wealth nor exposure to international trade alone explain the strong commitment to globalisation and EU enlargement: otherwise Switzerland, Austria or the Netherlands would have adopted foreign policies similar to Sweden (the contrast with Austria attitudes, when it comes to Turkish accession, is particularly dramatic).

What then are the intellectual and emotional roots of the Swedish approach to foreign policy? And what would a more Swedish EU foreign policy look like?

To answer these questions, I suggest to turning away for a moment from international league tables; and to pick up a very different set of books and travel to a special region south of Stockholm to understand the paradox of the Stockholm consensus on enlargement and the Swedish approach to politics. But more on this later.

Recommended, if you want to know more about Sweden: Previous blog entry: Silences and the new Sweden. For Jon Stewart’s take on the Swedish model, please go here. It is hilarious and, as always with Stewart, enlightening. Of course, the country The Daily Show presents is too good to be true … a place without conflict, full of attractive and reasonable people …

To counterbalance (somewhat) this approach let me note that there is of course no shortage of critical Swedes who argue that, for all of its comparative successes, Sweden constantly needs further reforms to remain competitive. Some of these critics can be found in Timbro, a free-market think-tank, which has challenged what it perceived as “Suedo-sclerosis” since its foundation in 1978. There you also find an interesting report by economist Mauricio Rojas, Sweden after the Swedish Model – from Tutorial State to Enabling State, which tells “the story of the rise and fall of the old Swedish model” and the transition to what Rojas calls the current Swedish “enabling state”.

In Stockholm this week I also had a long conversation with one of the most articulate and influential representatives of this view, Peter Egardt – Carl Bildt’s former state secretary (in the early 1990s) and now president and CEO of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce, member of the national bank, and long-time board member of Timbro (1995-2005). As Egardt put it in an article on how to attract the “creative class” to Swedish cities:

“Abroad, many believe Sweden to be the very showcase for social democratic welfare states. However, ambitious reforms implemented during the past few decades have transformed Sweden into a competitive economy with an increasing degree of economic freedom and strong growth. In the wake of this development, culture, fine food and the arts have all blossomed in Swedish cities. Tourists, as well as businesses, are attracted not least to the capital city of Stockholm. The strategy underlying this development has been based on a sound business-and-growth-friendly policy orientation, not a Berlin style emphasis on public subsidies of culture over families and businesses. Cultural development has occurred as the result of a growing economy, not the opposite.”

For another outsider’s view how in Sweden “high per capita income and open markets go hand in hand with social cohesion” read the latest OECD Report (2008). There is also a lot of information and background reading on Sweden on the website of the Swedish institute: www.si.se.

Finally, let me note that Mark Leonard, the current director of ECFR, first used the concept of a “Stockholm consensus” in his book “Why Europe will run the 21st Century”:

“The Stockholm consensus amounts to nothing less than a new social contract in which a strong and flexible state underpins an innovative, open, knowledge economy. This contract means that the state provides the resources for educating its citizens, treating their illnesses, providing childcare so they can work, and integration lessons for newcomers. In exchange, citizens take training, are more flexible, and newcomers integrate themselves.”