Ouroboros – the snake that devours itself

If you come to our website often you will have noticed that ESI writes a lot about the Council of Europe. You might wonder why. Are there no other, more important European issues? And why is our stance so critical?

One reason that we keep returning to issue relating to the Council of Europe is that almost nobody else does, outside of a small group of human rights activists mainly concerned about the crackdown on civil society in Azerbaijan.

For large European think tanks and for most European media, the crisis in the Council of Europe still does not exist. Or does not really matter. Why care about debates in PACE, or about what the secretariat in Strasburg does or does not do, when there is a war in Ukraine, crises in the Middle East and challenges to democracy in old and new EU members?

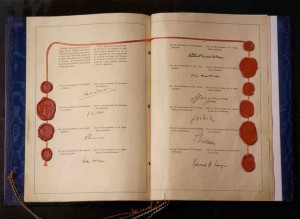

We at ESI disagree. We believe that when the institution that gave us today’s European flag, and that remains the guardian of the moral constitution of democratic Europe – the European Convention on Human Rights – is fatally undermined, this points to a very serious crisis for all of Europe. It is a wound that must not be allowed to fester. Today the Council of Europe resembles Ouroboros, the snake of Greek mythology that devours itself … in this case, by destroying the moral basis on which it was founded.

Look at the European order today, and Europe’s big three organisations: the OSCE, the EU and the Council of Europe.

The OSCE has a justification as a forum for debate even with autocracies. This was its original conception in Helsinki in 1975. This is why Belarus (and Uzbekistan and the Vatican) can be members today.

The EU has to defend its own standards internally (and do a much better job at this) and externally, in particular when it comes to its ongoing enlargement talks.

For the Council of Europe, however – the first institution to enlarge to almost all of Europe in the 1990s – the current crisis of values, norms and credibility is existential. It has to be a club of European democracies, or it does not have any reason to exist.

This is why Belarus is not a member today. This is why Russia and Azerbaijan currently have no place as members, unless things change in both countries. There really is no use for an institution focusing on human rights and democracy when these standards are defined by autocracies and thus undermined for everyone else.

ESI strongly believes that the Council of Europe should matter. It should be talked about more. It should be given the resources to fulfil its crucial role better. But the key recource missing today is not money, but attention. Think tanks and media should follow what happens in Strasburg. It is a shame that the foreign ministers of influential countries attend its meetings so rarely (to begin with Germany and France) and that parliaments throughout Europe pay so little attention.

We believe that it is important to preserve the idea that one day the European Convention on Human Rights will be the normative basis for all of Europe (including Russia and the South Caucasus), not just the current European Union. Just as it was crucial to preserve this aspiration in the decades prior to 1989 in a divided Europe. It may look unlikely now; it definitely looked implausible then.

For what is the European Convention? It is the basis of civilised life, in a continent known as much for autocracy and human rights violations as it is known for the enlightenment and rights.

It is comprised of the following basic commitments, that are once again under pressure across the continent:

Article 1 Respecting the rights in this convention

Article 2 The right to life – a duty to refrain from unlawful killing and to investigate suspicious deaths

Article 3 Prohibits torture, and “inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment”. There are no exceptions on this right.

Article 4 Prohibits slavery, servitude and forced labour

Article 5 Provides the right to liberty, subject only to lawful arrest

Article 6 Provides a detailed right to a fair trial

Article 7 Prohibits retroactive criminalisation

Article 8 Provides a right to respect for one’s “private and family life, home and correspondence”, subject to certain restrictions “necessary in a democratic society”.

Article 9 Provides a right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Article 10 Provides the right to freedom of expression, subject to certain restrictions “necessary in a democratic society”.

Article 11 Protects the right to freedom of assembly and association.

It is irresponsible to close our eyes to the fact that today the European Convention is being mocked by certain member states of the Council of Europe, not occasionally but systematically. Today these core articles are not only disregarded but also openly challenged.

If Azerbaijan or Russia were expelled from the Council of Europe today (or would preemtively leave voluntarily) then this does not mean that a democratic Azerbaijan or Russia might not one day join again. In fact, that would be the goal. It would give human rights defenders in these countries a clear objective. And they should be supported in this in all possible ways. Greece was not in the Council of Europe under military rule in 1968 … and later rejoined it as a democracy.

Today we have the worst of all worlds. We see the standards of the European Convention on Human Rights mocked, the institution and its bodies paralysed. We see these institutions turned against the very people in those countries who defend them there … and who risk jail and worse for doing so.

We see democrats indifferent to the institution, while autocrats invest resources to capture and manipulate this critical intervention. Things are upside down. It is time to put them back in order.

We have written before about parallels between the fate of the League of Nations and what is currently happening in Strasburg (See : Europe’s Abyssinian Moment).

Here is another thought-provoking parallel from Europe’s early 20th century history. At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference East European nations signed treaties guaranteeing rights to minorities. These treaties called for religious freedom and civic equality. Minorities were granted the right of petition to the League. Governments in Eastern Europe complained about these “unjust requirements that the great powers did not impose on themselves”. These countries had a point. However, the proper response to this complaint was not to water down these rights, but to apply them equally to everyone.

Instead, the solution chosen was the worst of all. These rights were never applied and these treaties were never taken seriously. Despite there being a special League of Nations Minorities section it proved to be a “weak reed”: of 883 petitions the League received between 1920 and 1939, only four resulted in condemnation of the accused state. When the first anti-Jewish university quota system was introduced in Hungary in 1920 protests at the League of Nations failed to secure the law’s withdrawal. (For more on this see Bernard Wasserstein’s fascinating book “On the Eve – the Jews of Europe before the Second World War.)

Perhaps then too there were serious and influential people who thought that Europe had more important problems than to defend norms and treaties concerning human rights in small East European nations.

However, this assumption was wrong then and it is wrong now. The crisis in Strasburg matters not just to a few brave human rights defenders on the European periphery. It matters to all of us.

This contradiction matters

PS: For more on the crisis of the Council of Europe, see also the latest ESI newsletter:

- The mercy of Commodus – The failure of Jagland (14 November 2014)

- Oslo – The dream of a Europe without political prisoners and the grim reality of Azerbaijan (12 November 2014)

- Standing up for European values